Business

Patt Morrison: Will L.A. ever produce more gimmicky, lovable pitchmen like Cal Worthington?

There is no patron saint of Los Angeles pitchmen, and really, there should be.

After all, ad astra per huckstera — to the stars through salespitchery, right? The job is open, as are the nominations.

An early favorite, and a standard setter even in L.A.’s strenuous real estate game, is Harry Culver. He was the 20th century whiz-bang who parlayed a $2,000 option on 93 acres of barley fields and sales gimmicks and stunts into land deals that begat the city he — modesty be damned — named for himself.

This mantle of commercial sainthood is reserved for those characters who invested their identity and personality — faked or authentic — in their schtick. Disembodied voiceover announcers are not in the running. Let us not speak of them in the same category as true pitchmen. A longevity trophy may have to go to an Orange County dealership’s jingle that “You won’t get a lemon from Toyota of Orange,” even though it mangles the two citric syllables of “orange” into a single ugly one — “ornj.” It’s been on the airwaves for about 50 years — almost as long as California has had its pioneering Lemon Law protecting us from getting stuck with junkers.

And if there were a trophy for the ad getting the most and fastest hits on the mute button, the Kars4Kids jingle would likely own it. The Jewish children’s charity has burrowed into the national brainpan for more than 10 years and attracted government scrutiny for its charitable disbursements. This summer, its CEO went to court against New York’s concealed carry gun law, arguing that it leaves Jewish children vulnerable to antisemitic attacks.

Now, for the real candidates for the choicest place in our pitchman pantheon.

Almost all of them are car salesmen, for manifold reasons. The first reason, after World War II, the biggest car market in this big, world-saving nation was in Southern California. The second, that thrive-or-die market demanded that you make a name for yourself, or you get out of the game.

In the 1950s, the game was delivering some self-inflicted wounds. Dirty-dealing practices like “boraxing” — advertising cars that didn’t exist — and rolling back odometers seemed like S.O.P. “Every speedometer was flipped back,” is how a Beverly Hills Studebaker salesman named William L. Plunkett described that “common” practice from the 1950s.

The low ebb came in 1957, when an L.A. County grand jury heard testimony about fudged contracts and trade-in scams, and indicted a dealer and more than a dozen of his associates. The dealer was H.J. Caruso, the father of future L.A. businessman, philanthropist and former mayoral candidate Rick Caruso. The elder Caruso pleaded guilty to what he thought was a deal for a misdemeanor, but there was no such deal, and Caruso and his lawyer couldn’t get the plea changed. Caruso went to jail for a year and was on probation until 1970, when his plea was changed to not guilty and the case was dismissed.

So the gimmicks got schtickier, more frantic, and more desperate to claim the honor of honest, sincere, authentic — and entertaining.

But first, the non-car-dealer contenders.

Earl Scheib

You can pinpoint when you came to live in L.A. by the price that you first remember Scheib advertising to paint your car — from $24.95 in the 1960s to $119.95 by the time he died in 1992. He was the face, and voice, of his business. “I’m Earl Scheib. I’ll paint any car for only (fill in the price here) — no ups, no extras.” He developed a singular painting technique that extended his empire to many states and Europe. Henry Ford once said that a customer could order a Model T in any color, so long as it was black. Scheib’s special offer was good only for a few basic colors, and that special price wasn’t special, just the everyday charge. And the law, in its civil form, like the Federal Trade Commission, had a few words about what Scheib could and could not do in his ads. Scheib’s pitch line earned him a spot on the chair in pitchman’s Valhalla — next to Johnny Carson and his big desk on national TV. He created his own TV spots and told the TV stations running his ads the precise moment he wanted them to interrupt the late movie at a suspenseful moment and drop them in.

How a man born in San Francisco and spending his life in L.A. spoke with a kind of modified Panhandle twang is as much a mystery as the generation of commercial airline pilots who delivered their cockpit patter in Chuck Yeager’s West Virginia cadences.

Larry the mattress guy and Irwin, his beleaguered accountant

Mattress shopping is almost as bewildering and unpleasant as car shopping. Selling a personality gimmick surely catches a buyer’s ear better than some ad comparing models and prices. Although Larry’s accelerando warble pledge from the 1990s kind of does that — “We’ll beat anyone’s advertised price or your mattress is … FREEEEEE!” — it’s the spousal-style ”You’re killing me, Larry” bickering over discount prices that has drilled this bit into your brain. The Larry and Irwin characters are the mattress company owner and L.A. native Larry Miller, and his childhood friend and a real accountant, Irwin Sigmond. As befits a family-owned company, Irwin and Larry’s dynamic became “The Honeymooners” of radio ads.

Ron Popeil

Ron Popeil, the man behind late-night, rapid-fire TV commercials, at his office in Beverly Hills in a file photo.

(Reed Saxon / Associated Press)

If you ever stayed up late with a sick baby or woke up way too early with a bad hangover, Ron Popeil probably kept you company. In his groundbreaking infomercials, he was a master of the art of selling solutions in search of problems. Who knew you absolutely couldn’t live without his Pocket Fisherman, or Veg-o-Matic, or Mr. Microphone, until Popeil told you so? People needed cars, but Popeil had to create a need for his aspirational gadgetry. And for decades he did — so brilliantly that his place in pop culture may last longer than his adman innovations. SNL sent him up when Dan Aykroyd dropped a fish into a “Bass-o-Matic” blender.

If you were about to write a letter to the editor to let me know I forgot Popeil’s “But wait, there’s more” line — don’t. That come-on was the creation of Arthur Schiff, the father of the Ginsu knife and myriad other direct-marketed gizmos, and the developer of that most identifiably infomercial line, which of course made its way into his obituary.

Miss Cleo

Not many women got into the pitchman game, but Youree Dell Harris, born and brought up right here in Los Angeles yet claiming Jamaica as her native land and accent, became a TV meme from the 1990s as the midnight psychic Miss Cleo (“Call me now!”).

She brought in big money for the company that put her on the air, until those businesses were sued by the Federal Trade Commission for defrauding people, and had to hand back a half-billion dollars to customers and stop peddling psychic services by telephone. The hallmark of a true TV pitchperson meme — parodies and a documentary.

And now for the top contenders, the car salesmen — a sampling, FYI, not an encyclopedia entry.

Les and Roger Bacon

Their Hermosa Beach Ford dealership flourished from the ’40s into the ’60s. The slogan was “Get off your couch and get on down to Les Bacon Ford,” but that was meek compared to the family’s ad antics — bashing an old car with a bat and wham knocking the price down $100 wham for every bang. In trade, the Bacons once took a cemetery lot, some land in San Bernardino, and a newspaper printed on the day Lincoln died, April 15, 1865. The Easy Reader obituary for Roger Bacon reported that he’d once offered a free new Ford to anyone who would perch atop a 60-foot pole for 30 days. When one daring man reached Day 29, Bacon sent up word that the man’s wife was in a bar across the street with another man — and the pole sitter abandoned his post.

Tony Holzer

A man of many car incarnations, Holzer was once the “Honest John” dealer, decked out in white robes, wings and an illuminated halo. In another character, he was, probably briefly, “Hog Wild Tony Holzer, a Bundle of Bedlam in Beverly Hills.” Holzer was a Dutch American who once sued a man named Giuliana to settle their argument over who was entitled to sell cars under the name “the smiling Irishman.”

Victor Snyder

Trader Vic’s Pacoima car lot sold “Miracle Cars,” with the honesty-adjacent slogan “If it’s a good car, it’s a Miracle.” Good to his stage name, he took trade-ins, among them a set of golf clubs and a dog he became devoted to. He did business out of a 1918 adobe gas station and handed out lollipops to his customers’ kids. Like the big guys, he too has his own documentary, from 1975.

Chick Lambert and Fletcher Jones

Not partners, but both used dogs as their ad schtick. Lambert always appeared with Storm — always a German shepherd, but, a la Lassie, not always the same German shepherd. And Jones in 1946 opened a used car lot in downtown L.A. In his TV spots, he cuddled a puppy — again, not always the same puppy — and his ads promised that some of your cash on the barrelhead would go to save the lives of cutie pets like this one. Today Fletcher Jones dealerships sell Toyotas in Carson and Mercedes-Benz “motorcars” in Newport Beach.

Frank Taylor

Taylor’s downtown dealership did a bang-up business with Christian churchgoers because his ads vowed, “No Sunday selling.” What Taylor did not reveal, a PR man later did: that he leased his site from a church that wouldn’t permit any Sabbath business. So Taylor turned necessity into a virtue.

‘Crazy Car Men’

Honorable mention to Steve and Curtis at Willowbrook Chrysler for grabbing for the wacky glory of yore days with parody spots; in one, a salesman in a hospital gown says his prices are so low he’s had to sell a kidney to make ends meet. I would be gobsmacked if these were ever broadcast anywhere much beyond Facebook and YouTube.

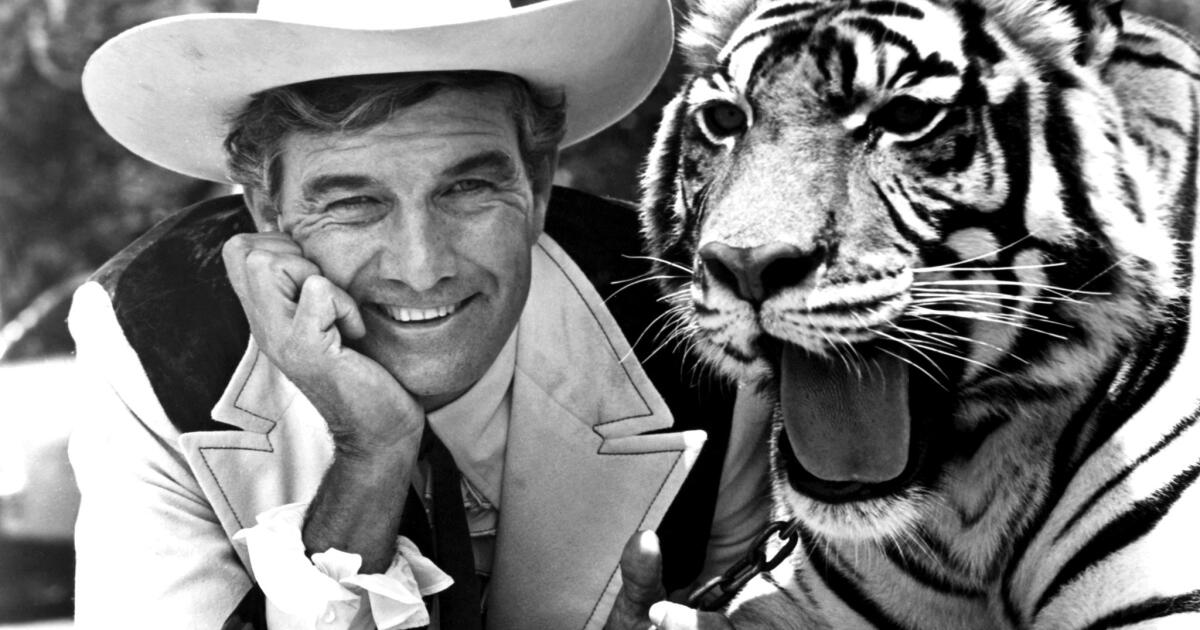

Calvin Coolidge Worthington

Car dealer Cal Worthington records a TV commercial in 1974 with his “dog” Spot.

(Marianna Diamos / Los Angeles Times)

And now we get to the heavyweights.

As chatty as President Coolidge was monosyllabic, Cal Worthington spent as much as $2.5 million a year on advertising that, in his platinum years, put him and his “Go see Cal” jingle on television a thousand times a week, mostly from dusk to dawn.

His original joke, making fun of his dog-hugging competitors above, became his signature line: “my dog Spot,” who was never, ever a dog. A hippopotamus, a coati, a penguin, a gorilla chained to a car bumper, and a goose who once crapped on Worthington’s lap right there on Johnny Carson’s show. Once, Worthington rode Shamu the SeaWorld orca like a bronco.

He never really liked cars, he told me once; “I got trapped in the car business.” But it made him rich, and for an Osage County, Okla., boy who made his Scarlett O’Hara vow that he’d never be hungry again, that was a compromise he gladly made. Worthington came here in 1949, and in time he had dealerships from Anchorage to Phoenix, and piloted his own plane to most of them. It was planes that he loved, and he flew more than two dozen combat missions in World War II, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross.

He told The Times in 1979 that electric cars were the future — clean, quiet and “up to 200 miles on one charge.” But in 2002 he went to Sacramento to lobby against a bill to rein in CO2 emissions from cars.

When TV airtime was cheap, he’d riff for three or four minutes, telling cornpone jokes, extolling the virtues of his “Fords, Shivvys and Tyotas,” and promising to eat a bug if he couldn’t make a deal. But getting squeezed into a 30-second spot was not to his liking — and it probably wasn’t worth whatever he had to pay to rent the hippo.

In 1978, state and federal regulators went after his dealerships, accusing them of deceptive advertising like bait-and-switch tactics, altering smog devices to improve performance and selling as “beautiful, clean and sharp” cars that were “in generally poor condition [with] exceptionally high mileage.” Worthington settled four years later without admitting doing anything wrong. He was married and divorced four times; his eldest child was old enough to be grandfather to his youngest. He liked pretty women, he said, and French Champagne, and babies, and yes — dogs.

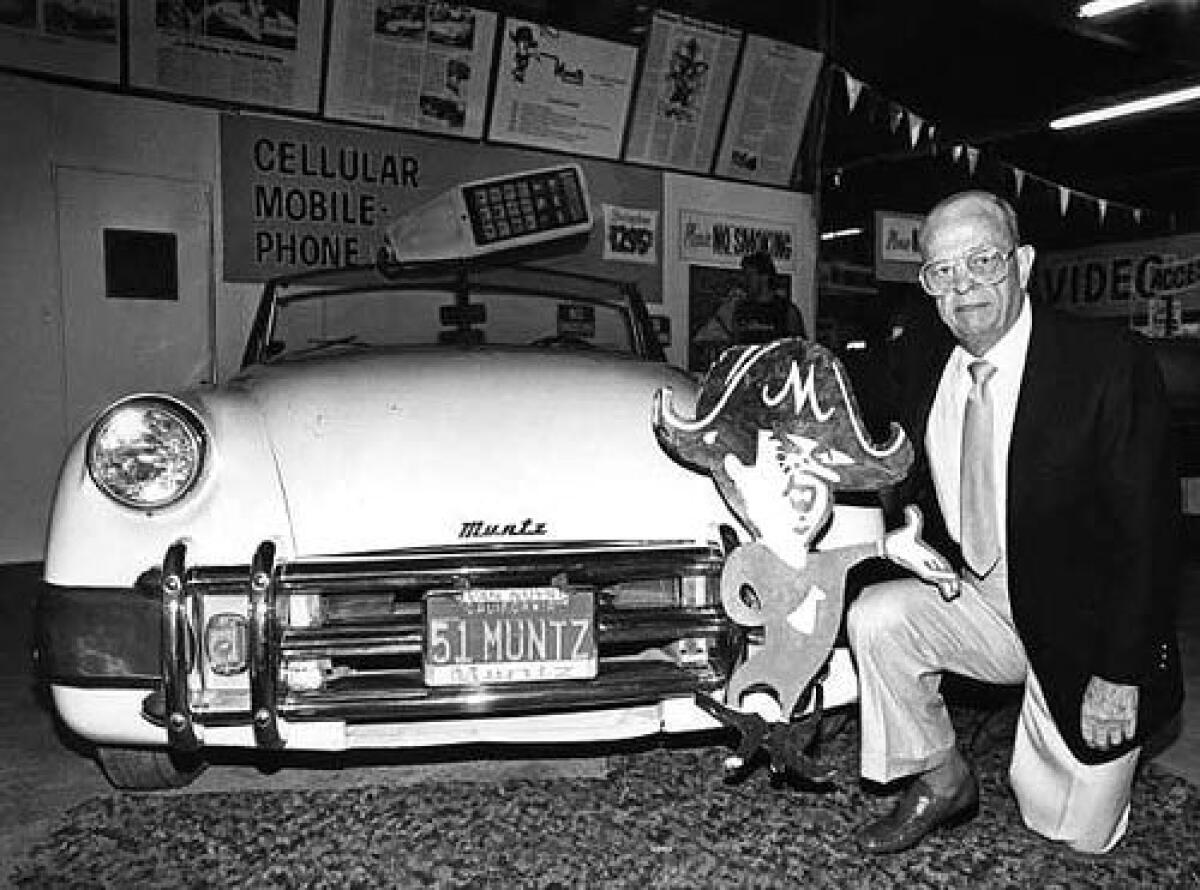

Earl ‘Madman’ Muntz

Earl “Madman” Muntz poses with his Napoleonic mascot and one of his Muntz Jet automobiles.

(Los Angeles Times)

Earl Muntz was the brilliant Barnum of pitchmen, a man who made and lost several fortunes, only one of them selling cars. He came to L.A. in the 1930s, selling from “used car row” on Figueroa. He bought 176 radio spots a day on 13 stations, but the free promotions he got dwarfed that; radio joke writers worked him into scripts for Groucho Marx, Jack Benny, Red Skelton and Abbott and Costello. Bob Hope mentioned him 32 times in 39 shows. There was even a Muntz joke in the Katharine Hepburn-Spencer Tracy movie “State of the Union.”

What was mad about the Madman? He and his cartoon avatar dressed in red long johns and a Napoleon bicorne hat. Crazy like a fox: In 1947 he grossed $72 million in car sales. “We buy ‘em retail and sell ‘em wholesale — more fun that way,” was one of his slogans.

Then, into the 1950s, he manufactured a television set with a larger screen than most, and broke the price floor by selling it for under $100. “I want to give ‘em away, but Mrs. Muntz won’t let me. She’s crazy!” his ads burbled. He mailed TV knobs by the hundreds to Angelenos, with a note telling them to call and he’d bring over the rest of the set. In one year he sold $55 million in TV sets.

He named his daughter TeeVee, although his wife — the final tally was seven — changed it later to Teena. Color TV did in the Muntz TV, but he moved right along to car stereos and his own four-track tape. He bought a Capitol Records catalogue for $75,000 to put music in those tape decks. In 1967, he sold 30 million car stereos and tapes. He made money and went broke and made money again.

His dumbest business move — saying no to the chance to be the U.S. distributor for a funny little car called the Volkswagen. “I drove the car and didn’t like it. I still don’t like it, but I was a damned fool to turn it down.”

He started a business selling kits for prefabricated stamped aluminum houses, sold 11, and closed up shop. He started renting RVs to travelers, and that went bust when they broke down out in the vastness of the American heartland.

His most personal failure has become an oddball success. He designed a high-concept American luxury sports car, the “Muntz Jet.” It was ahead of its time in many ways, with seat belts, a padded dashboard and a backseat liquor cabinet. He had them painted in crayon-brights straight out of the “Barbie” movie — purple, yellow, pink, red — with his Napoleon caricature on the hubcaps. He made fewer than 400 of them. They cost about $6,500 to make and he sold them for $5,500, to very few takers. Today, if you can find one, they can fetch a price nudging six figures.

Broke or flush, Muntz had swagger, all right. In the thick of the Red Scare, he asked an advisor whether he should announce that he was a communist, just for the headlines he’d get. He dated famous women and befriended famous men. He was relentlessly charming, always questing for the new and novel, and living large and lively. He drank highballs, smoked Luckys and drove a custom Lincoln with a TV and VCR in the dashboard. In the documentary “Madman Muntz: American Maverick,” actress Angie Dickinson said his funeral was “one of the funniest funerals I’ve ever been at.”

Could we have a Worthington or Muntz type today?

That kind of universal grip on the public’s mental scenery — it probably can’t happen anymore. The audience is too fragmented, spread too thin across a fractured media landscape for any catchphrase, any peddler, however inventive, to reach this scale of recognition. Muntz and Worthington were big; it’s the airtime that got small.

The only possible new contender I’ve heard recently — and there may be others, in alternate universes of TV and radio that I don’t see or hear, which proves the point I just made — the only possible contender I’ve heard lately is on terrestrial radio. His name is Aaron Adirim, an émigré from Latvia with an MFA from NYU, and a pitchman for his own California window installation business.

His signature slogan is a bit wordy, but delivered with verve and sincerity, which makes sense because he wrote it: “Our installation technique is so precise, we do not break your stucco.” And here comes the earworm: “Your house could be covered with potato chips, and we wouldn’t break one.”

It’s good, but can it bear the tests of time and fickle audiences? Will he too have to eat a bug to make a deal and stay in our brains? Or maybe just eat that stucco?

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Business

L.A. wildfire victims uncertain about returning to their burned neighborhoods

A new survey of victims of the Palisades and Eaton fires shows most would like to return to their old neighborhoods, but they’re worried that government officials can’t make it happen soon enough.

The vast majority of burned-out homeowners surveyed said they intend to rebuild the homes destroyed in the devastating January fires — yet half say they are unwilling to wait more than three years to return.

Urgency on all fronts is paramount to a successful revival of the lost neighborhoods, Los Angeles real estate developer Clare De Briere said.

She helped oversee the survey conducted by Project Recovery, a group of public and private real estate experts who compiled a report in March on what steps can be taken to speed revival as displaced residents weigh their options to return to Pacific Palisades, Altadena, Malibu and other affected neighborhoods.

The report was compiled by professors in the real estate graduate schools at USC and UCLA, along with the Los Angeles chapter of the Urban Land Institute, a real estate nonprofit education and research institute.

For the follow-up survey, Project Recovery tracked down nearly 350 homeowners who experienced total loss or significant damage to their properties to determine their preferences for the future. Most would like to return, but are skeptical about their chances to get back in the near future and will only wait so long before settling in elsewhere.

“For every year it takes to at least start the rebuilding, 20% of the population will find another another place to go,” De Briere said. “If that statistic is right, then after five years, you’re going to have a whole new community there, so it won’t be the same.

“You won’t have the same people remembering the same parades and the same soccer teams, or the librarian who used to have story hour in the local library. All that sort of cultural memory gets, gets wiped out,” she said.

The Project Recovery report outlines a plan to get homes rebuilt within three years after the land is cleared for redevelopment, but it requires close, constant cooperation between builders and public officials overseeing construction approval and restoration of infrastructure such as water and power.

In the recent survey, the top concern of displaced homeowners “was about the lack of leadership, both on the city and the county side to get it done,” she said.

That response came as a surprise to De Briere, who expected affordability to be the chief concern, since many homeowners are indeed worried that they won’t have enough money to rebuild the way they want.

But it typically takes up to 18 months to get a building permit in Los Angeles, a process that needs to be reduced to one to two months, Project Recovery said.

That would require using an expedited process being explored by Los Angeles officials that would allow licensed architects, engineers and design professionals to “self-certify” building plans and specifications as compliant with objective building code requirements. Artificial intelligence could crosscheck their assertions far faster than human staff would be able to do it.

Other major concerns among homeowners surveyed was that rebuilding would take too long and that their communities may never be the same.

Homeowners also worry about being in a fire zone or a landslide zone, she said.

The report authors hope that the rebuilding process will bring better knowledge about managing the ways homes interact with the potentially combustible environment around them.

“If we don’t do it differently, we’re going to have the same thing happen in Beverly Hills, and Bel Air, in Silver Lake, Los Feliz and Echo Park,” De Briere said. “This is what happens when we’re living this close to nature and we’re not managing it right.”

Other findings of the survey included:

- Two-thirds of those affected by the Palisades fire say they are uncertain they will have sufficient resources to fully cover rebuilding expenses and additional living costs that are not covered by insurance. In the Eaton fire area, 82% either do not have or are uncertain they will have sufficient resources.

- In the Palisades area, 70% of homeowners may not return if it takes more than three years to rebuild. In the Eaton fire area, 63% may not return after three years.

- A “look-alike” rebuild within 110% of their prior home size is planned by 77% of people who want to return to the Palisades fire area, while 84% plan a similar rebuild in the Eaton fire area.

- On average, homeowners in both areas expect about 70% of their rebuilding costs to be covered by insurance. On the low end of anticipated insurance support, 13% from the Palisades fire area and 19% from the Eaton fire area expect that between zero and 50% of their rebuilding costs will be covered by insurance.

- Owners estimate it will cost about $800 per square foot to rebuild in the Palisades fire area and $570 per square foot in the Eaton fire area.

- Cost is the top concern for owners in the Palisades fire area with a net worth of less than $5 million, and quality is the No. 1 concern for those with a net worth of less than $1 million in the Eaton fire area.

- More than 60% of homeowners in both areas are willing to forgo customization of their new homes if financial compromises are necessary.

Business

Delaying Medicare enrollment. What to know

Dear Liz: When my husband was approaching 65, he was employed and covered by a high-deductible healthcare plan with a health savings account by his employer. Neither his employer nor our local Social Security office had concrete advice on how to proceed about enrolling in Medicare, but after tremendous research, he eventually delayed enrollment. Now I am approaching 65. My husband is still working, and I am still covered by his health insurance, although both are in his name. Do I enroll in Medicare at the appropriate time or do I delay enrollment like he did?

Answer: Delaying Medicare enrollment can result in penalties that can increase your premiums for life. If you or a spouse is still working for an employer with 20 or more employees, however, generally you can opt to keep the employer-provided health insurance and delay applying for Medicare without being penalized. If you lose the coverage or employment ends, you’ll have eight months to sign up before being penalized.

Delaying your Medicare enrollment also allows your husband to continue making contributions on your behalf to his health savings account. In 2025, the HSA contribution limit is $4,300 for self-only coverage and $8,550 for family coverage, plus a $1,000 catch-up contribution for account holders 55 and older. Once you enroll in Medicare, HSA contributions are no longer allowed.

Medicare itself suggests reaching out to the employer’s benefits department to confirm you are appropriately covered and can delay your application. Let’s hope that by now your employer’s human resources department has gotten up to speed on this important topic.

Dear Liz: We read your recent column about capital gains and home sales. Our understanding is that if you sell and then buy a property of equal or greater value within the 180-day window, the basis for tax purposes is the purchase price, plus the $500,000 exemption, plus the improvements to the property, minus the depreciation, whatever that number comes to, and then the profit above that has to be reinvested or it is subject to capital gains. We talked to our CPA about this and he referred us to a site that specializes in 1031 exchanges.

Answer: You’ve mashed together two different sets of tax laws.

Only the sale of your primary residence will qualify for the home sale exemption, which for a married couple can exempt as much as $500,000 of home sale profits from taxation. You must have owned and lived in the home at least two of the previous five years.

Meanwhile, 1031 exchanges allow you to defer capital gains on investment property, such as commercial or rental real estate, as long as you purchase a similar property within 180 days (and follow a bunch of other rules). The replacement property doesn’t have to be more expensive, but if it’s less expensive or has a smaller mortgage than the property you sell, you could owe capital gains taxes on the difference.

It is possible to use both tax laws on the same property, but not simultaneously.

In the past, you could do a 1031 exchange and then convert the rental property into a primary residence to claim the home sale exemption after two years. Current tax law requires waiting at least five years after a 1031 exchange before a home sale exemption can be taken.

You can turn your primary residence into a rental and after two years do a 1031 exchange, but you would be deferring capital gains, while the home sale exemption allows you to avoid them on up to $500,000 of home sale profits.

Liz Weston, Certified Financial Planner, is a personal finance columnist. Questions may be sent to her at 3940 Laurel Canyon, No. 238, Studio City, CA 91604, or by using the “Contact” form at asklizweston.com.

Business

LinkedIn cuts 281 workers in California as tech layoffs continue

LinkedIn, the professional social network where people search for work, is shedding jobs.

The Microsoft-owned tech company has cut 281 workers in California, a notice filed this week to the California Employment Development Department shows.

Earlier this month, Microsoft said that it was terminating 3% of staff, or about 6,000 workers. The layoffs affected its California employees and LinkedIn workers.

LinkedIn is among major tech companies that have slashed their workforces this year. Meta, Google, Autodesk and other tech companies have also been cutting workers, citing various reasons, including restructuring, investments in artificial intelligence and low worker performance.

LinkedIn, headquartered in Sunnyvale and Mountain View, notified its employees about the layoffs on May 13. Workers posted about their pink slips on the social network, letting hiring managers and recruiters know that they were open to work.

The company didn’t respond to a request for comment. Its website says it has roughly 18,400 employees and offices in more than 30 cities globally.

LinkedIn’s California layoffs affected workers at its offices in San Francisco, Mountain View, Carpinteria and Sunnyvale. More than half of those cuts hit its workforce in Mountain View.

Software engineers were heavily impacted by LinkedIn’s California layoffs, according to data provided to the state. Talent account directors, senior product managers and other workers also lost their jobs.

The cuts come as tech companies are releasing more artificial intelligence-powered tools that can generate code. Executives have also said that would impact engineering jobs.

Microsoft Chief Executive Satya Nadella said in April that as much as 30% of the company’s code is written by AI. Nadella spoke during a conversation with Meta Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg at the social network’s AI developer conference.

As Microsoft competes to release more AI tools, the company has said that it’s trying to increase how fast it moves by reducing the number of managers and cutting down on redundancies.

It’s the latest cost-cutting round at LinkedIn. In 2023, the company laid off nearly 700 employees and said that it was trying to improve agility and accountability as part of a reorganization effort.

Microsoft purchased LinkedIn for $26 billion in 2016. In April, the company reported that its revenue in the third fiscal year quarter reached $4.3 billion in the third fiscal year quarter, up 7% over last year.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNeo-Nazi cult leader extradited to US for plot to kill Jewish children

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoDiscord might use AI to help you catch up on conversations

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie review: 'Dogma' re-release highlights thoughtful script – UPI.com

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoPlastic Spoons, Umbrellas, Violins: A Guide to What Americans Buy From China

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCade Cunningham Gains $45 Million From All-NBA Honors

-

Movie Reviews6 days ago

Movie Reviews6 days agoMOVIE REVIEW – Mission: Impossible 8 has Tom Cruise facing his final reckoning

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDefense secretary announces pay raises for Army paratroopers: 'We have you and your families in mind'

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Judge Blocks Trump Move to Ban Foreign Students at Harvard