Lifestyle

‘Dawson’s Creek’ star James Van Der Beek has died at 48

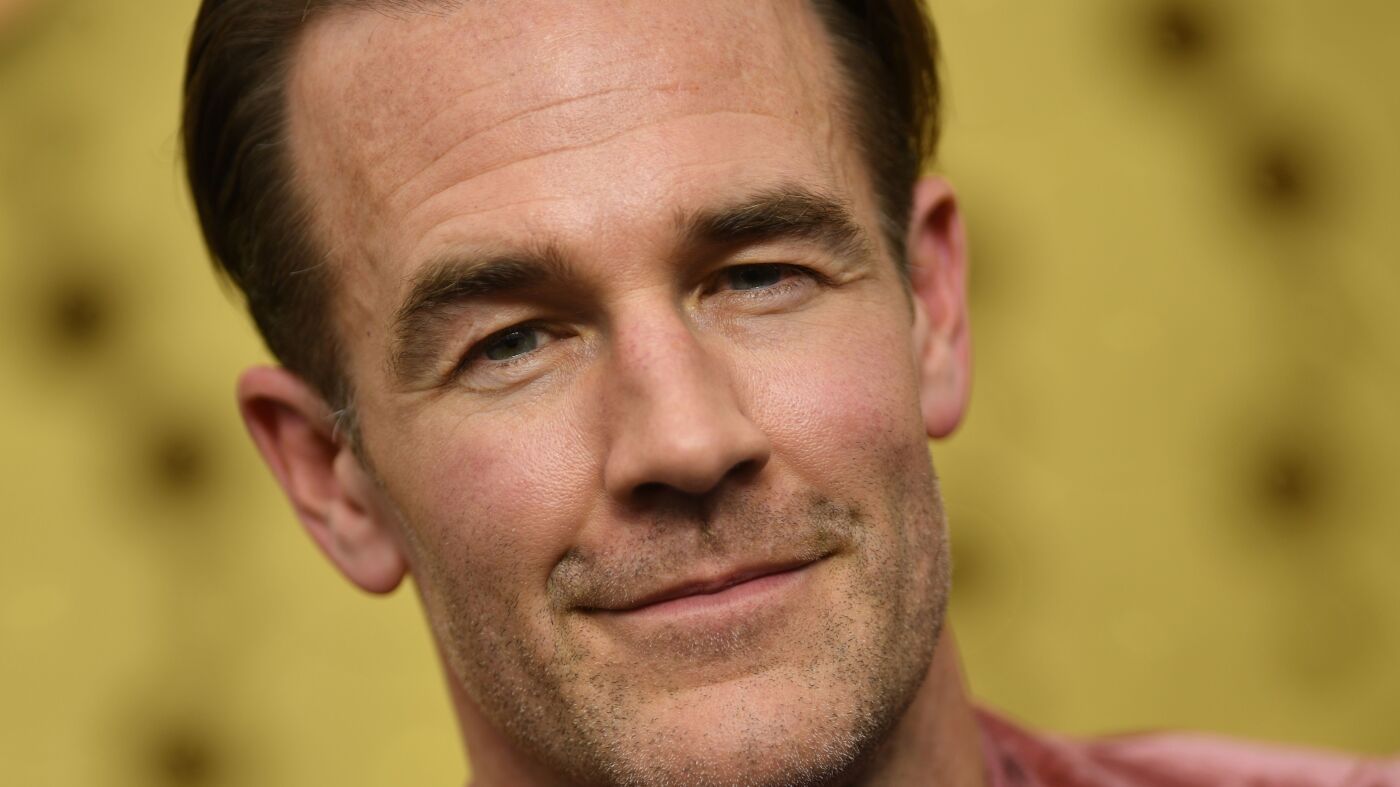

Actor James Van Der Beek arriving at the Emmy Awards in 2019.

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

James Van Der Beek — best known for his role as Dawson Leery in the hit late 1990s and early aughts show Dawson’s Creek — has died. He was 48. Van Der Beek announced his diagnosis of Stage 3 colon cancer in November 2024.

His family wrote on Instagram on Wednesday, “Our beloved James David Van Der Beek passed peacefully this morning. He met his final days with courage, faith, and grace. There is much to share regarding his wishes, love for humanity and the sacredness of time. Those days will come. For now we ask for peaceful privacy as we grieve our loving husband, father, son, brother, and friend.”

Van Der Beek started acting when he was 13 in Cheshire, Conn., after a football injury kept him off the field. He played the lead in a school production of Grease, got involved with local theater, and fell in love with performing. A few years later, he and his mother went to New York City to sign the then-16 year old actor with an agent.

But Van Der Beek didn’t break out as a star until he was 21, when he landed the lead role of 15-year-old Dawson Leery, an aspiring filmmaker, in Dawson’s Creek.

Van Der Beek’s life changed forever with this role. The teen coming-of-age show was a huge hit, with millions of weekly viewers over 6 seasons. It helped both establish the fledgling WB network and the boom of teen-centered dramas, says Lori Bindig Yousman, a media professor at Sacred Heart University and the author of Dawson’s Creek: A Critical Understanding.

“Dawson’s really came on the scene and felt different, looked different,” Bindig Yousman says.

It was different, she points out, from other popular teen shows at the time such as Beverly Hills, 90210. “It wasn’t these rich kids. It was supposed to be normal kids, but they were a little bit more intelligent and aware of the world around them … It was attainable in some way. It was reflective.”

The Dawson’s drama centered around love, hardships, relationships, school and sex — sometimes pushing the boundaries when it came to teens discussing sex. Van Der Beek’s character Dawson was a moody, earnest dreamer, sometimes so earnest he came across as a “sad sack,” says Bindig Yousman. He had a seasons long on-again off-again on-screen relationship with his best friend Joey, played by Katie Holmes. Bindig Yousman says Van Der Beek quickly became seen as a heartthrob.

“I think he was very safe for a lot of tweens, and that’s when we started to get the tween marketing,” she says, referring to the attention paid to him by magazines like Teen People and Teen Celebrity. “And so because he wasn’t a bad guy, he was conventionally attractive … He definitely appealed to the masses.”

Dawson’s Creek launched the careers of not just of James Van Der Beek, but his costars Katie Holmes, Joshua Jackson and Michelle Williams. All went on to have successful careers in the entertainment industry.

Despite his success, Van Der Beek didn’t land many roles that rose to that same level of fame he enjoyed in Dawson’s Creek. Perhaps because audiences associated him so much with Dawson Leery, it was difficult to separate him from that character.

Still, he starred in the 1999 coming of age film Varsity Blues, as a high school football player who wants to be more than just a jock. In 2002’s Rules of Attraction, he played a toxic college drug dealer.

And he actually parodied himself in the sitcom Don’t Trust the B—- in Apartment 23. In it, he’s a self-obsessed actor unsuccessfully trying to get people to see him as someone other than the celebrity from Dawson’s Creek. In an episode where he decides to teach an acting class, the students ignore the lesson and instead pester him to perform a monologue from the show.

In real life as well, the floppy blond-haired Dawson Leery is the one that stole fans’ hearts, but Bindig Yousman says Van Der Beek still enjoyed a strong fanbase that followed him to other shows, even when they were only smaller cameos.

In the 2024 Instagram post about his cancer, Van Der Beek said “Each year, approximately 2 billion people around the world receive this diagnosis … I am one of them.” (There were about 18.5 million new cases of cancer around the world in 2023, a number that researchers say is projected to rise.) Van Der Beek leaves behind six children.

The cast of Dawson’s Creek reunited to raise money for the nonprofit F Cancer, which focuses on prevention, detection and support for people affected by cancer. They read the pilot episode at a Broadway theater in New York City in September 2025. His former co-star Michelle Williams organized the reunion. James Van Der Beek was unable to perform, due to his illness, but contributed an emotional video that was shown onstage. In it, he thanked his crew and castmates, and the Dawson’s Creek fans for being “the best fans in the world.”

Lifestyle

What Did Valentines Day Cards Look Like 200 Years Ago?

In the late 19th century, few things telegraphed yearning like a card adorned with paper lace, gold foil and a couple exchanging a coy glance.

Today, such a card would evoke an eye roll.

The evolution of cards from the treacly confections of Victorian England to the quippy missives of today reflect both shifting design aesthetics and broader cultural customs around romance. As the borders of socially accepted relationships have shifted, so have the cards. Where once there was poetry, now there are drawings of pizzas.

“Greeting cards are a reflection of society,” said Carlos Llansó, executive director of the Greeting Card Association, a trade organization that represents roughly 4,000 independent card makers.

Valentine’s Day cards today are less formal, precious and prescribed, Mr. Llansó said, because our understanding of love has become more expansive.

Lottery and lace

Historians struggle to trace the exact origins of Valentine’s Day — some pinpoint the holiday to a curiously unromantic Pagan festival in Rome that involved goat slaughter and nudity — but they tend to agree that its association with romance was most likely established in England.

Early Valentine’s Day celebrations, dating as far back as the 17th century, were only loosely associated with love and often revolved around a lottery, said Sally Holloway, a cultural historian at the University of Warwick whose research focuses on love, marriage and courtship in 18th century England.

People would pull names out of a hat and select someone to be their Valentine from February through Easter.

“Your Valentine could be your neighbor, it could be a colleague, it could be a member of your family,” Dr. Holloway said. “You’d pin the name of the person who you’d been given as your Valentine to your clothes.” Matched pairs would exchange gifts, dance together and maybe write funny riddles or poems for each other.

A confluence of rapid social changes in the late 1700s and early 1800s, including the idealization of marrying for love rather than for economic advantage, Dr. Holloway said, helped to transform Valentine’s Day into a commercialized celebration of romantic love with a partner of your choosing.

Click on an image to look at the details.

This period dovetailed with the advent of new printing technologies and mass production, as well as an expansion of postal services, making Valentine’s Day cards a popular component of courtship rituals.

They presented, in many ways, a rare opportunity to directly convey desire within the confines of an otherwise buttoned-up Victorian society, where bold romantic declarations could be both risky and risqué. At the time, the responsibility of pursuing a marriage partner fell to men, and women tended to avoid overtly signaling affection.

But on Valentine’s Day, those rules were flipped.

“For one day a year, the language of love became the preserve of women,” Dr. Holloway said. And because it was considered a daring and even racy act to send a Valentine’s Day card, women “couldn’t put their name to it,” Dr. Holloway said. It is why so many cards from that era contain only vague, brief greetings, sometimes with a question mark at the end, adding a whiff of mystique.

The custom arrived in the United States in the mid-1800s, and crafty, entrepreneurial women fueled its commercialization.

Esther Howland — often referred to as the “mother of the American valentine” — is said to have first received a Valentine’s Day card from someone in Britain in 1847 and was inspired to create her own version.

“It was her idea to essentially create an assembly line of women putting together these really complex Valentines,” said Jamie Kwan, an assistant curator at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. The cards were handmade, and Howland “imported materials from the U.K. and Germany to incorporate into these cards.”

Estimates suggest she sold between $75,000 and $100,000 worth of cards a year, roughly the equivalent of $3 million today.

Embracing new ideas of love

Over time, innovation around the craftsmanship of cards slowed, and it was their imagery that began to reflect a rapidly changing culture.

In 1910, Hallmark entered the industry and quickly became one of the largest and most recognizable card makers. The brand’s earliest Valentine’s Day cards relied heavily on the Victorian symbols of love from the previous century: hearts, Cupids and lovebirds.

By the 1930s, Hallmark started printing cards with boundary-pushing images of couples embracing and, by 1945, dancing.

“It used to be that we used a lot more traditional forms of creative crafts, like engraving, calligraphy and lace,” said Jen Walker, a vice president of Hallmark’s creative studios. Eventually, consumers found those aesthetic details less enticing.

“We are a consumer led brand — so we followed the consumer and what their needs were,” she added.

But Hallmark cards did not display Black couples until 1970, and the company did not introduce Valentine’s Day cards for those in same-sex relationships until 2008.

‘There isn’t even a heart on it’

In the mid 2000s, Valentine’s Day cards went through another major shift.

In 2013, Emily McDowell, a writer, product consultant and business adviser, designed a Valentine’s Day card to better reflect some of the difficult-to-categorize situationships she had been in.

The card had no illustrations. It was plain and white with text on the front that read: “I know we’re not, like, together or anything but it felt weird to just not say anything so I got you this card. It’s not a big deal. It doesn’t really mean anything. There isn’t even a heart on it. So basically it’s a card saying hi. Forget it.”

She put it up on Etsy, anticipating that only a handful of people would buy it.

Within days, she sold thousands, she said, and had to stop accepting new orders. The success prompted her to quit her job in advertising and start her namesake brand. The next year, she released another card that also instantly became a hit. It read: “There’s no one I’d rather lie in bed and look at my phone next to.”

Over the past 13 years, the company has sold millions of similarly witty cards. (Ms. McDowell left the company in 2022, and it was acquired by Hachette Publishing last year.) While Ms. McDowell’s early designs feel commonplace now, they were among the first in an industrywide move away from the stilted, saccharine Valentine’s Day cards of previous decades.

Many independent card designers today, Mr. Llansó explained, continue to tap into a consumer demand for plain-speaking, authentic cards. As a result, some of the more popular designs feature references to the state of the world. Others nod to cultural iconography, like Labubus or the enduring appeal of sweatpants. Not all of them are intended for romantic partners, and many can be used in other kinds of relationships.

Mitzi Sampson, the founder of the card company Mitzi Bitsy Spider, said her best-selling card was one that featured a grinning raccoon holding up a sign reading “you are TRASH to me.”

Ms. Sampson said she designed that card in 2023 for her sister “because she loves raccoons and because I love her.”

That, she added, is exactly what consumers want now. Not frills or grand proclamations, but an intimate knowledge of the receiver and “the simple recognition that says I know you, I see you, I choose you.”

Lifestyle

FBI Investigates Possible Vehicle of Interest in Nancy Guthrie Search

Nancy Guthrie Search

Feds Investigate Potential Vehicle of Interest

Published

Federal agents in Arizona may have snagged another crucial lead in the search for Nancy Guthrie … because cops were seen poking around a potential vehicle of interest at a Tucson restaurant near her home Friday night.

Around 11 PM local time Friday, reporters spotted a swarm of FBI agents and Pima County Sheriff’s deputies descending on a home near East Orange Grove Road and North First Avenue … but that wasn’t the only hotspot, as investigators were also zeroed in on a nearby Culver’s where a silver Range Rover SUV appeared to be a key focus.

VIDEO: FBI and PCSD officials covering Range Rover and apparent investigation continues. pic.twitter.com/Vm4weqJx2C

— KGUN 9 (@kgun9) February 14, 2026

@kgun9

According to online videos, law enforcement investigated the vehicle and eventually towed it away. Sources tell Fox News Digital one man was detained following a traffic stop involving the vehicle and confirmed the stop is connected to a search warrant served at a home near Nancy Guthrie’s house.

It’s unclear what investigators are specifically searching for within the vehicle, since they have taken measures to cover their inspection from the cameras with a yellow sheet. It’s worth noting this Culver’s location is just 2 miles away from the confirmed activity tied to the Nancy Guthrie investigation.

#BREAKING – FBI on scene at a Culver’s, very close to the scene related to the Nancy Guthrie investigation. We are still working to see if there’s any connection. Pima County deputies and Marana Police are here. One man has been detained here at the scene pic.twitter.com/S4fZlJGtpq

— Nick Ciletti (@NickCiletti) February 14, 2026

@NickCiletti

Fox News is reporting that at least three people have been detained Friday evening in connection with the investigation into the disappearance of Nancy Guthrie, according to a local law enforcement source.

A resident told News 4 Tucson that she witnessed three people being detained during this SWAT operation, and according to an unconfirmed report by a neighbor and outlets at the scene, another person had shot himself in the head during the interaction.

When we asked the Pima County Sheriff PIO about this detail, their response was “We cannot confirm anything at this time” — adhering to the FBI’s request to refrain from commenting further on the joint investigation.

NewsNation

As we previously reported, NewsNation‘s Brian Entin first reported that their crew got the video of cops walking out with a man and woman from a home which is about 2 miles from Nancy’s. There are reportedly about 2 dozen officers on the scene … including FBI agents.

While authorities are staying mum on confirming any details, reporters on the scene are covering this operation bit-by-bit.

Story developing …

Lifestyle

When Posting Becomes Its Own Style of Politics

A growing number of conservative influencers are making content in which they claim to uncover fraud.

In December, the YouTuber Nick Shirley uploaded a video purporting to expose a scheme led by Somali refugees in Minneapolis.

It caught the attention of Vice President JD Vance, who shared the video online. Soon after, ICE was deployed to the city.

The video was inspiring to Amy Reichert, a 58-year-old San Diego resident, who started making her own videos claiming a similar scheme was afoot in her city.

She is one of many creators channeling populist rage and elite resentment into a style of posting.

It’s a mode of practicing politics some are calling “slopulism.”

Ms. Reichert doesn’t like to call herself a right-wing influencer.

She has a sizable following on social media (some 60,000 followers on X, and 80,000 on Instagram), where she posts videos of herself talking about what in her view is corruption in the Democratic-leaning city government of San Diego, usually while wearing rose-tinted aviator sunglasses.

Since the beginning of this year, Ms. Reichert, a licensed private investigator, has been making content that highlights what she thinks is a pattern of taxpayer fraud in her city’s child care centers. It’s a pivot she has made since watching the video by Mr. Shirley, the 23-year-old MAGA YouTuber, in which he claimed to have uncovered widespread fraud by a network of Somali Americans operating child care centers.

“I thought, How can I, as a private investigator and private citizen, do what Nick did in Minnesota?” Ms. Reichert said. “We are drowning in fraud in California.”

After just a few hours of researching state databases in early January, Ms. Reichert began to post screenshots on X of documents she claimed belonged to “ghost” day care centers in San Diego County. The posts spread widely. Soon, she was on television to discuss her work with the Fox News host Jesse Watters, and President Trump was sharing a clip of the segment on his Truth Social platform.

Then Ms. Reichert began making videos, sometimes standing outside the day care centers in question, in which she repeated the allegations while presenting little proof of wrongdoing. But her message — that foul play was taking place — was clear.

One video Ms. Reichert posted was quickly clipped and reshared on X by right-wing news aggregators. It earned close to half a million views — essentially a viral moment for a creator of Ms. Reichert’s stature.

She was also happy to see that Mr. Shirley, whose work Mr. Vance suggested was more consequential than Pulitzer Prize-winning journalism, began to follow Ms. Reichert on X.

“Quite amazing, these past few weeks,” Ms. Reichert said.

Ms. Reichert is one among many conservative content creators who have become the internet’s busiest sleuths in recent weeks. They create videos that are light on evidence and traditional journalistic techniques but are filled with sinister-sounding claims that neatly align with the Trump administration’s priorities.

Armed with digital cameras and publicly available documents, they claim to be documenting patterns of elite corruption, taxpayer fraud, abuse of power and government waste across the country, hoping their posts and videos will cross into the feeds of elected officials, as Mr. Shirley’s did.

Some of the biggest names in MAGA media have fanned out across the country to make this content.

The influencer Cam Higby claimed to have uncovered a nearly identical case of fraud, undertaken once again by Somali migrants, in Washington State.

Benny Johnson, a creator with close ties to the Trump administration, set out looking for fraud within state-run homeless programs and misspent Covid relief funds in California.

On YouTube, Tyler Oliveira, a 26-year-old creator with over eight million subscribers, posted videos claiming to have uncovered a “welfare-addicted” township in upstate New York.

Even Dr. Mehmet Oz, a Trump administration official, has made a video in which he claims a $3.5 billion medical fraud operation is happening in Los Angeles.

What Is ‘Slopulism,’ Exactly?

It’s a novel form of political behavior that has left many political commentators and researchers struggling to articulate what it is. Though many are quick to say what it’s not: investigative journalism. It is also, experts say, more than misinformation or disinformation, terms that fail to capture the nature of these misleading posts and how they are filtering up into the highest echelons of government.

Curt Mills, the executive director of The American Conservative magazine, called it “MAGA-muzak.”

Kate Starbird, a researcher at the University of Washington who studies online spaces and extreme politics, has called it “participatory propaganda.”

“Try ‘entrepreneurial opportunism,’” said A.J. Bauer, an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Alabama with a focus on right-wing groups.

“The real novelty here is the synchronization between the movement, the party and the state — but there isn’t a buzzword yet,” Mr. Bauer added.

The sameness of this politicized content, created overwhelmingly by figures orbiting the conservative cultural ecosystem, is, to many on the right and the left, not unlike digital “slop.” The term, which refers to low-quality, low-information, A.I.-generated content, has gradually expanded to more generally describe the gruel-like mixture of online ideas, images and memes flooding our feeds.

That’s how you get another term, “slopulism,” which has of late become a buzzword with X users and Substackers, many associated with the right, during the course of Trump’s second term.

Slopulism, as described by these commentators, is a kind of political post that elides concrete political concerns in favor of the fast-acting satisfactions of social media rage and culture-war jargon. It’s a political tendency that offers followers emotional gratification through mindless, performative gestures online.

Many of the content creators, like Ms. Reichert, were unfamiliar with the terms slop or slopulism.

These days, on platforms like X, slopulism is a pejorative label often applied to posts by politicians and pundits alike, anyone who shares out lowest-common-denominator ideas designed to appeal to loyal political bases.

On the right, this can look like gleeful cruelty, sadistic memes, posts that “own the libs” or sensationalized claims about fraud and conspiracy. On the left, it could be social justice messaging, online identity politics or populist economic proposals to, say, tax the rich.

The new wave of fraud-themed content, made by creators like Mr. Shirley, invokes familiar themes of populist rage and elite resentment. It seems to be the latest evolution in a culture where posting is a primary method of practicing politics — except these posts appear to be made not only to get in on a trending wave, but also to provoke policy action.

“Slopulism works by harnessing the excitement and vibe of a moment,” said Neema Parvini, a senior fellow at the University of Buckingham in England who is considered to have popularized the term. He believes it’s a way for populist leaders, like Mr. Trump, to keep their bases content.

“It convinces supporters to invest their emotions in story lines rather than the substantive politics or structure behind it,” he said. “It doesn’t lead anywhere, it’s just entertainment.”

‘Building for Years’

Renaming the Gulf of Mexico. The annexation of Greenland. A proposal to turn Gaza into a glittering resort town. All of these ideas found their potency in the form of viral content, circulated by those on the right, before they were fully embraced by the Trump administration. The online right podcaster Alex Kaschuta called this “the vibes-based international order.”

“This dynamic has been building for years,” said Dr. Starbird, the extremism researcher. “But in the second Trump administration, this relationship is more direct, with policies clearly being motivated, shaped and justified by and through digital content creation.”

As with most viral content, the ideas emerging from these online environs can be fleeting. Mr. Mills, of The American Conservative, described the administration’s recent policy priorities as having a “flavor of the month” feel.

Some on the right pushed back against the idea that slopulism, or any dynamic like it, is driving the administration’s actions.

“It’s a misread of the situation,” said Jesse Arm, vice president of external affairs at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank. He pointed out that something like the Greenland annexation, which is often described as meme policy, could be traced to “far more serious conversations” between the president and his advisers as far back as 2019.

“I don’t think President Trump is hyper-invested in what’s happening online,” he said. “His administration is paying attention to what happens online, sure, but only in the sense that this is the main arena to gauge policy discourse.”

In a statement, Abigail Jackson, a White House spokeswoman, said Mr. Trump “always receives feedback and input from a variety of sources before making a decision that is in the best interest of the American people.”

Some see this as a positive style of governance, Mr. Mills said, adding, “It’s hyper-democratic in some ways: ‘Let’s look online and see what’s popular.’”

The content can have political consequences, but Mr. Bauer, the University of Alabama journalism professor, said he did not view its creation as a sincere political effort. Many of the creators he has observed making these videos aren’t highly ideological figures or even MAGA die-hards.

“They see an opportunity,” he said. “These are people that aspire to be famous online. They see that there’s a lot of desire and demand for right-wing content. And they are motivated by things like money and attention.”

Ms. Reichert said that the amount of money generated from her posts was “pathetically low,” but declined to offer further details.

Most of the fraud videos published in recent weeks resemble Mr. Shirley’s in both form and content. Almost always, the person suspected of wrongdoing is an immigrant or a member of a minority group, the most common ethnic category being that of Somali refugees, as in Mr. Shirley’s video about Minnesota.

While some, like Ms. Reichert, say they are inspired by Mr. Shirley, others deny any influence.

Until this January, David Khait, a conservative content creator with over 100,000 subscribers on YouTube, posted mostly man-on-the-street debates and interviews, a confrontational content style popularized by the conservative activist Charlie Kirk, who was assassinated in September. But recently, he has begun making videos about what he says is voter fraud in Fulton County, Georgia.

“There’s been no pivot here,” Mr. Khait, 26, wrote in a text message. “Call my content what it is: confronting institutional failure head-on because that’s what’s staring Americans in the face.”

The slopulist impulse may be most acute on the right at the moment — owing to the Republican control of the federal government — but some have argued this mode of online political engagement has its origins across the aisle.

Sean Monahan, the founder of the trend forecasting group K-Hole, has traced it back to the rise of the so-called “dirtbag left,” an online set of leftists who came to prominence during Bernie Sanders’s presidential run in 2016.

“It was a style of politics presented to younger, left-wing consumers, things like raising taxes on billionaires or modern monetary theory or controls on rent,” Mr. Monahan said. “There was a presumption that you could lay out a policy goal with no political trade-offs, no constituencies to navigate and no downsides.”

One recent example of slopulism on the left, he said, might be the mayoral campaign of Zohran Mamdani, whose platform included a promise to freeze the rent.

“He’s a little bit slopulist,” Mr. Monahan said of Mr. Mamdani, adding, “This is the feel-good model of politics where the mechanics are less important than taking credit and celebrating.”

For some, it is likely to be one of the more rewarding ways to practice politics in modern-day America.

“I don’t want to live a life of quiet desperation,” Ms. Reichert said.

Mr. Shirley, in recent days, has been staying the course, too. While he has moved on from Minnesota, he’s still making videos about fraud aimed at immigrant-operated day care centers. But this time he’s in California and has a new collaborator by his side: Ms. Reichert.

Last month, she posted a photograph of herself and Mr. Shirley on X that has been viewed 1.4 million times. Using a flame emoji, she wrote: “California, here we come!”

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Alabama1 week ago

Alabama1 week agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Ohio1 week ago

Ohio1 week agoOhio town launching treasure hunt for $10K worth of gold, jewelry

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoIs Emily Brontë’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ Actually the Greatest Love Story of All Time?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe Long Goodbye: A California Couple Self-Deports to Mexico

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoVideo: Rare Giant Phantom Jelly Spotted in Deep Waters Near Argentina

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoVideo: Farewell, Pocket Books

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Investigators Say Doorbell Camera Was Disconnected Before Nancy Guthrie’s Kidnapping