Boston, MA

Boston, Reno, Savannah Are Best For St. Patty’s Day, According To New Report

The parade is an integral part of St. Patrick’s Day in Boston, which personal-finance website WalletHub says is the best city to celebrate the occasion. (Photo by Scott Eisen/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Boston has celebrated St. Patrick’s Day with a parade through the streets of South Boston for more than 300 years, and up to 1 million people, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority says, are expected to attend the parade this year. With such popular support, it may not be surprising that a new report names Boston as the best American city to be in to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.

The report by personal-finance company WalletHub compared the 200 largest U.S. cities by 15 metrics, including Irish pubs and restaurants per capita, the lowest prices for a three-star hotel on St. Patrick’s Day and the expected weather.

“Boston is the best city for celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, and it’s known for its iconic parade, which has been around since 1724,” says WalletHub writer and analyst Chip Lupo. “Over 13% of the city’s residents have Irish roots, and Boston has the sixth-most Irish pubs and sixth-most Irish restaurants per capita.”

The parade will be held on March 16, a day before St. Patrick’s Day, beginning at 11:30 a.m at Broadway station. The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority posts a St. Patrick’s Day guide and a map of the day’s parade route on its website.

“Due to street closures and parking bans in the neighborhood, driving to the parade is not recommended,” the authority says. “Please plan ahead for your trip — you may need to wait longer than usual to get on a train.”

If you are not a local resident or don’t plan a trip to Boston, there are numerous other cities with top-flight St. Patrick’s Day celebrations, the WalletHub report says.

The second-best city is Reno, Nevada, and Savannah, Georgia ranks No. 3. Rounding out the top 10 in WalletHub’s report are No. 4 Santa Rosa, California, followed consecutively by Worcester, Massachusetts; Chicago; New York; Henderson, Nevada; Buffalo, New York, and Pittsburgh.

“The best cities for St. Patrick’s Day combine rich traditions with tasty and affordable food, safe conditions to celebrate and good weather,” Lupo says. “Celebrating in one of these cities will increase your chances of having a memorable holiday, as long as you don’t overdo it.”

The report also uncovered some unique findings:

*New York has the most Irish pubs per capita — nearly 35 times more than San Jose, California, the city with the lowest number. New York also has one of the lowest rates of DUI-related fatalities — 32 times less than in Salem, Oregon, the city with the highest rate.

*Naperville, Illinois has the highest share of Irish population — 48 times greater than in Hialeah, Florida, the city with the lowest share. Naperville also has the lowest violent-crime rate — nearly 57 times lower than Oakland, California, the city with the highest rate.

*Milwaukee, Wisconsin has the lowest average beer price — 1 1/2 times less expensive than in Anchorage, Alaska, the city with the highest average price.

Tampa, Florida, turns the river waters green for its St. Patrick’s Day celebration, which is held on the Saturday before March 17. Tampa Downtown Partnership

Tampa, Florida, which ranks No. 21 in the report, holds its St. Patrick’s Day celebration on Saturday, March 15, and colors its river waters green.

A Saturday celebration allows more people to enjoy the festivities without worrying about work the next day, says Caroline Keesler, a Tampa Downtown Partnership marketing and communications official.

About 20,000 people attended Tampa’s St. Patrick’s Day celebration last year, and more are expected this year, Keesler says.

The festivities will include artist Trisha Sham, who will paint throughout the event, and a five-piece Celtic band called the Irish Buskers. The headline musical act is George Pennington & the Odyssey, a local band that fuses rock, blues, funk and jazz into its performance.

Boston, MA

Charlotte plays Boston on 5-game win streak

Charlotte Hornets (31-31, ninth in the Eastern Conference) vs. Boston Celtics (41-20, second in the Eastern Conference)

Boston; Wednesday, 7:30 p.m. EST

BETMGM SPORTSBOOK LINE: Celtics -6.5; over/under is 214.5

BOTTOM LINE: Charlotte is looking to keep its five-game win streak alive when the Hornets take on Boston.

The Celtics are 27-13 against Eastern Conference opponents. Boston is sixth in the NBA with 46.2 rebounds led by Nikola Vucevic averaging 8.8.

The Hornets are 19-21 in conference matchups. Charlotte is 7-8 when it turns the ball over less than its opponents and averages 15.0 turnovers per game.

The Celtics average 15.5 made 3-pointers per game this season, 2.7 more made shots on average than the 12.8 per game the Hornets allow. The Hornets average 16.0 made 3-pointers per game this season, 2.1 more made shots on average than the 13.9 per game the Celtics allow.

TOP PERFORMERS: Jaylen Brown is averaging 29 points, 7.1 rebounds and five assists for the Celtics. Payton Pritchard is averaging 17 points and 5.8 assists over the past 10 games.

Kon Knueppel is averaging 19.2 points, 5.5 rebounds and 3.5 assists for the Hornets. Brandon Miller is averaging 22.7 points, 5.3 rebounds and 3.6 assists over the past 10 games.

LAST 10 GAMES: Celtics: 8-2, averaging 109.4 points, 50.7 rebounds, 27.1 assists, 6.1 steals and 6.4 blocks per game while shooting 45.7% from the field. Their opponents have averaged 98.5 points per game.

Hornets: 7-3, averaging 117.3 points, 47.8 rebounds, 27.4 assists, 8.5 steals and 4.2 blocks per game while shooting 45.6% from the field. Their opponents have averaged 106.2 points.

INJURIES: Celtics: Jayson Tatum: out (achilles), Neemias Queta: day to day (rest).

Hornets: Coby White: day to day (injury management).

___

The Associated Press created this story using technology provided by Data Skrive and data from Sportradar.

Boston, MA

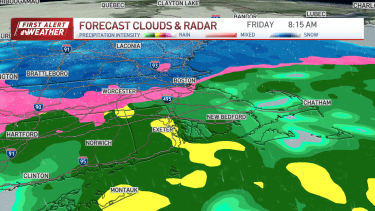

First Alert: Mix of snow and rain today, then looking ahead to warmer weather

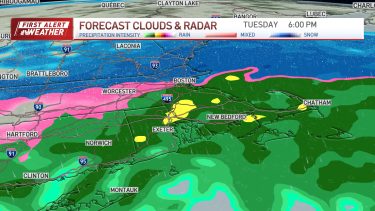

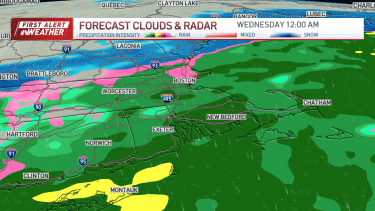

Today is a First Alert weather day. A system to our south is pushing mix of snow and rain into southern New England through this evening and tonight.

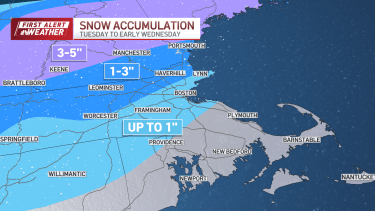

For us here in Greater Boston, expect snow to continue spreading over our area through the afternoon/evening commute. In fact, parts our area could see up to 1 to 2 inches of snow accumulation before the sleet and rain move in.

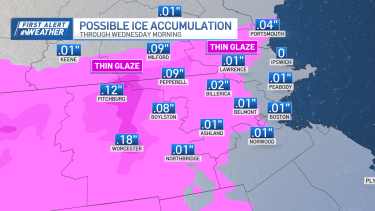

Much of Greater Boston will likely see snow amounts on the lower end. Higher snow amounts are expected toward southern New Hampshire and along and north of outer Route 2. Also, some ice accumulations are possible, up to a tenth of an inch, creating a thin glaze here and there.

Dozens of schools in Connecticut and Massachusetts have already announced early dismissals as a result of the storm.

While this system won’t cripple our area, conditions could still create a mess on the roads during the evening commute through tonight. Be careful while driving. A Winter Weather Advisory remains in effect for parts of our area through early Wednesday morning. High temperatures will be in the mid to upper 30s today. Overnight lows will drop into the low 30s.

We’ll wake up to patchy fog Wednesday morning before the sun returns. High temperatures will be in the upper 40s. We’ll stay in the 40s on Thursday with increasing clouds. But by late Thursday night into Friday, wet weather returns. Some snow could mix with the rain into Friday morning. Highs will be in the upper 30s Friday.

Warmer weather is expected this weekend. Highs will be in the 50s Saturday and possibly near 60 on Sunday.

Boston, MA

Boston police officials dominate the list of highest-paid city workers in 2025 – The Boston Globe

That was more than what every other city department spent on overtime combined, though it was a slight drop from the $103 million the police department spent on overtime in 2024.

High overtime spending inside the police department has long been controversial and a source of frustration for police-reform advocates. Last year’s nine-figure total comes as Mayor Michelle Wu warns of a challenging budget season to come for the city, which is grappling with inflation and the possibility of more federal funding cuts.

In a December letter, Wu told the city council that she instructed city department heads to find ways to cut 2 percent of their budgets in the next fiscal year. She also imposed a delay on new hires. Boston Public Schools Superintendent Mary Skipper has also proposed cutting somewhere between 300 and 400 positions next fiscal year due to budget constraints.

Overall, the city spent about $2.5 billion on employee salaries in 2025, up around 1.5 percent from $2.4 billion in 2024. The city employs roughly 21,000 workers, according to a public dashboard.

In a statement, Emma Pettit, a spokesperson for Wu’s office, attributed the payroll increase to raises, and in some cases, employees receiving retroactive pay, that were part of contracts the city negotiated with its various labor unions.

“We’re grateful to our city employees for their hard work to hold Boston to the highest standard for delivering city services,” Pettit said.

When Wu won her first mayoral race in November 2021, all of the city’s 44 union contracts had expired. Since then, Wu’s office has negotiated new agreements with all of them, and last year, agreed to a one-year contract extension with the Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association, the city’s largest police union.

But as the city heads back to the bargaining table to negotiate extensions or new contracts with others, city leaders should keep cost at the forefront of those conversations, said Steve Poftak, president of the Boston Municipal Research Bureau, a business-backed budget watchdog group.

“As budgets tighten, I’m hopeful that it increases the scrutiny on these collective bargaining agreements,” Poftak said.

The top earner on the city’s payroll last year was Boston Police Captain Timothy Connolly. In addition to his $194,000 base salary, Connolly took home nearly $230,000 in overtime, about $26,000 in undefined “other pay,” and roughly $49,000 as part of a higher-education bonus, for a total of $498,145 in compensation.

Skipper, as BPS superintendent, was the 55th-highest earner among city workers, coming behind 54 members of the police department. She made a total of $378,000 in 2025.

Nearly 300 city employees made more than $300,000 last year. In contrast, Wu made $207,000, though her salary increased to $250,000 this year. More than 1,700 city employees made more than the mayor in 2025.

Larry Calderone, president of the Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association, argued that the high overtime costs in the police department are, in part, a result of understaffing.

The department is short roughly 400 rank-and-file police officers, Calderone said, meaning the department has to pay its staff to work overtime and fill vacant shifts. The average salary for an officer in the BPPA is roughly $195,000, Calderone said.

With several large events approaching, including a Boston-based fan fest around this summer’s World Cup matches and the return of a fleet of tall ships to Boston Harbor, Calderone said most of the members of his union are likely to be working the maximum allowable 90 hours a week.

“We just don’t have the bodies on the street,” he said.

The Boston Police Department and the Boston Police Superior Officers Federation — the union that represents the department’s sergeants, captains, and lieutenants — did not immediately return requests for comment Monday.

Jamarhl Crawford, an activist and former member of the Boston Police Reform Task Force, said while high spending on overtime is not new for the police department, it’s a pressing problem the city should tackle.

The police and fire departments are “essential components of the city and society in general … [and] folks should be getting a fair wage. But it also has to be within fiscal responsibility,” Crawford said.

“In another 10 years,” he continued, “with pensions and everything else, this type of thing can bankrupt the city.”

Niki Griswold can be reached at niki.griswold@globe.com. Follow her @nikigriswold. Yoohyun Jung can be reached at y.jung@globe.com.

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts7 days ago

Massachusetts7 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO7 days ago

Denver, CO7 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Florida3 days ago

Florida3 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Maryland3 days ago

Maryland3 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Thrilling Books That Became Popular Movies