Education

Opinion | Parents Don’t Understand How Far Behind Their Kids Are in School

By Tom Kane and Sean Reardon

Graphics by Quoctrung Bui

Dr. Kane is a professor of education and economics at Harvard. Dr. Reardon is a professor of education and sociology at Stanford.

Parents have become a lot more optimistic about how well their children are doing in school.

In 2020 and 2021, a majority of parents in the United States reported that the pandemic was hurting their children’s education. But by the fall of 2022, a Pew survey showed that only a quarter of parents thought their children were still behind; another study revealed that more than 90 percent thought their child had already or would soon catch up. To hear parents tell it, the pandemic’s effects on education were transitory.

Are they right to be so sanguine? The latest evidence suggests otherwise. Math, reading and history scores from the past three years show that students learned far less during the pandemic than was typical in previous years. By the spring of 2022, according to our calculations, the average student was half a year behind in math and a third of a year behind in reading.

Chg. in test score (in years)

Larger circles represent districts with more students.

Before the pandemic, poorer school districts often tested one and a half years below average.

By 2022, the typical district’s math score fell by one half a year.

In the very poorest districts, scores fell by three-quarters of a year.

Note: Average math scores of students in grades three through eight. Source: The Educational Opportunity Project, Stanford University and the Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University

As part of a team of researchers from Harvard, Stanford, Dartmouth, Johns Hopkins and the testing company NWEA — the Education Recovery Scorecard project — we have been sifting through data from 7,800 communities in 41 states, to understand where test scores declined the most, what caused these patterns and whether they are likely to endure. The school districts in these communities enroll 26 million elementary and middle school students in more than 53,000 public schools, roughly 80 percent of the public K-8 students in the country.

We’ve looked at test scores, the duration of school closures, broadband availability, Covid death rates, employment data, patterns of social activity, voting patterns, measures of how connected people are to others in their communities and Facebook survey data on both family activities and mental health during the pandemic.

And to get a sense of how probable it is that students will make up the ground they lost over the next few years, we looked at earlier test scores to see how students recovered from various disruptions in the decade before the pandemic.

Our detailed geographic data reveals what national tests do not: The pandemic exacerbated economic and racial educational inequality.

In 2019, the typical student in the poorest 10 percent of districts scored one and a half years behind the national average for his or her year – and almost four years behind students in the richest 10 percent of districts – in both math and reading.

By 2022, the typical student in the poorest districts had lost three-quarters of a year in math, more than double the decline of students in the richest districts. The declines in reading scores were half as large as in math and were similarly much larger in poor districts than rich districts. The pandemic left students in low-income and predominantly minority communities even further behind their peers in richer, whiter districts than they were.

But while the effects of the pandemic on learning were quite different across communities, they were, surprisingly, evenly distributed among different types of students within each community. You might expect that the more affluent children in a district would be better protected from the educational consequences of the pandemic than their lower-income classmates. But that’s not what we found.

Source: The Educational Opportunity Project, Stanford University and the Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University

Instead, within any school district, test scores declined by similar amounts in all groups of students – rich and poor, white, Black, and Hispanic (we didn’t have enough data on Asian and Native American students to measure their learning). And the extent to which schools were closed appears to have affected all students in a community equally, regardless of income or race.

Overall, it mattered a lot more which school district you lived in than how much money your parents earned.

Once we know that there was much more variation between districts than within them, the obvious question is: Which community factors determined how children were affected? One primary suspect is school closures. And indeed, our study — like other studies, one of which members of the team worked on — shows that test scores declined more in districts where school were closed longer. In districts closed for 90 percent or more of the 2020-21 school year, math scores declined by two-thirds of a year, nearly double the decline in districts that were closed for less than 10 percent of the school year.

But school closures are only part of the story. Students fell behind even in places where schools closed very briefly, at the start of the pandemic in spring 2020, and then re-opened and stayed open for the next few years. Clearly, there were other factors at work.

What were they? We found that test scores declined more in places where the Covid death rate was high, in communities where adults reported feeling more depression and anxiety during the pandemic and where daily routines of children and families were most significantly restricted. In combination, these factors put enormous strain on parents, teachers and kids — making it unlikely that adults could help kids focus on school. Curtailed social activities were particularly harmful: On average, both math and reading scores declined by roughly a tenth of a year more in the 10 percent of districts where social activities were most curtailed than they did in the 10 percent least restricted.

We also found that the test score declines were smaller in communities with high voting rates and high census response rates — indicators of what sociologists call “institutional trust.” School closures were also less harmful in such places.

What all this means is that the educational impacts of the pandemic were not driven solely by what was happening (or not happening) in schools. The disruption in children’s lives outside of school also mattered: the constriction of their social lives, the stress their parents were feeling, the death of family members, the signals that the world was not safe and the very real fear that you or someone you love might get very sick and die. The pandemic was a public health and economic disaster that reshaped every area of children’s lives, but it did so to different degrees in different communities, and so its consequences for children depended on where they lived.

Regardless of how exactly the pandemic caused educational harm, the overall effect has been devastating.

So what do we do now?

Schools cannot just “hurry up.” Especially in math, teachers build students’ understanding sequentially — from arithmetic to fractions to exponents to algebra. Schools have curriculums, and teachers have their lesson plans for each topic. In theory, a school district could rethink its curriculum following a disruption — skimming and paring to move more quickly — but that would be difficult to coordinate across hundreds or thousands of teachers. And do we really want students to have an abbreviated understanding of fractions?

When students fall behind, they don’t just catch up naturally. Reviewing data from the decade preceding the pandemic, we identified numerous instances where a school district’s test scores suddenly declined or suddenly rose in a particular grade. Our data does not reveal the causes. But we can see what happened afterward: Students resumed learning at their prior pace, but they did not make up the ground they lost or lose the ground they gained. Years later, the affected cohorts remained behind or ahead.

Over the past two years, many school districts have used the $190 billion in federal pandemic relief money to add tutors and other school staff and to raise summer school enrollment — all in an attempt to accelerate learning. To a limited extent, they succeeded. In one widely used math and reading assessment, the average student in grades three through eight resumed learning at a slightly faster than normal rate — making up about 25 percent of their pandemic loss in math and reading during the 2021-22 school year and the summer of 2022. But even if schools are able to maintain that pace after the federal dollars to pay for tutors and summer school run out, it will take four years or more to return to pre-pandemic achievement levels.

The truth is children are already paying the price. In the coming weeks, 3.5 million high school seniors are set to graduate — less prepared, on average, for college and a career. They will be joining the more than 10 million students who have already graduated since the pandemic began.

In the hardest-hit communities — where students fell behind by more than one and a half years in math — like Richmond, Va.; St. Louis; and New Haven, Conn. — schools would have had to teach 150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row just to catch up. It is magical thinking to expect they will make this happen without a major increase in instructional time.

For those districts that lost more than a year’s worth of learning, state leaders should require districts to resubmit their plans for spending the federal money and work with them and community leaders to add instructional time.

Parents are relieved to see their children learning again. But most parents remain ill informed about how far behind their children are. To help change that, we’ve made our data public and will continue doing so as new data become available.

Public officials could — and should — help get the word out as well. This summer, mayors and governors should be launching public service campaigns to promote summer learning. And school boards should begin negotiating to extend the next school year (and use the federal dollars to pay teachers for the extra time).

Especially given the mental toll of the pandemic, students need more than math and reading this summer. Rather than school districts trying to do it all themselves, they should link with other organizations — museums, summer camps, athletic programs — that already offer engaging summer programming, and add an academic component to those programs. For instance, Boston After School and Beyond provides an average of $1,500 per student in financial incentives and teaching support to add three hours of academic programming per day from a certified teacher at summer camps enrolling Boston students. The incentives are largely paid for by Boston Public Schools. The program is a potential model for other communities.

While summer learning can be part of a solution, it cannot be the sole solution. Research on programs like the one in Boston suggests that participants make up about one-quarter of a year’s worth of learning in math during a six-week summer program. That takes us part of the way, but nowhere near as far as we need to go.

Communities must find other ways to add learning opportunities outside the typical school calendar. Most educational software — like Zearn and Khan Academy — makes it possible to track students’ use and progress. Schools could incentivize organizations working with students after school, on weekends or during school vacation weeks to include time for students to learn online and then reimburse them based on students’ progress. Some districts are even paying tutoring providers based on student outcomes.

Especially in the hardest-hit communities, it is increasingly obvious that many students will not have caught up before the federal money runs out in 2024. School boards and state legislatures should start planning now for longer-term policy changes. One possibility would be to offer an optional fifth year of high school for students to fill holes in academic skills, get help with applying to college or to explore alternative career pathways. Students could split their time among high schools, community colleges and employers. Another option would be to make ninth grade a triage year during which students would receive intensive help in key academic subjects.

As enticing as it might be to get back to normal, doing so will just leave in place the devastating increase in inequality caused by the pandemic. In many communities, students lost months of learning time. Justice demands that we replace it. We must find creative ways to add new learning opportunities in the summer, after school, on weekends or during a 13th year of school.

If we fail to replace what our children lost, we — not the coronavirus — will be responsible for the most inequitable and longest-lasting legacy of the pandemic. But if we succeed, that broader and more responsive system of learning can be our gift to America’s schoolchildren.

Education

Video: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

new video loaded: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

transcript

transcript

Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

Police officers arrested 33 pro-Palestinian protesters and cleared a tent encampment on the campus of George Washingon University.

-

“The Metropolitan Police Department. If you are currently on George Washington University property, you are in violation of D.C. Code 22-3302, unlawful entry on property.” “Back up, dude, back up. You’re going to get locked up tonight — back up.” “Free, free Palestine.” “What the [expletive] are you doing?” [expletives] “I can’t stop — [expletives].”

Recent episodes in Israel-Hamas War

Education

How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours

A satellite image of the UCLA campus.

On Tuesday night, violence erupted at an encampment that pro-Palestinian protesters had set up on April 25.

The image is annotated to show the extent of the pro-Palestinian encampment, which takes up the width of the plaza between Powell Library and Royce Hall.

The clashes began after counterprotesters tried to dismantle the encampment’s barricade. Pro-Palestinian protesters rushed to rebuild it, and violence ensued.

Arrows denote pro-Israeli counterprotesters moving towards the barricade at the edge of the encampment. Arrows show pro-Palestinian counterprotesters moving up against the same barricade.

Police arrived hours later, but they did not intervene immediately.

An arrow denotes police arriving from the same direction as the counterprotesters and moving towards the barricade.

A New York Times examination of more than 100 videos from clashes at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that violence ebbed and flowed for nearly five hours, mostly with little or no police intervention. The violence had been instigated by dozens of people who are seen in videos counterprotesting the encampment.

The videos showed counterprotesters attacking students in the pro-Palestinian encampment for several hours, including beating them with sticks, using chemical sprays and launching fireworks as weapons. As of Friday, no arrests had been made in connection with the attack.

To build a timeline of the events that night, The Times analyzed two livestreams, along with social media videos captured by journalists and witnesses.

The melee began when a group of counterprotesters started tearing away metal barriers that had been in place to cordon off pro-Palestinian protesters. Hours earlier, U.C.L.A. officials had declared the encampment illegal.

Security personnel hired by the university are seen in yellow vests standing to the side throughout the incident. A university spokesperson declined to comment on the security staff’s response.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

It is not clear how the counterprotest was organized or what allegiances people committing the violence had. The videos show many of the counterprotesters were wearing pro-Israel slogans on their clothing. Some counterprotesters blared music, including Israel’s national anthem, a Hebrew children’s song and “Harbu Darbu,” an Israeli song about the Israel Defense Forces’ campaign in Gaza.

As counterprotesters tossed away metal barricades, one of them was seen trying to strike a person near the encampment, and another threw a piece of wood into it — some of the first signs of violence.

Attacks on the encampment continued for nearly three hours before police arrived.

Counterprotesters shot fireworks toward the encampment at least six times, according to videos analyzed by The Times. One of them went off inside, causing protesters to scream. Another exploded at the edge of the encampment. One was thrown in the direction of a group of protesters who were carrying an injured person out of the encampment.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

Some counterprotesters sprayed chemicals both into the encampment and directly at people’s faces.

Sean Beckner-Carmitchel via Reuters

At times, counterprotesters swarmed individuals — sometimes a group descended on a single person. They could be seen punching, kicking and attacking people with makeshift weapons, including sticks, traffic cones and wooden boards.

StringersHub via Associated Press, Sergio Olmos/Calmatters

In one video, protesters sheltering inside the encampment can be heard yelling, “Do not engage! Hold the line!”

In some instances, protesters in the encampment are seen fighting back, using chemical spray on counterprotesters trying to tear down barricades or swiping at them with sticks.

Except for a brief attempt to capture a loudspeaker used by counterprotesters, and water bottles being tossed out of the encampment, none of the videos analyzed by The Times show any clear instance of encampment protesters initiating confrontations with counterprotesters beyond defending the barricades.

Shortly before 1 a.m. — more than two hours after the violence erupted — a spokesperson with the mayor’s office posted a statement that said U.C.L.A officials had called the Los Angeles Police Department for help and they were responding “immediately.”

Officers from a separate law enforcement agency — the California Highway Patrol — began assembling nearby, at about 1:45 a.m. Riot police with the L.A.P.D. joined them a few minutes later. Counterprotesters applauded their arrival, chanting “U.S.A., U.S.A., U.S.A.!”

Just four minutes after the officers arrived, counterprotesters attacked a man standing dozens of feet from the officers.

Twenty minutes after police arrive, a video shows a counterprotester spraying a chemical toward the encampment during a scuffle over a metal barricade. Another counterprotester can be seen punching someone in the head near the encampment after swinging a plank at barricades.

Fifteen minutes later, while those in the encampment chanted “Free, free Palestine,” counterprotesters organized a rush toward the barricades. During the rush, a counterprotester pulls away a metal barricade from a woman, yelling “You stand no chance, old lady.”

Throughout the intermittent violence, officers were captured on video standing about 300 feet away from the area for roughly an hour, without stepping in.

It was not until 2:42 a.m. that officers began to move toward the encampment, after which counterprotesters dispersed and the night’s violence between the two camps mostly subsided.

The L.A.P.D. and the California Highway Patrol did not answer questions from The Times about their responses on Tuesday night, deferring to U.C.L.A.

While declining to answer specific questions, a university spokesperson provided a statement to The Times from Mary Osako, U.C.L.A.’s vice chancellor of strategic communications: “We are carefully examining our security processes from that night and are grateful to U.C. President Michael Drake for also calling for an investigation. We are grateful that the fire department and medical personnel were on the scene that night.”

L.A.P.D. officers were seen putting on protective gear and walking toward the barricade around 2:50 a.m. They stood in between the encampment and the counterprotest group, and the counterprotesters began dispersing.

While police continued to stand outside the encampment, a video filmed at 3:32 a.m. shows a man who was walking away from the scene being attacked by a counterprotester, then dragged and pummeled by others. An editor at the U.C.L.A. student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, told The Times the man was a journalist at the paper, and that they were walking with other student journalists who had been covering the violence. The editor said she had also been punched and sprayed in the eyes with a chemical.

On Wednesday, U.C.L.A.’s chancellor, Gene Block, issued a statement calling the actions by “instigators” who attacked the encampment unacceptable. A spokesperson for California Gov. Gavin Newsom criticized campus law enforcement’s delayed response and said it demands answers.

Los Angeles Jewish and Muslim organizations also condemned the attacks. Hussam Ayloush, the director of the Greater Los Angeles Area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, called on the California attorney general to investigate the lack of police response. The Jewish Federation Los Angeles blamed U.C.L.A. officials for creating an unsafe environment over months and said the officials had “been systemically slow to respond when law enforcement is desperately needed.”

Fifteen people were reportedly injured in the attack, according to a letter sent by the president of the University of California system to the board of regents.

The night after the attack began, law enforcement warned pro-Palestinian demonstrators to leave the encampment or be arrested. By early Thursday morning, police had dismantled the encampment and arrested more than 200 people from the encampment.

Education

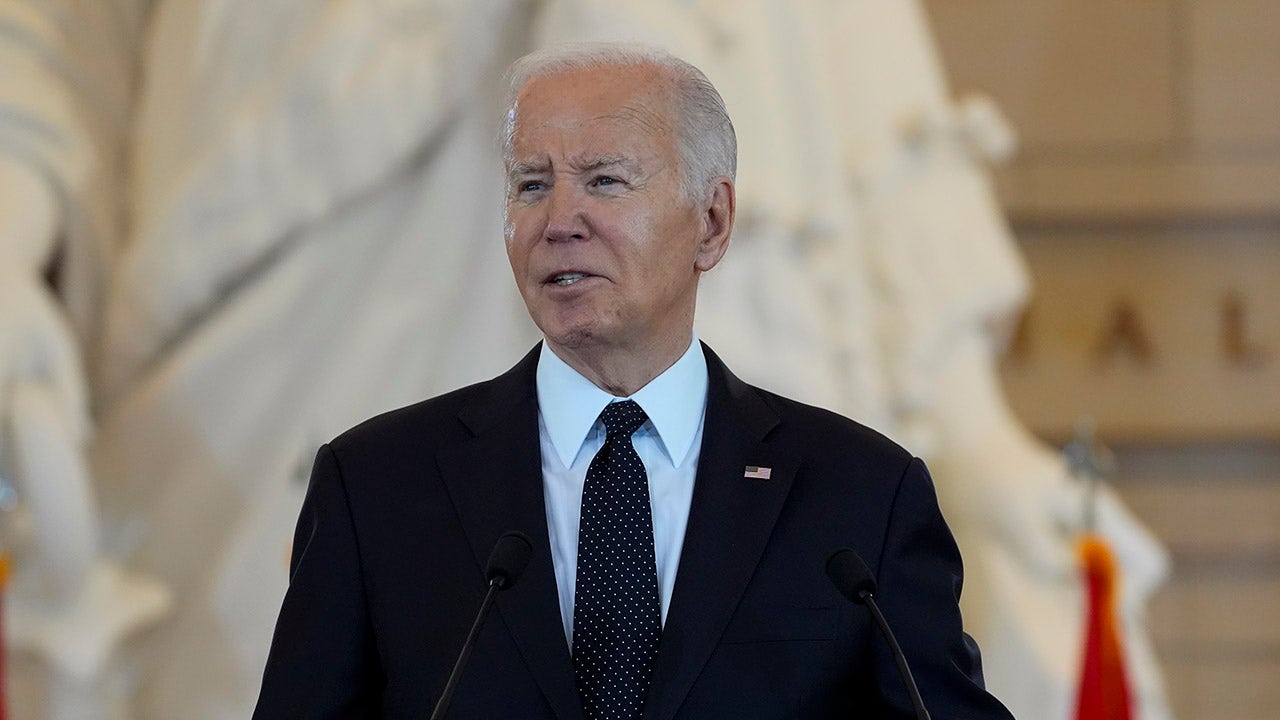

Video: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

new video loaded: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

transcript

transcript

President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

President Biden defended the right of demonstrators to protest peacefully, but condemned the “chaos” that has prevailed at many colleges nationwide.

-

Violent protest is not protected. Peaceful protest is. It’s against the law when violence occurs. Destroying property is not a peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Vandalism, trespassing, breaking windows, shutting down campuses, forcing the cancellation of classes and graduations — none of this is a peaceful protest. Threatening people, intimidating people, instilling fear in people is not peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Dissent is essential to democracy, but dissent must never lead to disorder or to denying the rights of others, so students can finish the semester and their college education. There’s the right to protest, but not the right to cause chaos. People have the right to get an education, the right to get a degree, the right to walk across the campus safely without fear of being attacked. But let’s be clear about this as well. There should be no place on any campus — no place in America — for antisemitism or threats of violence against Jewish students. There is no place for hate speech or violence of any kind, whether it’s antisemitism, Islamophobia or discrimination against Arab Americans or Palestinian Americans. It’s simply wrong. There’s no place for racism in America.

Recent episodes in Politics

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoStrack-Zimmermann blasts von der Leyen's defence policy

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe White House has a new curator. Donna Hayashi Smith is the first Asian American to hold the post

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDemocratic mayor joins Kentucky GOP lawmakers to celebrate state funding for Louisville

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTurkish police arrest hundreds at Istanbul May Day protests

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Police Arrest Columbia Protesters Occupying Hamilton Hall

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewsom, state officials silent on anti-Israel protests at UCLA

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPolice enter UCLA anti-war encampment; Arizona repeals Civil War-era abortion ban