Education

Florida School District Is Sued Over Book Restrictions

A lawsuit filed in federal court on Wednesday said that a Florida county violated the First Amendment by removing or restricting certain kinds of books from its school libraries.

The free-speech organization PEN America and the country’s largest book publisher, Penguin Random House, filed the lawsuit, along with a group of authors and parents. The complaint said that the Escambia County School District and school board also violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution because books they targeted were disproportionately written by nonwhite and L.G.B.T.Q. authors and addressed themes of race, racism, gender and sexuality.

“Today, Escambia County seeks to bar books critics view as too ‘woke,’” said the complaint, filed in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida. “In the 1970s, schools sought to bar ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ and books edited by Langston Hughes. Tomorrow, it could be books about Christianity, the country’s founders or war heroes. All of these removals run afoul of the First Amendment.”

The restrictions the lawsuit is concerned with began when a language-arts teacher at the district’s Northview High School challenged more than 100 titles beginning last year, including picture books, young adult novels and works of nonfiction. The complaint described the teacher’s objections as “nakedly ideological,” saying that she had argued that the books “should be evaluated based on explicit sexual content, graphic language, themes, vulgarity and political pushes.”

Many of the titles the teacher pointed to addressed themes of sexuality, gender identity, race or racism, the complaint said. Among them was “And Tango Makes Three,” about a penguin family with two fathers, which she objected to for “serving an ‘L.G.B.T.Q. agenda using penguins.’”

So far, the school board has voted to remove 10 books, some entirely and others from certain grade levels. In each instance, the board did so despite a recommendation from a district-level committee of educators, media specialists, community members and parents that the books remain in place.

The district has also changed what happens to books while the legal challenge plays out. Traditionally, books would remain on the shelves until after they were evaluated and possibly removed. Now, many of those books are placed in a restricted area that children need parental permission to enter. The lawsuit described the policy as allowing an indefinite restricting of titles and said that entering a special area would be a significant hurdle for a child, one that could come with a certain stigma.

The school board did not immediately respond to a request for comment Wednesday morning. Cody Strother, a spokesman for the Escambia school district, said the district was unable to comment on pending litigation.

Florida has become a hot spot in the dispute over what reading material is appropriate for children. Last year, the state legislature passed three laws regulating educational or reading materials. One prohibits instruction that could make children feel guilty about past actions of members of their race, and another bans instruction on gender identity or sexual orientation. Initially limited to elementary school, the law now applies to all grades. But this debate is not limited to one state.

“Escambia offers a very vivid and disturbing example of what’s happening across the country,” said Suzanne Nossel, chief executive of PEN America, “these politically motivated, ideologically driven, view-point-based bans on books.”

Proponents of book restrictions say they are trying to protect children from inappropriate material and to give parents more say in their children’s education. Many also object to saying that these books are banned because they are still available in public libraries and bookstores. Young people, they say, should encounter sensitive topics with adult supervision, not alone in the school library.

Several authors whose books have been removed or restricted in the district joined the lawsuit, including Sarah Brannen, George M. Johnson, David Levithan, Kyle Lukoff and Ashley Hope Pérez.

Ms. Brannen’s picture book, “Uncle Bobby’s Wedding,” which features a girl whose uncle marries his boyfriend, was challenged in Escambia by a resident who objected to the content because the “book contains alternate sexual ideologies” and “should not be in lower levels in elementary at all,” according to a form that was filled out.

One example of inappropriate content provided in the objection was an illustration that showed Uncle Bobby holding his boyfriend’s hand. Access to the book, which is aimed at 3- to 7-year-olds, has been restricted during the review period, meaning that only students whose parents sign an opt-in form can read it, according to the lawsuit.

“It seems very clear from the nature of the complaints against the books that they are being removed on ideological grounds, and therefore it’s clearly unconstitutional,” Ms. Brannen said. “My book is being restricted because it has L.G.B.T.Q. characters in it.”

Penguin Random House was also part of the suit. Many of its books have been removed from Escambia school libraries or otherwise restricted, including “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, “Push” by Sapphire and “The Kite Runner” by Khaled Hosseini. “We see a rise in these book-banning activities, and we felt compelled to support our authors, our teachers, our librarians, who are on the front lines of these battles on a day-to-day basis,” said Nihar Malaviya, the company’s chief executive.

One of the parents who is suing the district, Lindsay Durtschi, lives in Pensacola and has a 6-year-old and a 9-year-old in school in Escambia. Ms. Durtschi said she volunteered to join the committee that was formed to evaluate books to make sure they complied with new guidelines. She was alarmed to see that the books being scrutinized were mainly about themes of race, gender or sexuality.

“It’s important, as part of their public education, that they are encountering lives that look different from their own,” she said of her own children and other students. “It’s infringing on our students’ First Amendment rights, because even if a book is available in the public library or on the internet, that does not negate the necessity for it to be in the school library, because not every child is privileged to have their parents pick up a library card or to have a tablet or an e-reader.”

Ms. Durtschi said she was particularly upset that two books her 9-year-old daughter loves — “And Tango Makes Three” and “Drama,” a graphic novel about a girl who loves theater — were removed from the school library.

“It’s one thing to say, ‘I don’t want my kid to read that book,’” she said. “But if the book isn’t there, no one can read it.”

Education

Video: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

new video loaded: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

transcript

transcript

Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

Police officers arrested 33 pro-Palestinian protesters and cleared a tent encampment on the campus of George Washingon University.

-

“The Metropolitan Police Department. If you are currently on George Washington University property, you are in violation of D.C. Code 22-3302, unlawful entry on property.” “Back up, dude, back up. You’re going to get locked up tonight — back up.” “Free, free Palestine.” “What the [expletive] are you doing?” [expletives] “I can’t stop — [expletives].”

Recent episodes in Israel-Hamas War

Education

How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours

A satellite image of the UCLA campus.

On Tuesday night, violence erupted at an encampment that pro-Palestinian protesters had set up on April 25.

The image is annotated to show the extent of the pro-Palestinian encampment, which takes up the width of the plaza between Powell Library and Royce Hall.

The clashes began after counterprotesters tried to dismantle the encampment’s barricade. Pro-Palestinian protesters rushed to rebuild it, and violence ensued.

Arrows denote pro-Israeli counterprotesters moving towards the barricade at the edge of the encampment. Arrows show pro-Palestinian counterprotesters moving up against the same barricade.

Police arrived hours later, but they did not intervene immediately.

An arrow denotes police arriving from the same direction as the counterprotesters and moving towards the barricade.

A New York Times examination of more than 100 videos from clashes at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that violence ebbed and flowed for nearly five hours, mostly with little or no police intervention. The violence had been instigated by dozens of people who are seen in videos counterprotesting the encampment.

The videos showed counterprotesters attacking students in the pro-Palestinian encampment for several hours, including beating them with sticks, using chemical sprays and launching fireworks as weapons. As of Friday, no arrests had been made in connection with the attack.

To build a timeline of the events that night, The Times analyzed two livestreams, along with social media videos captured by journalists and witnesses.

The melee began when a group of counterprotesters started tearing away metal barriers that had been in place to cordon off pro-Palestinian protesters. Hours earlier, U.C.L.A. officials had declared the encampment illegal.

Security personnel hired by the university are seen in yellow vests standing to the side throughout the incident. A university spokesperson declined to comment on the security staff’s response.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

It is not clear how the counterprotest was organized or what allegiances people committing the violence had. The videos show many of the counterprotesters were wearing pro-Israel slogans on their clothing. Some counterprotesters blared music, including Israel’s national anthem, a Hebrew children’s song and “Harbu Darbu,” an Israeli song about the Israel Defense Forces’ campaign in Gaza.

As counterprotesters tossed away metal barricades, one of them was seen trying to strike a person near the encampment, and another threw a piece of wood into it — some of the first signs of violence.

Attacks on the encampment continued for nearly three hours before police arrived.

Counterprotesters shot fireworks toward the encampment at least six times, according to videos analyzed by The Times. One of them went off inside, causing protesters to scream. Another exploded at the edge of the encampment. One was thrown in the direction of a group of protesters who were carrying an injured person out of the encampment.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

Some counterprotesters sprayed chemicals both into the encampment and directly at people’s faces.

Sean Beckner-Carmitchel via Reuters

At times, counterprotesters swarmed individuals — sometimes a group descended on a single person. They could be seen punching, kicking and attacking people with makeshift weapons, including sticks, traffic cones and wooden boards.

StringersHub via Associated Press, Sergio Olmos/Calmatters

In one video, protesters sheltering inside the encampment can be heard yelling, “Do not engage! Hold the line!”

In some instances, protesters in the encampment are seen fighting back, using chemical spray on counterprotesters trying to tear down barricades or swiping at them with sticks.

Except for a brief attempt to capture a loudspeaker used by counterprotesters, and water bottles being tossed out of the encampment, none of the videos analyzed by The Times show any clear instance of encampment protesters initiating confrontations with counterprotesters beyond defending the barricades.

Shortly before 1 a.m. — more than two hours after the violence erupted — a spokesperson with the mayor’s office posted a statement that said U.C.L.A officials had called the Los Angeles Police Department for help and they were responding “immediately.”

Officers from a separate law enforcement agency — the California Highway Patrol — began assembling nearby, at about 1:45 a.m. Riot police with the L.A.P.D. joined them a few minutes later. Counterprotesters applauded their arrival, chanting “U.S.A., U.S.A., U.S.A.!”

Just four minutes after the officers arrived, counterprotesters attacked a man standing dozens of feet from the officers.

Twenty minutes after police arrive, a video shows a counterprotester spraying a chemical toward the encampment during a scuffle over a metal barricade. Another counterprotester can be seen punching someone in the head near the encampment after swinging a plank at barricades.

Fifteen minutes later, while those in the encampment chanted “Free, free Palestine,” counterprotesters organized a rush toward the barricades. During the rush, a counterprotester pulls away a metal barricade from a woman, yelling “You stand no chance, old lady.”

Throughout the intermittent violence, officers were captured on video standing about 300 feet away from the area for roughly an hour, without stepping in.

It was not until 2:42 a.m. that officers began to move toward the encampment, after which counterprotesters dispersed and the night’s violence between the two camps mostly subsided.

The L.A.P.D. and the California Highway Patrol did not answer questions from The Times about their responses on Tuesday night, deferring to U.C.L.A.

While declining to answer specific questions, a university spokesperson provided a statement to The Times from Mary Osako, U.C.L.A.’s vice chancellor of strategic communications: “We are carefully examining our security processes from that night and are grateful to U.C. President Michael Drake for also calling for an investigation. We are grateful that the fire department and medical personnel were on the scene that night.”

L.A.P.D. officers were seen putting on protective gear and walking toward the barricade around 2:50 a.m. They stood in between the encampment and the counterprotest group, and the counterprotesters began dispersing.

While police continued to stand outside the encampment, a video filmed at 3:32 a.m. shows a man who was walking away from the scene being attacked by a counterprotester, then dragged and pummeled by others. An editor at the U.C.L.A. student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, told The Times the man was a journalist at the paper, and that they were walking with other student journalists who had been covering the violence. The editor said she had also been punched and sprayed in the eyes with a chemical.

On Wednesday, U.C.L.A.’s chancellor, Gene Block, issued a statement calling the actions by “instigators” who attacked the encampment unacceptable. A spokesperson for California Gov. Gavin Newsom criticized campus law enforcement’s delayed response and said it demands answers.

Los Angeles Jewish and Muslim organizations also condemned the attacks. Hussam Ayloush, the director of the Greater Los Angeles Area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, called on the California attorney general to investigate the lack of police response. The Jewish Federation Los Angeles blamed U.C.L.A. officials for creating an unsafe environment over months and said the officials had “been systemically slow to respond when law enforcement is desperately needed.”

Fifteen people were reportedly injured in the attack, according to a letter sent by the president of the University of California system to the board of regents.

The night after the attack began, law enforcement warned pro-Palestinian demonstrators to leave the encampment or be arrested. By early Thursday morning, police had dismantled the encampment and arrested more than 200 people from the encampment.

Education

Video: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

new video loaded: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

transcript

transcript

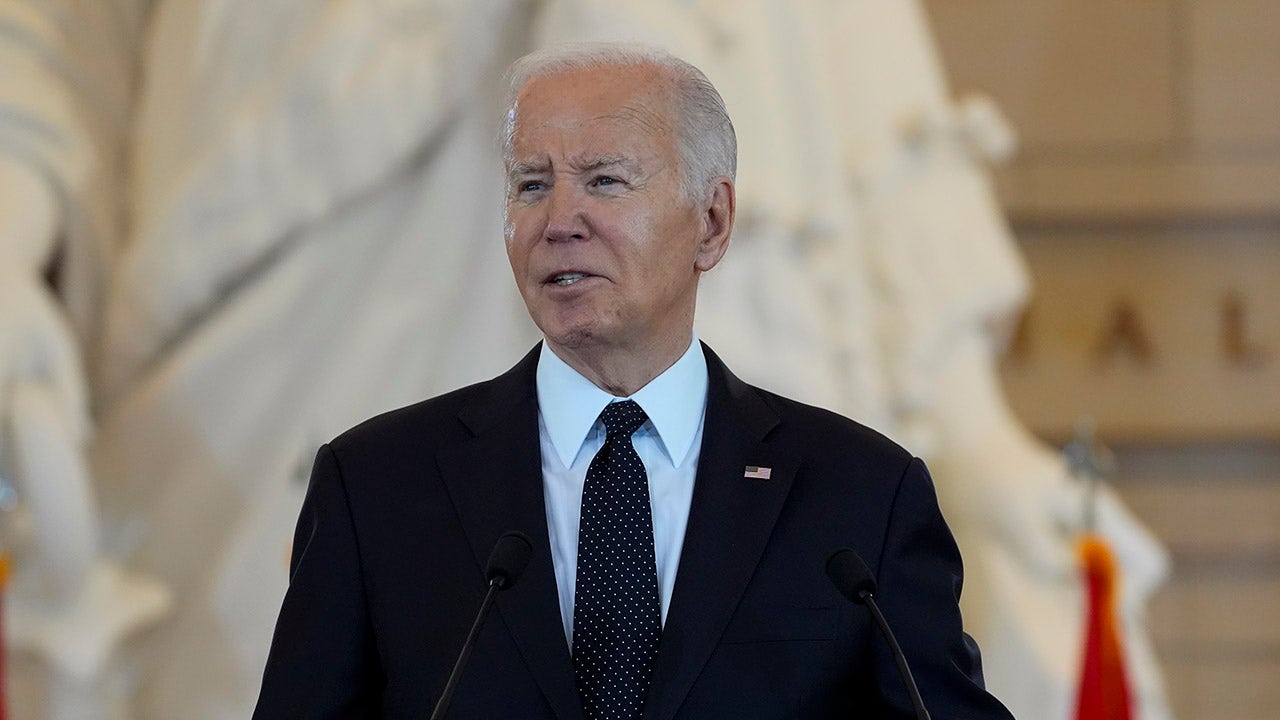

President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

President Biden defended the right of demonstrators to protest peacefully, but condemned the “chaos” that has prevailed at many colleges nationwide.

-

Violent protest is not protected. Peaceful protest is. It’s against the law when violence occurs. Destroying property is not a peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Vandalism, trespassing, breaking windows, shutting down campuses, forcing the cancellation of classes and graduations — none of this is a peaceful protest. Threatening people, intimidating people, instilling fear in people is not peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Dissent is essential to democracy, but dissent must never lead to disorder or to denying the rights of others, so students can finish the semester and their college education. There’s the right to protest, but not the right to cause chaos. People have the right to get an education, the right to get a degree, the right to walk across the campus safely without fear of being attacked. But let’s be clear about this as well. There should be no place on any campus — no place in America — for antisemitism or threats of violence against Jewish students. There is no place for hate speech or violence of any kind, whether it’s antisemitism, Islamophobia or discrimination against Arab Americans or Palestinian Americans. It’s simply wrong. There’s no place for racism in America.

Recent episodes in Politics

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoStrack-Zimmermann blasts von der Leyen's defence policy

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe White House has a new curator. Donna Hayashi Smith is the first Asian American to hold the post

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoStefanik hits special counsel Jack Smith with ethics complaint, accuses him of election meddling

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDemocratic mayor joins Kentucky GOP lawmakers to celebrate state funding for Louisville

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTurkish police arrest hundreds at Istanbul May Day protests

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Police Arrest Columbia Protesters Occupying Hamilton Hall

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewsom, state officials silent on anti-Israel protests at UCLA

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPolice enter UCLA anti-war encampment; Arizona repeals Civil War-era abortion ban