Entertainment

Happy 95th birthday, Frank Gehry. Let's give you the Disney Hall you really wanted

Over the last two decades, Walt Disney Concert Hall has blazed cultural trails like no place else. We can rightfully talk about the L.A. Philharmonic before and after Frank Gehry built it a hypnotizing new home. We can divide downtown L.A. into pre- and post-Disney. We can go so far as to distinguish orchestral life, not only in L.A. but everywhere, in the same way.

Gehry turns 95 on Wednesday, and the L.A. Phil season, which began with a gala led by Gustavo Dudamel celebrating the architect, has, in ongoing tributes to the hall and in just doing its thing for these nearly five months, readily revealed, week after week, all that Disney is. And, alas, all that Disney inexcusably isn’t. At least not yet. But the best of Disney first.

Building Disney was a long, laborious, contentious, financially dicey process, one for which we’ve never had a full or convincing account. I’ve never gotten straight answers about who did what to whom and when.

In 1987, Ernest Fleischmann, at the time the transformative head of the L.A. Phil, enticed Lillian Disney to give $50 million for a concert hall to be built in honor of her late husband, Walt, as an addition to the Music Center. Fleischmann, who had once hailed the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, built for the L.A. Phil in 1964 as an acoustic wonder, eventually pronounced it unworthy. It still is, but that’s another story.

Presumably, Fleischmann assured Lillian Disney that this generous sum would be sufficient for the new hall, knowing full well that much more would be needed (ultimately, more like $274 million). Although Fleischmann and Gehry were close friends, Gehry was viewed as far too radical for the conservative classical music establishment, which feared chain-link fences and whatnot. One Music Center board member proposed that the original blueprints for the Chandler be dug up and that they just build “the same damn thing” across the street.

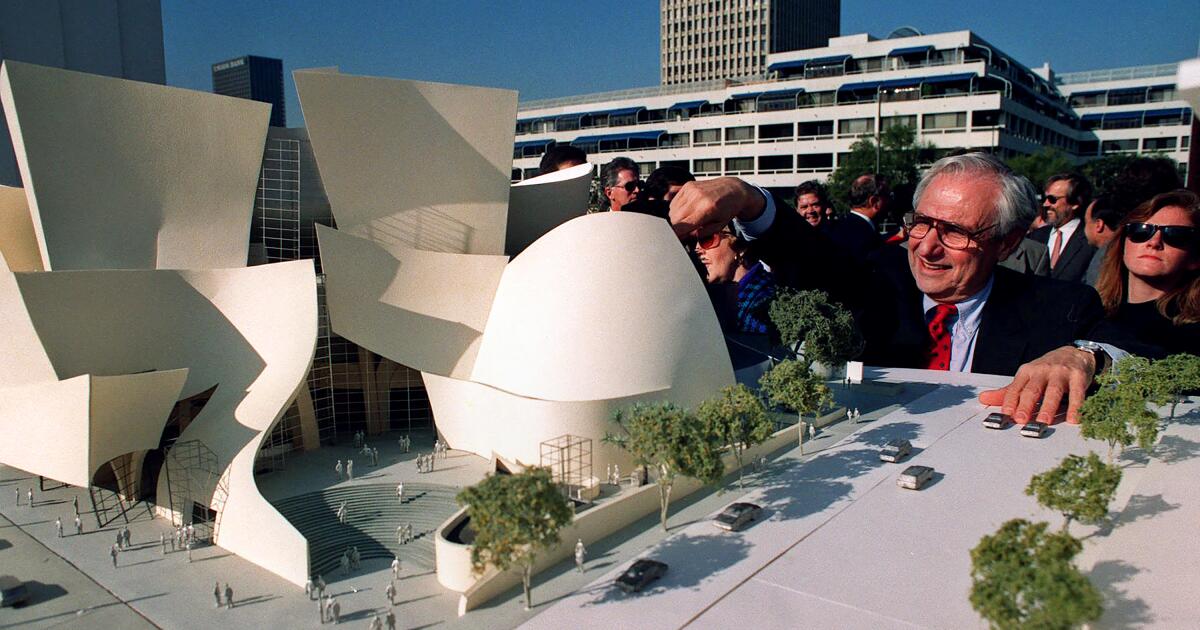

A competition was arranged. Gehry’s model, which was exciting but far more conventional than the masterpiece he ultimately designed, was so superior to the others, especially in its welcoming feeling, that even Gehry’s detractors begrudgingly approved. The four other models, all by distinguished architects, were suspiciously clueless.

I never could get Fleischmann, or anyone else close to the competition, to explain why. Did Fleischmann and others on the jury know all along that Gehry was exactly what the orchestra and the city needed and that the only way to get it was to rig the competition by misleading the other architects? All insisted it was fair. Until evidence proves otherwise, I’m sticking with Fleischmann’s visionary flare eclipsing committee-compromised fair.

The construction site for Disney Hall at 1st Street and Grand Avenue in 1995.

(Carol Cheetham / For The Times)

It would take 16 years to build Disney. Fundraising stalled repeatedly. Gehry’s detractors (including some leading voices at this newspaper) had a field day. The Music Center did not display much enthusiasm.

In the early 1990s, the L.A. riots, the Northridge earthquake and a recession took further wind out of the new hall’s prospective sails. When I arrived at The Times in spring 1996, everyone told me that the hall was moribund. The county, which owns the Music Center and the land on which Disney sits, had built only the parking lot. The county’s supervisors, with the exception of Zev Yaroslavsky, were ready to pull the plug.

But Fleischmann tenaciously hung on. Much later, Esa-Pekka Salonen, then-music director, confessed to me that he had offered his resignation to Fleischmann, in part over his disappointment of the hall’s seeming failure and figuring that maybe another conductor could do more. There was also considerable disgruntlement among board members and patrons over Salonen’s advocacy of new music, despite the fact that he was attracting a younger audience and was increasingly seen as a vital new voice in classical music.

A fundraising deadline loomed, and Fleischmann persuaded Salonen to stick it out a little longer. Just in time, the tide turned, thanks to three fortuitous events. Gehry’s new museum in Bilbao, Spain, wowed the world. A Stravinsky festival that Salonen and the L.A. Phil put on in Paris wowed not only the French but also L.A. Phil board members, including Disney skeptics. The clincher was a series of individual gifts of $5 million each from the publisher of the L.A. Times, then-Mayor Richard Riordan (using his personal money to make what was at the time an anonymous donation) and philanthropist Eli Broad, who then took over the final fundraising.

Disney Hall under construction in 2001.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Disney opened as an instant icon. It catapulted the L.A. Phil to far greater fame than the orchestra had ever known. It spearheaded the revival of downtown and shaped the identity of DTLA, as it would soon be known.

With Disney, the 21st century orchestra was born. The immediacy of the acoustics, the intimate connection between the musicians and listeners, the warmth and visual allure of the interior — all were thrilling. The new hall invited making and consuming new music seem natural. The interior, shaped a little like a ship, put an audience in the mood for adventure.

For the next two decades, the L.A. Phil went from strength to innovative strength, helped by two progressive music directors, Salonen and, beginning in 2009, Dudamel.

Starting with the “Tristan Project” in 2004, Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde,” conducted by Salonen with video by Bill Viola and staged by Peter Sellars, Disney Hall inspired a full expansion of the notion of what classical music could be. The symphony orchestra, with traditions that go back more than three centuries, now had a venue ripe for experimenting with emerging technologies and for incorporating other musical genres and traditions, even other art forms — be they painting, sculpture, dance, theater, performance art, poetry, cinema, video. The L.A. Phil became a model of how an institution could matter, and its home became a tourist attraction, a site to see and a place to be.

Artist Refik Anadol designed projections that lighted up Disney Hall to celebrate the L.A. Phil’s centennial in 2018. Gehry’s original plan for the hall called for live images of the orchestra to be projected on the hall during performances.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

We’ve had a taste of that this season in concerts by Dudamel and Salonen with a range of music, old and memorably new.

At the gala, Dudamel conducted Salonen’s quirky “Fog,” a tribute to Gehry, written five years ago for his 90th birthday. It recalled the first time the composer and conductor heard anything played in the hall while it was under construction.

A few weeks later, Salonen led the premiere of “Tiu,” a big orchestral piece celebrating the hall’s 20th anniversary. Based on the Swedish word for 20, but which also can be Finnish for counting eggs or a musical score, Salonen played with the ordering of 20 chords, turning them into a resplendent phantasmagoric series of dances, fanfares, misty harmonic clouds and melancholic melody.

In what has been an informal festival of Salonen’s scores, the Los Angeles Master Chorale — which has also grown into the big time as the other resident company in Disney — joined the L.A. Phil for Salonen’s wild, dada-inspired “Karawane.”

Dudamel premiered two new works by Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz, the second of which, “Revolución Diamantina” (Glitter Revolution), a five-act ballet score that revolves around the celebrated 2019 feminist march in Mexico City, is relentless in its sonic invention.

Dudamel’s performance of Stravinsky’s “The Firebird,” Salonen’s of Strauss’ “An Alpine Symphony” and Ravel’s “Daphnis and Chloé,” along with Zubin Mehta’s of Mahler’s First Symphony, sounded unlike they might be played by any other orchestra in any other space — namely site specific, an occasion.

Just this month, British composer and part-time Angeleno Thomas Adès introduced his recent “Five Spells From the Tempest.” When Adès conducted the premiere of his second opera, based on Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” at Royal Opera in 2004, shortly after Disney Hall had opened, the London orchestra sounded lackluster in Covent Garden. The opera seemed a misfire and wasn’t all that more impressive when it went to the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Yet Adès’ 22-minute symphonic condensation of the opera score was a knockout when he conducted at Disney.

So it goes. But Disney has also made us complacent. The sorry fact is that the hall has never been the best it can be, and there seems to be far too little motivation to take the place to its necessary next step, almost as if it were 1996 again.

Downtown has not recovered from the pandemic. The Gehry-designed mixed-used development the Grand opened across the street from Disney in fall 2022 but has yet to come to life, struggling to entice restaurants and retail. It has fixtures in which projectors can be installed to create images on Disney. Gehry originally chose a steel skin suitable for projecting video of whatever concert was occurring at night. That’s never happened. He couldn’t get the Music Center to properly light the building at all.

Gustavo Dudamel conducts the L.A. Phil in a modest orchestra pit for Wagner’s “Das Rheingold” in January. Gehry originally wanted the option of a deeper pit, but it was lost in cost-cutting.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Gehry also designed an orchestra pit for the hall that was cut because of cost. Earlier this year, he got a chance to try out that notion with a shallow, makeshift pit created for a staging of Wagner’s “Das Rheingold,” for which the architect also designed sets that essentially turned the whole hall into glorious installation art. Installing a real pit, acoustically tuned, should be a no-brainer.

There are the other long-proposed modifications that include turning BP Hall, where pre-concert talks are held, into a full-fledged chamber music hall, revamping the outdoor amphitheater into an enclosed jazz club and replacing the 1st Street steps with a glass enclosed bar that Gehry would name the Ernest, in honor of Fleischmann.

But who is even around to make that happen? Downtown feels grim. County supervisors show little interest in the Music Center. The new Colburn School concert hall on 2nd Street that Gehry designed has just begun construction after bureaucratic delays. The project’s crucial plaza, though, has been indefinitely postponed. An arts corridor on Grand Avenue surely would, as Disney proved, spark a new DTLA resurgence, but City Hall is not acting like it cares.

As for the Music Center: Over the second weekend this month, I attended Pina Bausch’s “The Rite of Spring” in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and Matthew Bourne’s “Romeo and Juliet” at the Ahmanson Theatre, and I felt like I had wandered back in time.

Bausch’s once supposedly revolutionary Stravinsky ballet, which she choreographed in 1975 when she was just beginning, was included in the first U.S. appearances of her company at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium as part of the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival. Even then, impressive as it was, with magnificently disciplined dancers dashing on a peat-moss floor, it was clear that this was the kind of old-school abstractly modernist ballet that Bausch had outgrown.

Stravinsky’s score to “The Rite” culminated Salonen’s opening night concert for Disney in 2003, and that was all it took to understand what this hall could do. The first recording in Disney was Salonen conducting “The Rite,” and he performed it often enough in the hall, as has Dudamel, that it is a kind of informal Disney theme song.

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

In the Chandler, Bausch’s company played a recording of “The Rite.” Neither the conductor nor the orchestra of the lumbering performance was credited. The recording quality was coarse, and the score was loudly amplified, a solo bassoon in its mysterious high register sounding like a pigeon being tortured. The “Rite” of Disney was terribly wronged.

At the other end of the recently renovated Music Center plaza, bland and lifeless, Bourne brought the 10th of his choreographic productions to the Ahmanson. This take on Prokofiev’s “Romeo and Juliet,” set in a sanatorium with teenagers climbing the walls, has Bourne’s signature clever movement, which can be delightful, and tons of talent onstage.

But how un-Disney to have those gleaming tile walls for a set. Again; the music was recorded, Prokofiev reduced in length and instrumentation, the score sanatorium-sanitized.

In 2018, L.A. choreographer Benjamin Millepied created a site-specific gender-bending version of Prokofiev’s ballet with his L.A. Dance Project for Dudamel and the L.A. Phil. The dance took over Disney — the stage, the seating areas, backstage, the dressing rooms, the garden — as Millepied followed his dancers around with a video camera. Dudamel conducted a soaring performance, and every inch of the hall came to life. Romeo and Juliet weren’t locked away under key, they were among us, their world ours.

That has been the beauty of Gehry’s creation. He wanted it to be our city’s living room, part of our lives. And he left room for more. But we don’t have a Fleischmann. The L.A. Phil is leaderless without a chief executive and with Dudamel’s tenure ending after two more seasons. Who at the Music Center or City Hall can make anything happen? Time is running out. The 2028 Olympics are practically around the corner. Gehry isn’t getting any younger. And it appears that Los Angeles is not getting any wiser.

Frank Gehry looks toward Disney Hall from the Conrad hotel at the Grand across the street.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Entertainment

Stephen A. Smith doubles down on calling ICE shooting in Minneapolis ‘completely justified’

Stephen A. Smith is arguably the most-well known sports commentator in the country. But the outspoken ESPN commentator’s perspective outside the sports arena has landed him in a firestorm.

The furor is due to his pointed comments defending an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent who fatally shot a Minneapolis woman driving away from him.

Just hours after the shooting on Wednesday, Smith said on his SiriusXM “Straight Shooter” talk show that although the killing of Renee Nicole Good was “completely unnecessary,” he added that the agent “from a lawful perspective” was “completely justified” in firing his gun at her.

He also noted, “From a humanitarian perspective, however, why did he have to do that?”

Smith’s comments about the agent being in harm’s way echoed the views of Deputy of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, who said Good engaged in an “act of domestic terrorism” by attacking officers and attempting to run them over with her vehicle.

However, videos showing the incident from different angles indicate that the agent was not standing directly in front of Good’s vehicle when he opened fire on her. Local officials contend that Good posed no danger to ICE officers. A video posted by partisan media outlet Alpha News showed Good talking to agents before the shooting, saying, “I’m not mad at you.”

The shooting has sparked major protests and accusations from local officials that the presence of ICE has been disruptive and escalated violence. Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frye condemned ICE, telling agents to “get the f— out of our city.”

The incident, in turn, has put a harsher spotlight on Smith, raising questions on whether he was reckless or irresponsible in offering his views on Good’s shooting when he had no direct knowledge of what had transpired.

An angered Smith appeared on his “Straight Shooter” show on YouTube on Friday, saying the full context of his comments had not been conveyed in media reports, specifically calling out the New York Post and media personality Keith Olbermann, while saying that people were trying to get him fired.

He also doubled down on his contention that Good provoked the situation that led to her death, saying the ICE agent was in front of Good’s car and would have been run over had he not stepped out of the way.

“In the moment when you are dealing with law enforcement officials, you obey their orders so you can get home safely,” he said. “Renee Good did not do that.”

When reached for comment about his statements, a representative for Smith said his response was in Friday’s show.

It’s not the first time Smith, who has suggested he’s interesting in going into politics, has sparked outside the sports universe. He and journalist Joy Reid publicly quarreled following her exit last year from MSNBC.

He also faced backlash from Black media personalities and others when he accused Democratic Rep. Jasmine Crockett of Texas of using “street verbiage” in her frequent criticisms of President Trump.

“The way that Jasmine Crockett chooses to express herself … Aren’t you there to try and get stuff done instead of just being an impediment? ‘I’m just going to go off about Trump, cuss him out every chance I get, say the most derogatory things imaginable, and that’s my day’s work?’ That ain’t work! Work is, this is the man in power. I know what his agenda is. Maybe I try to work with this man. I might get something out of it for my constituents.’ ”

Movie Reviews

Dead Man’s Wire review: Gus Van Sant tackles true-crime intrigue

In 1977, a man named Tony Kiritsis fell behind on mortgage payments for an Indianapolis, Indiana, property that he hoped to develop into an affordable shopping center for independent merchants. He asked his mortgage broker for more time, but was denied. This enraged him because he suspected that the broker and his father, who owned the company, were conspiring to defraud him by letting the property go into foreclosure and acquire it for much less than market value. He showed up at the offices of the mortgage company, Meridian, for a scheduled appointment regarding the debt in the broker’s office, where he took the broker, Richard O. Hall, hostage, and demanded $130,000 to settle the debt, plus a public apology from the company. He carried a long cardboard box containing a shotgun with a so-called dead man’s wire, which he affixed to Hall as a precaution against police interference: if either of them were shot, tackled, or even caused to stumble, the wire would pull the trigger, blowing Hall’s head off.

That’s only the beginning of an astonishing story that has inspired many retellings, including a memoir by Hall, a 2018 documentary (whose producers were consultants on this movie) and a podcast drama starring Jon Hamm as Tony Kiritsis. And now it’s the best current movie you likely haven’t heard about—a drama from director Gus Van Sant (“Good Will Hunting”), starring Bill Skarsgård as Tony Kiritsis and Dacre Montgomery as Richard Hall. It’s unabashedly inspired by the best crime dramas from the 1970s, including “Dog Day Afternoon,” “The Sugarland Express,” “Network,” and “Badlands,” and can stand proudly alongside them.

From the opening sequence, which scores the high-strung Tony’s pre-crime prep with Deodato’s immortally groovy disco version of “Thus Spake Zarathustra” played on the radio by one of Tony’s local heroes, the philosophical DJ Fred Temple (Colman Domingo); through the expansive middle section, which establishes Tony as part of a thriving community that will see him as their representative in the one-sided struggle between labor and capital; through the ending and postscript, which leave you unsure how to feel about what you’ve seen but eager to discuss it with others, “Dead Man’s Wire” is a nostalgia trip of the best kind. Rather than superficially imitate the style of a specific type of ’70s drama, Van Sant and his collaborators connect with the essence of what made them powerful and memorable: their connection to issues that weighed on viewers’ minds fifty years ago and that have grown heavier since.

Tony is far from a criminal genius or a potential folk hero, but thinks he’s both. The shotgun box with a weird bulge, barely held together with packing tape, is a correlative of the mentality of the man who carries it. His home is filled with counterculture-adjacent books, but he’s a slob who loudly gripes during a brief car ride that his “shorts have been ridin’ up since Market Street,” and has a vanity license plate that reads “TOPLESS.” His eloquence runs the gamut from Everyman acuity to self-canceling nonsense slathered in profanity . He accurately sums up the mortgage company’s practices as “a private equity trap” (a phrase that looks ahead to the 2008 financial collapse, which was sparked by predatory lending on subprime mortgages) and hopes that his extreme actions will generate some “some goddamn catharsis” for himself and his fellow citizens, and “some genuine guilt” among Indianapolis’ lending class.

He’s also intoxicated by his sudden local fame. The hostage situation migrates from the mortgage company to Tony’s shabby apartment complex, which is quickly surrounded by beat cops, tactical officers, and reporters (including Myha’La as Linda Page, a twenty-something, Black local TV correspondent looking to move up. Tony also forces his way into the life of his idol Temple, who tapes a phone conversation with him, previews it for police, and grudgingly accepts their or-else request to continue the dialog and plays their regular talks on his morning show.

Despite these inroads, Tony is unable to prevent his inner petty schmuck from emerging and undermining his message, such as it is. He vacillates between treating Hall as a useless representative of the financial elite (when the elder Hall finally agrees to speak with Tony via phone from a tropical vacation, Tony sneers to Hall the younger, “Your daddy’s on the line—he wants to know when you’ll be home for supper!”) and connecting with him on a human level. When he’s not bombastic, he’s needy and fawning. “I like you!” he keeps telling people he just met, but Fred most of all—as if a Black man who’d built a comfortable life for himself and his wife in 1977 Indiana could say no when an overwhelmingly white police force asked him to become Tony’s fake-confidant; and as if it matters whether a hostage-taking gunman feels warmly towards him.

Ultimately, though, making perfect sense and effecting lasting change are no higher on Tony’s agenda than they were for the protagonists of “Dog Day Afternoon” and “Network.” Like them, these are unhinged audience surrogates whose media stardom turned them into human megaphones for anger at the miserable state of things, and the indifference of institutions that caused or worsened it. These include local law enforcement, which—to paraphrase hapless bank robber Sonny Wirtzik taunting cops in “Dog Day Afternoon”—wanna kill Tony so bad that they can taste it. The discussions between Indianapolis police and the FBI (represented by Neil Mulac’s Agent Patrick Mullaney, a straight-outta-Quantico robot) are all about how to set up and take the kill shot.

The aforementioned phone call leads to a gut-wrenching moment that echoes the then-recent kidnapping of John Paul Getty III, when hostage-takers called their victim’s wealthy grandfather to arrange ransom payment, and got nickel-and-dimed as if they were trying to sell him a used car. The elder Hall is played by “Dog Day Afternoon” star Al Pacino, inspired casting that not only officially connects Tony with Wirtzik but proves that, at 85, Pacino can still bring the heat. The character’s presence creeps into the rest of the story like a toxic fog, even when he’s not the subject of conversation.

With his frizzy grey toupee, self-satisfied Midwest twang, and punchable smirk, Pacino is skin-crawlingly perfect as an old man who built a fortune on being good at one thing, but thinks that makes him a fountain of wisdom on all things, including the conduct of Real Men in a land of women and sissies. After watching TV coverage of Tony getting emotional while keeping his shotgun on Richard, Jr., he beams with pride that Tony shed tears but his own son didn’t. (Kelly Lynch, who costarred in another classic Van Sant film about American losers, “Drugstore Cowboy,” plays Richard, Sr.’s trophy wife, who is appalled at being confronted with irrefutable evidence of her husband’s monstrousness, but still won’t say a word against him.)

Van Sant was 25 during the real-life incidents that inspired this movie. That may partly account for the physical realism of the production, which doesn’t feel created but merely observed, in the manner of ’70s movies whose authenticity was strengthened by letting the main characters’ dialogue overlap and compete with ambient sounds; shooting in existing locations when possible, and dressing the actors in clothes that looked as if they’d been hanging in regular folks’ closets for years. Peggy Schnitzer did the costumes, Stefan Dechant the production design, and Arnaud Poiter the cinematography, all of which figuratively wear bell-bottom pants and platform shoes; the soundscape was overseen by Leslie Schatz, who keeps the environments believably dense and filled with incidental sounds while making sure the important stuff can be understood. It should also be mentioned that the film’s blueprint is an original script by a first-timer, Adam Kolodny, with a bona-fide working class worldview; he wrote it while working as a custodian at the Los Angeles Zoo.

More impressive than the film’s behind-the-scenes pedigree is its vision of another time that unexpectedly comes to seem not too different from this one. It is both a lovingly constructed time machine highlighting details that now seem as antiquated as lithography and buckboard wagons (the film deserves a special Oscar just for its phones) and a wide-ranging consideration of indestructible realities of life in the United States, which are highlighted in such a way that you notice them without feeling as if the movie pointed at them.

For instance, consider Tony’s infatuation with Fred Temple, which peaks when Tony honors his hero by demonstrating his “soul dancing” for his hostage, is a pre-Internet version of what we would now call a “parasocial relationship.” An awareness of racial dynamics is baked into this, and into the film as a whole. Domingo’s performance as Temple captures the tightrope walk that Black celebrities have to pull off, reassuring their most excitable white fans that they understand and care about them without cosigning condescension or behavior that could escalate into harassment. Consider, too, the matter-of-fact presentation of how easy it is for violence-prone people to buddy up to law enforcement officers, especially when they inhabit the same spaces. When Indianapolis police detective Will Grable (Cary Elwes) approaches Tony on a public street soon after the kidnapping, Tony’s face brightens as he exclaims, “Hi Mike! Nice to see you!”

And then, of course, there’s the economic and political framework, which is built with a firm yet delicate hand, and compassion for the vibrant messiness of life. “Dead Man’s Wire” depicts an analog era in which crises like this one were treated as important local matters that involved local people, businesses, and government agents, rather than fuel for a global agitprop industry posing as a news media, and a parasitic army of self-proclaimed influencers reycling the work of other influencers for clout. Van Sant’s movie continually insists on the uniqueness and value of every life shown onscreen, however briefly glimpsed, from the many unnamed citizens who are shown silently watching news coverage of the crisis while working their day jobs, to Fred’s right hand at the radio station, an Asian-American stoner dude (Vinh Nguyen) with a closet-sized office who talent-scouts unknown bands while exhaling cumulus clouds of pot smoke.

All this is drawn together by Van Sant and editor Saar Klein in pop music-driven montages that show how every member of the community depicted in this story is connected, even if they don’t know it or refuse to admit it. As John Donne put it, “No man is an island/Entire of itself/Each is a piece of the continent/A part of the main.” The struggle of the individual is summed up in one of Fred’s hypnotic radio monologues: “Let’s remember to become the ocean, not disappear into it.”

Entertainment

‘Sinners,’ ‘One Battle After Another’ and ‘Hamnet’ among 2026 Producers Guild of America nominees

The Oscar race for best picture came into clearer focus as the Producers Guild of America announced its annual nominees for the Darryl F. Zanuck Award on Friday morning. The 10 nominees (full list below) represent established Oscar-season contenders like “Sinners,” “One Battle After Another,” “Hamnet” and “Marty Supreme,” as well as a handful of films whose awards footing is less certain, including “Weapons,” “F1” and “Bugonia.”

The Producers Guild Awards are considered one of the most reliable bellwethers in the Oscar race because their preferential ballot closely mirrors the academy’s best picture voting system. The PGA Awards have named the future best picture winner in 17 of the last 22 years. Last year, eight of the 10 PGA nominees went on to receive best picture Oscar nominations, including Sean Baker’s “Anora,” which ultimately won both prizes.

Winners will be announced at the PGA’s awards ceremony on Feb. 28 at the Fairmont Century Plaza in Century City.

See the full list of nominees below:

Darryl F. Zanuck Award for outstanding producer of theatrical motion pictures

“Bugonia”

“F1”

“Frankenstein”

“Hamnet”

“Marty Supreme”

“One Battle After Another”

“Sentimental Value”

“Sinners”

“Train Dreams”

“Weapons”

Award for outstanding producer of animated theatrical motion pictures

“The Bad Guys 2”

“Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba Infinity Castle”

“Elio”

“KPop Demon Hunters”

“Zootopia 2”

Norman Felton Award for outstanding producer of episodic television — drama

“Andor”

“The Diplomat”

“The Pitt”

“Pluribus”

“Severance”

“The White Lotus”

Danny Thomas Award for outstanding producer of episodic television — comedy

“The Bear”

“Hacks”

“Only Murders in the Building”

“South Park”

“The Studio”

David L. Wolper Award for outstanding producer of limited or anthology series television

“Adolescence”

“The Beast in Me”

“Black Mirror”

“Black Rabbit”

“Dying for Sex”

Award for outstanding producer of televised or streamed motion pictures

“Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy”

“The Gorge”

“John Candy: I Like Me”

“Mountainhead”

“Nonnas”

Award for outstanding producer of nonfiction television

“aka Charlie Sheen”

“Billy Joel: And So It Goes”

“Mr. Scorsese”

“Pee-wee as Himself”

“SNL50: Beyond Saturday Night”

Award for outstanding producer of live entertainment, variety, sketch, standup and talk television

“The Daily Show”

“Jimmy Kimmel Live!”

“Last Week Tonight with John Oliver”

“The Late Show with Stephen Colbert”

“SNL50: The Anniversary Special”

Award for outstanding producer of game and competition television

“The Amazing Race”

“Jeopardy!”

“RuPaul’s Drag Race”

“Top Chef”

“The Traitors”

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX5 days ago

Dallas, TX5 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health6 days ago

Health6 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Dallas, TX1 day ago

Dallas, TX1 day agoAnti-ICE protest outside Dallas City Hall follows deadly shooting in Minneapolis