New Hampshire

New Hampshire hiker dies after falling near waterfall

A hiker was killed Saturday when he slipped whereas happening a mountain in New Hampshire and fell to the underside of a waterfall, authorities stated.

The hiker, who has not been recognized, rode up Cannon Mountain in a tram with two others and the group was planning on strolling across the summit earlier than heading again down on the tram, the New Hampshire Fish and Sport Division stated.

They modified their minds on the prime and determined to to hike down as an alternative, authorities stated. They weren’t following a climbing path and one of many hikers slipped after they obtained to an space that was rocky, moist and steep, officers stated.

The hiker fell off the sting and was discovered useless by first responders on the backside of the waterfall, officers stated. He was taken to a funeral residence in Littleton.

New Hampshire

Housing in New Hampshire Continues to Become Less Affordable for Buyers and Renters | Manchester Ink Link

Rising housing costs, combined with diminished inventory, create barriers to adequate housing for both homeowners and renters across the Granite State. The median sale price for a single-family house reached a record $515,000 in preliminary data for April 2024, with prices for condominiums slightly decreasing to $400,000. These rising costs and declines of housing inventory contribute to the lack of affordable housing available for individuals and families across the state. Problems facing New Hampshire’s potential homeowners also have negative impacts for renters, particularly among renters with low incomes who are more likely to be cost-burdened by increased prices and less likely to be able to transition to the market for purchasing a home.

Increased Prices for Homebuyers

According to data from the New Hampshire Association of Realtors (NHAR), the median sale price of a single-family house rose to $515,000 in April 2024, a small increase from the revised median price of $499,950 for March 2024. Single-family house prices typically increase during the Spring and Summer months. However, prices have also increased rapidly on an long-term basis, rising by 80.3 percent between the median price of $269,000 for the first four months of 2018 and the median price of $485,000 for the first four months of 2024. The average 30-year fixed rate mortgage for April 2024 was 6.99 percent, and the average 2023 property tax rate across New Hampshire’s cities and towns would result in an annual property tax of $9,439, if it were taxed based on the April 2024 median sale price. Using these figures and a 5 percent down payment of $25,750, a homebuyer would need to pay a monthly mortgage of $4,039 to afford this median-priced house, not inclusive of homeowner’s insurance or private mortgage insurance. Based on the most recently available data from the U.S. Census Bureau, a household would need to spend nearly 54 percent of its monthly income ($7,499 was the median monthly household income estimate for 2022) in order to keep up with mortgage and property tax payments.

While monthly data can be more volatile, condominium prices are also higher thus far in 2024 compared to previous years. The median price of a condominium was $400,001 for the first four months of 2024, a 50.3 percent increase from the median price of $199,000 for the first four months of 2018; this was a larger percent increase than for single-family houses during that same time period (80.3 percent).

New Hampshire’s rising housing prices have surpassed those of neighboring New England states. According to the Maine Association of Realtors, Maine’s prices were lower than New Hampshire in March 2024, with a median price of $380,000 for a single-family house in Maine compared to New Hampshire’s $499,950 for that month. The median price of a single-family house in Vermont was $376,000 in March 2024, according to current data from the Vermont Association of Realtors lower than comparable prices in both Maine and New Hampshire. Although New Hampshire single-family house prices remain lower than Massachusetts, prices have grown slightly faster in the Granite State. In March 2023, the median price of a single-family house in New Hampshire was $447,900, and the price increased by 11.6 percent to $499,950 in March 2024; in Massachusetts, the median price increased by 8.9 percent, from $560,000 in March 2023 to the most recently reported median price of $610,000 in March 2024.

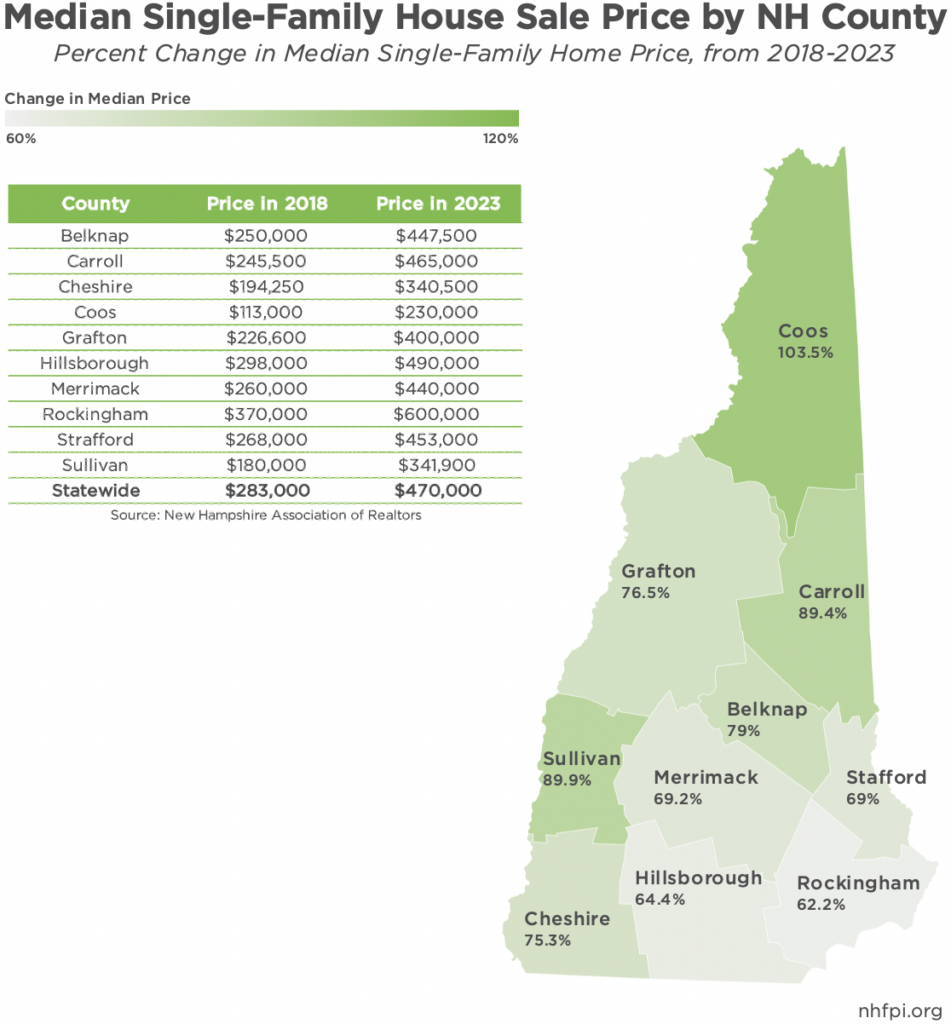

Housing prices differ greatly between New Hampshire counties. In 2023, the median sale prices for single-family houses were highest in Rockingham, Hillsborough, and Carroll Counties, reaching $600,000, $490,000, and $465,000, respectively. While only Coos, Sullivan, and Cheshire Counties experienced median prices under $400,000 in 2023, these counties also had some of the largest percent increases compared to 2018; Coos County median single-single family house prices rose from $113,000 to $230,000 (103.5 percent) between 2018 and 2023, while Sullivan County’s increased from $180,000 to $341,900 (89.9 percent) and the Cheshire County median price rose from $194,250 to $340,500 (75.3 percent). Rising housing prices in certain geographic areas impact where individuals and families are able to live, and can have implications for employment and educational opportunities, social supports, and other necessary resources.

Declining Inventory of Single-Family Houses

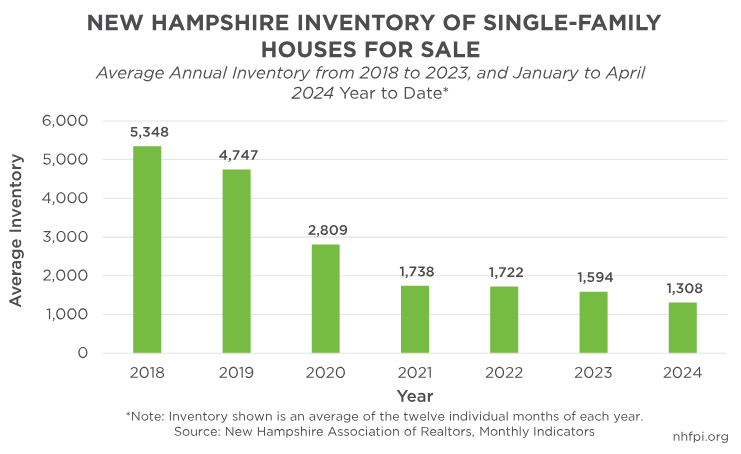

Rapidly increasing housing prices across the Granite State reflect the drastic decline in inventory for single-family houses on the market. According to NHAR, there were a total of 1,435 single-family houses on the market across the entire state in April 2024. While the monthly average of 1,308 houses for sale per month thus far this year is a small increase from the same period in 2023, the 2024 average to date is a 69.9 percent decline from the monthly average of 4,346 houses for the first four months of 2018. Overall, inventory has been on a steady decline on an annual basis since 2018, with the most substantial recent drop occurring between 2019 and 2020.

While inventory has steadily declined since 2018, the number of closed sales for single-family houses across the state rose slightly in 2019 and 2020 before declining again. According to NHAR, there were a total of 11,620 units sold in 2023, a 33.8 percent decline from a total of 17,555 units five years earlier. Rising mortgage interest rates have likely deterred individuals and families from selling their homes, and in turn, have led to declines in housing inventory and increases in prices. The construction of new homes also affects the amount of available inventory. The total number of housing permits issued has increased every year except two between 2011 and 2022, according to the most recent available data from the New Hampshire Department of Business and Economic Affairs. Permits for single-family houses slightly declined from 2,536 in 2021 to 2,495 in 2022, but the total number of units permitted, including multi-family housing construction, increased by an estimated 5,726 in 2022.

Rising Costs for Renters

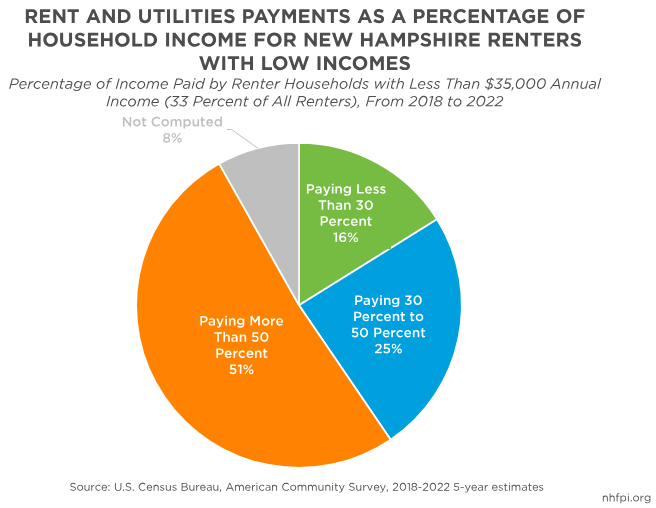

The rise in housing prices has increased costs for Granite State families who rent their homes. As of 2023, the median monthly rent and utilities cost for a two-bedroom apartment was $1,764. Using a simple but reliable measure, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has historically defined families paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing as “cost burdened.” Renters with incomes less than $35,000, or 33 percent of total renters across the state, are more likely to be cost burdened than renters overall in New Hampshire. According to U.S. Census Bureau data collected from 2018 to 2022, nearly half of New Hampshire renters are cost burdened, paying more than 30 percent of their income towards rent and utilities. Among Granite State renters who make less than $35,000 a year, slightly more than a half (51 percent) put more than 50 percent of their income towards rent and utilities. A quarter (25 percent) paid between 30 to 50 percent of their income towards housing costs, while only 16 percent paid less than 30 percent of their household income. Furthermore, eight percent of renters did not have calculated cost burdens due to there being an insufficient number of sample estimates. Increased rental costs leave diminished income for other necessary expenses, such as child care and health care services, and can negatively impact New Hampshire’s economy.

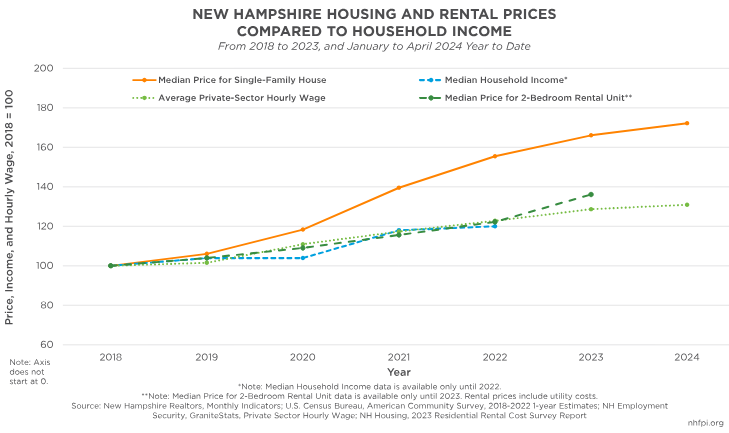

New Hampshire’s median household income and average wages have not kept up with rising housing costs across the state. According to the most recent data, the median household income in New Hampshire was about $90,000 in 2022, which was an increase of 20 percent from the median household income of about $75,000 in 2018. The median price of a single family house grew faster during this time period, from $283,000 in 2018 to $440,000 in 2022, a 55.5 percent increase. Wages have also not grown as quickly as housing prices have, likely making homeownership less achievable for individuals and families, particularly those with low and moderate incomes. From 2018 to 2023, the average private-sector hourly wage in New Hampshire grew by 28.7 percent, while the median monthly cost of rent and utilities for a two-bedroom apartment increased 36.1 percent. Although benchmark rental prices did not substantially outpace median household income or average wage growth between 2018 and 2022, individuals and families who rent their homes typically earn significantly lower incomes compared to homeowners in the state. As of 2022, the median household income for renters was about $56,000 while homeowner median income was approximately $108,000. Although rental prices may be affordable for households with higher-incomes making statewide median household income or more, nearly half of renter-households are cost burdened by rent and utilities.

Rising rental prices may have some association with increases in homelessness. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, a $100 per month increase in median rent was associated with a nine percent increase in the estimated rate of homelessness nationally during the 2012 to 2018 period. Point-in-time estimates, which are typically the most reliable measures for counting the number of individuals experiencing homelessness who are both sheltered and unsheltered, suggest that the number in the state increased from 1,605 to 2,441, or by about 52 percent, between 2022 and 2023; this increase is much larger than the 7.6 percent increase between 2021 and 2022.

Policy Actions and Implications

Recent COVID-19-related federal and State investments in housing have provided economic and financial relief for the thousands of Granite Staters who have been impacted by rising housing costs. As of December 2023, the State’s federally-funded Emergency Rental Assistance Program supported a total of 31,464 renters, providing an average of $10,542 to each approved applicant for rent, utilities, and other eligible household expenses. As of April 2024, the companion Homeowner Assistance Fund has provided $39.2 million to 3,212 homeowners to assist with mortgage, insurance, and property tax payments. In addition, the State’s InvestNH initiative, funded with $100 million of the flexible funds provided to the State from the federal American Rescue Plan Act and another $10 million in State funds, has provided capital grants to developers building multi-family residential units, support for the State’s Affordable Housing Fund, and grants to municipalities to incentivize the permitting of multifamily rental units, help update zoning rules, and aid in demolition of vacant or dilapidated buildings. The current State Budget also provided $25 million directly to the Affordable Housing Fund, $10 million for homelessness and housing shelter programs, and about $5 million for the Housing Champions Program to incentivize municipalities to make infrastructure upgrades to support workforce housing.

Despite these programs’ beneficial impacts, most of the federal funding associated with COVID-19 response legislation has already expired or will have to be committed to its final purpose soon. Further investments, such as increasing the construction of multi-unit houses and continuing to consider reforms to zoning laws to allow more housing density, could help boost the supply of housing. Moreover, increasing access into the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) and HCV Homeownership Programs may help lessen the burden of housing costs for New Hampshire renters with low incomes. Such efforts to expand access to affordable housing across the state support Granite State families, workers, and the overall economy.

Jessica Williams is a policy analyst at the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonprofit, independent policy research organization based in Concord and focused on the state budget, New Hampshire’s economy, and policies affecting Granite Staters, particularly those with low and moderate incomes.

Jessica Williams is a policy analyst at the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonprofit, independent policy research organization based in Concord and focused on the state budget, New Hampshire’s economy, and policies affecting Granite Staters, particularly those with low and moderate incomes.

New Hampshire

UNH's Class of 2024 reflects on a tumultuous few years — and offers words of wisdom

Seniors at the University of New Hampshire donned their caps and gowns this weekend for graduation ceremonies. For many in the class of 2024, college was bookended with upheaval – beginning with the onset of the pandemic, finishing with campus protests of Israel’s war in Gaza, some of which ended in arrests.

For many of this weekend’s graduates, college was also what it has been for generations of alumni: a place to learn new things and meet new friends.

“It’s rare to have this opportunity to be in such a tight-knit community for so many years in a row,” said Seth Rupp, who majored in music. “I don’t know if we’ll have that again in life.”

Rupp said his high school graduation was far from normal – and the start to his college career was disorienting, too.

“Going right into college with virtual classes and kind of limited social capabilities and quarantining and covid testing is kind of a really strange world. So it’s really cool to graduate and kind of have reached a point where it’s sort of normal again,” he said.

The campus protests have been a big part of his last weeks as an undergraduate – he says they’re on everyones’ mind. But he says it wasn’t an interruption – just another part of his college experience.

“I personally was pretty proud of my community, to see people just showing up for what they believe in and using their voices,” he said. “It’s been a little tumultuous and tense, but we made it nonetheless.”

Rupp’s friend Anna Coulobme, who majored in psychology and justice studies, said her favorite parts of college were the new people and opportunities.

“Some of the stuff that I’ve done here I’ve been nervous to do,” she said. “And that’s ended up being some of the stuff that I’m most thankful that I did.”

Advice from the class of 2024

Mason Davis, who studied history and played football, said he didn’t get a real graduation from high school, so this one felt particularly special.

His team won the Coastal Athletic Association conference championships in 2022, which was a highlight. And Davis said making lifelong friends was one of his favorite things about college.

“It’s like a small town in Durham,” he said, “but it’s like a big group of people that always have your back and will support you no matter what.”

His advice for college students is to work hard and seek out advice from professors.

“They’re there to help you, big time,” he said. “Have fun as well, enjoy it. You only get to be in college one time.”

Rachel Dalai, who majored in political science and loved being a resident assistant, said students should make the most of their time in school.

“Make it worth it,” she said. “Do an internship, go abroad. Make good professional relationships.”

Joy Woolley and Clarissa Gowing said the key to college is getting involved — namely through joining clubs and studying abroad.

Both graduated from high school as the pandemic was starting. Woolley’s high school commencement was in a parking lot. She got her diploma in a plastic bag, while her parents watched from the car.

They met on Instagram, and then became friends in a Zoom class, talking on the Zoom chat. Now, they live together. And they started a club, Reading Rainbow, where members read books together by queer authors and authors of color.

“It will build you such a good support system, and you’ll meet so many people that you wouldn’t have otherwise,” Gowing said.

For Gabriela Onasanya, a political science and justice studies major, exploring campus was the best part of college. And having her family watch her graduate on Saturday was exciting.

Her advice? “Be open to new experiences. Be open to new people. Just be open.”

Sam Flynn, who studied mechanical engineering, had similar wisdom: “Join clubs, talk to new people they wouldn’t normally.”

“Find your people. Find people who you click with,” said Adam Dapolit, who majored in political science and international affairs.” And it might not be right away, but just find people who you can surround yourself with and really make the experience what you want it to be.”

Isabella Hart, who studied fine art and food systems, said starting college with the pandemic was tough. But by sophomore year, she’d found her place. She started working as a tour guide and lived with seven roommates.

She was frustrated by the university’s response to protesters earlier this month. But she said it was exciting to see students getting involved and coming together.

Hart was looking forward to graduation, and she said it went by too fast. Her advice for future students is to build community and try new things.

“Get involved and talk to as many people as you can,” she said. “I think you’ll find your connections in the most random places.”

New Hampshire

Solving New Hampshire’s food waste problem one step at a time | Manchester Ink Link

Story Produced by

RELATED STORY: What the science says about food waste

Joan Cudworth had a burst of show-and-tell inspiration in the summer of 2018.

Cudworth, who was then solid waste supervisor for the town of Hollis, came to the select board meeting with a partial solution to tackle the rising costs of trash disposal. She wanted town leaders to fast-track a pilot program to cut down on the amount of food waste being sent to landfills.

“We were looking to reduce trash and taxes,” Cudworth said. “I knew it was a small step. but it was important to get buy-in from the select board.” Cudworth composed at her home and learned how little trash remained after the composting and recycling. She came to the meeting with a transparent, medium-sized bowl containing a week’s worth of food scraps from her house – lettuce, strawberry and radish tops, fruit scrapes, rice, egg shells, cucumber and potato peels. The show-and-tell worked.

“I remember people were fascinated by the possibilities,” Cudworth said. The select board immediately approved money for two Department of Public Works employees to attend the Maine Compost School. By 2019, the pilot program was up and running and collecting around 50 pounds of food waste a week (local schools were already running their own compost programs) at the transfer station. Residents who stopped by were greeted by a composting mascot named “Packalina.”

Cudworth, who became the public works director in 2020, says the total of food waste collected now tops 200 pounds weekly. That may not seem like a lot but, like compound interest, it adds up – to 10,400 pounds annually, which means that the town of about 8,000 residents has diverted more than five tons of food waste from landfills while decreasing climate-harming methane production from food waste fermenting in landfills.

“We are still experimenting and still learning. We don’t know how many are coming to the transfer station or how many residents know about the program,” Cudworth said.

Food waste a state priority

Paige Wilson, waste reduction and diversion planner at the NH Department of Environmental Services, has been busier than normal since the state passed its first food waste ban last summer. The law will go into effect on Feb. 1, 2025. It is focused on entities that generate as much as one ton of food waste a week. That food waste will be prohibited from being sent to landfills. Over the past decade, lawmakers in the nearby states of Vermont, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut have enacted varying levels of food waste disposal bans.

“Food waste is something we all have in common, and composting is a low-hanging-fruit solution,” Wilson said.

It’s also a solution that needs a major expansion of infrastructure. Wilson is the education outreach and planning person, and her job is to assist commercial and municipal organizations, so she sees firsthand that food waste diversion in New Hampshire needs a major expansion of public and private infrastructure for a more sustainable path.

“There are a lot of factors that go into a sustainable (food waste diversion) program: budgeting, staffing, feasible space” for larger-scale composting, she said.

Another issue will be addressed in the coming year. The U. S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated that state residents put more than 180,000 tons of food waste into landfills — about 24 percent of all waste. But no on-ground studies have been done to better approximate the actual amount. Wilson said more comprehensive studies have been funded and will be launched – by literally sorting through trash.

“We’ve never had a state (food waste) characterization study on the amount of food. We will do one now by literally hand-sorting through 250 pounds of waste to get data,” Wilson said. Because the state has made food waste a priority, a diverse constituency of summer camps, municipalities, hospitals, schools, hospitals, nursing homes and any organizations that generate food waste has heard the call and reached out to find out what they can do.

“What you are seeing is a huge resurgence of interest in solid waste and recycling,” said Rep. Karen Ebel, D-New London, the prime sponsor of the bipartisan food waste ban legislation and chair of the state’s Solid Waste Working Group. “I feel like we are making progress.”

In particular, she said, it was a positive step that 50 percent ($500,000) of the state’s Solid Waste Municipal Fund appropriated by the legislature to food diversion efforts will include staffing and grants.

The cost of infrastructure

It’s not easy to come up with a solid estimate on the cost of building out a food waste recovery infrastructure.

According to Paige Wilson, “New Hampshire will need infrastructure investments all along the food recovery chain, but the costs vary so much depending on where you’re at in the chain. The price tag for buying a refrigerator at a food bank looks different than the costs of purchasing equipment at a composting facility. I’d say it’s going to take millions of dollars to build the needed infrastructure across New Hampshire, in order to reach our disposal reduction goals set in statute (25 percent reduction in landfill solid waste by 2030 and 45 percent reduction by 2050).”

Reagan Bissonnette, executive director of the Northeast Resource Recovery Association, agreed that it will cost millions, but patience, innovation and more legal requirements will be needed.

“Infrastructure money is not enough. Other states have found that without a landfill ban on some food waste in place, it’s difficult to have enough food waste supply to make an investment in infrastructure financially viable in the long term,” she said. “An example is the Waste Management Core facility in Massachusetts. Even with a statewide food waste ban in place, it took longer than they expected to get enough supply from businesses and others to get the facility operating at capacity.”

Vermont, said Wilson, is “a New England state to learn from because they’re in a territory right now that is unknown to the rest of us. A statewide food waste disposal ban that applies to everyone comes with a lot of learning curves, new systems, and innovation.”

Over the years, said Bissonnette, Vermont has implemented tiered food waste disposal bans over time. They started with banning disposal of food waste from large generators of waste (like hospitals and universities), then slowly lowered the generation amount until all food waste, even from residential homes, cannot be landfilled.”

Making composting work

At its Kingman Farm research facility, the University of New Hampshire in Durham has one of the largest compost-creating operations in the state, and it has been operating since the mid-1990s. Colleen Stewart at the New Hampshire Food Alliance (which is part of the UNH Sustainability Institute), said UNH had one of the first campus compost programs in the country. In 2023, UNH dining halls sent 386,260 pounds of food pulp to Kingman Farm composting rows, which creates nutrient-rich soil. That soil is used by students to create crops for some of the produce served at UNH dining halls.

In a June 2023 UNH Today article detailing the composting program, Anton Bekkerman, director of the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station at Kingman Farm, said, “the program here at UNH really highlights that even without large investments into infrastructure and labor that a composting program can be implemented by the Granite State’s smallest towns and village to ultimately reduce waste and provide a nutrient-rich additive to gardens and farms.”

The topic of food waste diversion was front and center during two days of workshops in April hosted by the Northeast Resource Recovery Association. Bissonnette said her Epsom-based organization has been targeting food waste diversion for the past five years, in addition to more than four decades of recycling educational efforts. She said about 50 people from municipalities and businesses from across the state attended the four workshops, which were co-hosted by the N.H. Department of Environmental Services and the Maine Compost School.

Bissonnette said among the many points covered at the workshops – which were free, courtesy of a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant – participants learned a few surprising truths about food waste:

- Most wasted food is generated by households (almost 43 percent), not manufacturers or retailers.

- In 2022, roughly 38 percent of the U.S. food supply went unsold or uneaten.

- Preventing wasted food has a bigger positive environmental impact than composting wasted food.

“One town concluded that they need to send a mailer to their entire town to effectively get out the word about their existing composting program,” she said.

The topic of food waste diversion will be the focus of a keynote panel at the NRRA annual conference in Concord in June. Later this year, she said, NRRA will conduct its first bus tour focused on waste diversion programs at various landfills and transfer stations.

Citizen involvement

Not unlike Joan Cudworth in Hollis, Paul Karpawich was inspired to do something positive to tackle the climate change crisis as a lone citizen.

“I feel that people can be overwhelmed about climate change,” said Karpawich, who had migrated north from Massachusetts and was living in the southern New Hampshire town of Brookline when he began looking at the bigger picture of long-term sustainability. The veteran of the high-tech industry said he “kind of gravitated” to food waste diversion in part because “food waste is so prevalent in our society,” and it was something everybody could do.

Karpawich had no title and few contacts, but he persevered, and in 2022 created the New Hampshire Food Waste Diversion and Sharing Initiative with the help of small grants from the World Wildlife Fund and U.S. Department of Agriculture. The program is a collaborative effort between individuals, schools and towns to develop best practices that reduce food waste and prevent it from going to landfills.

More importantly, he focused on elementary and secondary school students to get them involved early. “By taking small concentrated steps this can be a catalyst for students, schools and towns to create a long-lasting paradigm shift for a transition to a more sustainable future,” he said. He has seen the impact of schools institutionalizing their efforts, with a few school boards allocating budget funds for the pickup of composting loads.

The initial success of the program has led to more grants and increased ability to jump-start food waste diversion programs at schools. The initiative has spread from the elementary school in Hollis, the first participant, to schools in Northwood, Bethlehem, Hopkinton (where Karpawich now lives) and others. He said the educational aspects of the program (math, science and environmental awareness) have been matched by a remarkable level of dedication by students who get involved.

“When kids do this, they are very present, not looking at their phones. I have seen at the elementary and high school levels that they become very passionate and take ownership of the programs at their schools,” he said.

Find out more: NRRA offers a Waste Reduction and Diversion Toolkit, a list and links to almost 20 municipalities offering food diversion and composting programs, and a list of farms and pick-up services serving New Hampshire.

The EPA is awarding between $10 million and $20 million in Environmental and Climate Justice Community Change grants for multi-faceted projects addressing a range of pollution, climate change, and other priority issues, including food waste diversion. This application period goes through November.

These articles are being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.

These articles are being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIndia Lok Sabha election 2024 Phase 4: Who votes and what’s at stake?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics: No calm after the Stormy

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUkraine’s Zelenskyy fires head of state guard over assassination plot

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSkeletal remains found almost 40 years ago identified as woman who disappeared in 1968

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoUS Border Patrol agents come under fire in 'use of force' while working southern border

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTales from the trail: The blue states Trump eyes to turn red in November

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBorrell: Spain, Ireland and others could recognise Palestine on 21 May

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCatalans vote in crucial regional election for the separatist movement