Lifestyle

How to tour a haunting Santa Barbara estate that's been frozen in time for half a century

The house, a French palace on a Santa Barbara bluff, stands as undisturbed as a crime scene, a pair of unstrung harps in the music room, china laid out on the dinner table, waves crashing on East Beach below.

This is the mansion that heiress Huguette Clark left behind — well, one of them. For half a century, as Clark (1906-2011) paid an estimated $40,000 per month to keep it unchanged, the coveted estate known as Bellosguardo remained no livelier than the cemetery next door.

A tour group waits to enter Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

But now outsiders trickle in. For the last year and a half, the Bellosguardo Foundation has been quietly offering ground-floor tours for $100 a head, and it may soon open up more of the long-idle estate to visitors.

For anyone fascinated by great estates, robber barons, generational wealth or just human psychology, the tour is a chance to see territory that’s been off-limits for decades. It’s also a haunting illustration of what money can buy and what it can’t.

“We used to come to the cemetery and peek over the wall,” confessed Patti Gibbs, a longtime Santa Barbara resident who was among those on hand for the 10 a.m. tour one recent Wednesday.

“I’ve been waiting for them to let me in since I read the book years ago,” said visitor Peggy Simmons of Ojai.

The book she mentioned is “Empty Mansions,” by Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr., which lays out the history of the Clarks and their homes in California, New York and Connecticut.

But stepping into the story is different from reading it. With docents Susan Bush and Cindy McClelland leading the way, Gibbs, Simmons and a handful of other visitors entered the front door.

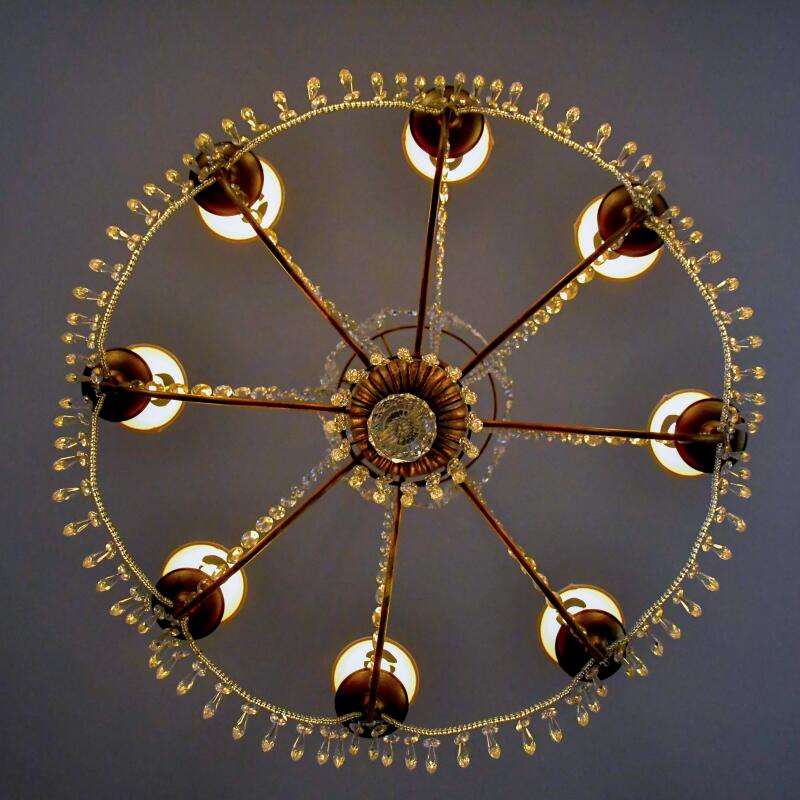

The dining room, set with dinnerware. One of many custom chandeliers — this one hangs in the mansion’s art studio. A portrait in the estate shows heiress Huguette Clark, who died in 2011 at age 104. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

The music room of the estate.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

They examined the telephone room to the left, then the coat room to the right (with a portrait of a French World War I hero on the wall) and the Steinway piano at the foot of the spiral staircase. And they listened closely as the docents addressed the morning’s central questions:

Where did the money come from? And why did Huguette Clark put the mansion on pause?

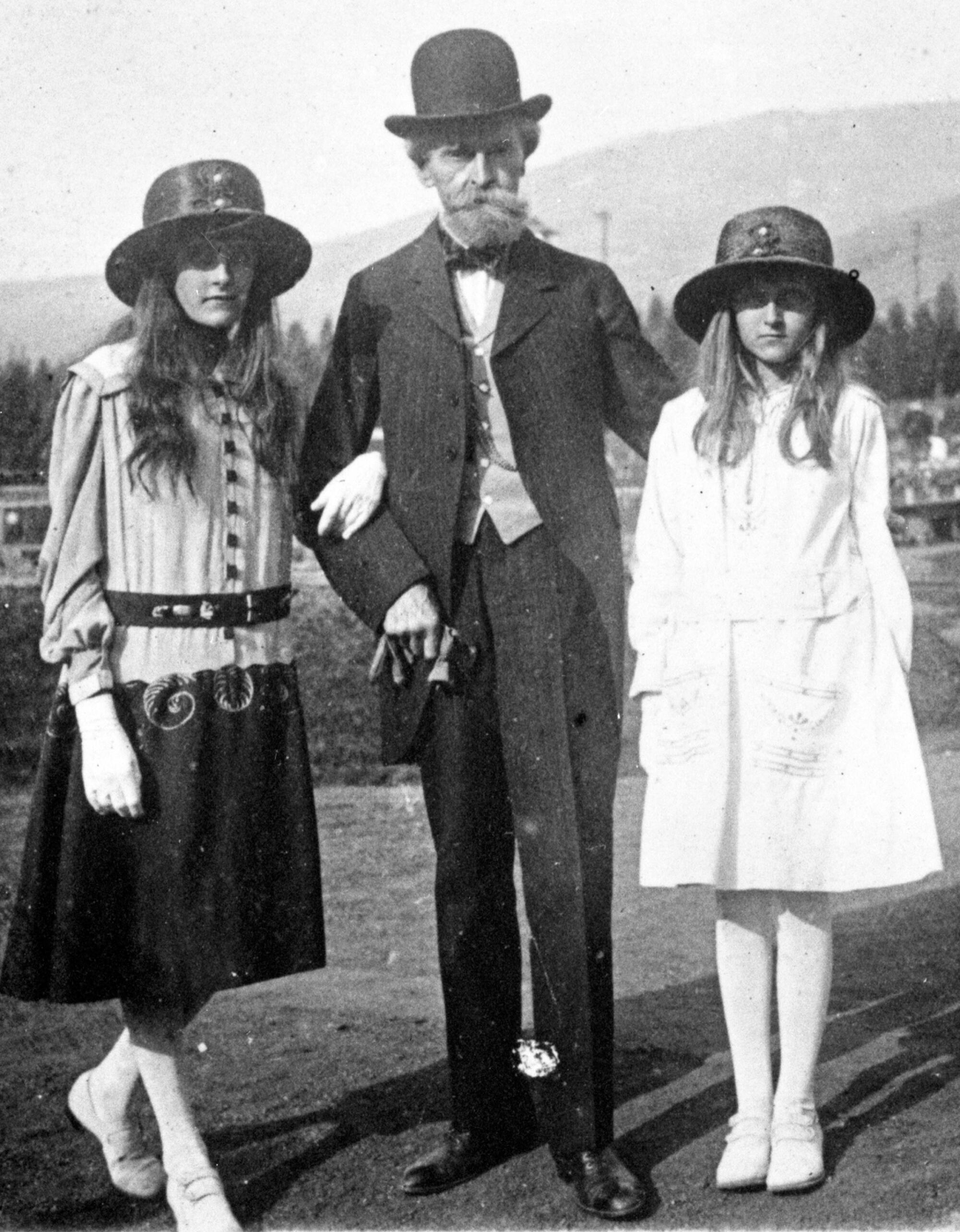

The first answer is copper, mined, sold and leveraged by a slight, bearded man named William Andrews Clark.

Clark (1839-1925), born in a Pennsylvania log cabin, got rich in copper mining and built his first mansion in Butte, Mont. Later he built a railroad from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City, opened banks, mined more copper in Arizona, co-founded Las Vegas (seat of Clark County) and built another mansion, a 121-room behemoth on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. (It has since been razed.)

Clark and daughters Andrée, left, and Huguette visit Columbia Gardens, which he built in Butte, Mont. It was about 1917.

(Montana Historical Society)

“He’s one of the richest men that nobody’s ever heard of,” McClelland told the visitors.

Along the way Clark got married, fathered seven children, lost his first wife to typhoid fever, remarried in his 60s and fathered two additional daughters. He also got caught bribing Montana state legislators, yet served a term as U.S. senator from that state. And his name does endure here and there.

His son, William Andrews Clark Jr., made the donations that started UCLA’s William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. Also, you could say the senior Clark inspired Mark Twain.

Clark, Twain wrote, “is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a ball and chain on his legs.”

Much of the Bellosguardo story, however, is about the next generation of Clarks. As the group advanced through the house, admiring custom chandeliers and golden bathroom fixtures, the docents pushed the narrative forward.

A custom-made chandelier dangles in the library of the Bellosguardo Estate in Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

By summer 1923, when Clark and his second wife, Anna, arrived as renters at this 23-acre property above East Beach, he was one of the world’s wealthiest men. But he was in his mid-80s, 39 years older than Anna. Four years earlier, the couple had lost their older daughter, 16-year-old Andrée, to meningitis. Their surviving daughter, Huguette Clark, was now 17.

The Santa Barbara summer went well. By year’s end, the Clarks had bought the place for $300,000. But less than two years later, Clark died, leaving Anna and Huguette with a chunk of his fortune, the Santa Barbara property and the Italianiate villa that stood upon it, nicknamed Bellosguardo, or Pretty View.

So why, then, do visitors today walk through a French palace and not an Italian villa?

Because in 1933, as the country struggled with the Great Depression, Anna and Huguette Clark decided to level the villa (which had been damaged by a 1925 earthquake) and start over. Since they had lived several years in Paris and often spoke French to each other, they liked the idea of something French — a notable change from the Spanish Colonial projects popping up all over Santa Barbara.

Architect Reginald D. Johnson, designer of the Biltmore hotel in Montecito, delivered a rigorously symmetrical gray stone building (including one door that opens to nowhere) that paid minimal attention to ocean views. Two stories, 27 rooms, 13 fireplaces.

A sculpture in Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate shows Andrée Clark, a daughter of copper mogul William Andrews Clark who died in her teens. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate include an art studio full of paintings by and of heiress Huguette Clark, who is seen in the work on the easel. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Grounds, Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

It’s subdued, but not dull. As visitors see, there’s a circular women’s powder room. Carved maple panels line walls in one room, while 160 carved oak panels dominate another. The building wraps around a stately pond, much of the furniture dates to the 18th century and the walls are hung with paintings of the French countryside and, in just about every room, portraits of Andrée and Huguette as doe-eyed girls.

“Reminds me of Hearst Castle,” said visitor Cherie Visconti, eyeing the dining room.

On the library shelves, Voltaire and George Eliot are joined by Agatha Christie and Erle Stanley Gardner, the Ventura lawyer and author who created Perry Mason.

The Clarks never lived here full time. By the foundation’s estimation, the mother and daughter made 14 visits (by train) between 1936 and 1953, staying about 18 months in all.

On those stays, Huguette, known for being shy but smart, played piano and violin, collected dolls and painted, including many portraits and still lives now hanging under the high ceilings of the mansion’s art studio. Having been married and quickly divorced in her 20s, Huguette didn’t date much.

Anna, an accomplished musician, played the harp and sponsored a string quartet (whom she outfitted with Stradivarius instruments).

Dining room, Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Portraits in the Music room of Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate include a piano-top photograph of heiress Huguette Clark. She is also shown in the oil painting in the background. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

But by 1953, Anna Clark’s health had become too delicate for the train ride west, and Huguette stayed east as well. After Anna Clark died in 1963, Huguette, now in her 50s, continued to stay away. Later, she said that Bellosguardo held so many reminders of her absent mother that it made her sad. But not sad enough to let it go.

Now without her sister, father, mother, partner or a job, Huguette kept more to herself. She took pleasure in commissioning dolls and dollhouses, sending gifts to artisans, employees and their children. She checked photographs to make sure that staffers were keeping Bellosguardo unchanged, from the doghouse (whose occupant had died years before) to the 1933 Cadillac limousine and Chrysler convertible in the garage.

Then, one day in 1991, after a long spell without medical care, she summoned a doctor to her 42-room New York apartment (which was really three apartments combined). He arrived to find a wraith in her 80s, down to 75 pounds, suffering from multiple cancers that had disfigured her face.

Yet she survived. Once Huguette had been transported to a New York hospital, she responded well to surgeries. Choosing to remain in the hospital and rejecting all suggestions that she move home, she regained her health and lasted until her death more than 20 years, shortly before her 105th birthday.

For all those years, she not only left Bellosguardo empty but also a Connecticut mansion and the Manhattan apartment. From her hospital room, she bought more dolls, commissioned dollhouses, bid at auctions and rebuffed hospital officials when they pressed too often for donations. Meanwhile, she traded calls and letters with friends and employees, showering gifts on her favorites.

Grounds, Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Over those last 20 years, authors Dedman and Newell write, Huguette spent an estimated $30 million on gifts (including six homes) for her day nurse, Hadassah Peri, who routinely worked seven-day weeks.

In many respects, they wrote, the Clark family saga is a classic folk tale — “except told in reverse, with the bags full of gold arriving at the beginning, the handsome prince fleeing and the king’s daughter locking herself away in the tower.”

The fighting over her estate persisted for years (she left two wills). In time, the Bellosguardo Foundation was created to operate the Santa Barbara mansion as an arts center. To some degree, this is par for the course in the neighborhood. Casa del Herrero in nearby Montecito has been hosting visitors for years, as has Lotusland, renowned for its gardens. But years passed before the first Bellosguardo tours happened, a delay that sparked complaints from some in Santa Barbara.

Now, the foundation director and docents say, an expansion of the tours is at hand.

Foundation Executive Director Jeremy Lindaman estimated that 100 to 150 people take tours each week. Others visit as part of occasional special events, such as a flamenco dance presentation that took place on the grounds last month during Santa Barbara’s Old Spanish Days Fiesta.

Bellosguardo tours

What: 90-minute tours led by a volunteer docent. Visitors must be at least 14, and no indoor photography is allowed.

When: Usually offered Wednesdays through Sundays, two or three per day.

Where: Bellosguardo, 1407 E. Cabrillo Blvd., Santa Barbara

Cost: $100

Info: For details and to sign up to be notified of tour openings, visit the Bellosguardo Foundation website

By late fall, Lindaman said, he’s hoping to add a second tour that covers the mansion’s more intimate quarters, including bedrooms and service areas. A coffee-table book is in the works, as well.

“Everything that was here when she died is still here,” Lindaman said.

But booking a tour is a two-step exercise. Instead of offering direct booking through the Bellosguardo website, the foundation asks would-be visitors to sign up for notification. Every two months, an email goes out and tour slots fill quickly.

Thanks in part to this process and the price, Bellosguardo remains a well-kept half-secret. For many in Santa Barbara, the family’s most visible legacy is not the mansion but the Andrée Clark Bird Refuge, a 42-area city park and lagoon just north of Bellosguardo, that Huguette Clark paid to create and maintain in her sister’s name.

Yet among those who get inside Bellosguardo’s gates, Huguette Clark and her family are still sparking speculation.

Walking the rooms, “You just feel that family,” said Penny Simmons. “Sad things happened around here.”

“I didn’t know she was such a fine artist,” Patti Gibbs said at the end of her tour.

“We think she lived the life she wanted to live,” said her docent guide, McClelland.

“She was not crazy,” said Peter Higgins of Oxnard. “She knew what she was doing right up until the end.”

Lifestyle

After years of avoiding the ER, Noah Wyle feels ‘right at home’ in ‘The Pitt’

Wyle, who spent 11 seasons on ER, returns to the hospital in The Pitt. Now in Season 2, the HBO series has earned praise for its depiction of the medical field. Originally broadcast April 21, 2025.

Hear The Original Interview

Television

After years of avoiding the ER, Noah Wyle feels ‘right at home’ in ‘The Pitt’

Lifestyle

TMZ Streaming Live, Come Into Our Newsroom and Watch Things Happen!

TMZ Live Stream

Come Into Our Office and Watch News Happen!!!

Published

We want you to be a part of TMZ, so every weekday, between 9:30 AM and 11:30 AM PT, we take you inside our newsroom via live stream.

You never know what you’re gonna get … a big story that breaks, an argument erupts in the room, or someone’s just joking around.

Your comments are a big part of the stream, and the staff spends a lot of time speaking directly to you. Every day is different!

We also use our live stream to produce our “TMZ Live” TV show.

Lifestyle

Doctors says ‘The Pitt’ reflects the gritty realities of medicine today

From left: Noah Wyle plays Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch, the senior attending physician, and Fiona Dourif plays Dr. Cassie McKay, a third-year resident, in a fictional Pittsburgh emergency department in the HBO Max series The Pitt.

Warrick Page/HBO Max

hide caption

toggle caption

Warrick Page/HBO Max

The first five minutes of the new season of The Pitt instantly capture the state of medicine in the mid-2020s: a hectic emergency department waiting room; a sign warning that aggressive behavior will not be tolerated; a memorial plaque for victims of a mass shooting; and a patient with large Ziploc bags filled to the brink with various supplements and homeopathic remedies.

Scenes from the new installment feel almost too recognizable to many doctors.

The return of the critically acclaimed medical drama streaming on HBO Max offers viewers a surprisingly realistic view of how doctors practice medicine in an age of political division, institutional mistrust and the corporatization of health care.

Each season covers one day in the kinetic, understaffed emergency department of a fictional Pittsburgh hospital, with each episode spanning a single hour of a 15-hour shift. That means there’s no time for romantic plots or far-fetched storylines that typically dominate medical dramas.

Instead, the fast-paced show takes viewers into the real world of the ER, complete with a firehose of medical jargon and the day-to-day struggles of those on the frontlines of the American health care system. It’s a microcosm of medicine — and of a fragmented United States.

Many doctors and health professionals praised season one of the series, and ER docs even invited the show’s star Noah Wyle to their annual conference in September.

So what do doctors think of the new season? As a medical student myself, I appreciated the dig at the “July effect” — the long-held belief that the quality of care decreases in July when newbie doctors start residency — rebranded “first week in July syndrome” by one of the characters.

That insider wink sets the tone for a season that Dr. Alok Patel, a pediatrician at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, says is on point. Patel, who co-hosts the show’s companion podcast, watched the first nine episodes of the new installment and spoke to NPR about his first impressions.

To me, as a medical student, the first few scenes of the new season are pretty striking, and they resemble what modern-day emergency medicine looks and sounds like. From your point of view, how accurate is it?

I’ll say off the bat, when it comes to capturing the full essence of practicing health care — the highs, the lows and the frustrations — The Pitt is by far the most medically accurate show that I think has ever been created. And I’m not the only one to share that opinion. I hear that a lot from my colleagues.

OK, but is every shift really that chaotic?

I mean, obviously, it’s television. And I know a lot of ER doctors who watch the show and are like, “Hey, it’s really good, but not every shift is that crazy.” I’m like, “Come on, relax. It’s TV. You’ve got to take a little bit of liberties.”

As in its last season, The Pitt sheds light on the real — sometimes boring — bureaucratic burdens doctors deal with that often get in the way of good medicine. How does that resonate with real doctors?

There are so many topics that affect patient care that are not glorified. And so The Pitt did this really artful job of inserting these topics with the right characters and the right relatable scenarios. I don’t want to give anything away, but there’s a pretty relatable issue in season two with medical bills.

Right. Insurance seems to take center stage at times this season — almost as a character itself — which seems apt for this moment when many Americans are facing a sharp rise in costs. But these mundane — yet heartbreaking — moments don’t usually make their way into medical dramas, right?

I guarantee when people see this, they’re going to nod their head because they know someone who has been affected by a huge hospital bill.

If you’re going to tell a story about an emergency department that is being led by these compassionate health care workers doing everything they can for patients, you’ve got to make sure you insert all of health care into it.

As the characters juggle multiple patients each hour, a familiar motif returns: medical providers grappling with some heavy burdens outside of work.

Yeah, the reality is that if you’re working a busy shift and you have things happening in your personal life, the line between personal life and professional life gets blurred and people have moments.

The Pitt highlights that and it shows that doctors are real people. Nurses are actual human beings. And sometimes things happen, and it spills out into the workplace. It’s time we take a step back and not only recognize it, but also appreciate what people are dealing with.

2025 was another tough year for doctors. Many had to continue to battle misinformation while simultaneously practicing medicine. How does medical misinformation fit into season two?

I wouldn’t say it’s just mistrust of medicine. I mean that theme definitely shows up in The Pitt, but people are also just confused. They don’t know where to get their information from. They don’t know who to trust. They don’t know what the right decision is.

There’s one specific scene in season two that, again, no spoilers here, but involves somebody getting their information from social media. And that again is a very real theme.

In recent years, physical and verbal abuse of healthcare workers has risen, fueling mental health struggles among providers. The Pitt was praised for diving into this reality. Does it return this season?

The new season of The Pitt still has some of that tension between patients and health care professionals — and sometimes it’s completely projected or misdirected. People are frustrated, they get pissed off when they can’t see a doctor in time and they may act out.

The characters who get physically attacked in The Pitt just brush it off. That whole concept of having to suppress this aggression and then the frustration that there’s not enough protection for health care workers, that’s a very real issue.

A new attending physician, Dr. Baran Al-Hashimi, joins the cast this season. Sepideh Moafi plays her, and she works closely with the veteran attending physician, Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch, played by Noah Wyle. What are your — and Robby’s — first impressions of her?

Right off the bat in the first episode, people get to meet this brilliant firecracker. Dr. Al-Hashimi, versus Dr. Robby, almost represents two generations of attending physicians. They’re almost on two sides of this coin, and there’s a little bit of clashing.

Sepideh Moafi, fourth from left, as Dr. Baran Al-Hashimi, the new attending physician, huddles with her team around a patient in a fictional Pittsburgh teaching hospital in the HBO Max series The Pitt.

Warrick Page/HBO Max

hide caption

toggle caption

Warrick Page/HBO Max

Part of that clash is her clear-eyed take on artificial intelligence and its role in medicine. And she thinks AI can help doctors document what’s happening with patients — also called charting — right?

Yep, Dr. Al-Hashimi is an advocate for AI tools in the ER because, I swear to God, they make health care workers’ lives more efficient. They make things such as charting faster, which is a theme that shows up in season two.

But then Dr. Robby gives a very interesting rebuttal to the widespread use of AI. The worry is that if we put AI tools everywhere, then all of a sudden, the financial arm of health care would say, “Cool, now you can double how many patients you see. We will not give you any more resources, but with these AI tools, you can generate more money for the system.”

The new installment also continues to touch on the growing corporatization of medicine. In season one we saw how Dr. Robby and his staff were being pushed to see more patients.

Yes, it really helps the audience understand the kind of stressors that people are dealing with while they’re just trying to take care of patients.

In the first season, when Dr. Robby kind of had that back and forth with the hospital administrator, doctors were immediately won over because that is such a big point of frustration — such a massive barrier.

There are so many more themes explored this season. What else should viewers look forward to?

I’m really excited for viewers to dive into the character development. It’s so reflective of how it really goes in residency. So much happens between your first year and second year of residency — not only in terms of your medical skill, but also in terms of your development as a person.

I think what’s also really fascinating is that The Pitt has life lessons buried in every episode. Sometimes you catch it immediately, sometimes it’s at the end, sometimes you catch it when you watch it again.

But it represents so much of humanity because humanity doesn’t get put on hold when you get sick — you just go to the hospital with your full self. And so every episode — every patient scenario — there is a lesson to learn.

Michal Ruprecht is a Stanford Global Health Media Fellow and a fourth-year medical student.

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX5 days ago

Dallas, TX5 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Missouri3 days ago

Missouri3 days agoDamon Wilson II, Missouri DE in legal dispute with Georgia, to re-enter transfer portal: Source