[SOUND OF ENTERING PRESCHOOL]

AUBRI JUHASZ, HOST: Union City, New Jersey is right across the river from Manhattan, just a short drive from Times Square. It’s a dense city with a lot of recent immigrants, all hoping for their shot at the American dream. And education is a big part of that.

The schools here used to have a really bad reputation. For a while, Union City’s school district was on the verge of a state takeover, because its test scores were so low.

SILVIA ABBATO: At one point I remember going to workshops and they would say, ‘Where are you from? And I’d say Union City. And they’d say, ‘Oh, the Dirty 30.’ That’s what we were referred to, as the Dirty 30.

AJ: Why were they calling you that?

SA: Because we were considered not high achieving districts at that time. And that’s an awful thing because you’re working with less funding than suburban districts had, and it wasn’t the fault of the staff. It wasn’t the fault of the administration. It wasn’t the fault of the children. It’s just that the money wasn’t there, and there wasn’t that commitment from the state.

AJ: That’s Silvia Abbato, a long-time educator here who is now the district’s superintendent.

And the expression Dirty 30 had another meaning.

[MUSIC]

It referred to the roughly thirty poor urban school districts in New Jersey that were part of an ongoing lawsuit against the state for more school funding. The case closely mirrors Pennsylvania’s recent case. And, spoiler alert, that’s why we’re here.

SA: Now it’s like, ‘Oh my God, you’re doing such wonderful things.’

AJ: So what happened?

New Jersey eventually gave Union City and the other poor, urban districts in the state a lot more money. And while the road from bad to good to great was bumpy, educators and politicians here capitalized on the opportunity, spent the money wisely, and ultimately pulled off a dramatic turnaround.

SA: It is very heartwarming and wonderful when you get that response because we came in from the bottom and now we’re at the top and keeping it at the top, which is key.

AJ: Many students in Union City don’t speak English at home. A good number are recent immigrants. And a lot of them live in poverty.

SA: Some of the challenges that our students face are huge and the educational system more than makes up for it.

AJ: That’s something you almost never hear.

SA: So you don’t expect these children to be as successful, which is a terrible thing to actually say. But because of the school system and the community and the support from the community, they make it.

AJ: And many do more than just make it.

Not only is the district’s graduation rate on par with the rest of the state, a lot of students go on to earn college diplomas, some from the most competitive colleges and universities in the country.

[THEME MUSIC]

SA: There’s a way out of poverty, and it’s called education.

AJ: From WHYY, this is Schooled, a podcast where we tell the story of public schools through the eyes of students, parents, and teachers. I’m Aubri Juhasz.

In this episode: a look at the changes in school funding that transformed public schools in New Jersey and what it could mean for Pennsylvania.

Then, a visit to Pennsylvania’s capitol to see how legislators are responding to the court ruling that says the current system is unconstitutional.

And, how underfunded schools are taking matters into their own hands while they wait for help from the state.

That’s coming up, on Schooled.

[MIDROLL BREAK]

Silvia and her twin sister Adriana Birne are deeply committed to Union City’s schools. They grew up here, and they’ve spent their entire careers in the district. At this point, more than 40 years each.

Like many of their students, they were immigrants and didn’t speak any English when they started. Here’s Sylvia:

SA: When we came from Cuba, we were nine. And I remember sitting in the classroom and I was a top-performing student in my school. I recited poems in kindergarten, And they put us all in a class, and now you have a teacher doing the vowels, ‘A, A. E, E. I.’ You’re in fourth grade. I was bored.

AJ: Things have gotten better since then.

[MUSIC]

Today, the district offers comprehensive bilingual education, including a gifted program. Students who come in not speaking English learn in both languages so they don’t fall behind in their coursework. And once they’re fluent, they move into English-only classrooms.

How many years has it been since you guys started working in the school district?

SA: A lot.

AJ: Back then, the district’s school buildings were in disrepair. Silvia tried to hide it from visitors.

SA: I remember I had holes in my wall and I put posters, pretty posters. So when they came in, there were no holes in the wall. But those are the things that you did because you didn’t have the facilities.

AJ: It was issues like these that inspired a school funding lawsuit in New Jersey, very similar to the one Pennsylvania just went through. It was called Abbott v. Burke, and it was filed in the 1980s.

[SOUND OF NEWSCAST ABOUT ABBOTT BEING FILED]

The case didn’t result in instantaneous change, and the long-term results aren’t perfect. But with time and many returns to the court over the course of decades, more funding started to flow to schools that were in need.

And with that, Union City and the other districts won big time.

New Jersey’s Supreme Court said poor urban districts had to receive the same resources the affluent suburbs had. Not only did the state have to send these districts a lot more money, it also had to cover 100 percent of their construction costs.

And to make sure the children in poor urban districts had every opportunity to succeed, the court also forced the state to pay for another thing — two years of full-day, high-quality preschool.

SA: They leave kindergarten classes reading and writing, which was unheard of before preschool education was a mandate in New Jersey.

AJ: Silvia’s sister Adriana is the director of early education for the district, and the two of them gave us a tour of Union City’s early education center to see preschool in action.

[SOUND OF PRESCHOOL HALLWAY]

The building has classrooms with the latest technology, an aquarium in the lobby, and elaborate decorations.

ADRIANA BIRNE: The magic here is that we have trees all decorated.

AJ: There are life-size trees and flowers made out of craft paper that make the hallways feel like Disney World.

You’ve got some talented teachers who are very artistic.

AB: Oh, they are. But they receive a lot of professional development.

AJ: The decorations aren’t just fun. They demonstrate the high standard of learning that’s taking place. There are projects that show off their 3 and 4-year-olds’ handwriting and critical thinking.

AB: And again, we’re treating the little ones just like you would in any other grade. You have claims, rejections, evidence, introducing…

SA: The scientific method.

AJ: And Silvia is always looking for ways to expand what students are learning.

[SOUND OF KIDS SINGING ALONG IN MANDARIN]

SA: I did a little research and I found that the suburbs teach Mandarin in their classrooms. So guess what? In Union City, we have Mandarin classes in two of our schools. So the little ones will leave early childhood speaking Spanish from their home. English from the schools. And Mandarin. How beautiful is that? And why not?

[SOUND OF TEACHER REPEATING MANDARIN VOCABULARY WITH KIDS]

After that, we pop into another classroom.

AB: Good morning boys and girls.

CHILDREN: Good morning.

AB: I have friends here that would like to see your classroom. And perhaps maybe ask you a question or two.

[SOUND OF PRESCHOOLER TALKING ABOUT CONSTRUCTION]

[MUSIC]

AJ: The high-quality early learning that’s happening here — it’s possible because of that court case in the ‘80s that eventually changed school funding in New Jersey.

STEVE BARNETT: It’s resulted in what really is in many ways the best preschool program on the planet.

AJ: That’s Steve Barnett. He’s an early education researcher who served as an expert witness in both New Jersey’s and Pennsylvania’s school funding cases. Steve says New Jersey’s preschool program is a model not just for the nation, but the world.

SB: The city council from Oslo, Norway, came to New Brunswick, New Jersey to learn about educating immigrant kids.

AJ: He says the success of New Jersey’s preschool program goes back to how the program was designed.

SB: Often it’s because the standard operating procedure is to begin with the budget and work your way backward.

AJ: But this was the other way around. Mandated by the court, the state handed the reins to early education experts to design a program without worrying about the price tag. That meant they could actually implement research-based practices. They capped classes at 15 students, each with a lead teacher and an assistant.

School districts didn’t have the capacity to create preschools out of thin air. So they partnered with programs that already existed, that were willing to rise to the state’s high standards. And for the most part, they did.

To this day, in the rest of the country, all of this is still pretty much unheard of. Even though the benefits of high-quality preschool are well known.

SB: I don’t understand why any state would not want to invest in early childhood to make sure kids don’t enter the kindergarten door a year or two years behind. Why play catch up?

AJ: But again, it was a bumpy road toward success in New Jersey following its school funding trial. And nobody knows that better than David Sciarra.

He was the lead attorney for the plaintiffs — 20 school children — in the case Abbott v. Burke. And went before New Jersey’s Supreme Court over and over again to make sure the state paid up.

DAVID SCIARRA: Well, we’re up to 23.

AJ: That’s 23 orders from the state Supreme Court over more than three decades. David has a few key takeaways from this lengthy experience.

DS: One of the important messages we were always trying to make was that this was not going to be a Robin Hood situation.

AJ: Meaning, the goal wasn’t to redistribute resources from wealthy to poor districts. They weren’t gonna pool all the money from local property taxes and divide it up.

DS: This was essentially lifting up the poor districts to what they needed. It wasn’t going to be winners and losers.

[MUSIC]

AJ: The problem was, and still is, that pumping more state money into the system to help poorer districts catch up doesn’t address the underlying issue — relying on local property taxes to help fund schools.

In New Jersey, just like in Pennsylvania, there’s a lot of economic inequality between school districts. Some are really wealthy and others aren’t. That means property taxes are an inherently inequitable way to pay for schools.

ZAHAVA STADLER: It happens to be that New Jersey compensates for that really hard with very high levels of state investment, and it’s still not catching up.

AJ: Zahava Stadler works for the public policy think tank New America, where she studies equity in school funding.

While the money awarded to poor urban school districts brought spending up to the level of suburban schools, and in some cases beyond, those increases haven’t been sustained. And as a result, the gaps between high- and low-wealth districts have opened back up.

Zahava says Pennsylvania doesn’t want to find itself in the same position.

ZS: The ground-level inequalities are too big for states to constantly try to fix them only by pouring state money into the hole. That money is going to run out. And when states hit recessions, the districts that are most at risk are the highest poverty, lowest wealth districts that depend most on state help. And so that means that the system is set up to fail the neediest in hard times.

AJ: So what’s the solution?

ZS: There’s no law of nature that says it has to be this way.

AJ: We’ve traditionally relied on local property taxes to fund schools as a country, but Zahava says we don’t have to.

ZS: Ultimately, this is all a policy choice and it’s a policy choice that state legislators are making or a policy choice that state legislators are declining to make.

AJ: And some states have decided to do things differently.

Like Vermont, which has a more Robin Hood-like situation where wealthier towns pay higher property tax rates to subsidize schools in poorer areas. And Kansas, where the state caps how much districts can spend, preventing gaps from forming in the first place.

Pennsylvania and New Jersey don’t do that.

Meanwhile, Zahava says in both states, the wealthier suburbs are moving the goalposts for everyone.

ZS: They have changed the definition of how much is enough for my education because we’re applying for the same state university spots, we’re applying to the same jobs on graduation. So there’s no such thing as, ‘How much is enough?’ And then, ‘Hey, if the other guy wants to raise more money, that’s up to them.’ Ultimately, they’re redefining enough for all of us because we occupy the same society.

AJ: David Sciarra, the lawyer in New Jersey, says he knew that asking the state to fill an ever-growing gap wasn’t the best solution, but it was the one they had based on the court’s ruling. And it was hard enough getting elected officials to go along with it.

DS: We all always want a quick fix. Have test scores gone up from one year to the next? It’s the wrong question. The question is, ‘Is the state leading the effort to make progress over time from year to year, from even decade to decade?’

AJ: While the money from New Jersey’s court decisions has led to transformational changes in Union City, that hasn’t been the case for all of the plaintiff districts. Some have shown more modest progress, while others haven’t shown very much progress at all.

Overall, New Jersey has some of the highest test scores in the country today, and some credit the Abbott funding for that, but there are still large achievement gaps between children based on race and income.

DS: So what does that say? It doesn’t say that we shouldn’t do it. The kids are entitled to it. The state has an obligation to provide it.

AJ: For example, before Abbott, some public schools in Camden, New Jersey didn’t have cafeterias or up-to-date textbooks. They have those things now — plus more teachers, counselors, and social workers to help children who are struggling.

DS: I think overall it’s a tremendous advance for kids.

AJ: This shows it takes more than just money to move the needle.

[MUSIC]

You need political support — Union City’s mayor is a champion for its schools — and committed school leadership, like Silvia and Adriana.

SA: I always like to be ahead of the game.

AJ: The district is known for its continuous improvement model. It’s constantly adapting, and teachers get regular feedback.

SA: You always want to get better. You just don’t want to be stagnant. I think that’s our key.

AJ: Silvia has her eyes on two things. How is her student body changing, and what do they need? She also keeps tabs on what’s happening in the suburbs, because she wants her schools to have the same things.

You can see this at the district’s new STEM high school.

[HIGH SCHOOL TOUR MONTAGE]

Students have been recognized for their research, which Silvia says gives them an important edge when they apply for college. Like one student who’s working with NASA to confirm that he discovered an exoplanet.

So while money isn’t everything, none of this would be possible without it. And Silvia knows that.

SA: You always have to worry about money.

AJ: Because from one governor and one legislature to the next, nothing is certain. Without changing the property tax system, gaps can always reopen.

But what is certain in Union City is Silvia and Adriana’s commitment.

SA: We’re not going anywhere. We care about the community. We care. We built this foundation, and we want to see it through.

AJ: So what can Pennsylvania learn from all this? With a recent court decision potentially changing how public schools are funded, what’s next? That’s coming up, on Schooled.

[MIDROLL BREAK]

[MUSIC]

I’m Aubri Juhasz, and this is Schooled.

The lawyer David Sciarra says the state of Pennsylvania can learn a lot from the success stories of New Jersey public schools.

DS: We know how to fix these things. Right? So it’s not like we don’t know the technical know-how. It’s a question of political willingness.

AJ: David says Pennsylvania’s Governor, Democrat Josh Shapiro, needs to think outside of the box. Look beyond one budget to the next. What’s the long-term game plan to fully fund all schools? If he doesn’t, then it might take more trips to the court, more decades, and more generations of students, for the recent ruling to become a reality.

DS: He has to step up. He’s got to get schooled on this court ruling and what it means and the opportunities that it creates for short-term and long-term change. And if he doesn’t lead it, this opportunity is going to be lost.

AJ: Governor Shapiro promised a ‘significant down payment’ for schools in his first budget address of the year.

[SOUND OF GOVERNOR SHAPIRO GIVING A SPEECH]

But the actual numbers left some people disappointed.

Funding advocates say the governor’s proposed increases just keep up with inflation. And they balked at his decision not to increase the amount of money sent to the state’s 100 poorest school districts.

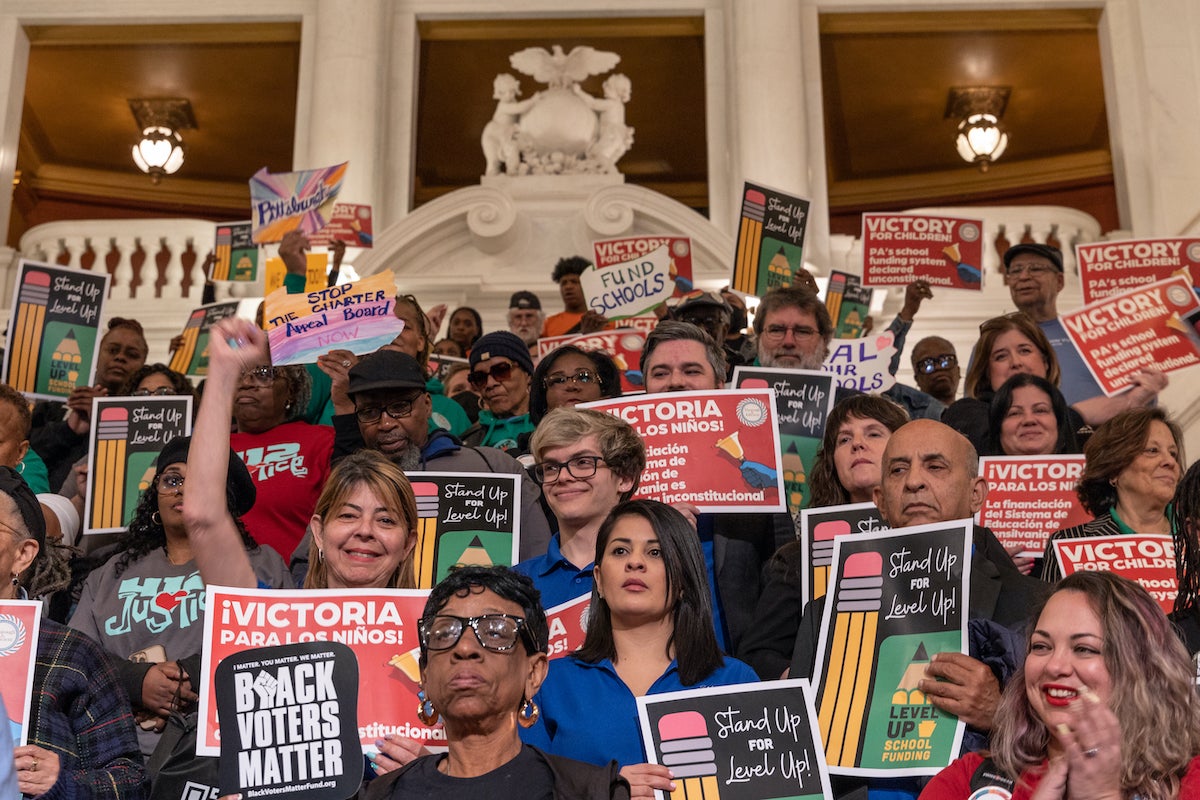

[SOUND OF CHANTING AT RALLY IN HARRISBURG]

So they converged on the Pennsylvania state capitol in late April to make their demands known.

[SOUND OF SPEECHES]

GINA CURRY: How many times have people come up here, been on the steps, given their testimony? How many meetings do we have to say this is what we’re going through? And to not be able to deliver because somebody doesn’t get it is very frustrating.

AJ: At the capitol, we met with Democratic State Representative Gina Curry.

[MUSIC]

Before she was elected to the legislature a year and a half ago, Gina was a school board member in Upper Darby, another property-poor school district right next to William Penn. She represents both districts in the state House.

Back then, she would come to the capitol every few months to meet with lawmakers and ask them for more money. Now, she’s the lawmaker who’s getting asked.

GC: It’s a part of when you come into the job, people are going to think you’re not doing anything.

AJ: Gina gets it. Before she was elected to the House, she sometimes felt the same way. But she insists she’s trying. The problem is the political process is overwhelmingly slow, and divisions run deep in Harrisburg. When we spoke with her, she sounded tired.

GC: I just don’t think everybody is in agreement that what’s happening is really happening.

AJ: Since the court ruling, the conversation has shifted. Most people know the system has to change. But Gina says that’s not enough to get everyone on the same page. How can you get people to understand — and care — that while some schools are able to raise enough money locally, others are struggling to make ends meet?

GC: There’s never going to be real kumbaya moments for situations like education because everybody has their own opinion about how it impacts their community.

AJ: Speaking at a recent event, Governor Shapiro was more optimistic. He expects bipartisan support on a solution that gets more money to low-income schools.

JOSH SHAPIRO: What we now need to do is come up with a formula that drives dollars out where the need is and increases the pot of dollars that go to those schools.

[MUSIC]

AJ: That pot is state money and it’s an important part of school funding, especially for property-poor districts that have a hard time raising money locally.

Most states use formulas to drive these dollars out to schools based on how many students they enroll. And Pennsylvania has a pretty good formula already. It takes into account the amount of money districts are able to raise locally, and the fact that some kids are more expensive to teach.

The glaring issue, though, is that the state doesn’t really use its formula. Because when it was passed in 2016, lawmakers decided to only apply it to new dollars.

Here’s policy analyst Zahava Stadler again.

ZS: All the state can do is really put some nice new icing on top of the existing unequal cake. Ultimately, when you bake in all the preexisting inequality, there’s not a lot of room to work.

AJ: For example, next year about a quarter of the state’s basic education funding is expected to be distributed using the formula. That means the vast majority of funding isn’t distributed based on current needs, but instead on decades of politics.

Shapiro says his goal is to revise the formula in time for the state’s next budget cycle a year from now. At this point, it isn’t clear how realistic that goal even is.

There are legislators who say they are for more equitable school funding but don’t make good on that promise when it’s time to vote on policies — because they’re afraid their schools may lose money.

JESSE TOPPER: Well, the reason that fear is there is because it’s justified. That is the current system.

AJ: Representative Jesse Topper is the Republican chair of the House Education Committee.

When we asked to speak with one of the Republicans named in the lawsuit, House GOP leader Bryan Cutler, he declined and told us to speak to Jesse instead.

JT: I think what Republicans and Democrats can agree on is that access to a high-quality education should not depend on your zip code.

AJ: Jesse says what Pennsylvania needs to do is set a funding baseline to make sure schools have what they need. And if a district wants to go beyond that, it’s up to them.

JT: In the world of education, there will always be the haves and have-nots in terms of who has the Olympic-sized swimming facility, who has, you know, the Taj Mahal basketball arena. And that’s fine. I’m okay with the local tax base determining those kinds of things.

[MUSIC]

AJ: It’s okay with him if students don’t have access to the exact same things, as long as a baseline is met. Because he says life isn’t fair.

JT: It’s the important lesson that my dad always taught me, which, whenever I said something wasn’t fair, he said, ‘Son, the fair comes once a year, and it’s not today.’

AJ: Gina says that stings because she lives in a community where things really aren’t fair.

GC: We’ve already lost, and we’re at the start with everybody else. Until we can get prepared, boosted up, ready for the race? We’re going to come in last.

AJ: This is personal for Gina. Her daughter is starting eighth grade next year in Upper Darby, a diverse part of Delaware County with a large number of recent immigrants.

HC: I’m just really trying to figure it out for her for the rest of the time. I want her so badly to be able to get through it. You’re gonna make me emotional.

AJ: For Gina, the fight for school funding is a family business. While she works on it in Harrisburg, a hundred miles east, her husband Rap Curry is dealing with the issue directly as the athletic director for the William Penn School District. He was a key witness for the plaintiffs in the trial.

RAP CURRY: Good to see you. Rap Curry.

AJ: The kids call him Coach, Coach Rap. It’s a throwback to his days as a student at Penn Wood in the late 1980s, when he was a star basketball player.

RC: We might as well walk around, take a look. Make sure I got my keys, since we’ll be walking.

AJ: Coach Rap has worked at the high school for more than two decades. He brings us around the back of the building to see the track.

[SOUND OF GRAVEL CRUNCHING]

RC: So this is gravel. It’s kind of like what the old days, might would have been like at a playground and you might have put it like where swing sets used to be.

AJ: It’s loose gravel. Not the rubbery turf you see at most other tracks.

RC: We can’t really play where we’ve been playing. And so we work really hard to, I use a concept called, ‘Do more with less.’

AJ: Do more with less. It’s become Coach Rap’s slogan. He even managed to get it printed on the gym’s floor.

RC: Yeah, I snuck that in here.

AJ: He had to sneak it in, because not everyone likes the language.

RC: ‘Oh you’re telling them that they don’t have enough,’ and I’m like, ‘Well, that’s not the truth.’ They know when they walk into a really nice gym and a really nice track, that there’s a difference between where we live and what’s there. So we engage the difference.

AJ: But the problem is some people think the expression can be used as a cop-out for underfunding schools, maintaining the status quo.

Let’s be clear though, Coach Rap does not believe in the status quo. Here’s an example. William Penn’s football field gets washed out when it rains and it doesn’t have lights, which you need if you want to host a game.

RC: We did something that I think was really good, which is we created Friday Night Lights.

[MUSIC]

AJ: Coach Rap couldn’t afford to buy new lights, so he came up with a solution.

RC: If you drive by at night and the guys are working out there on the highway, we got those same lights, we rented them and we positioned them around the field and we rolled them up as high as we could.

[SOUND OF CHEERLEADERS]

RC: And we started playing games on Friday nights. And it took off.

[SOUND OF A HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL GAME]

It felt alive to you.

AJ: Coach Rap says having home games had a huge impact on his players.

RC: We had announcers and we had like them give guys certain music. So like if a kid made a good play he had his own music, right? It was awesome.

AJ: And the community loved it. Many of them are Penn Wood alumni.

FAN 1: It’s amazing. It’s what it should be in a community. This is football in its purest element.

FAN 2: That’s what Friday Night Lights is all about, bringing the community back.

FAN 3: And that’s what team success does. We don’t just worry about the sports at hand, but we also worry about building that character and getting that kid to believe in themselves.

AJ: An added bonus? Penn Wood’s team went on a winning streak.

[SOUND OF COACH RAP GIVING VICTORY SPEECH]

RC: We went from like a team that won no games to being the number one seed in the district.

AJ: It showed the community what it could be like if they had better facilities. Something the district is now trying to make a reality.

ERIC BECOATS: I’m going to let someone else tell me, no. I’m not going to say no to myself.

AJ: Eric Becoats is William Penn’s superintendent. We heard from him in the first episode. He’s a wiry guy, with a short gray afro, and deep creases in his forehead.

When he arrived in the district a few years ago, he kept hearing about how terrible the facilities were. So he had each school assessed, ranked the projects based on urgency, and came up with a 10-year plan. Athletic facilities made it to the top of the list.

EB: I think it is essential because there are some students without athletics, I don’t know if they would get up and come to school.

[MUSIC]

AJ: Construction is underway on a brand new, $14 million athletic complex that includes a new turf field, synthetic track, baseball and softball fields, locker rooms, concession stands, parking, and restrooms. Things many suburban school districts already have.

EB: The athletic facility is a classroom. Students are learning. They may be learning different things, different ways, but they are learning.

AJ: For this project and others, the district is lining up the money as they go. Superintendent Becoats says he’s been aggressive about applying for grants, from the state…

EB: We got seven million dollars.

AJ: And the federal government. But the community is also taking on debt. The district recently took out a $10 million bond to pay for the athletic complex and other building repairs. In all, the decade-long project is expected to take more than $160 million to complete.

EB: And, you know, there were some people who said, ‘How are we going to pay for this?’ And I’m one of the folks who believe, you know, you don’t say no to yourself.

AJ: You have to try, he says. You can’t just say, ‘We don’t have enough money on hand, so we’re not going to do it at all.’

EB: I think that that is borderline insanity. I believe that you have to develop a plan, set your vision, tell people what you are about, and then work toward trying to achieve it. Even if you don’t reach it.

AJ: I ask Superintendent Becoats what he’d say to people who look at the plan and point to that as evidence that the district is doing OK financially.

EB: We have a plan. We have not executed the plan.

AJ: Then, unprompted, he brings up Coach Rap’s slogan.

EB: Someone said to me, I believe it was our board chair, she said, in the gym, on the floor, I think it says, ‘We do more with less.’

AJ: Coach Curry showed us that when we spoke with him.

EB: That does not need to be the mantra at all.

AJ: People are torn over the language. Remember, Coach Rap snuck it in. Some people see it as the right attitude to have. Others don’t.

EB: I just don’t think that that should become the expectation. At some point, something has to change. It does not have to be this way. It just doesn’t. And I don’t think it’s right.

AJ: While some people are focused on the recent court ruling and the money it could steer toward districts like William Penn, Superintendent Becoats isn’t counting on it.

EB: I am hopeful that the state will respond and do what it is supposed to do. But do I sit here thinking, ‘OK, when is it coming? When is it coming?’ No, because my focus has to be on putting things in place, staying focused on the strategic plan, and trying to make those things happen.

[SOUND OF ENTERING AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL]

AJ: We’re back at Evans Elementary in kindergarten teacher Nicole Miller’s classroom, the one we visited in the last episode. Her students have gone home for the day, but her classroom isn’t empty — her own kids are here.

NICOLE MILLER: I have one child here. The white hoodie there, and my daughter is asleep on the rug over there.

AJ: Two out of her three kids went to Evans, which is also where Nicole went.

[MUSIC]

There’s her daughter Nyla, who got up for our interview.

NYLA MILLER: I’m 18 years old, and in the twelfth grade.

AJ: Her older son.

MARION MILLER: I’m Marion Miller, and I’m 15 years old.

AJ: And her youngest, McCaury. He’s in the fifth grade.

MCCAURY MILLER: I’m 11.

AJ: Nicole loves that she gets to share her world with them. That wherever they go, people know they’re her kids.

NICOLE MILLER: You find across the district that a lot of us have come back. Like a lot of us are still here and teaching who have gone to school here. So it just feels like family.

AJ: She values the close-knit community, but she knows if her kids went to school in another district, even one just a few miles away, they would have more opportunities.

NICOLE MILLER: You know you want to give your kids the best so… I get emotional…

AJ: She asks them a question.

NICOLE MILLER: Would you want it different? Would you rather go somewhere where there are more resources? That’s what I would want to know.

[MUSIC]

MARION MILLER: Absolutely not. I would definitely not. I wouldn’t change a thing. This is my home.

AJ: Nyla comes over and wraps her arms around her mom. She agrees with her brother.

NYLA MILLER: The one thing that we have that I don’t believe other districts have is the source of love and family.

AJ: She echoes what her mom said earlier.

NYLA MILLER: Even my mom, she went here when she was younger. All of her best friends, she has this group chat called the sister circle and all of them were alumni of this district. And not one of them… They all went to college and they all came back and they all work in the district. And some of them have kids that go here. I think that that’s something that we produce here. No amount of money can trade it. I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else because I know nowhere else could produce that, ever.

AJ: How does it feel to hear your kids say that?

NICOLE MILLER: I’m glad to hear that because that’s how I feel. But you know, you often wonder, ‘Am I doing the right thing?’ I love it here. I want to be here. I want to help be a change agent but is it at the cost of my kids? Do they feel like they’re less than others because they see other places that have more? So you try to talk to them at home, ‘Like that’s not what that means. You are deserving of it.’

AJ: It’s clear that her kids know that.

[SOUND OF A KINDERGARTEN CLASS]

For more than 20 years, Nicole has tried to teach her kindergarteners that lesson too.

It’s the same thing Coach Rap is trying to communicate to his players, even as he tells them to do more with less. And it’s the same example that Superintendent Eric Becoats is trying to set by going big with construction instead of holding back.

To be clear, their lesson is that their children, and all children in Pennsylvania, are deserving. And that underfunded school districts like William Penn deserve more than they’ve been getting. More resources, better facilities, and greater opportunities. The things children in wealthier communities have already, and might even take for granted.

And they’re hopeful that with the court ruling, other people will see that now. And that eventually, the money will come.

[MUSIC]

That’s it for this season of Schooled. I’m Aubri Juhasz. Our producers are Michael Olcott and Michaela Winberg.

Our editor is Jamila Bey, and our engineer is Al Banks. Our tile art was made by Robert Dieters. Our executive producers are Sarah Glover and Tom Grahsler.

Special thanks to Maiken Scott, Gabriel Coffey, Kenny Cooper, Grant Hill, Susan Phillips, and Kayla Watkins — and to everyone who spoke with us for this podcast.

In reporting this season, we had help from a lot of sources, including Bruce Baker, Derek Black, Ellen Frede, David Kirp’s book Improbable Scholars, Erika Kitzmiller, Gordon MacInnes, Johann Neem, and Camika Royal.

Thank you to Jonathan Kolleh for sharing footage of Penn Wood’s football games, and to The Public Interest Law Center and the Education Law Center for access to court transcripts and for setting up interviews with the case’s plaintiffs.

Schooled is a production of WHYY. Find us wherever you get your podcasts.

collapse

Business1 week ago

Business1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week ago

Tennessee1 week ago

Tennessee1 week ago

Utah1 week ago

Utah1 week ago

News1 week ago

News1 week ago

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago