Entertainment

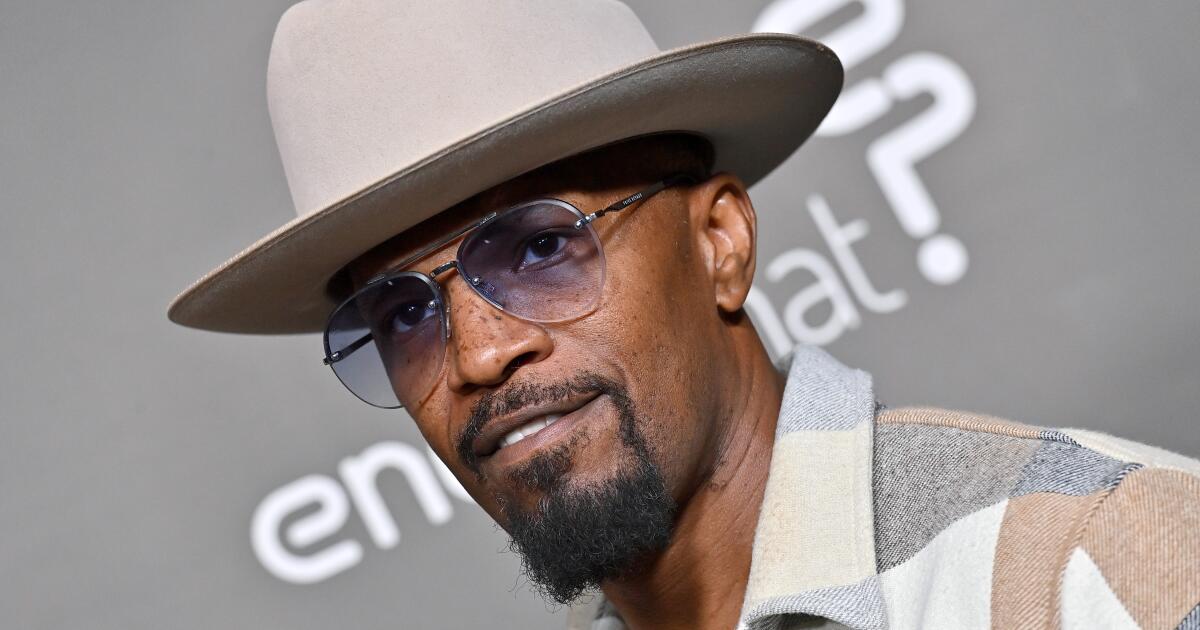

Jamie Foxx reveals he had a stroke in Netflix stand-up special: 'I don't remember 20 days'

Jamie Foxx is finally telling the whole story about his hospitalization last year in the language he knows best: comedy.

In his new comedy special released Tuesday, the Oscar winner revealed that he suffered a stroke last April. At that time, Foxx’s family had released a since-deleted statement that he was receiving care for an undisclosed “medical complication.”

While Foxx continued to share updates on his recovery, he declined in March to tell the full story until he could do so “in a funny way,” Variety reported.

He made good on that promise with arrival of his Netflix stand-up special “What Had Happened Was.”

During the 68-minute show, Foxx recounts his months-long health journey — beginning with the April evening when a “bad headache” turned much graver.

“I asked my boy for a aspirin,” he recalled, “and I realized quickly that when you in a medical emergency, your boys don’t know what the f— to do.

“Before I could get the aspirin,” he continued, pausing to snap his fingers, “I went out. I don’t remember 20 days.”

With the help of friends and family, Foxx said he pieced together an account of what happened immediately after. The first doctor to see him administered a cortisone shot and sent him off with “half-star service,” he quipped.

But his younger sister Deidra Dixon, who he called “4 foot of nothing but pure love,” wasn’t satisfied. So she drove until she came upon Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital. She had never heard of the facility before, Foxx said, “but she had a hunch that some angels is in there.”

That doctor said Foxx had a brain bleed that had led to a stroke, the comedian said, and his sister continually prayed during his entire operation.

“They put me back together again,” Foxx said. “Atlanta saved my life.”

When he finally woke up one morning in May 2023, “The Jamie Foxx Show” star said he was startled to find himself in a wheelchair and stubbornly insisted on attempting to walk. Dramatically reenacting the scene in the special, Foxx’s legs tremble, his eyes wide. In the end, he said he admitted defeat.

Throughout the special, the “Just Mercy” actor also joked about his daughter Corinne’s fears that he would be “memed” for his condition, adding that being bathed by his nurse was more scarring than the stroke itself.

“You have no idea how good this feels,” Foxx told the Atlanta crowd as he opened his set. “If I dance all night, don’t mind me. I’m happy to be alive.”

Corinne Foxx first announced in April 2023 that Foxx was being treated for a medical emergency. In response to her since-deleted announcement, speculation arose about the details of the emergency. Corinne later slammed such rumors, lamenting “how the media runs wild” and adding that her dad had “been out of the hospital for weeks, recuperating.”

The revelation about Foxx’s stroke did not come until “What Had Happened Was.” Before Tuesday, the actor had spoken publicly about the medical emergency without details. He has also regularly updated fans on social media about his health and well-being.

Meanwhile, “Back in Action,” Foxx’s action movie with Cameron Diaz, releases in theaters Jan. 17.

Filming for the movie was delayed upon Foxx’s April 2023 hospitalization. In January, Page Six published photos of the co-stars seemingly on set, though it is unclear if Foxx still had scenes to shoot.

Times staffers Nardine Saad and Alexandra Del Rosario contributed to this report.

Movie Reviews

Jeremy Schuetze’s ‘ANACORETA’ (2022) – Movie Review – PopHorror

PopHorror had the chance to check out Anacoreta (2022) ahead of its streaming release! Does this meta-horror flick provide interesting story telling or is it a confusing mess.

Let’s have a look…

Synopsis

A group of friends heads to a secluded woodland cabin for a weekend getaway, planning to film an experimental horror movie. As the shoot progresses, the project begins to fall apart—until a real and terrifying presence emerges from the darkness.

Anacoreta is directed by Jeremy Schuetze. It was written by Jeremy Schuetze and Matt Visser. The film stars Antonia Thomas (Bagman 2024), Jesse Stanley (Raf 2019), Jeremy Schuetze (Jennifer’s Body 2009), and Matt Visser (A Lot Like Christmas 2021)

My Thoughts

Antonia Thomas delivered an outstanding performance as the female lead in Anacoreta. It was remarkable to watch her convey such a wide range of emotions with authenticity and depth. I was continually impressed by her ability to switch seamlessly between different dialects. I absolutely loved her delivery of the dialogue of telling The Scorpion and the Frog fable.

Anacoreta employs a distinctive, meta-horror style of storytelling. The narrative follows a group of friends creating a “scripted reality” horror film, and as the plot unfolds, the boundary between their staged production and their actual lives becomes increasingly blurred. This was interesting, but at the same time frustrating as a viewer.

Check out Anacoreta on Prime Video and let us know your thoughts!

Entertainment

Todd Meadows, ‘Deadliest Catch’ deckhand, dies at 25

Todd Meadows, a crewmember on one of the fishing vessels featured on the long-running reality series “Deadliest Catch,” has died. He was 25.

Rick Shelford, the captain of the Aleutian Lady, announced in a Monday post on Facebook and Instagram that Meadows died Feb. 25. He called it “the most tragic day in the history of the Aleutian Lady on the Bering Sea.”

“We lost our brother,” Shelford wrote in his lengthy tribute. “Todd was the newest member of our crew, he quickly became family. His love for fishing and his strong work ethic earned everyone’s respect right away. His smile was contagious, and the sound of his laughter coming up the wheelhouse stairs or over the deck hailer is something we will carry with us always.

“He worked hard, loved deeply, and brought joy to those around him,” he added. “Todd will forever be part of this boat, this crew, and this brotherhood. Though we lost him far too soon, his legacy will live on through his children and in every memory we carry of him.”

A fundraiser set up in Meadows’ name described the deckhand from Montesano, Wash., as a father to “three amazing little boys” who died “while doing what he loved — crabbing out on Alaskan waters.”

According to the Associated Press, Meadows died after he was reported to have fallen overboard around 170 miles north of Dutch Harbor, Alaska.

“He was recovered unresponsive by the crew approximately ten minutes later,” Chief Petty Officer Travis Magee, a spokesperson with the Coast Guard’s Arctic District, told the AP. The Coast Guard is investigating the incident.

Meadows was a first-year cast member of “Deadliest Catch,” the Discovery Channel reality series that follows crab fishermen navigating the perilous winds and waves of the Bering Sea during the Alaskan king crab and snow crab fishing seasons. The show debuted in 2005. No episodes from Meadows’ season has aired.

Deadline reported that the show was in production on its 22nd season when the incident occurred, with the Shelford-led Aleutian Lady being the last of the vessels still out at sea at the time. Production has subsequently concluded, per the outlet.

“We are deeply saddened by the tragic passing of Todd Meadows,” a Discovery Channel spokesperson said in a statement that has been widely circulated. “This is a devastating loss, and our hearts are with his loved ones, his crewmates, and the entire fishing community during this incredibly difficult time.”

Meadows is the latest among “Deadliest Catch” cast members who have died. Previous deaths include Phil Harris, a captain of one of the ships featured on the show, who died after suffering a stroke while filming the show’s sixth season in 2010. Todd Kochutin, a crew member of the Patricia Lee, died in 2021 from injuries he sustained while aboard the fishing vessel, according to an obituary. Other cast members have died from substance abuse or natural causes.

Movie Reviews

‘Hoppers’ review: Pixar’s best original movie in years

“So it’s like Avatar?” one character quips in Disney and Pixar’s “Hoppers,” bluntly translating the film’s high-concept premise for the sugar-fueled kids in the audience. And yes, the comparison is apt. The story follows a nature-obsessed teenage girl who manages to quite literally “hop” her consciousness into the body of a robotic beaver in order to spark an animal rebellion against a greedy mayor determined to bulldoze their forest for a freeway.

It’s a clever hook. The kind of big, elastic idea Pixar used to make look effortless. “Hoppers” does not reach the rarified air of “Up,” “Wall-E,” or “Inside Out,” but after a stretch of uneven originals like “Turning Red” and “Luca,” and outright misfires such as “Elemental” and “Elio,” this feels like a genuine course correction. The environmental messaging is clear without being preachy, the animals are irresistibly anthropomorphized, and the studio’s once-signature emotional sincerity is back in sturdy form.

Pixar can afford to gamble on originals when it has a guaranteed cash cow like this summer’s “Toy Story 5” waiting in the wings, but “Hoppers” earns its place in the catalogue. Director Daniel Chong crafts a warm, heartfelt film that occasionally strains under the weight of its own ambition, yet remains grounded by character and theme. Its meditation on conservation and animal displacement feels timely in a way that never tips into after-school-special territory.

We meet Mabel, voiced with bright conviction by Piper Curda, as a child liberating her classroom pets and returning them to the wild. Her moral compass is shaped by her grandmother, voiced by Karen Huie, who imparts wisdom about nature’s sanctity. True to both Pixar tradition and the broader Disney playbook, this beacon of guidance does not survive past the opening act. Loss, after all, is Pixar’s favorite inciting incident.

Years later, Mabel is still fighting the good fight, squaring off against the smarmy Mayor Jerry, voiced with slick menace by Jon Hamm. He plans to flatten the glade where Mabel and her grandmother once found solace. Mabel’s resistance feels noble but futile. The animals have already mysteriously vanished, the machinery is coming, and her last-ditch plan involves luring a beaver back to the abandoned forest in hopes of jumpstarting the ecosystem.

That’s when the film gleefully pivots into mad-scientist territory. At Beaverton University, Mabel discovers her professor, voiced by Kathy Najimy, has developed a device that can project human consciousness into synthetic animals. The process, dubbed “hopping,” allows Mabel to inhabit a robotic beaver and infiltrate the forest from within. It’s an inspired escalation that keeps the film buoyant even when the plotting grows predictable.

Her new posse includes King George, a lovably beaver voiced by Bobby Moynihan with distinct Bing Bong energy; a sharp-tongued bear voiced by Melissa Villaseñor; a regal bird king voiced by the late Isiah Whitlock Jr.; and a fish queen voiced by Ego Nwodim. As is often the case with Pixar, even in its lesser efforts, the world-building is meticulous. The animal hierarchy, complete with titles like “paw of the king,” is layered with jokes that play for kids while slyly winking at adults.

The plot ultimately follows a familiar template. Scrappy underdog rallies community. Corporate villain twirls metaphorical mustache. Emotional third-act sacrifice looms. At times, you can feel the machinery working a little too cleanly. Pixar, and Disney at large, has grown increasingly reliant on sequels and established IP, and “Hoppers” does not radically reinvent the wheel. In an animated landscape where films like “K-Pop: Demon Hunters,” “Across the Spider-Verse,” and “Goat” are pushing stylistic and narrative boundaries, being safe and sturdy may not always be enough.

And yet, there is something refreshing about a Pixar original that remembers how to tug at the heart without squeezing it dry. “Hoppers” is playful, peppered with cheeky needle drops, and builds to a sweet emotional catharsis that may or may not have left this critic a little misty-eyed. It feels earnest and engaged.

“Hoppers” may not be top-tier Pixar. But it is a welcome return to form, a reminder that the studio still knows how to marry big ideas with a bigger heart.

HOPPERS opens in theaters Friday, March 6th.

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts7 days ago

Massachusetts7 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO7 days ago

Denver, CO7 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Florida3 days ago

Florida3 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Maryland3 days ago

Maryland3 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Thrilling Books That Became Popular Movies