Lifestyle

Must We Feel Shame Over Divorce?

My husband, in-laws and fogeys had all gathered in my mother and father’ formal lounge in Dallas that night for a type of intervention, hoping they might discuss me out of ending my marriage.

“I simply don’t perceive it. He took you to 5 international locations,” my mother-in-law stated. “Is that not sufficient?”

“He takes care of you,” my mom added. “He offers you the whole lot.”

I hung my head, staring on the floral swirls of the Persian rug beneath my toes.

My father-in-law prompt I used to be sad as a result of my husband was not a health care provider, as I’m, whereas my very own father puzzled if I had met another person.

Though my husband and I had been separated for months, my determination to undergo with ending our marriage got here throughout as outlandish to our households. I had anticipated pushback; divorce stays unusual amongst South Asians, even within the diaspora. A lady initiating it’s much more taboo. And ending a wedding on the grounds I used to be claiming — a scarcity of emotional intimacy — certainly struck my survivalist Pakistani immigrant mother and father and in-laws as nonsensical.

They got here from households that crossed the India-Pakistan border underneath the quilt of night time, abandoning properties and wealth, to ascertain themselves in a brand new nation. Couldn’t I study to reside with a considerably lackluster marriage?

Marriage, for them, served a utilitarian goal because the unit of stability that constructed a better society primarily based on commonalities of cultural group, spiritual sect and household backgrounds. Love was merely a lucky byproduct.

My husband and I belonged to the identical demographics, however love didn’t flourish within the three years we have been married. He tried planning unique holidays; at my behest, we tried counseling. We moved nearer to household. Little modified.

I desperately wanted a deeper connection that I had sought to forge inside our marriage, however it wasn’t there. It was a necessity that centered itself in my acutely aware consciousness as I began my residency in psychiatry and found myself to a better depth, and one which I may not proceed dwelling with unmet.

Over time, my mother and father had observed my disquietude inside the marriage, however they inspired me towards tolerance and gratitude. My husband took me touring, earned an honest dwelling and there was nothing egregious like bodily abuse happening, so I ought to have the ability to love him. My lack of ability to take action spoke solely of my very own failure, not of an inherent incompatibility between us.

In our collectivist tradition, the supply of my dissatisfaction appeared silly, and my pursuit of divorce self-indulgent. What mattered most was that I used to be reneging on a dedication, threatening my very own and their standing in our Desi group, and throwing my life away — all around the premise that my husband and I didn’t “join.”

“You’ll be returning all the jewellery they gave you,” my mom stated to me as my in-laws walked out. Nobody had satisfied me to alter my thoughts, and everybody was sad about it.

“You’re making the most important mistake of your life,” my father stated.

The final time I noticed him, my husband appeared proper into me and stated, “You don’t know the best way to be a spouse.”

A yr after my divorce, and regardless of the disgrace of marital ineptitude foisted upon me, I made a decision to place myself on the market once more. But amongst my Desi circles, individuals didn’t see me as fairly so marriageable the second time round.

Once I requested a buddy if she knew anybody who could be proper for me, she stated, “Even my buddies who haven’t been married earlier than can’t discover somebody.”

My mom, possible desirous to spare me from disappointment, tried to handle my expectations. “I fear he gained’t such as you as soon as he learns you’re divorced,” she would say a few potential match. Her recommendation was to let males know this scarlet letter up entrance but additionally discuss it as little as attainable, a closed chapter that needn’t be reopened.

On my first post-divorce dinner date, the person requested me for extra particulars of my marriage’s demise after our appetizer. “That’s it?” he stated, his puzzlement on the absence of drama bordering on disappointment. He then proceeded to share that he, too, was divorced, and regaled me with particulars about how he discovered his spouse dishonest on him at their five-star resort in Mexico on their honeymoon. We didn’t meet once more.

Then there was the previous acquaintance with whom I had reconnected, who stated, “I don’t thoughts,” granting me approval I hadn’t sought. “So long as you don’t write a memoir or one thing about it.”

There was the person I hadn’t spoken to earlier than assembly, so he didn’t know I used to be divorced. He was having fun with steak frites after I informed him, and he set down his fork, French fry hanging off one of many tines, and stated, “It might have been good if you happen to had informed me that sooner.” He requested for the examine shortly after, and I didn’t see him once more.

I attempted to resist my tradition’s insistence that I really feel ashamed of my divorce, however it wore on me. In my eyes, I had made a crucial, genuine selection. That selection deeply harm my ex-husband, his household and my household, however the absence of affection in my marriage harm me. But time after time, I used to be reminded that maybe it was impractical for me to suppose I may nurture something new the place one thing had as soon as died.

Till I met Mahmoud. The primary time he and I talked about my marriage, we didn’t say a lot in any respect. In response to the little I did share, he stated merely, kindly, “That will need to have been exhausting.”

We had met on Minder (Muslim Tinder — now known as Salams), however I remembered his identify from when he consulted me a few affected person six months earlier, whereas he remembered me from two years earlier than that once we shared an elevator experience within the hospital on our first day of residency. That day, he had caught my identify from my ID badge and requested one in every of his co-residents if she knew me; she did, and she or he let him know I used to be married.

Seeing my profile on a courting app years later caught him abruptly, however it didn’t preserve him from swiping proper. The following few occasions Mahmoud and I met, I by no means tried to erase three years of my life’s narrative to go well with his consolation as a result of the truth that I had been married by no means bothered him. Dialog with him was simple.

But the concept of marrying him wasn’t. Our connection — the shortage of which had appeared to others a frivolous motive to finish a wedding — was there. It was life giving. However I had been deemed an individual who didn’t know the best way to preserve a wedding alive.

“If you happen to go for it, don’t mess up once more,” my mom stated after I informed her about him. The disgrace of being divorced — of getting as soon as declared my marriage a failure — had taken root deep inside me in a approach I had not absolutely acknowledged. And so as soon as Mahmoud proposed, I declined. I had thought that divorce would free me from a decaying marriage, and it had, however it had additionally metastasized into an internalized stigma that was stopping me from permitting a brand new relationship to flourish.

On describing their determination to marry, individuals usually say, “When , ” or “Go together with your intestine.” I used to be not a type of individuals; I didn’t know, and my intestine was uneasy both approach. If I by no means remarried, I’d by no means must undergo divorce once more; but if I didn’t remarry, I’d lose the particular person I had come to like.

Regardless of my no, Mahmoud took his probabilities and caught round. And I took my probabilities and ultimately stated sure. This summer season, three years after we married, the 2 of us and our child daughter visited my previous medical college campus. At one level, we drove by my previous apartment, the place I had lived throughout my first marriage. Mahmoud slowed the automotive and requested if I needed to go searching. Once I hesitated, he assured me he can be positive ready for so long as I wanted.

I received out and appeared up on the fifth-floor Juliet balcony of my previous apartment, remembering the way it had lacked enough depth for me to comfortably sit on the market. Once I selected my very own house post-divorce, I made certain it had a beautiful balcony. After transferring in, I arrange a rocking chair and facet desk and would sit on the market almost each night, embracing my hard-fought peace.

Once I received again into the automotive after only some minutes, Mahmoud stated, “You don’t wish to keep longer?”

“No,” I stated. “I stayed lengthy sufficient.”

Lifestyle

Sean Combs apologizes for 'my actions in that video' that appeared to show an assault

Sean “Diddy” Combs is pictured at the CBS Radford Studio Center in 2018 in Los Angeles. On Sunday, Combs apologized for his actions in a video that appears to show him beating his former singing protege and girlfriend Cassie Ventura in a Los Angeles hotel in 2016.

Willy Sanjuan/Invision/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Willy Sanjuan/Invision/AP

Sean “Diddy” Combs is pictured at the CBS Radford Studio Center in 2018 in Los Angeles. On Sunday, Combs apologized for his actions in a video that appears to show him beating his former singing protege and girlfriend Cassie Ventura in a Los Angeles hotel in 2016.

Willy Sanjuan/Invision/AP

Hip-hop mogul Sean “Diddy” Combs issued an apology on Sunday, two days after the release of a video which appeared to show him beating then-girlfriend Cassie Ventura.

“It’s so difficult to reflect on the darkest times in your life, but sometimes you got to do that,” Combs says in a video posted to Instagram. “I was f—– up — I mean, I hit rock bottom — but I make no excuses.”

The video, which was obtained and published by CNN on Friday, allegedly shows Combs grabbing, throwing, kicking and dragging Ventura in a hotel hallway, and throwing an object at her.

CNN reported that the video was recorded at the now-closed InterContinental Hotel in Century City on March 5, 2016. Elements of it appear to match accusations of physical and sexual assault that Ventura made in a civil lawsuit she filed against Combs last year.

While NPR has not been able to verify the authenticity of the video, in his apology, Combs appeared to do so.

“I take full responsibility for my actions in that video,” Combs said. “I was disgusted then when I did it. I’m disgusted now. I went and I sought out professional help. I got into going to therapy, going to rehab. I had to ask God for his mercy and grace. I’m so sorry. But I’m committed to be a better man each and every day. I’m not asking for forgiveness. I’m truly sorry.”

Ventura reached a settlement with Combs for an undisclosed figure in November, one day after the lawsuit was filed.

After the settlement, one of Combs’ lawyers, Ben Brafman, issued a statement declaring Combs’ innocence. He told NPR: “Just so we’re clear, a decision to settle a lawsuit, especially in 2023, is in no way an admission of wrongdoing. Mr. Combs’ decision to settle the lawsuit does not in any way undermine his flat-out denial of the claims. He is happy they got to a mutual settlement and wishes Ms. Ventura the best.”

NPR’s request for comment from Combs’ attorney on Sunday was not immediately returned.

In a written statement provided to NPR on Friday afternoon, Ventura’s attorney, Douglas Wigdor, said: “The gut-wrenching video has only further confirmed the disturbing and predatory behavior of Mr. Combs. Words cannot express the courage and fortitude that Ms. Ventura has shown in coming forward to bring this to light.”

Wigdor did not immediately reply on Sunday to a request for comment on Combs’ Instagram post.

Combs faces several lawsuits from named and unnamed plaintiffs alleging assault, rape and other misconduct. In March, federal agents raided homes associated with Combs in Los Angeles and Miami in what authorities at the time referred to as “an ongoing investigation.”

On Saturday, the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office said it was aware of the video and while it found the images “extremely disturbing and difficult to watch,” if the incident occurred in 2016, “unfortunately we would be unable to charge as the conduct would have occurred beyond the timeline where a crime of assault can be prosecuted.”

The statement said that law enforcement has not presented a case against Combs for the attack depicted in the video, “but we encourage anyone who has been a victim or witness to a crime to report it to law enforcement or reach out to our office for support from our Bureau of Victims Services.”

NPR’s Anastasia Tsioulcas contributed to this report.

Lifestyle

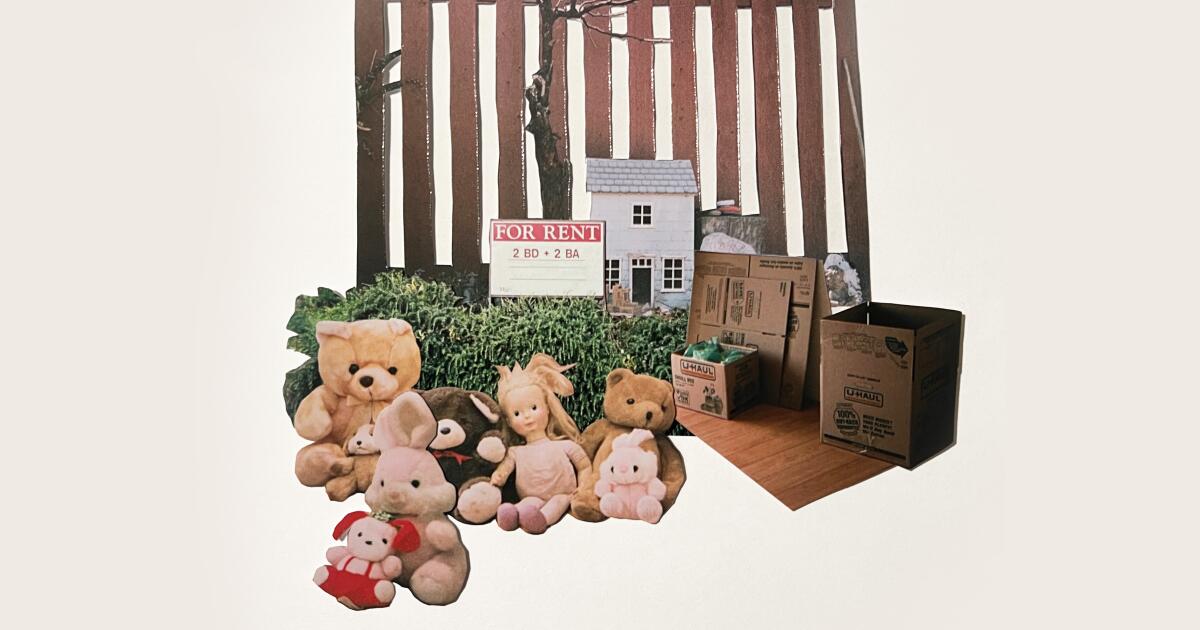

Renting used to be a source of shame to this apartment manager’s daughter. Now it’s a knowing comfort

I can barely remember a time when we didn’t live where we worked. Our first property manager job was for a 30-unit apartment building between Beverly Hills and Pico-Robertson. My parents didn’t speak English but got the job anyway because they knew a guy who knew a guy who knew a guy. There was an elementary school at the end of our magnolia tree-lined street that I couldn’t go to because the Beverly Hills School District allowed only Beverly Hills addresses. I would walk down the block to visit my friend (another apartment manager’s daughter) or to buy a sleeve of blue raspberry sour straws at the Blockbuster around the corner and hear children playing in the well-manicured school yard, but I never once saw an actual child. This was how I learned to perceive wealth in Los Angeles: near, but just out of reach.

Even at the age of 6 or 7 or 8, I knew that this was all temporary. Renting is inherently provisional, especially when you’re not actually paying rent. I made the most of it. While my mother cobbled together a career as a bookkeeper and my father assumed the role of both the maintenance guy and the manager of the building, I stole CDs from the mailroom, Rollerbladed in the slick oil-stained subterranean parking garage and belted Spice Girls lyrics in the emergency stairwell with my cousin until a tenant would open the door and find us there alone in the dark. I still own contraband from that time: someone’s copy of the “City of Angels” soundtrack. Inside our apartment, I shared a room with my parents. Our beds were butted up against each other, as they had always been.

Before this job and this building we lived in a one-bedroom apartment in West Hollywood with brown shag carpet and a cardboard box as my toy chest. The apartment buildings on our block, once favored by up-and-coming movie stars and writer Eve Babitz, now were occupied by Eastern Europeans fleeing the collapse of the Soviet Union. “There comes a moment for the immigrant’s child when you realize that you and your parents are assimilating at the same time,” writes Hua Hsu in his memoir, “Stay True.” While I attended preschool at Plummer Park, my mother went to community college and my father painted houses for $5 an hour. Before the brown shag carpet, we slept on my aunt’s couch in Mid-City for six months. And before the couch, we lived in a brutalist Soviet government-issued apartment in Minsk, Belarus. From the beginning, my life was steeped in the impermanence of renting, which mirrored the impermanence of our immigrant experience.

All immigrants are opportunists. Or, at least all the ones I’ve encountered. They are keenly aware of how, at any moment, everything can change. “Immigration, exile, being uprooted and made a pariah may be the most effective way yet devised to impress on an individual the arbitrary nature of his or her own existence,” writes Serbian poet Charles Simic. With each move, I felt the arbitrary nature of our existence. And every time I translated a 30-day notice or drafted a memo and slipped it under a tenant’s door, I felt the pull of my parents’ ambition. “We came here for you.” They’d say it often. Lovingly piling on the pressure until I could no longer see a future where I didn’t have something to prove.

My father found the second property manager job listing in a local newspaper. A 50-unit building in the affluent neighborhood of Westwood. He brought Mama and me along to the interview, although technically the managers were not supposed to have a child. I was told that if I was on my best behavior, I would go to the sought-after public elementary school down the street and finally get my own room. The front of the building was covered in a flash of fuchsia bougainvillea, and the surrounding brick towers glowed with inviting warm windows and hints of crystal chandeliers. The owners of the building were a wealthy elderly Germanic-Jewish couple who met us outside and assessed my potential with war-weary eyes. I looked up at them dutifully, every butterfly clip I owned fluttering on my head like a migration. “She’s a mini you,” the woman said, noticing the quiet stoicism I’d picked up from my father. She looked at us as if she were looking into her own immigrant past, her harrowing escape from Austria as a teenager during the Holocaust. She smiled. Bent down. And handed me the keys.

Los Angeles has been a haven for transplants and immigrants since the tail end of the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of the railroad. It was once advertised as a wellness paradise, the sanatorium capital of America, a temporary resort for turn-of-the-20th century tuberculosis patients eager to seek treatment in the form of sunshine and “fresh” air. Many of these patients got better and stayed. “Los Angeles, it should be understood, is not a mere city. On the contrary, it is, and has been since 1888, a commodity; something to be advertised and sold to the people of the United States like automobiles, cigarettes, and mouthwash,” writes Mike Davis in “City of Quartz.”

The commodification of Los Angeles and Hollywood, and the rising population, has made the city an expensive place to live. The majority of the population rents: According to a 2021 report, 63% of Los Angeles households are renter-occupied, while 37% are owner-occupied. And rent has more than doubled in the past decade, leading to an astonishing 57% of L.A. County residents being rent-burdened, meaning they spend a third or more of their income on rent. And yet people continue to move to Los Angeles, a place synonymous with liminal space — the space between who we are and who we want to become. Even if who you want to become is out of reach.

“If there is a predominant feeling in the city-state [Los Angeles], it is not loneliness or daze, but an uneasy temporariness, a sense of life’s impermanence: the tension of anticipation while so much quivers on the line,” writes Rosecrans Baldwin in “Everything Now: Lessons From the City-State of Los Angeles.”

Los Angeles is a city always on the edge of disaster: gentrification, housing shortages, unlawful evictions, homelessness (second largest homeless population outside of New York), greed, wildfire, earthquakes, floods, landslides, the imminent death of the legendary palm trees, the intangible but plausible possibility of breaking off from the continental United States and slipping into the Pacific Ocean. The city, like its residents, is impermanent, always shape-shifting, always on the verge of becoming something else.

“Our dwellings were designed for transience,” writes Kate Braverman about the midcentury West Los Angeles of her childhood in “Frantic Transmissions to and From Los Angeles: An Accidental Memoir.” “Apartments without dining rooms, as if anticipating a future where families disintegrated, compulsively dieted, or ate alone, in front of televisions.”

In Westwood, our living room was our dining room and our office. Leases were signed on the dinner table. At any moment, the phone or doorbell would ring with someone dropping off a rent check or complaining about a broken air conditioner or standing barefoot in a bathrobe locked out of their apartment. I would pretend to not care. I would eat my cheese puffs on the couch and stare attentively at the glowing TV, with the business of the building in my periphery. I would remind myself that this was temporary. Our liminal space. Maybe my parents would invest in an adult day care center like their friend Sasha? Maybe we would one day own a house? As I got older, I grew more ashamed. More aware of my own body and its presence. I would cower in my room or the hallway, shoveling Froot Loops into my mouth until the apartment was no longer an office but our home again. This shape-shifting was its own type of impermanence. One minute the apartment was a place where we lived and the next it was a place where we worked. The line was blurred and so was my idea of home. Of what is yours and what is mine.

Some of the tenants were there before us and some were a rotating cast of characters. But all of them were strangers we shared walls with. Of course, we weren’t the only immigrant family. There were also Persian immigrants who fled Iran during the Islamic Revolution, but they mostly kept to themselves. Due to the nature of the job, we were always on display. My parents’ accents. My growing body. My father’s health. The mezuzah on our door frame. Our apartment, a collection of discarded furniture from vacated units. Early on, I was warned to not make friends with any of the tenants. I was told it was unprofessional. A trap. That they only wanted to be my friend so they could get special treatment. Sometimes, we broke the rules. I babysat the child star while his single mother “networked” (partied in the Hollywood Hills). I played Marco Polo in the pool with the Persian kids. I leafed through headshots with a Russian mail-order bride while my parents drank tea with her mother. They would all eventually move out and so would we.

I used to tell my friends that we owned the building. That I would one day inherit it. This was easier than saying that we lived there because we worked there. I’m not sure if anyone believed me anyway. Many of my friends lived in what I considered to be mansions with nannies and parents with six-figure dual incomes that afforded them trips to faraway destinations I couldn’t place on a map. When my friends were over and the landline would ring, I would rush them to my bedroom before they could hear my father answer the phone with, “Manager.”

The only property my parents own is a shared plot at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. When my father was diagnosed with a chronic disease, my mother was left to manage the Westwood building on her own. Eventually, my parents retired after 21 years and moved out of the building during the first few months of the pandemic. They still rent, and so do I.

What is truly ours?

I’ve spent my life grappling with the concept of ownership. How our identity often gets wrapped up in what we own and what we don’t own. How in the U.S., ownership is the pinnacle of success. How there was no such thing as ownership in the failed Soviet experiment. How you could pick apples off any tree because they were there for everybody to enjoy. How owning a home in Los Angeles may forever be out of reach. How impermanent we are in the arbitrary nature of existence.

After I graduated from college and landed an office job in Los Angeles, I began renting apartments on my own. The eggshell walls painted over and over and over again. The rotating neighbors I still feared to befriend. The flying cockroaches. The broken laundry machines. The unabiding footsteps. The eternal sounds of other people’s lives. The possibility of moving out and starting all over again. It all felt so familiar. The impermanence I witnessed so often as a child was no longer a source of shame but a knowing comfort that at any moment everything could change.

Diana Ruzova is a writer from Los Angeles. She holds an MFA in literature and creative nonfiction from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Her writing has appeared in the Cut, Oprah Daily, Flaunt, Hyperallergic, Los Angeles Review of Books and elsewhere.

Lifestyle

Hold on to your wishes — there's a 'Spider in the Well'

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

Once upon a time, in the folkloric town of Bad Göodsburg, which is probably in Germany, there was an overworked newsboy.

Not only did he bring the people their daily news, he also swept their chimneys, shined their shoes, and brought them their milk.

He was overworked, and underappreciated.

So, when the townspeople discover that their wishing well is broken, the newsboy sets off to fix it — and get some revenge. Thus begins this children’s tale of extortion, labor rights, and justice.

Author and illustrator Jess Hannigan spoke about her debut picture book, Spider in the Well, with NPR’s Tamara Keith. Here are excerpts from that conversation, edited in parts for clarity and length.

Spider in the Well

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

hide caption

toggle caption

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

Spider in the Well

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

Interview highlights

Tamara Keith: How did you come to write a book about a spider, when I understand that you are afraid of spiders?

Jess Hannigan: I am. I don’t care for them. But do I love the webs they spin? Yes. Do I love the spooky aesthetic? Of course. Basically, the whole story came about because I really just had the image of looking down a well with the web, with the spider in it, and I thought that would look cool. And then I kind of asked myself, like, ‘Is there a story here? Why is he in there? What’s he catching in the web?’ And it kind of just wrote itself from there.

Keith: Is everyone in Bad Göodsburg a little bit bad and a little bit good? Or are all people a little bit bad and a little bit good?

Hannigan: Well it’s supposed to be, you know, real life. I really like when a character is in a gray area with some good and some bad because it’s realistic and relatable. And we have heroes and we have “villains,” but they’re just like us. And that way they’re humanized. And you just get to kind of discuss who you side with, who you agree with.

Keith: How would you describe what this book looks like?

Hannigan: I did the whole thing completely digitally. I kind of was going for a sort of imperfect printmaking effect because I love the look of block printing, but I don’t have the patience. So this was kind of a happy medium of me achieving that kind of folkloric, old-timey printing look without any of the labor.

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

Illustrations © 2024 Jess Hannigan

Keith: Where did you draw your inspiration for the art? The colors are not colors that you traditionally see in a children’s book. It’s like black and hot orange and purple.

Hannigan: A lot of my inspiration for the kind of shapes that I use comes from like, Polish posters. They’re from the 1960s and ’70s — Polish poster design was crazy and they had the wackiest shapes and colors, and I was introduced to those back in college.

These were just the colors that I had been obsessed with at the time that I happened to be making the book. They are like these kind of sickly, weird tones. And I used all those purples and greens for the “bad guys” because I guess it suited their vibe. But I’m actually colorblind, very slightly. So everyone’s been telling me this book is such a lovely shade of orange and I’ve been telling everyone it’s red.

Keith: What lesson do you want the kids who are reading this book — or who are reading it with their parents — what do you want them to take away from it?

Hannigan: I didn’t go into making this story with a lesson in mind. I know books with morals are important and they have a place for sure. But really I just wanted to make people laugh. And to go back and read it again and think, ‘What the heck was this guy even doing? Where did they learn how to do blackmail? Who taught them about extortion and labor rights and things?’

I love stories like that, that just make you wonder more about them.

Illustrations é 2024 Jess Hannigan

Illustrations é 2024 Jess Hannigan

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIndia Lok Sabha election 2024 Phase 4: Who votes and what’s at stake?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSkeletal remains found almost 40 years ago identified as woman who disappeared in 1968

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoUS Border Patrol agents come under fire in 'use of force' while working southern border

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBorrell: Spain, Ireland and others could recognise Palestine on 21 May

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTales from the trail: The blue states Trump eyes to turn red in November

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNorth Dakota gov, former presidential candidate Doug Burgum front and center at Trump New Jersey rally

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCatalans vote in crucial regional election for the separatist movement

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago“Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes”: Disney's New Kingdom is Far From Magical (Movie Review)