Lifestyle

Maureen Corrigan picks her favorite books from an 'unprecedented' 2024

“Unprecedented” surely was one of the most popular words of 2024 so it’s fitting that my best books list begins with an “unprecedented” occurrence: two novels by authors who happen to be married to each other.

James by Percival Everett

James, by Percival Everett, reimagines Huckleberry Finn told from the point of view of Jim, Huck’s enslaved companion on that immortal raft ride. Admittedly, the strategy of thrusting a so-called supporting character into the spotlight of a reimagined classic has been done so often, it can feel a little tired. So, when is a literary gimmick, not a gimmick? When the reimagining is so inspired it becomes an essential companion piece to the original novel. Such is the power of James.

Alternating mordant humor with horror, Everett makes readers understand that for Jim — here, accorded the dignity of the name James — the Mississippi may offer a temporary haven, but, given the odds of him making it to freedom, the river will likely be “a vast highway to a scary nowhere.”

Colored Television by Danzy Senna

Percival Everett is married to Danzy Senna, whose novel, Colored Television, is a revelatory satire on race and class. Senna’s main character, Jane, is a mixed-race writer and college teacher struggling to finish her second novel. Desperate for money, Jane cons her way into meeting a Hollywood producer who’s cooking up a bi-racial situation comedy. Senna’s writing is droll and fearless. Listen to Jane’s thoughts about teaching:

One of the worst parts of teaching was how, like a series of mini strokes, it ruined you as a writer. A brain could handle only so many undergraduate stories about date rape and eating disorders, dead grandmothers and mystical dogs.

Long Island by Colm Tóibín

Long Island is Colm Tóibín’s sequel to his 2009 bestseller, Brooklyn, whose main character, Eilis Lacey, is now trapped in a marriage and a neighborhood as stifling as the Irish town she fled. Abruptly, Eilis decides to visit her 80 year old mother back in Ireland, a place she hasn’t returned to in almost two decades, with good reason. There she’ll discover, much as another Long Islander named Jay Gatsby once did, that you can’t repeat the past. Tóibín floats with ease between time periods in the space of a sentence, but it’s his omissions and restraint, the words he doesn’t write, that make him such an astute chronicler of this working-class, Catholic, pre-therapeutic world where people never speak directly about anything, especially feelings.

Tell Me Everything by Elizabeth Strout

Tell Me Everything reunites readers with the by now familiar characters who populate Elizabeth Strout’s singular novels, among them: writer Lucy Barton, lawyer Bob Burgess and retired teacher Olive Kitteridge — all living in Maine. Nobody nails the soft melancholy of the human condition like Strout — and that’s a phrase she would never write because her style is so understated. Lucy and Olive like to get together to share stories of “unrecorded” lives. At the end of one of these sessions, Olive exclaims:

“I don’t know what the point is to this story!”

“People,” Lucy said quietly, leaning back. “People and the lives they lead. That’s the point.”

“Exactly.” Olive nodded.

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

Martyr! is Iranian American poet Kaveh Akbar’s debut novel about a young man named Cyrus Shams struggling with depression and the death of his mother, who was a passenger on Iran Air Flight 655, an actual plane that was mistakenly shot down in 1988 by an actual Navy ship, the USS Vincennes. All 290 passengers on board that plane were killed. Early in the novel, Cyrus articulates his need to understand his mother’s death and those of other “martyrs” — accidental or deliberate — throughout history. Akbar’s tone here is unexpectedly comic, his story antic, and his vision utterly original.

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake is a literary spy novel wrapped up tight in the soiled plastic wrap of noir. Kushner’s main character, a young woman who goes by the name of Sadie Smith, is a former FBI agent turned freelance spy who infiltrates a radical farming collective in France that’s suspected of sabotaging nearby agribusinesses. You don’t read Kushner for the “relatability” of her characters; instead, it’s her dead-on language and orange-threat-alert atmosphere that draw readers in.

Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford

In Cahokia Jazz, Francis Spufford summons up a femme fatale, crooked cops and politicians, and working-class resentment as bitter as bathtub gin. He weds these hardboiled elements to an eerie story about the actual vanished city of Cahokia, which, before the arrival of Columbus, was the largest urban center north of Mexico. Spufford’s novel is set in an alternative America of 1922 where the peace of Cahokia’s Indigenous, white, and African American populations is threatened by a grisly murder.

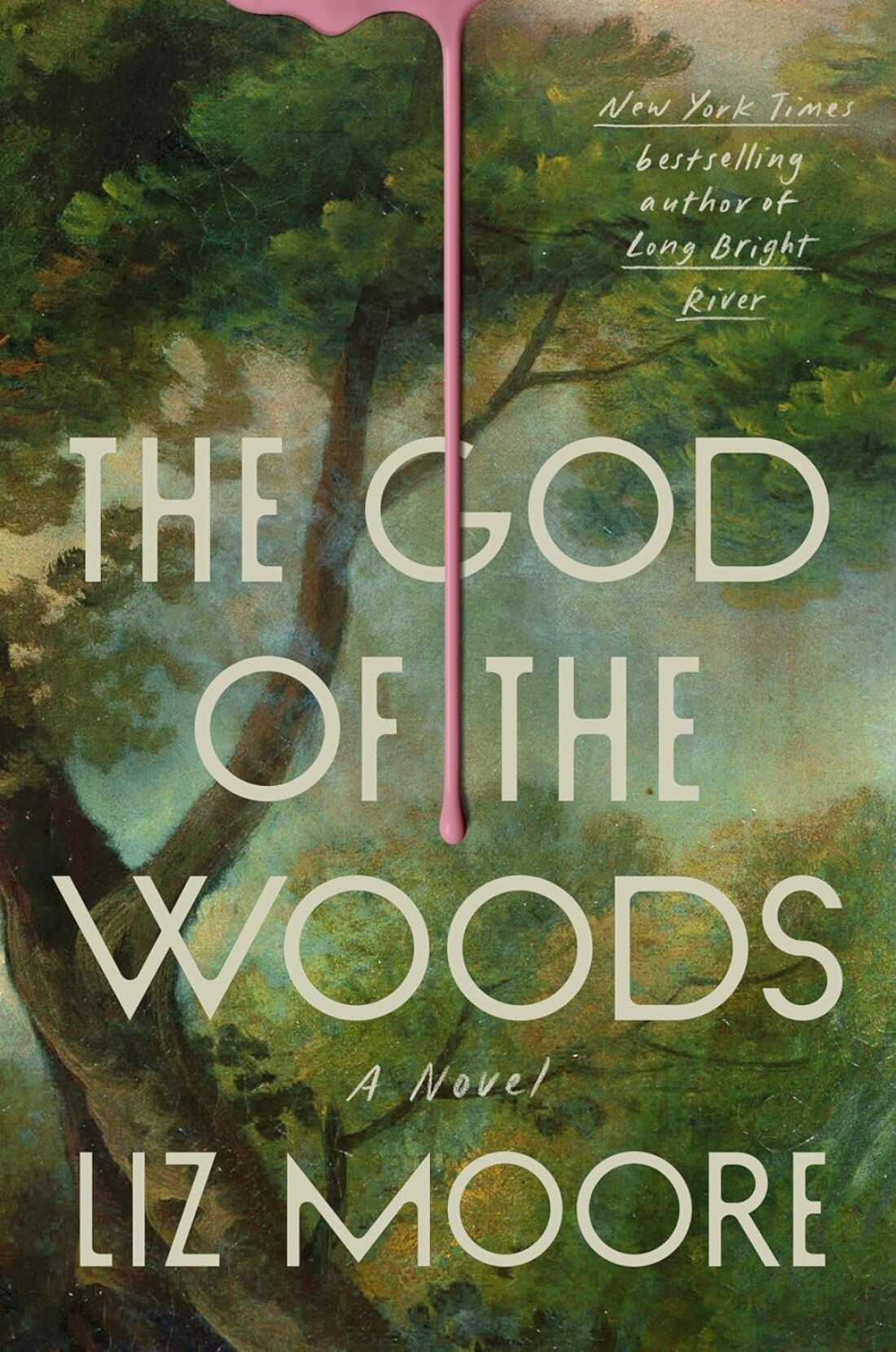

The God of the Woods by Liz Moore

There’s a touch of Gothic excess about Liz Moore’s suspense novel The God of the Woods, beginning with the plot premise that not one, but two children from the wealthy Van Laar family disappear from the same camp in the Adirondacks some 14 years apart. Moore’s previous book, Long Bright River, was a superb novel about the opioid crisis in Philadelphia; The God of the Woods is something stranger and unforgettable.

A Wilder Shore by Camille Peri

I’ve thought about A Wilder Shore — Camille Peri’s biography of the “bohemian marriage” of Fanny and Robert Louis Stevenson — ever since reading it this summer. In her “Introduction” Peri says something that’s also haunted me. She describes her book as: “an intimate window into how [the Stevensons] lived and loved — a story that is at once a travel adventure, a journey into the literary creative process, and, I hope, an inspiration for anyone seeking a freer, more unconventional life.” That it is.

The Letters of Emily Dickinson edited by Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell

This list began with the word “unprecedented” and I’ll end it with an “unprecedented” voice — that of Emily Dickinson. A monumental collection of The Letters of Emily Dickinson was published this year. Edited by Dickinson scholars Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell, it’s the closest thing we’ll probably ever have to an autobiography by the poet. Here’s a thank-you note Dickinson wrote in the 1860s to her beloved sister-in-law:

Dear Sue,

The Supper was delicate and strange. I ate it with compunction as I would eat a Vision.

1,304 letters are collected here and, still, they’re not enough.

Happy Holidays; Happy Reading!

Books We Love includes 350+ recommended titles from 2024. Click here to check out this year’s titles, or browse nearly 4,000 books from the last 12 years.

Lifestyle

After years of avoiding the ER, Noah Wyle feels ‘right at home’ in ‘The Pitt’

Wyle, who spent 11 seasons on ER, returns to the hospital in The Pitt. Now in Season 2, the HBO series has earned praise for its depiction of the medical field. Originally broadcast April 21, 2025.

Hear The Original Interview

Television

After years of avoiding the ER, Noah Wyle feels ‘right at home’ in ‘The Pitt’

Lifestyle

TMZ Streaming Live, Come Into Our Newsroom and Watch Things Happen!

TMZ Live Stream

Come Into Our Office and Watch News Happen!!!

Published

We want you to be a part of TMZ, so every weekday, between 9:30 AM and 11:30 AM PT, we take you inside our newsroom via live stream.

You never know what you’re gonna get … a big story that breaks, an argument erupts in the room, or someone’s just joking around.

Your comments are a big part of the stream, and the staff spends a lot of time speaking directly to you. Every day is different!

We also use our live stream to produce our “TMZ Live” TV show.

Lifestyle

Doctors says ‘The Pitt’ reflects the gritty realities of medicine today

From left: Noah Wyle plays Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch, the senior attending physician, and Fiona Dourif plays Dr. Cassie McKay, a third-year resident, in a fictional Pittsburgh emergency department in the HBO Max series The Pitt.

Warrick Page/HBO Max

hide caption

toggle caption

Warrick Page/HBO Max

The first five minutes of the new season of The Pitt instantly capture the state of medicine in the mid-2020s: a hectic emergency department waiting room; a sign warning that aggressive behavior will not be tolerated; a memorial plaque for victims of a mass shooting; and a patient with large Ziploc bags filled to the brink with various supplements and homeopathic remedies.

Scenes from the new installment feel almost too recognizable to many doctors.

The return of the critically acclaimed medical drama streaming on HBO Max offers viewers a surprisingly realistic view of how doctors practice medicine in an age of political division, institutional mistrust and the corporatization of health care.

Each season covers one day in the kinetic, understaffed emergency department of a fictional Pittsburgh hospital, with each episode spanning a single hour of a 15-hour shift. That means there’s no time for romantic plots or far-fetched storylines that typically dominate medical dramas.

Instead, the fast-paced show takes viewers into the real world of the ER, complete with a firehose of medical jargon and the day-to-day struggles of those on the frontlines of the American health care system. It’s a microcosm of medicine — and of a fragmented United States.

Many doctors and health professionals praised season one of the series, and ER docs even invited the show’s star Noah Wyle to their annual conference in September.

So what do doctors think of the new season? As a medical student myself, I appreciated the dig at the “July effect” — the long-held belief that the quality of care decreases in July when newbie doctors start residency — rebranded “first week in July syndrome” by one of the characters.

That insider wink sets the tone for a season that Dr. Alok Patel, a pediatrician at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, says is on point. Patel, who co-hosts the show’s companion podcast, watched the first nine episodes of the new installment and spoke to NPR about his first impressions.

To me, as a medical student, the first few scenes of the new season are pretty striking, and they resemble what modern-day emergency medicine looks and sounds like. From your point of view, how accurate is it?

I’ll say off the bat, when it comes to capturing the full essence of practicing health care — the highs, the lows and the frustrations — The Pitt is by far the most medically accurate show that I think has ever been created. And I’m not the only one to share that opinion. I hear that a lot from my colleagues.

OK, but is every shift really that chaotic?

I mean, obviously, it’s television. And I know a lot of ER doctors who watch the show and are like, “Hey, it’s really good, but not every shift is that crazy.” I’m like, “Come on, relax. It’s TV. You’ve got to take a little bit of liberties.”

As in its last season, The Pitt sheds light on the real — sometimes boring — bureaucratic burdens doctors deal with that often get in the way of good medicine. How does that resonate with real doctors?

There are so many topics that affect patient care that are not glorified. And so The Pitt did this really artful job of inserting these topics with the right characters and the right relatable scenarios. I don’t want to give anything away, but there’s a pretty relatable issue in season two with medical bills.

Right. Insurance seems to take center stage at times this season — almost as a character itself — which seems apt for this moment when many Americans are facing a sharp rise in costs. But these mundane — yet heartbreaking — moments don’t usually make their way into medical dramas, right?

I guarantee when people see this, they’re going to nod their head because they know someone who has been affected by a huge hospital bill.

If you’re going to tell a story about an emergency department that is being led by these compassionate health care workers doing everything they can for patients, you’ve got to make sure you insert all of health care into it.

As the characters juggle multiple patients each hour, a familiar motif returns: medical providers grappling with some heavy burdens outside of work.

Yeah, the reality is that if you’re working a busy shift and you have things happening in your personal life, the line between personal life and professional life gets blurred and people have moments.

The Pitt highlights that and it shows that doctors are real people. Nurses are actual human beings. And sometimes things happen, and it spills out into the workplace. It’s time we take a step back and not only recognize it, but also appreciate what people are dealing with.

2025 was another tough year for doctors. Many had to continue to battle misinformation while simultaneously practicing medicine. How does medical misinformation fit into season two?

I wouldn’t say it’s just mistrust of medicine. I mean that theme definitely shows up in The Pitt, but people are also just confused. They don’t know where to get their information from. They don’t know who to trust. They don’t know what the right decision is.

There’s one specific scene in season two that, again, no spoilers here, but involves somebody getting their information from social media. And that again is a very real theme.

In recent years, physical and verbal abuse of healthcare workers has risen, fueling mental health struggles among providers. The Pitt was praised for diving into this reality. Does it return this season?

The new season of The Pitt still has some of that tension between patients and health care professionals — and sometimes it’s completely projected or misdirected. People are frustrated, they get pissed off when they can’t see a doctor in time and they may act out.

The characters who get physically attacked in The Pitt just brush it off. That whole concept of having to suppress this aggression and then the frustration that there’s not enough protection for health care workers, that’s a very real issue.

A new attending physician, Dr. Baran Al-Hashimi, joins the cast this season. Sepideh Moafi plays her, and she works closely with the veteran attending physician, Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch, played by Noah Wyle. What are your — and Robby’s — first impressions of her?

Right off the bat in the first episode, people get to meet this brilliant firecracker. Dr. Al-Hashimi, versus Dr. Robby, almost represents two generations of attending physicians. They’re almost on two sides of this coin, and there’s a little bit of clashing.

Sepideh Moafi, fourth from left, as Dr. Baran Al-Hashimi, the new attending physician, huddles with her team around a patient in a fictional Pittsburgh teaching hospital in the HBO Max series The Pitt.

Warrick Page/HBO Max

hide caption

toggle caption

Warrick Page/HBO Max

Part of that clash is her clear-eyed take on artificial intelligence and its role in medicine. And she thinks AI can help doctors document what’s happening with patients — also called charting — right?

Yep, Dr. Al-Hashimi is an advocate for AI tools in the ER because, I swear to God, they make health care workers’ lives more efficient. They make things such as charting faster, which is a theme that shows up in season two.

But then Dr. Robby gives a very interesting rebuttal to the widespread use of AI. The worry is that if we put AI tools everywhere, then all of a sudden, the financial arm of health care would say, “Cool, now you can double how many patients you see. We will not give you any more resources, but with these AI tools, you can generate more money for the system.”

The new installment also continues to touch on the growing corporatization of medicine. In season one we saw how Dr. Robby and his staff were being pushed to see more patients.

Yes, it really helps the audience understand the kind of stressors that people are dealing with while they’re just trying to take care of patients.

In the first season, when Dr. Robby kind of had that back and forth with the hospital administrator, doctors were immediately won over because that is such a big point of frustration — such a massive barrier.

There are so many more themes explored this season. What else should viewers look forward to?

I’m really excited for viewers to dive into the character development. It’s so reflective of how it really goes in residency. So much happens between your first year and second year of residency — not only in terms of your medical skill, but also in terms of your development as a person.

I think what’s also really fascinating is that The Pitt has life lessons buried in every episode. Sometimes you catch it immediately, sometimes it’s at the end, sometimes you catch it when you watch it again.

But it represents so much of humanity because humanity doesn’t get put on hold when you get sick — you just go to the hospital with your full self. And so every episode — every patient scenario — there is a lesson to learn.

Michal Ruprecht is a Stanford Global Health Media Fellow and a fourth-year medical student.

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX4 days ago

Dallas, TX4 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska2 days ago

Nebraska2 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoSpotify digs in on podcasts with new Hollywood studios