Entertainment

Upheaval wrestles with tradition in Korean art of the 1960s and ’70s at the Hammer Museum

Seoul is the latest major city to establish itself as a significant international hub for new art. With that distinction comes the expected propagation of ambitious museum exhibitions seeking to articulate, illuminate and cogitate over its local history of modern art, which is little known.

“Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s” is the latest. It follows “The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art,” which a year ago covered 1897 to 1965 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“Only the Young,” organized last year by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, working with Korea’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, is at the UCLA Hammer Museum in Westwood through May 12. It’s the first show of its kind in North America. With 29 artists and nine artist groups, the exhibition is anchored by varieties of Conceptual art, which became the leading form internationally in the decades under review. The result is work that feels at once recognizable and unfamiliar, which sometimes makes for a bit of a tough haul, if also a nicely curious experience.

The history of the participating Korean museum suggests some of what you’ll find explored in the show. The institution, founded in 1969, smack in the middle of the exhibition timeline, has now branched out into four satellites — Gwacheon, Deoksugung, Cheongju and Seoul, most of them in and around the nation’s capital. Those sites represent shifting centers of power, influence and reigning cultural philosophy within the country, beginning with the isolationist Joseon dynasty that ruled for half a millennium, before the tumultuous modern era.

Of the 29 artists, all but two, Jung Kangja and Lee Hyangmi, are men. That’s one indication of the deep social conservatism of an era of rebuilding after the Korean War, which was led by strongman Park Chung Hee. His tenure — Park took power in a 1961 military coup and was assassinated while still in office in 1979 — brackets the show’s “experimental” era.

A timeline of Korean performance art leads to Song Burnsoo’s “Take Cover I-V,” five silkscreen images.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Jung’s participation in a satirical 1968 performance stands out. In a happening that parodied academic female nudes painted by men, her male colleagues, Chung Chanseung and Kang Kukjin, attached transparent balloons to her semi-naked body. The balloons then were popped, one by one, to fully expose the 26-year-old artist.

A hit with their avant-garde coterie, partly for its virtually unprecedented feminist insistence on a living, breathing woman’s centrality to the project, the event didn’t go down well everywhere, including in a scandalized Korean popular press. (Police were also on hand to observe.) Two years later, annoyed authorities shuttered a survey exhibition of Jung’s work.

Jung, Chung and Kang had all been students in the department of Western painting at Seoul’s Hongik University. That such a department existed shows where certain official Asian ambitions lay: The Western establishment was the standard for what “modern” meant. Many young Korean artists worked in groups, affiliated formally or loosely, which may suggest just how minimized experimentation was. (There’s strength in numbers.) Amid churning local political controversies around national identity, the students surely were looking to developments in Europe and the United States for artistic inspiration, with contemporary art magazines as a guide.

At the Hammer, “Transparent Balloons and Nude” is represented by a slightly blurry photograph, displayed with other still and video images of performance art in a helpful timeline that spreads across a wall. The performance indicates obvious debts to slightly earlier Western works.

Among them are Yves Klein’s 1960 performance in Paris, “Anthropometry of the Blue Period,” in which nude women were slathered in blue paint and then imprinted their bodies on canvas; and Yoko Ono’s 1964 “Cut Piece,” first performed in Tokyo and then London and New York (at Carnegie Hall, no less), where she sat alone on a stage while members of the audience were invited to come up and cut off pieces of her clothing. Neither of these cutting-edge Western precedents required police to be in attendance, which yields dramatic — and courageous — resonance for the Koreans’ performance.

Park Hyunki, “Untitled (TV Stone Tower),” 1982, mixed media.

(Hammer Museum)

L.A. is home to the largest Korean diaspora, but the country’s history, which may or may not be familiar to Hammer visitors, illuminates what artists were up to. It was not always to profound effect. For instance, Andy Warhol is an obvious marker for Song Burnsoo’s “Take Cover I-V,” five silkscreen images that repeat a gas-masked face, its sequence of solid colors representing coded government alarms related to threats from North Korea. The work’s Pop social commentary is pretty thin.

More intriguing is Park Hyunki’s “Untitled (TV Stone Tower),” which inserts a television monitor within a short stack of hefty stones, surrounded by additional scattered rocks. (Here the show fudges a bit, since the work is dated 1982.) In this Brancusi-inflected “endless column,” commercially produced and ephemeral mass imagery is juxtaposed with an actual, if abbreviated, mass drawn from nature, creating an oddly poignant sense of loss. The effect is only enhanced by learning from the show’s excellent catalog that Park’s composition refers to traditional Korean doltap, stone piles erected at temples to drive away evil spirits.

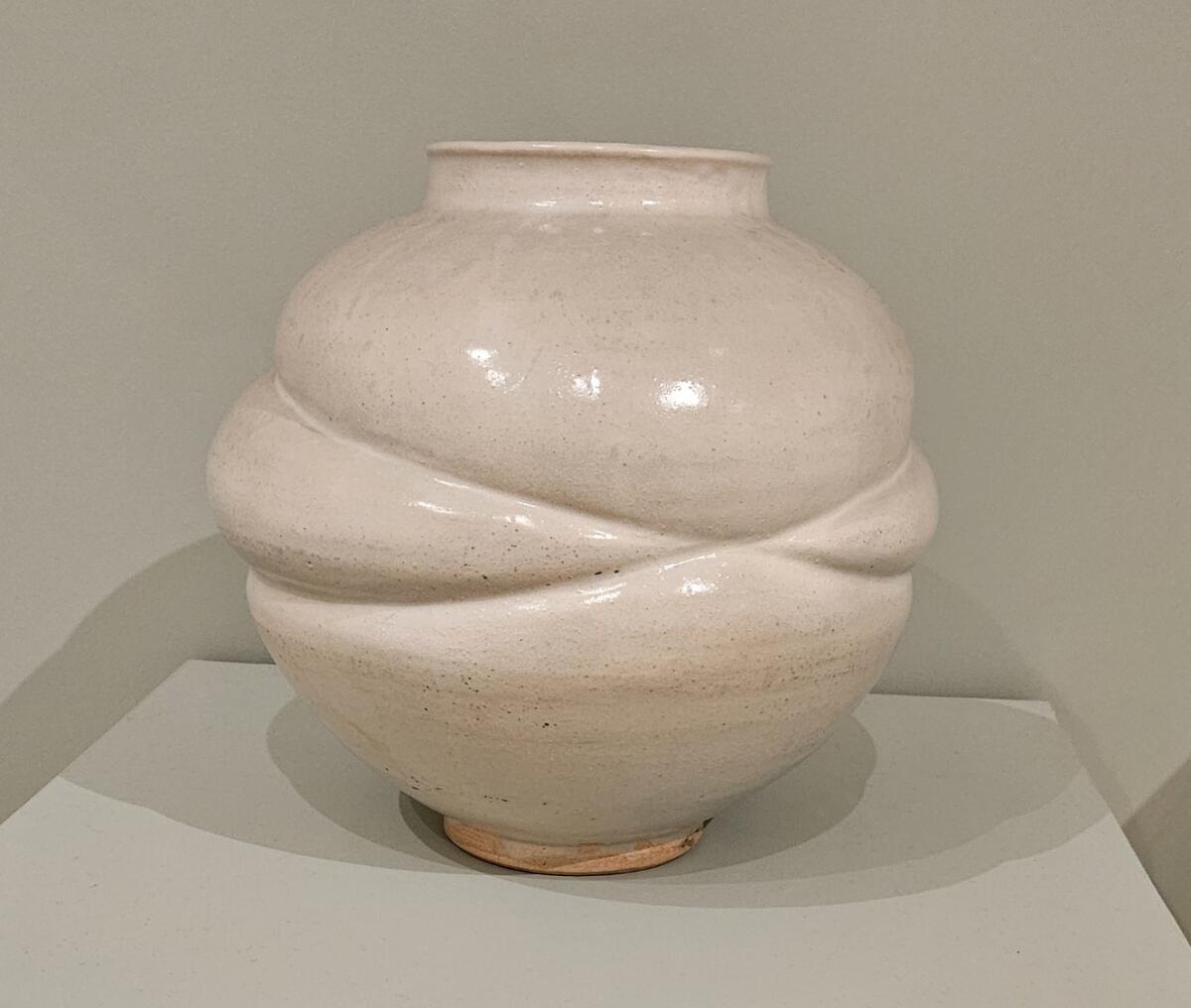

Two of the show’s simplest works are among its most hauntingly beautiful. Lee Seung-taek’s “Tied Ceramic” and Ha Chong-Hyun’s “Work 73-13” both date from the early 1970s, a time of serious national distress that included ramifications from participation in the Vietnam War.

“Tied Ceramic” leaves the tracks of a rope that, before firing in a kiln, were wound around a white porcelain moon jar, an exquisite traditional form highly revered during the premodern Joseon dynasty. The wrapping marks, cut into the clay like a memory made concrete, oscillate between signs of painful bondage and a warm embrace, a tension both social and artistic in 1970s Korean culture.

Lee Seung-taek, “Tied Ceramic,” 1975, porcelain.

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

“Work 73-13” is a large, earthy, monochrome abstraction, its mottled muddy color achieved by pushing brown oil paint through rough jute from behind. Almost 4 feet tall and nearly 8 feet wide, the plane is wrapped in a strict grid of barbed wire. The aesthetic effect is of nature, tradition, human effort and modernity imprisoned but unstoppable. It will all ooze out.

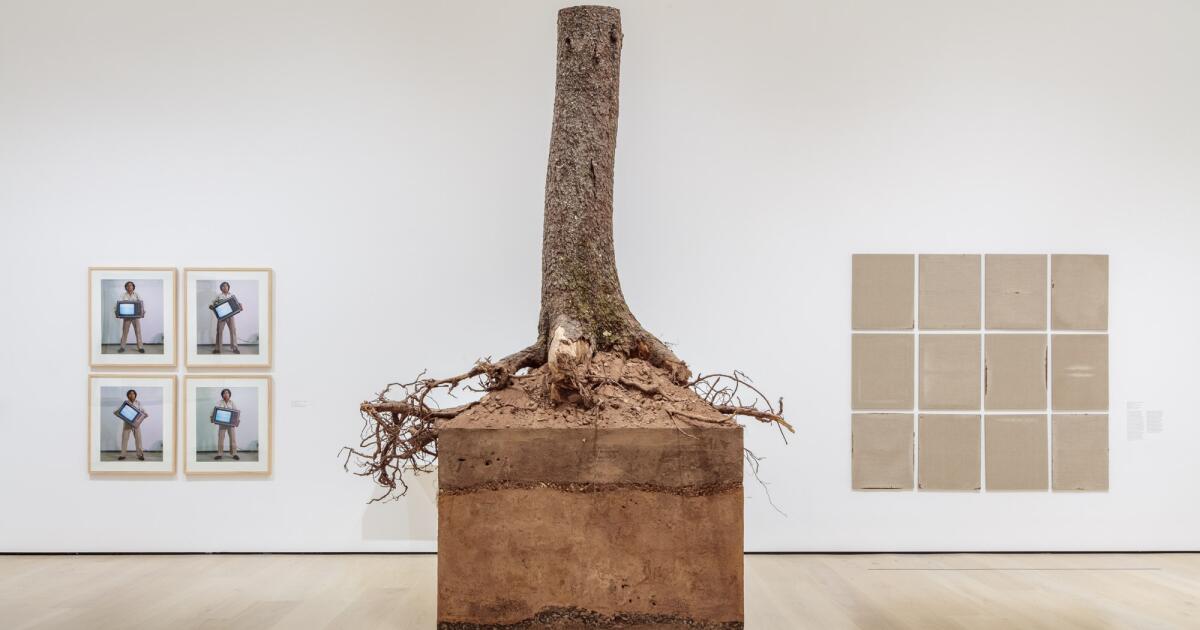

A kind of exclamation point marks the final room, where a tall, severed tree stump rises from a big, precisely carved cube made of soil, gravel and concrete. Lee Kun-Yong’s sculpture “Corporal Term,” which sits atop a wooden pallet, is remade whenever it is shown, its natural elements scavenged from local sources. (A Hammer label is careful to note that this particular tangled stump was found as is; no trees were harmed to make the art.) The title “Corporal Term” describes the bodily lifespan of the sculpture, the human effort to fabricate the form, the viewer’s experience of it — even, perhaps, the long arc of Korean history that has brought the object here. The work is a lovely meditation on mortality and endurance.

Kim Kulim, who worked in Los Angeles in the 1990s, emerges from “Only the Young” as an essential artist for the experimental activity that erupted in 1960s Korea. At the show’s entrance, his painting “Death of the Sun II” (1964) is a scarred, all-black panel, made from paint covered with a petroleum-doused vinyl sheet that was set on fire and then smothered. The battered panel — painting as performance art — takes a cue from Shōzō Shimamoto, Saburō Murakami and other Gutai aesthetics of 1950s Japan, which emerged from the apocalyptic ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Ha Chong-Hyun, “Work 73-13,” 1973, mixed media.

(Ariel Ione Williams)

“Death of the Sun II” metaphorically destroys both the revered Korean tradition of black ink painting and modern Western abstraction, whose epitome was said to be the structural void represented by the all-black paintings of 1950s American artists Robert Rauschenberg, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko and Frank Stella. As the show unfolds, Kim turns up in several disparate guises — making films, producing happenings, wiring a big electrified panel of dancing lights — leaving one to wonder what a full solo retrospective might reveal.

Conceptual art was both an extension and a critique of modernism. A common though mistaken assumption is that varieties of Conceptual art erupted in New York and eventually spread out to cover the art globe, as Abstract Expressionist, Pop, Minimal and street art are often erroneously claimed to have done. Rather than representing a cultural center and its periphery, however, the artistic shift in the 20th century’s second half had multiple points of origin all over the globe. Seoul and its environs formed one of them. “Only the Young” does an admirable job of presenting the Korean dialect of Conceptual art’s emergent international language.

‘Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s’

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Through May 12. 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesdays to Sundays, 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; closed Mondays

Admission: Free

Info: hammer.ucla.edu, (310) 443-7000

Movie Reviews

Reagan Is Almost Fun-Bad But It’s Mostly Just Bad-Bad

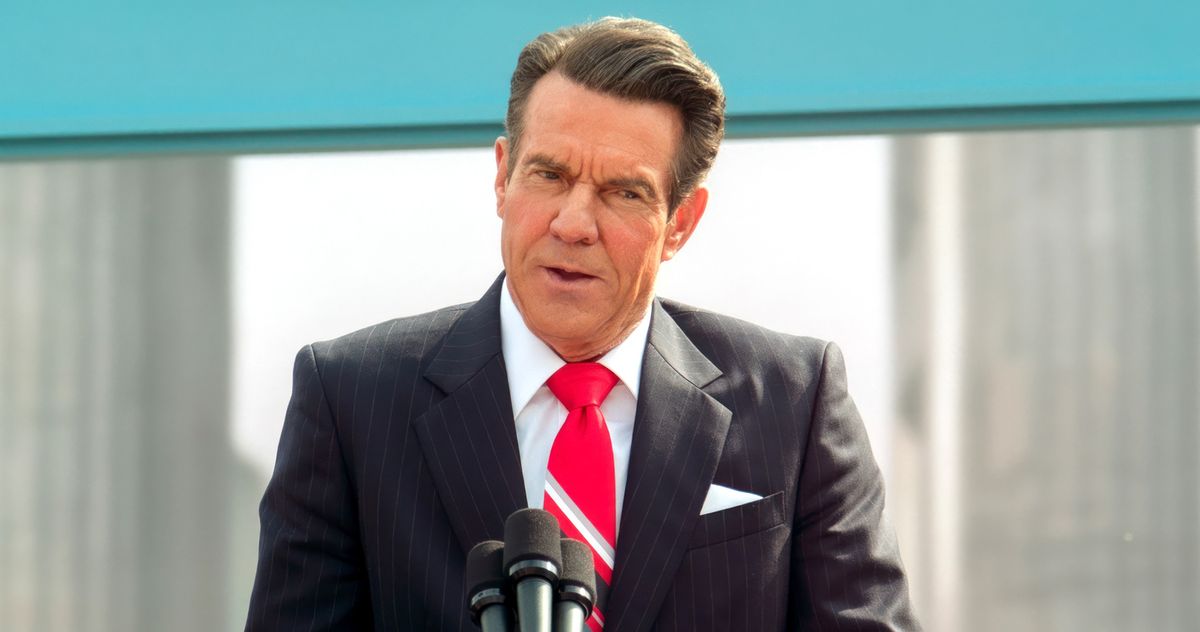

Dennis Quaid in Reagan.

Photo: Showbiz Direct/Everett Collection

Reagan is pure hagiography, but it’s not even one of those convincing hagiographies that pummel you into submission with compelling scenes that reinforce their subject’s greatness. Sean McNamara’s film has slick surfaces, but it’s so shallow and one-note that it actually does Ronald Reagan a disservice. The picture attempts to take in the full arc of the President’s life, following him from childhood right through to his 1994 announcement at the age of 83 that he’d been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. But you’d never guess that this man was at all complex, complicated, conflicted — in other words, human. He might as well be one of those animatronic robots at Disney World, mouthing lines from his famous speeches.

Dennis Quaid, a very good actor who can usually work hints of sadness into his manic machismo, is hamstrung here by the need to impersonate. He gets the voice down well (and he certainly says “Well” a lot) and he tries to do what he can with Reagan’s occasional political or career setbacks, but gone is that unpredictable glint in the actor’s eye. This Reagan doesn’t seem to have much of an interior life. Everything he thinks or feels, he says — which is maybe an admirable trait in a politician, but makes for boring art.

The film’s arc is wide and its focus is narrow. Reagan is mainly about its subject’s lifelong opposition to Communism, carrying him through his battles against labor organizers as president of the Screen Actors Guild and eventually to higher public office. The movie is narrated by a retired Soviet intelligence official (Jon Voight) in the present day, answering a younger counterpart’s questions about how the Russian empire was destroyed. He calls Reagan “the Crusader” and the moniker is meant to be both combative and respectful: He admires Reagan’s single-minded dedication to fighting the Soviets. They, after all, were single-minded in their dedication to fighting the U.S., and the agent has a ton of folders and films proving that the KGB had been watching Reagan for a long, long time.

By the way, you did read that correctly. Jon Voight plays a KGB officer in this picture, complete with a super-thick Russian accent. There’s a lot of dress-up going on — it’s like Basquiat for Republicans, even though the cast is certainly not all Republicans — and there’s some campy fun to be had here. Much has been made of Creed’s Scott Stapp doing a very flamboyant Frank Sinatra, though I regret to announce that he’s only onscreen for a few seconds. Robert Davi gets more screentime as Leonid Brezhnev, as does Kevin Dillon as Jack Warner. Xander Berkeley puts in fine work as George Schultz, and a game Mena Suvari shows up as an intriguingly pissy Jane Wyman, Reagan’s first wife. As Margaret Thatcher, Lesley-Anne Down gets to utter an orgasmic “Well done, cowboy!” when she sees Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall” speech on TV. And my ’80s-kid brain is still processing C. Thomas Howell being cast as Caspar Weinberger.

To be fair, a lot of historians give Reagan credit for helping bring about both the Gorbachev revolution and the eventual downfall of the U.S.S.R. and its satellites, so the film’s focus is not in and of itself a misguided one. There are stories to be told within that scope — interesting ones, controversial ones, the kind that could get audiences talking and arguing, and even ones that could help breathe life into the moribund state of conservative filmmaking. But without any lifelike characters, it’s hard to find oneself caring, and thus, Reagan’s dedication to such narrow themes proves limiting. We get little mention of his family life (aside from his non-stop devotion to Nancy, played by Penelope Ann Miller, and vice versa). Other issues of the day are breezed through with a couple of quick montages. All of this could have given some texture to the story and lent dimensionality to such an enormously consequential figure. But then again, if the only character flaw you could find in Ronald Reagan was that he was too honest, then maybe you weren’t very serious about depicting him as a human being to begin with.

See All

Entertainment

How Toto held the line

Steve Lukather has lived in his house overlooking Studio City since 1979 — longer than you’d expect, perhaps, given that he bought the place before his band Toto exploded with its fourth album, 1982’s quadruple-platinum “Toto IV,” which won Grammy Awards for album and record of the year and spawned a chart-topping single in the yearning, sumptuous, still-inescapable “Africa.”

“I don’t live a big, huge, stupid life,” Lukather says, brushing away any surprise that he didn’t upgrade as soon as he had the chance. “I like my little crib in the hills.” With a laugh, he adds, “I got it before both divorces, and I got to keep it.”

Lukather is hanging at home on a recent afternoon, barefoot as he sips a nonalcoholic Corona, with his bandmates David Paich and Joseph Williams. The walls are lined with plaques commemorating the millions of records sold by Toto and by some of the countless acts with whom Lukather has played in the studio; books about the Beatles and about rock’s greatest album covers are piled neatly on the fireplace.

In the middle of the modest living room sits a gleaming Steinway grand piano — the very one, Lukather points out, on which he wrote two of Toto’s biggest ballads, “I Won’t Hold You Back” and “I’ll Be Over You,” as well as “Turn Your Love Around,” which George Benson took to No. 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart in 1982.

Yet Lukather isn’t living in the past. On Sunday night, nearly four decades after the band last grazed the Hot 100, Toto will headline the Hollywood Bowl for the first time. The hometown show is part of a broader resurgence for a group of guys in their 60s and 70s who currently boast 30 million monthly listeners on Spotify — more than the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen or Eric Clapton — and who’ve survived long enough to see their once-derided yacht-rock vibe come back into vogue.

What’s more, Toto is on the road with two founding members in guitarist Lukather and keyboardist Paich at a moment when some classic rock bands are lucky to claim a single OG. (Take a bow, Foreigner.)

How to explain Toto’s endurance? For sure, the band has been lifted by a rising tide for all legacy acts: a kind of catch-’em-while-you-can mind-set that’s helped draw huge audiences to the likes of Billy Joel, the Eagles, Stevie Nicks and Dead & Company. In 2022, Toto opened for Journey on a U.S. arena tour; this summer, Journey is playing stadiums with Def Leppard.

There’s also the songs, of course — “a couple of which have just struck a nerve with people,” says Williams, who joined Toto as lead singer in 1986. He means “Hold the Line,” the band’s hard-riffing breakthrough, and the swank “Rosanna,” which beat Willie Nelson’s “Always on My Mind” and the theme from “Chariots of Fire” for record of the year at the Grammys. But what he really means is “Africa,” that fever dream about a rain-blessing excursion that’s been memed to high heaven, been used on “South Park” and “Stranger Things” and been covered by Weezer as a joke that no one can quite figure out. On Spotify, the song has racked up nearly 2 billion streams.

According to Williams, these hits have “lived past the knowledge of the band itself,” as he puts it.

“I was on an elevator once in a hotel when we were on the road, and there were two couples in there,” he says. “One woman was saying to the other woman, ‘What are you guys doing tonight?’ and she says, ‘We’re going to see that band Africa.’”

“Imagine their disappointment when we walked out,” Lukather says.

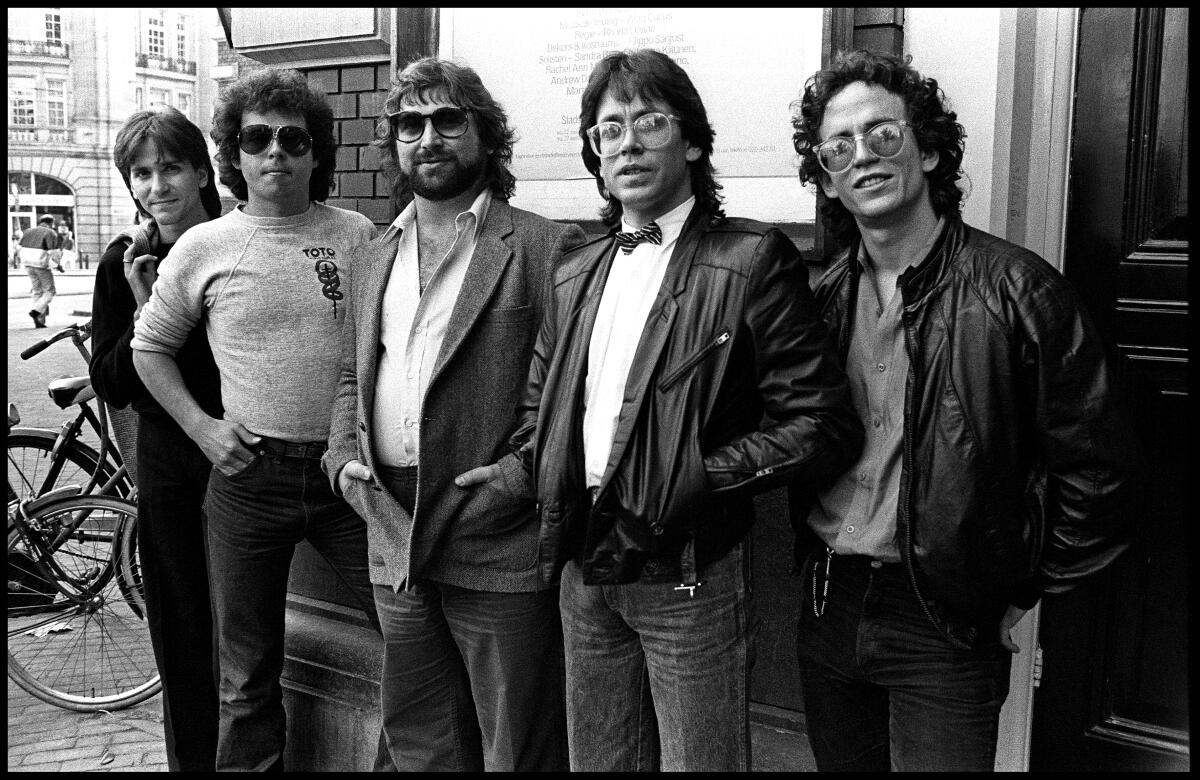

As individuals, though, the members of Toto — among the other founders were the brothers Jeff and Steve Porcaro on drums and keys, respectively — have inspired a certain fascination, at least among music nerds, with the way they balanced the band with busy side careers as studio players who shaped the slick but soulful sound of ’80s pop.

Michael McDonald’s “I Keep Forgettin’,” Don Henley’s “The Boys of Summer,” Michael Jackson’s uber-blockbuster “Thriller” LP — all featured Lukather, Paich and/or the Porcaros. Also: Olivia Newton-John’s “Physical,” a framed platinum copy of which hangs next to one of Jackson’s “Beat It” by Lukather’s dining room table.

“These guys in their sleep could do it pretty much on the first take,” says David Foster, the veteran record producer who started out as a fellow session musician — you can hear both him and Paich behind Benson on “Turn Your Love Around” — before becoming the one hiring Toto’s members to play on hit records like Chicago’s “Hard to Say I’m Sorry.”

“It was just an amazing array of musicians,” he adds. “David Paich has the best feel of any piano player I’ve ever met.”

Toto in Amsterdam in 1982: Mike Porcaro, from left, Steve Lukather, David Paich, Jeff Porcaro and Steve Porcaro.

(Rob Verhorst / Redferns / Getty Images)

Toto’s high-gloss only-in-L.A. aesthetic didn’t age well into the ’90s and early 2000s, when rock went grungy then garage-y; even in Toto’s heyday, critics dismissed the band as hot-dogging technicians. (Rolling Stone’s oft-quoted dismissal: “All chops and no brains.”)

Yet a new generation of acts — Haim, Bon Iver, the War on Drugs, Mk.gee — has lovingly embraced the intricate sense of craft that Toto built into its records. And though the members’ session work wasn’t highly visible in the early, no-liner-notes era of digital music, their contributions are now eagerly tracked on websites like Discogs and in music docs like this year’s “The Greatest Night in Pop,” about the recording of “We Are the World” — one more defining mid-’80s smash that featured Paich and Steve Porcaro on keyboards.

“Everybody knows Toto, but you only really know Toto when you know all the other things they worked on and how sick they were in any circumstance,” says Ethan Gruska, a young L.A. musician and producer who’s convened a not-dissimilar crew of musicians to make not-dissimilarly tasty records with Phoebe Bridgers and Ryan Beatty. “Obviously, I’m biased” — Gruska is Williams’ nephew — “but my friends who are players have always thought that what they established was cool.”

Which isn’t to say that Lukather, Toto’s intellectual thought leader, is without his share of older-rock-star grievances. Among them:

- the term “yacht rock” (“We deserve a yacht, don’t you think?” he asks)

- the fact that Toto hasn’t been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (“It’s not based on stats — it’s based on the taste of 80-year-old men”)

- clueless record execs (“Walter Yetnikoff knew nothing about music,” he says of the late CBS Records boss)

- Weezer frontman Rivers Cuomo’s unwillingness to meet Toto after its hit “Africa” cover (“The guy just iced me”)

Still, asked whether he identifies a bitterness within himself, Lukather scoffs.

“F— no,” he says. “How could I be bitter with a career that’s almost 50 years old?”

Toto formed out of friendships struck up at Grant High School in the Valley. Nobody called anybody “nepo babies” back then, but the members of Toto were all connected: Paich’s father was Marty Paich, the arranger and conductor known for his work with Ray Charles and Barbra Streisand, among many others; the Porcaro brothers were the sons of the jazz drummer Joe Porcaro; Lukather’s dad worked in TV production on shows like “I Dream of Jeannie.” (No wonder that when they needed a new singer after frontman Bobby Kimball left the band, they clicked with Williams, son of the celebrated film composer John Williams.)

The players had already proved themselves as session guys — Boz Scaggs’ “Silk Degrees” was a crucial showcase — when they cut Toto’s self-titled debut in 1978 and scored a top 10 hit with “Hold the Line.” For the next year’s “Hydra,” “we started to go all Dungeons & Dragons on everybody,” Lukather says; the result whiffed, as did 1981’s “Turn Back.” But with “Toto IV” the band found just the right blend of groove, melody and texture, a sweet spot it stayed in for a few glorious years.

Did Toto’s famous perfectionism in the studio ever suck the joy out of making music?

“Sometimes,” Williams says, shaking his head beneath a black cowboy hat. “I spent a few times behind the glass where the joy had left my body.”

Lukather, for one, still loves getting deep into the weeds of recording; last year he released an album of new songs under his own name even though he knew he wouldn’t make any money from it. The paying work — not to mention the validation he’s grown accustomed to receiving from an audience — is onstage, which is one reason he went into something of a tailspin during the pandemic when live music ground to a halt.

The guitarist doesn’t want to go into detail about it today. But as he told the music-industry analyst Bob Lefsetz last year in an episode of Lefsetz’s podcast, Lukather struggled with depression and a subsequent bout with ketamine abuse. So when Toto finally got back on the road with Journey two years ago, he says, “it made me appreciate life like I’ve never appreciated it before.”

The tour reenergized Toto’s live business as well. “People saw us and went, ‘Wow, these guys are actually good,’” Lukather says.

Surely, the members of Toto saw the recent news that Journey’s Jonathan Cain had filed a lawsuit accusing the band’s Neal Schon of misusing the band’s corporate credit card — while the two are in the midst of playing concerts together? Williams laughs. “They need the money from the shows to keep suing each other,” he says.

“We’ve gotten close to that,” Lukather adds. “It’s not pleasant.” (Fun classic-rock fact: Lukather’s son is married to Cain’s daughter.)

Lukather doesn’t name names in regards to this almost-litigation. But asked why his solo record wasn’t a Toto album — Paich and Williams are both all over it — he says, “Don’t want to deal with fighting people over semantics.” Susan Porcaro Goings, widow of the late Jeff Porcaro (who died in 1992), has sued the band over her share of Toto’s royalties; Steve Porcaro quit Toto in 2019. Why did Steve Porcaro leave?

“The last tour he was on, he was so miserable every day,” Lukather says. Reached on the phone, Porcaro says, “I don’t know what he’s talking about. I was very, very happy on the road. I just needed a break.”

Last month, Porcaro announced that he’d sold the rights to his music — including the Toto songs he had a hand in as well as the indelible Michael Jackson hit “Human Nature,” which he co-wrote with lyricist John Bettis — in a deal with the Jackson estate and the music company Primary Wave. (The New York Times reported that the deal, the latest in a long series of catalog transactions involving veteran pop and rock artists, was “estimated in the low eight figures.”)

“OK, so 10, 11, 12 million?” Lukather asks. “I don’t know, I haven’t talked to him about it. But most of the people I know that have sold have regretted it.” He’s been approached, he adds, and said no every time. Lukather’s view is that it’s smarter to resist a one-time payout — “Living in California, they take 50%, boom, right off the bat” — and instead keep the royalty checks coming “a couple times a year,” he says.

“Also, you have no say [after selling your rights] if somebody wants to make a toilet-paper commercial out of one of your songs,” he adds. “That’s my life and my creativity balled into this thing called music. It’s personal.”

Steve Lukather and Joseph Williams of Toto perform in Madrid in July.

(Mariano Regidor / Redferns / Getty Images)

For these reasons and others, Lukather serves as Toto’s manager, which he reckons keeps him busy on the phone and the computer for at least four hours every morning before whatever musical labor the day holds. Like the catalog buyers, would-be managers have tried to woo Toto.

“There’s been a lot of fabulous people — put ‘fabulous’ in quotes — and they all have 20 acts yet still find time to play golf every day,” he says. They’ll promise they can work untold wonders for the band, he adds. “It’s like dating — you’ll say anything you can think of to get those pants off.”

Which, considering the strong shape Toto is in, just makes Lukather laugh. “If we were sucking the last bit of air out of the tire, it’d be a different conversation,” he says. “But we’re headlining a stadium show in Amsterdam in February. We’re doing 80,000 people at a festival in Mexico City with Paul McCartney and Green Day, and our name’s right there. It’s astounding to me, man.

“This is getting bigger, not smaller. I’ll take the ride for a while.”

Movie Reviews

‘Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight’ Review: An Extraordinary Adaptation Takes a Child’s-Eye View of an African Civil War

Alexandra Fuller‘s bestselling 2001 memoir of growing up in Africa is so cinematic, full of personal drama and political upheaval against a vivid landscape, that it’s a wonder it hasn’t been turned into a film before. But it was worth waiting for Embeth Davidtz’s eloquent adaptation, which depicts a child’s-eye view of the civil war that created the country of Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia — a change the girl’s white colonial parents fiercely resisted.

Davidtz, known as an actress (Schindler’s List, among many others), directs and wrote the screenplay for Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and stars as Fuller’s sad, alcoholic mother. Or, actually, co-stars, because the entire movie rests on the tiny shoulders and remarkably lifelike performance of Lexi Venter — just 7 when the picture, her first, was shot. It is a bold risk to put so much weight on a child’s work, but like so many of Davidtz’s choices here, it also turns out to be shrewd.

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight

The Bottom Line Near perfection.

Venue: Telluride Film Festival

Cast: Lexi Venter, Embeth Davidtz, Zikhona Bali, Fumani N Shilubana, Rob Van Vuuren, Anina Hope Reed

Director-screenwriter: Embeth Davidtz

1 hour 38 minutes

Another those smart calls is to focus intensely on one period of Fuller’s childhood. Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is set in 1980, just before and during the election that would bring the country’s Black majority to power. Bobo, as Fuller was called, is a raggedy kid with a perpetually dirty face and uncombed hair, who’s seen at times riding a motorbike or sneaking cigarettes. She runs around the family farm, whose run-down look and dusty ground tell of a hardscrabble existence. The film was shot in South Africa, and Willie Nel’s cinematography, with glaring bright light, suggests the scorching feel of the sun.

Much of the story is told in Bobo’s voiceover, in Venter’s completely natural delivery, and in another daring and effective choice, all of it is told from her point of view. Davidtz’s screenplay deftly lets us hear and see the racism that surrounds the child, and the ideas that she has innocently taken in from her parents. And we recognize the emotional cost of the war, even when Bobo doesn’t. She often mentions terrorists, saying she is afraid to go into the bathroom alone at night in case there’s one waiting for her “with a knife or a gun or a spear.” She keeps an eye out for them while riding into town in the family car with an armed convoy. “Africans turned into terrorists and that’s how the war started,” she explains, parroting what she has heard.

At one point, the convoy glides past an affluent white neighborhood. That glimpse helps Davidtz situate the Fullers, putting their assumptions of privilege into context. Bobo has absorbed those notions without quite losing her innocence. Referring to the family’s servants, her voiceover says that Sarah (Zikhona Bali) and Jacob (Fumani N. Shilubana) live on the farm, and that “Africans don’t have last names.” Bobo adores Sarah and the stories she tells from her own culture, but Bobo also feels that she can boss Sarah around.

Venter is astonishing throughout. In close-up, she looks wide-eyed and aghast when visiting her grandfather, who has apparently had a stroke. At another point, she says of her mother, “Mum says she’d trade all of us for a horse and her dogs.” When she says, after the briefest pause, “But I know that’s not true,” her tone is not one of defiant disbelief or childlike belief, as might have been expected. It’s more nuanced, with a hint of sadness that suggests a realization just beyond her young grasp. Davidtz surely had a lot to do with that, and her editor, Nicholas Contaras, has cut all Bobo’s scenes into a sharply perfect length. Nonetheless, Venter’s work here brings to mind Anna Paquin, who won an Oscar as a child for her thoroughly believable role as a girl also who sees more than she knows in The Piano.

The largely South African cast displays the same naturalism as Venter, creating a consistent tone. Rob Van Vuuren plays Bobo’s father, who is at times away fighting, and Anina Hope Reed is her older sister. Bali and Shilubana are especially impressive as Sarah and Jacob, their portrayals suggesting a resistance to white rule that the characters can’t always speak out loud.

Davidtz has a showier role as Nicola Fuller. (The movie doesn’t explain its title, which hails from the early 20th century writer A.P Herbert’s line, “Don’t let’s go the dogs tonight, for mother will be there.”) Once, Nicola shoots a snake in the kitchen and calmly wanders off, ordering Jacob to bring her tea. More often, Bobo watches her mother drift around the house or sit on the porch in an alcoholic fog. But when her voiceover tells us about the little sister who drowned, we fathom the grief behind Nicola’s depression. And wrong-headed though she is, we understand her fury and distress when the election results make her feel that she is about to lose the country she thinks of as home. Davidtz gives herself a scene at a neighborhood dance that goes on a bit too long, but it’s the rare sequence that does.

There is more of Fuller’s memoir that might be a source for other adaptations. It is hard to imagine any would be more beautifully realized than this.

-

Connecticut1 week ago

Connecticut1 week agoOxford church provides sanctuary during Sunday's damaging storm

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoBreakthrough robo-glove gives you superhuman grip

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoClinton lauds Biden as modern-day George Washington and president who 'healed our sick' in DNC speech

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago2024 showdown: What happens next in the Kamala Harris-Donald Trump face-off

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWho Are Kamala Harris’s 1.5 Million New Donors?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taunted over speculated RFK Jr endorsement: 'Weird as hell'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVivek Ramaswamy sounds off on potential RFK Jr. role in a Trump administration

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoPortugal coast hit by 5.3 magnitude earthquake