Lifestyle

Sunday Puzzle: Cyber Monday categories!

Sunday Puzzle

NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

NPR

On-air challenge: Tomorrow is Cyber Monday. I’ve brought a game of Categories based on the word CYBER. For each category I give, name something in it starting with each of the letters C-Y-B-E-R.

For example, if the category were “Two-Syllable Girls’ Names,” you might say Connie, Yvette, Betty, Ellen, and Rachel. Any answer that works is OK, and you can give the answers in any order.

- Colors

- Garden Vegetables

- Mammals with Three-Letter Names

- Popular Websites

Last week’s challenge: Last week’s challenge comes from listener Greg VanMechelen, of Berkeley, Calif. Name a state capital. Inside it in consecutive letters is the first name of a popular TV character of the past. Remove that name, and the remaining letters in order will spell the first name of a popular TV game show host of the past. What is the capital and what are the names?

Challenge answer: Montgomery (Ala.) –> Gomer (Pyle), Monty (Hall)

Winner: Greg Felton of Stateline, Nev.

This week’s challenge: This week’s challenge comes from the crossword constructor and editor Peter Gordon. Think of a classic television actor — first and last names. Add a long-E sound at the end of each name and you’ll get two things that are worn while sleeping. What are they?

Submit Your Answer

If you know the answer to the challenge, submit it here by Thursday, December 5th, 2024 at 3 p.m. ET. Listeners whose answers are selected win a chance to play the on-air puzzle. Important: include a phone number where we can reach you.

Lifestyle

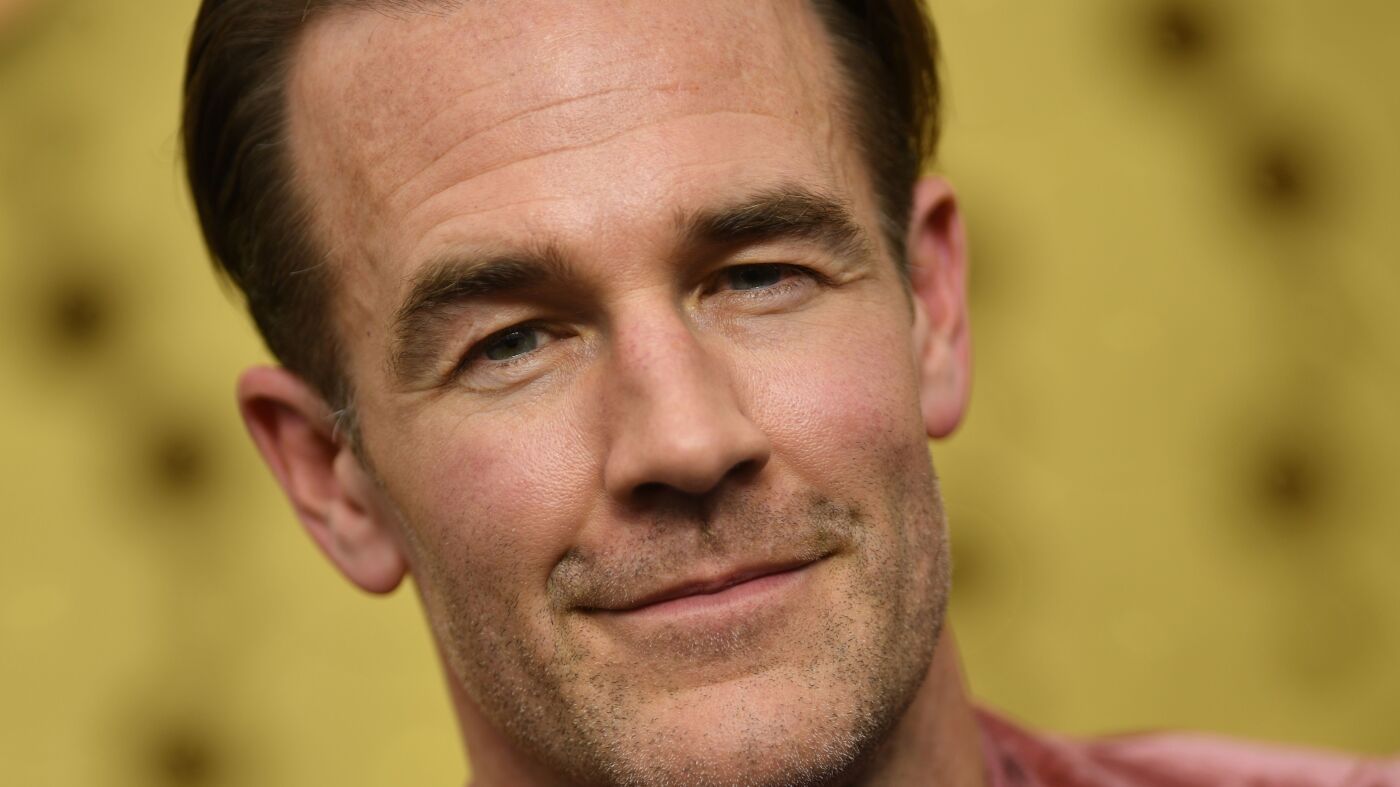

‘Dawson’s Creek’ star James Van Der Beek has died at 48

Actor James Van Der Beek arriving at the Emmy Awards in 2019.

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

James Van Der Beek — best known for his role as Dawson Leery in the hit late 1990s and early aughts show Dawson’s Creek — has died. He was 48. Van Der Beek announced his diagnosis of Stage 3 colon cancer in November 2024.

His family wrote on Instagram on Wednesday, “Our beloved James David Van Der Beek passed peacefully this morning. He met his final days with courage, faith, and grace. There is much to share regarding his wishes, love for humanity and the sacredness of time. Those days will come. For now we ask for peaceful privacy as we grieve our loving husband, father, son, brother, and friend.”

Van Der Beek started acting when he was 13 in Cheshire, Conn., after a football injury kept him off the field. He played the lead in a school production of Grease, got involved with local theater, and fell in love with performing. A few years later, he and his mother went to New York City to sign the then-16 year old actor with an agent.

But Van Der Beek didn’t break out as a star until he was 21, when he landed the lead role of 15-year-old Dawson Leery, an aspiring filmmaker, in Dawson’s Creek.

Van Der Beek’s life changed forever with this role. The teen coming-of-age show was a huge hit, with millions of weekly viewers over 6 seasons. It helped both establish the fledgling WB network and the boom of teen-centered dramas, says Lori Bindig Yousman, a media professor at Sacred Heart University and the author of Dawson’s Creek: A Critical Understanding.

“Dawson’s really came on the scene and felt different, looked different,” Bindig Yousman says.

It was different, she points out, from other popular teen shows at the time such as Beverly Hills, 90210. “It wasn’t these rich kids. It was supposed to be normal kids, but they were a little bit more intelligent and aware of the world around them … It was attainable in some way. It was reflective.”

The Dawson’s drama centered around love, hardships, relationships, school and sex — sometimes pushing the boundaries when it came to teens discussing sex. Van Der Beek’s character Dawson was a moody, earnest dreamer, sometimes so earnest he came across as a “sad sack,” says Bindig Yousman. He had a seasons long on-again off-again on-screen relationship with his best friend Joey, played by Katie Holmes. Bindig Yousman says Van Der Beek quickly became seen as a heartthrob.

“I think he was very safe for a lot of tweens, and that’s when we started to get the tween marketing,” she says, referring to the attention paid to him by magazines like Teen People and Teen Celebrity. “And so because he wasn’t a bad guy, he was conventionally attractive … He definitely appealed to the masses.”

Dawson’s Creek launched the careers of not just of James Van Der Beek, but his costars Katie Holmes, Joshua Jackson and Michelle Williams. All went on to have successful careers in the entertainment industry.

Despite his success, Van Der Beek didn’t land many roles that rose to that same level of fame he enjoyed in Dawson’s Creek. Perhaps because audiences associated him so much with Dawson Leery, it was difficult to separate him from that character.

Still, he starred in the 1999 coming of age film Varsity Blues, as a high school football player who wants to be more than just a jock. In 2002’s Rules of Attraction, he played a toxic college drug dealer.

And he actually parodied himself in the sitcom Don’t Trust the B—- in Apartment 23. In it, he’s a self-obsessed actor unsuccessfully trying to get people to see him as someone other than the celebrity from Dawson’s Creek. In an episode where he decides to teach an acting class, the students ignore the lesson and instead pester him to perform a monologue from the show.

In real life as well, the floppy blond-haired Dawson Leery is the one that stole fans’ hearts, but Bindig Yousman says Van Der Beek still enjoyed a strong fanbase that followed him to other shows, even when they were only smaller cameos.

In the 2024 Instagram post about his cancer, Van Der Beek said “Each year, approximately 2 billion people around the world receive this diagnosis … I am one of them.” (There were about 18.5 million new cases of cancer around the world in 2023, a number that researchers say is projected to rise.) Van Der Beek leaves behind six children.

The cast of Dawson’s Creek reunited to raise money for the nonprofit F Cancer, which focuses on prevention, detection and support for people affected by cancer. They read the pilot episode at a Broadway theater in New York City in September 2025. His former co-star Michelle Williams organized the reunion. James Van Der Beek was unable to perform, due to his illness, but contributed an emotional video that was shown onstage. In it, he thanked his crew and castmates, and the Dawson’s Creek fans for being “the best fans in the world.”

Lifestyle

For Mel Depaz, the streets of Compton are her studio

As a muralist, Mel Depaz is a storyteller. But when you look at her work overall, it’s clear how much her surroundings influence what she puts down with her brush. She’s all about community.

Mel’s paintings are about Compton and the elements that make up the city. I think that her work is very important because it allows the people who live here to have a visual of their community. For example, her mural featuring the Compton Cowboys. When you come through the city, you don’t really just see people riding horses around at all times of day. Then Mel’s work makes you wonder: Where are they at? How do I get close? Her work is inviting the public to take a closer look.

I met Mel at her family home on the east side of Compton, before we took a short drive to see her murals. Like her large-scale work, Mel’s paintings told the story of our shared city.

Mr. Wash: All of your work and your whole practice is in the outside space. Let’s talk about it in the sense it’s your studio. What do you like about it?

Mel Depaz: Getting to know the neighborhood. I don’t use spray paint. I only brush, so it takes me a while. I usually spend a week minimum on a mural, and I get to know the regulars. People are really nice — at least they’ve been nice to me. I’ll get offered free food, sometimes free drinks.

I feel like I know different areas of L.A. pretty intimately. I’ve been outside and I’m watching all the cars and seeing the people go by. I like that aspect. And then I also like being away from home all day and coming back and being tired. I like being exhausted at the end of the day. It’s a good feeling. Like, damn, I really put a lot into the wall.

MW: What do you not like about it?

MD: Sometimes it can be sketchy and you feel vulnerable. The other day I was up in the ladder and I had a box of brand-new paint, and some guy just got out of a car and stole it. But then he came back ten minutes later. He was like, “I’m sorry, I had a change of heart.”

MW: Really? Wow. Can you talk through the practicalities of having an open-air practice?

MD: The reason I haven’t moved into a studio or rented one is because as a muralist, you don’t really need it; the outside is your studio. So I just have a car. I’d rather spend what I would on a studio on a car, ’cause I need a big one. I have to think about transportation and space and things like that.

MW: I go down to Texas to work with my nephew Poncho. He’s a mural artist. He basically works out of the bed of his truck, going back and forth. So you are working as an artist here in Compton, you mentioned you have a car. Is it a hatchback? Is it an SUV?

MD: A Jeep. A Wrangler. It has storage capacity for buckets and stuff. I used to drive an older Camry and it got to the point where I was crossing ladders through the passenger seat and I popped the spraycan in the backseat. I ran it through. So I was like, OK, I can get a used car. But I also had used car trauma — my check engine light coming on, my dashboard lights. So I thought, I can get a used car or just get a new car with space. And I really needed one that’s closed. If I bought a truck, someone could steal my stuff while I get lunch. With the Jeep, I’ve been good at keeping it clean. I’m thinking about buying it. But that’s why I was like, let me get a car instead of a studio, because that’s really what I need.

MW: Smart decision. How long have you been a muralist?

MD: Six years. The NHS [Neighborhood Housing Services, Center for Sustainable Communities] one was my first mural.

MW: Can we talk about that connection?

MD: That was the first time I saw you. That was crazy. I came to the opportunity to paint that mural because I did a painting for Patria Coffee. That’s the first Compton-based painting I had ever done.

They had a regular who worked at the center at NHS, and he got my Instagram. He was like, I see you don’t have any mural experience, but we need a muralist. Do you mind finding another Compton artist that might have experience? I’d seen Anthony [Lee Pittman, also featured in this book] at a show maybe a month before. So I DMed Anthony like, “Hey, I got this opportunity. I have a meeting tomorrow. Do you want to be part of it?” We met literally 15 minutes before the meeting and we got the job.

When I was painting with Anthony, you came one day. I had just got off the scissor lift and then you said you were supposed to paint the wall, but got too busy. I was like, that’s crazy.

MW: Yeah. That was crazy. That was way back. What was it about the first mural that had you hooked and wanted to keep on doing them?

MD: I think I just liked being able to drive somewhere and stare at how big it was. I’ve always been a fan of street art and outside work, and even graffiti is a pathway to that. I’ve never been good at graffiti or none of that. So I just brought what I learned in school through painting to walls.

I grew up in the east side of Compton, and I would say I feel more connected to Compton overall now that I’ve been in little pockets of it through several hours and days.

— Mel Depaz

MW: Well, you’re very good at what you do. Neat, clean, and a storyteller. How many murals have you got in Compton?

MD: I’ve done 27 total, and 14 in Compton.

MW: How do you think painting murals in Compton has changed your relationship with the city?

MD: I grew up in the east side of Compton, and I would say I feel more connected to Compton overall now that I’ve been in little pockets of it through several hours and days.

I wouldn’t sign the first few murals I did because I wasn’t really too happy with what I was doing. I still felt like I was learning. But these last ones that I painted I signed them. This older Latino man came up to me and he was like, “Hi, mija. I’ve seen your work before. I want to say thank you for everything that you’ve done. I’ve looked for your name and I haven’t been able to find it, and I’m so happy that you’re here.” And then he gave me some lunch money. I guess he was religious, and he blessed me.

It was a cute moment because I didn’t even know people knew of me. And there’s little moments like that where it’s like, oh people are really watching and you don’t even realize.

MW: I was thinking that a lot of people who live in Compton, they’re seeing your work as part of their everyday, and there’s something really special about that.

MD: Lately I feel more proud of what I’ve been doing. There’s more sense of like, damn, I really did that. But in the beginning it was kind of that imposter syndrome. Like, I don’t really know what I’m doing, but I’m just going to keep doing it.

MW: That’s how it grows. Listen, same here. When I painted the first picture, I knew what I wanted to try to do, but when it came out onto the brushes, it wasn’t what I had in my head. It was just something totally different.

I was like, should I start over? Should I quit? Should I throw it away? I said, no, I’m going to keep it and I’m going to find lessons inside of that and just build off of that. You get better and better.

This interview was excerpted from Artists in Space by Mr. Wash, available to order on Feb. 16. Fulton Leroy Washington, a.k.a. Mr. Wash, is a Compton-based, self-taught artist and criminal justice reform advocate. All book sales will go toward the Art by Wash Studio & Community Center. Mr. Wash’s work has been exhibited at Jeffrey Deitch L.A., the Hammer Museum, LACMA, the Huntington Library, Palm Springs Art Museum and more.

Lifestyle

February may be short on days — but it boasts a long list of new books

In the United States, at least, February is a time for remembering — the feats of Black communities in America, the lives of its greatest presidents, the plight of a single large frightened rodent, even love itself (and its various totems that you’re expected to purchase).

Whew, that’s a whole lot of remembering to pack into the shortest month of the year. So, if only for the next few weeks, you have our permission to forget your guilt-inducing backlog of books and just dive right into the new stuff — which includes highly anticipated new releases from Michael Pollan, Tayari Jones and the late Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa.

Autobiography of Cotton, by Cristina Rivera Garza, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney — Feb. 3

Rivera Garza won the Pulitzer Prize for 2023’s Liliana’s Invincible Summer, a “genre-bending account“ of her sister’s life and murder that blends elements of memoir, investigative journalism and history. Autobiography of Cotton is the second book from the Mexican author’s backlist to receive an English translation since her Pulitzer win, and it shares a characteristic disdain for compartmentalization. This time she weaves in enough historical fiction to warrant calling this Autobiography a “novel.” But that label doesn’t fit either, as this hybrid account of ill-starred cotton farmers in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands also contains enough historiography and personal family history — among other disciplines — to again twist its would-be shelvers into pretzels, in a good way.

Biography of a Dangerous Idea: A New History of Race, from Louis XIV to Thomas Jefferson, by Andrew S. Curran — Feb. 10

There’s a curious thing that happens with ideas. Often it’s the most historically contingent ones — and occasionally the most pernicious — that claim to be eternal, universal or “self-evident.” In this new history, Curran, a scholar of the Enlightenment, offers a fascinating reassessment of that heady era of Western philosophy: how its towering thinkers came to invent the very idea of race as we know it today, and how that biological balkanization of humanity came to be passed down, quite misleadingly, as some sort of eternal truth.

A World Appears: A Journey into Consciousness, by Michael Pollan — Feb. 24

Few journalists have spent as much time as Pollan thinking about the kinds of stuff we put into our bodies. The author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma has considered food intensively from every angle — how it’s grown, cooked, processed and consumed — as well as substances such as caffeine and mind-altering plants. Now, the “reluctant psychonaut” is training his gaze on thinking itself. His new book probes our understanding of what it means to, well, understand — a concept that’s as crucial to our notion of what it means to be human as it is elusive and downright paradoxical.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

I Give You My Silence, by Mario Vargas Llosa, translated from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West — Feb. 24

“Each book, for me, has been an adventure,” Vargas Llosa told NPR just hours after he won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature. Perhaps it’s fitting that the fruit of his final adventure, I Give You My Silence, reaches English-language readers only after his death last year at age 89. While he was alive, the Peruvian author (and activist, presidential candidate and alleged literary feuder) wasn’t often associated with silence. Vargas Llosa’s last novel centers a professor seeking the soul of his country in music. Published in Spanish in 2023, the book is now being brought to English readers by way of Adrian Nathan West, who also translated 2021’s Harsh Times.

Kin, by Tayari Jones — Feb. 24

“Every true story is in the service of justice. You don’t have to aim at justice; you just aim for the truth,” Jones told me in 2019, just minutes after her previous novel, An American Marriage, won the Aspen Words Literary Prize. Judging just from back-cover synopses, Kin, Jones’ first novel since that portrait of love caught in the grinder of mass incarceration, would seem more concerned with character and the complexities of friendship than Justice with a capital J. But as Jones herself warned, such distinctions can be misleading. Here a single relationship between two black women, rendered with Jones’ care and capabilities as a writer, becomes a prism through which to view a complex generation in the American South.

Brawler, by Lauren Groff — Feb. 24

Groff has previously proposed the idea of a “triptych” of novels, of which Matrix and Vaster Wilds would be the first two parts. “The third one is killing me, actually — I’m dying, it’s murdering me in my sleep at night,” she told NPR’s Andrew Limbong in 2023. To be clear, Brawler is not that third novel; it is instead Groff’s third short story collection, and her first since Florida, a 2018 National Book Award finalist. The new collection’s nine stories paint the world in vivid hues, as seen from the angle of a high school swimmer, a mother, an heir, among others. But also, here’s hoping, at least for Groff’s sake, that her work on that other, unfinished novel has moved past the ol’ “murdering me” phase.

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Alabama5 days ago

Alabama5 days agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old boy dies in BMX accident, officials, Steel Wheels BMX says

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump unveils new rendering of sprawling White House ballroom project

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Mysteries Set in American Small Towns

-

San Francisco, CA1 week ago

San Francisco, CA1 week agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Ohio7 days ago

Ohio7 days agoOhio town launching treasure hunt for $10K worth of gold, jewelry

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: We Tested Shark’s Viral Facial Device