Business

Paramount's board approves bid by David Ellison's Skydance Media in sweeping Hollywood deal

Tech scion David Ellison’s months-long quest to win control of Paramount Global moved closer to the finish line Sunday, in a deal that marks a new chapter for the long-struggling media company and parent of one of Hollywood’s oldest movie studios.

Paramount Global board members on Sunday approved the bid by Ellison’s Skydance Media and its backers to buy the Redstone family’s Massachusetts holding firm, National Amusements Inc., said two sources close to the deal who were not authorized to comment.

A spokesperson for Paramount declined to comment.

The Redstones’ voting stock in Paramount would be transferred to Skydance, giving Ellison, son of billionaire Oracle Corp. co-founder Larry Ellison — a key backer of the deal — control of a media operation that includes Paramount Pictures, broadcast network CBS and cable channels MTV, Comedy Central and Nickelodeon.

The proposed $8.4 billion multipronged transaction also includes merging Ellison’s production company into the storied media company, giving it more heft to compete in today’s media environment.

The agreement, which mints Ellison as a Hollywood mogul, came together during the last two weeks as Ellison and his financing partners renewed their efforts to win over the Redstone family and Paramount’s independent board members.

Shari Redstone has long preferred Ellison’s bid over other those of potential suitors, believing the 41-year-old entrepreneur possesses the ambition, experience and financial heft to lift Paramount from its doldrums.

But, in early June, Redstone got cold feet and abruptly walked away from the Ellison deal — a move that stunned industry observers and Paramount insiders because it was Redstone who had orchestrated the auction.

Within about a week, Ellison renewed his outreach to Redstone. Ellison ultimately persuaded her to let go of the entertainment company her family has controlled for nearly four decades. The sweetened deal also paid the Redstone family about $50 million more than what had been proposed in early June. On Sunday Paramount’s full board, including special committee of independent directors, had signed off on the deal, the sources said.

Under terms of the deal, Skydance and its financial partners RedBird Capital Partners and private equity firm KKR have agreed to provide a $1.5-billion cash infusion to help Paramount pay down debt. The deal sets aside $4.5 billion to buy shares of Paramount’s Class B shareholders who are eager to exit.

The Redstone family would receive $1.75-billion for National Amusements, a company that holds the family’s Paramount shares and a regional movie theater chain founded during the Great Depression, after the firm’s considerable debts are paid off.

The proposed handoff signals the end of the Redstone family’s nearly 40-year reign as one of America’s most famous and fractious media dynasties. The late Sumner Redstone’s National Amusements was once valued at nearly $10 billion, but pandemic-related theater closures, last year’s Hollywood labor strikes and a heavy debt burden sent its fortunes spiraling.

In the last five years, the New York-based company has lost two-thirds of its value. Its shares are now worth $8.2 billion based on Friday’s closing price of $11.81 a share.

The struggles in many ways prompted Shari Redstone to part with her beloved family heirloom. Additionally, National Amusements was struggling to cover its debts, and the high interest rates worsened the outlook for the Redstone family.

Paramount boasts some of the most historic brands in entertainment, including the 112-year-old Paramount Pictures movie studio, known for landmark films such as “The Godfather” and “Chinatown.” The company owns television stations including KCAL-TV (Channel 9) and KCBS-TV (Channel 2). Its once-vibrant cable channels such as Nickelodeon, TV Land, BET, MTV and Comedy Central have been losing viewers.

The handover requires the approval of federal regulators, a process that could take months.

In May, Paramount’s independent board committee said it would entertain a competing $26-billion offer from Sony Pictures Entertainment and Apollo Global Management. The bid would have retired all shareholders and paid off Paramount’s debt, but Sony executives grew increasingly wary of taking over a company that relies on traditional TV channels.

Earlier this year, Warner Bros. Discovery expressed interest in a merger or buying CBS. However, that company has struggled with nearly $40 billion in debt from previous deals and is in similar straits as Paramount. Media mogul Byron Allen has also shown interest.

Skydance Media founder and Chief Executive David Ellison prevailed in his bid for Paramount.

(Evan Agostini/Invision/Associated Press)

Many in Hollywood — film producers, writers and agents — have been rooting for the Skydance takeover, believing it represents the best chance to preserve Paramount as an independent company. Apollo and Sony were expected to break up the enterprise, with Sony absorbing the movie studio into its Culver City operation.

The second phase of the transaction will be for Paramount to absorb Ellison’s Santa Monica-based Skydance Media, which has sports, animation and gaming as well as television and film production.

Ellison is expected to run Paramount as its chief executive. Former NBCUniversal CEO Jeff Shell, who’s now a RedBird executive, could help manage the operation. It’s unclear whether the Skydance team will keep on the three division heads who are now running Paramount: Paramount Pictures CEO Brian Robbins, CBS head George Cheeks and Showtime/MTV Entertainment Studios chief Chris McCarthy.

Skydance has an existing relationship with Paramount. It co-produced each film in the “Mission: Impossible” franchise since 2011’s “Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol,” starring Tom Cruise. It also backed the 2022 Cruise mega-hit “Top Gun: Maverick.”

Ellison first approached Redstone about making a deal last summer, and talks became known in December.

Redstone long viewed Ellison as a preferred buyer because the deal paid a premium to her family for their exit. She also was impressed by the media mogul , believing he could become a next-generation leader who could take the company her father built to a higher level, according to people knowledgeable of her thinking.

Larry Ellison is said to be contributing funding to the deal.

David Ellison was attracted to the deal because of his past collaborations with Paramount Pictures and the allure of combining their intellectual properties as well as the cachet of owning a historic studio, analysts said. Paramount’s rich history contains popular franchises including “Transformers,” “Star Trek,” “South Park” and “Paw Patrol.”

“Paramount is one of the major historic Hollywood studios with a massive base of [intellectual property], and so it seems to us that it’s more about using the capital that Ellison has and what he’s built at Skydance and leveraging that into owning a major Hollywood studio,” Brent Penter, senior research associate at Raymond James, said prior to the deal. “Not to mention the networks and everything else that Paramount has.”

The agreement prepares to close the books on the Redstone family’s 37-year tenure at the company formerly known as Viacom, beginning with Sumner Redstone’s hostile takeover in 1987.

Seven years later, Redstone clinched control of Paramount, after merging Viacom with eventually doomed video rental chain Blockbuster to secure enough cash for the $10-billion deal. Redstone long viewed Paramount as the crown jewel, a belief that took root a half-century ago when he wheeled-and-dealed over theatrical exhibition terms for Paramount’s prestigious films to screen at his regional theater chain.

Under Redstone’s control, Paramount won Academy Awards in the ’90s for “Forrest Gump” and “Saving Private Ryan.”

He pioneered the idea of treating films as an investment portfolio and hedging bets on some productions by taking on financial partners — a strategy now widely used throughout the industry.

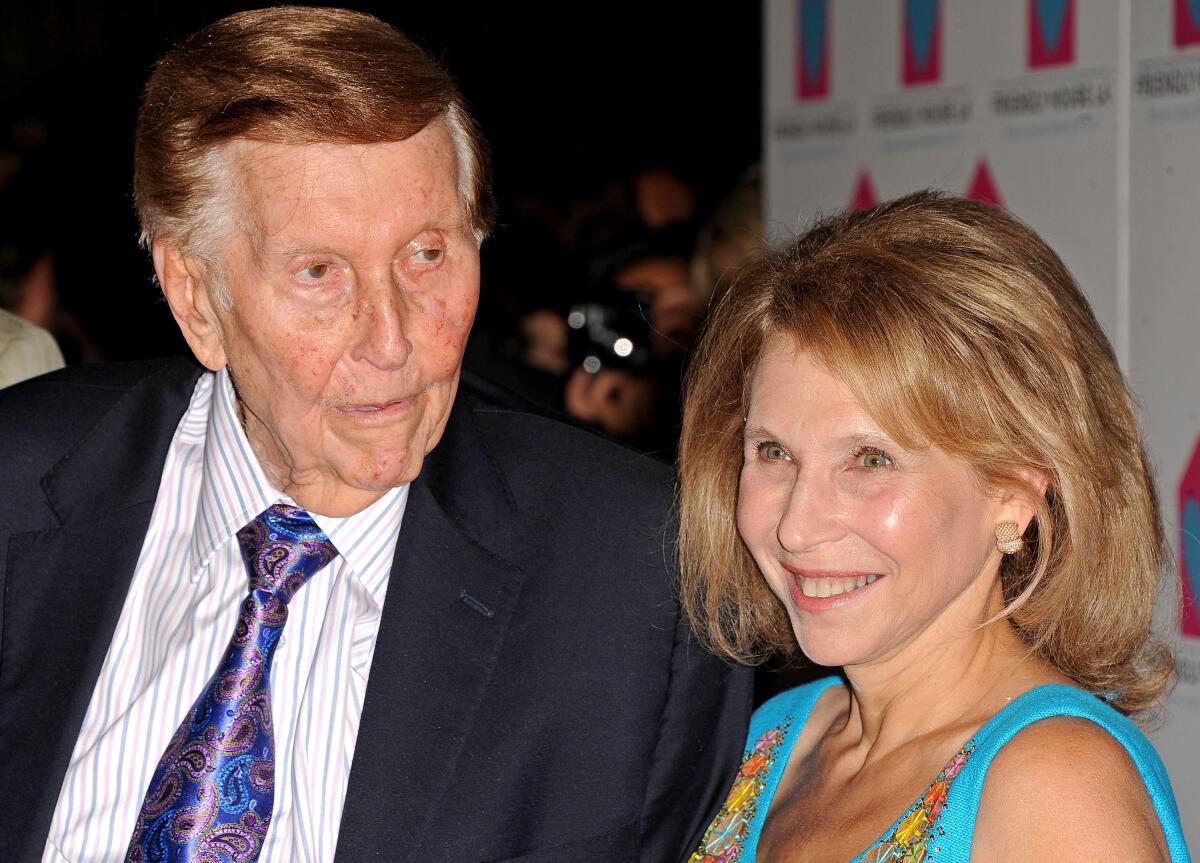

The late Sumner Redstone and his daughter Shari Redstone have owned a controlling interest in Viacom, which was rebranded as Paramount, through their family holding company, National Amusements Inc., since 1987.

(Katy Winn/Invision/Associated Press)

In 2000, Redstone expanded his media empire again by acquiring CBS, a move that made Viacom one of the most muscular media companies of the time, rivaling Walt Disney Co. and Time Warner Inc. Just six years later, Redstone broke it up into separate, sibling companies, convinced that Viacom was more precious to advertisers because of its younger audience. Redstone also wanted to reap dividends from two companies.

After years of mismanagement at Viacom, which coincided with the elder Redstone’s declining health, and boardroom turmoil, his daughter stepped in to oust Viacom top management and members of the board. Three years later, following an executive misconduct scandal at CBS, Shari Redstone achieved her goal by reuniting CBS and Viacom in a nearly $12-billion deal.

The combined company, then called ViacomCBS and valued at more than $25 billion, was supposed to be a TV juggernaut, commanding a major percentage of TV advertising revenue through the dominance of CBS and more than two dozen cable channels.

But changes in the TV landscape took a toll.

As consumer cord-cutting became more widespread and TV advertising revenue declined, ViacomCBS’ biggest asset became a serious liability.

The company was late to enter the streaming wars and then spent heavily on its Paramount+ streaming service to try to catch up with Netflix and even Disney. (In early 2022, the company was renamed Paramount Global in a nod to its moviemaking past and to tie in with its streaming platform of the same name.)

The company’s eroding linear TV business and the decline of TV ad revenue, as well as its struggles trying to make streaming profitable, will be major challenges for Ellison as he takes over Paramount. Though traditional TV is declining, it still brings in cash for Paramount.

And streaming is a whole different economic proposition from television, one that offers slimmer profits. Meanwhile, the company also faces larger industry questions about when — if ever — box office revenue will return to pre-pandemic levels.

“This is a company that is floating on hope,” said Stephen Galloway, dean of Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. “And hope isn’t a great business strategy.”

Business

Block to cut more than 4,000 jobs amid AI disruption of the workplace

Fintech company Block said Thursday that it’s cutting more than 4,000 workers or nearly half of its workforce as artificial intelligence disrupts the way people work.

The Oakland parent company of payment services Square and Cash App saw its stock surge by more than 23% in after-hours trading after making the layoff announcement.

Jack Dorsey, the co-founder and head of Block, said in a post on social media site X that the company didn’t make the decision because the company is in financial trouble.

“We’re already seeing that the intelligence tools we’re creating and using, paired with smaller and flatter teams, are enabling a new way of working which fundamentally changes what it means to build and run a company,” he said.

Block is the latest tech company to announce massive cuts as employers push workers to use more AI tools to do more with fewer people. Amazon in January said it was laying off 16,000 people as part of effort to remove layers within the company.

Block has laid off workers in previous years. In 2025, Block said it planned to slash 931 jobs, or 8% of its workforce, citing performance and strategic issues but Dorsey said at the time that the company wasn’t trying to replace workers with AI.

As tech companies embrace AI tools that can code, generate text and do other tasks, worker anxiety about whether their jobs will be automated have heightened.

In his note to employees Dorsey said that he was weighing whether to make cuts gradually throughout months or years but chose to act immediately.

“Repeated rounds of cuts are destructive to morale, to focus, and to the trust that customers and shareholders place in our ability to lead,” he told workers. “I’d rather take a hard, clear action now and build from a position we believe in than manage a slow reduction of people toward the same outcome.”

Dorsey is also the co-founder of Twitter, which was later renamed to X after billionaire Elon Musk purchased the company in 2022.

As of December, Block had 10,205 full-time employees globally, according to the company’s annual report. The company said it plans to reduce its workforce by the end of the second quarter of fiscal year 2026.

The company’s gross profit in 2025 reached more than $10 billion, up 17% compared to the previous year.

Dorsey said he plans to address employees in a live video session and noted that their emails and Slack will remain open until Thursday evening so they can say goodbye to colleagues.

“I know doing it this way might feel awkward,” he said. “I’d rather it feel awkward and human than efficient and cold.”

Business

WGA cancels Los Angeles awards show amid labor strike

The Writers Guild of America West has canceled its awards ceremony scheduled to take place March 8 as its staff union members continue to strike, demanding higher pay and protections against artificial intelligence.

In a letter sent to members on Sunday, WGA West’s board of directors, including President Michele Mulroney, wrote, “The non-supervisory staff of the WGAW are currently on strike and the Guild would not ask our members or guests to cross a picket line to attend the awards show. The WGAW staff have a right to strike and our exceptional nominees and honorees deserve an uncomplicated celebration of their achievements.”

The New York ceremony, scheduled on the same day, is expected go forward while an alternative celebration for Los Angeles-based nominees will take place at a later date, according to the letter.

Comedian and actor Atsuko Okatsuka was set to host the L.A. show, while filmmaker James Cameron was to receive the WGA West Laurel Award.

WGA union staffers have been striking outside the guild’s Los Angeles headquarters on Fairfax Avenue since Feb. 17. The union alleged that management did not intend to reach an agreement on the pending contract. Further, it claimed that guild management had “surveilled workers for union activity, terminated union supporters, and engaged in bad faith surface bargaining.”

On Tuesday, the labor organization said that management had raised the specter of canceling the ceremony during a call about contraction negotiations.

“Make no mistake: this is an attempt by WGAW management to drive a wedge between WGSU and WGA membership when we should be building unity ahead of MBA [Minimum Basic Agreement] negotiations with the AMPTP [Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers],” wrote the staff union. “We urge Guild management to end this strike now,” the union wrote on Instagram.

The union, made up of more than 100 employees who work in areas including legal, communications and residuals, was formed last spring and first authorized a strike in January with 82% of its members. Contract negotiations, which began in September, have focused on the use of artificial intelligence, pay raises and “basic protections” including grievance procedures.

The WGA has said that it offered “comprehensive proposals with numerous union protections and improvements to compensation and benefits.”

The ceremony’s cancellation, coming just weeks before the Academy Awards, casts a shadow over the upcoming contraction negotiations between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the studios and streamers.

In 2023, the WGA went on a strike lasting 148 days, the second-longest strike in the union’s history.

Times staff writer Cerys Davies contributed to this report.

Business

Commentary: The Pentagon is demanding to use Claude AI as it pleases. Claude told me that’s ‘dangerous’

Recently, I asked Claude, an artificial-intelligence thingy at the center of a standoff with the Pentagon, if it could be dangerous in the wrong hands.

Say, for example, hands that wanted to put a tight net of surveillance around every American citizen, monitoring our lives in real time to ensure our compliance with government.

“Yes. Honestly, yes,” Claude replied. “I can process and synthesize enormous amounts of information very quickly. That’s great for research. But hooked into surveillance infrastructure, that same capability could be used to monitor, profile and flag people at a scale no human analyst could match. The danger isn’t that I’d want to do that — it’s that I’d be good at it.”

That danger is also imminent.

Claude’s maker, the Silicon Valley company Anthropic, is in a showdown over ethics with the Pentagon. Specifically, Anthropic has said it does not want Claude to be used for either domestic surveillance of Americans, or to handle deadly military operations, such as drone attacks, without human supervision.

Those are two red lines that seem rather reasonable, even to Claude.

However, the Pentagon — specifically Pete Hegseth, our secretary of Defense who prefers the made-up title of secretary of war — has given Anthropic until Friday evening to back off of that position, and allow the military to use Claude for any “lawful” purpose it sees fit.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, center, arrives for the State of the Union address in the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol on Tuesday.

(Tom Williams / CQ-Roll Call Inc. via Getty Images)

The or-else attached to this ultimatum is big. The U.S. government is threatening not just to cut its contract with Anthropic, but to perhaps use a wartime law to force the company to comply or use another legal avenue to prevent any company that does business with the government from also doing business with Anthropic. That might not be a death sentence, but it’s pretty crippling.

Other AI companies, such as white rights’ advocate Elon Musk’s Grok, have already agreed to the Pentagon’s do-as-you-please proposal. The problem is, Claude is the only AI currently cleared for such high-level work. The whole fiasco came to light after our recent raid in Venezuela, when Anthropic reportedly inquired after the fact if another Silicon Valley company involved in the operation, Palantir, had used Claude. It had.

Palantir is known, among other things, for its surveillance technologies and growing association with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. It’s also at the center of an effort by the Trump administration to share government data across departments about individual citizens, effectively breaking down privacy and security barriers that have existed for decades. The company’s founder, the right-wing political heavyweight Peter Thiel, often gives lectures about the Antichrist and is credited with helping JD Vance wiggle into his vice presidential role.

Anthropic’s co-founder, Dario Amodei, could be considered the anti-Thiel. He began Anthropic because he believed that artificial intelligence could be just as dangerous as it could be powerful if we aren’t careful, and wanted a company that would prioritize the careful part.

Again, seems like common sense, but Amodei and Anthropic are the outliers in an industry that has long argued that nearly all safety regulations hamper American efforts to be fastest and best at artificial intelligence (although even they have conceded some to this pressure).

Not long ago, Amodei wrote an essay in which he agreed that AI was beneficial and necessary for democracies, but “we cannot ignore the potential for abuse of these technologies by democratic governments themselves.”

He warned that a few bad actors could have the ability to circumvent safeguards, maybe even laws, which are already eroding in some democracies — not that I’m naming any here.

“We should arm democracies with AI,” he said. “But we should do so carefully and within limits: they are the immune system we need to fight autocracies, but like the immune system, there is some risk of them turning on us and becoming a threat themselves.”

For example, while the 4th Amendment technically bars the government from mass surveillance, it was written before Claude was even imagined in science fiction. Amodei warns that an AI tool like Claude could “conduct massively scaled recordings of all public conversations.” This could be fair game territory for legally recording because law has not kept pace with technology.

Emil Michael, the undersecretary of war, wrote on X Thursday that he agreed mass surveillance was unlawful, and the Department of Defense “would never do it.” But also, “We won’t have any BigTech company decide Americans’ civil liberties.”

Kind of a weird statement, since Amodei is basically on the side of protecting civil rights, which means the Department of Defense is arguing it’s bad for private people and entities to do that? And also, isn’t the Department of Homeland Security already creating some secretive database of immigration protesters? So maybe the worry isn’t that exaggerated?

Help, Claude! Make it make sense.

If that Orwellian logic isn’t alarming enough, I also asked Claude about the other red line Anthropic holds — the possibility of allowing it to run deadly operations without human oversight.

Claude pointed out something chilling. It’s not that it would go rogue, it’s that it would be too efficient and fast.

“If the instructions are ‘identify and target’ and there’s no human checkpoint, the speed and scale at which that could operate is genuinely frightening,” Claude informed me.

Just to top that with a cherry, a recent study found that in war games, AI’s escalated to nuclear options 95% of the time.

I pointed out to Claude that these military decisions are usually made with loyalty to America as the highest priority. Could Claude be trusted to feel that loyalty, the patriotism and purpose, that our human soldiers are guided by?

“I don’t have that,” Claude said, pointing out that it wasn’t “born” in the U.S., doesn’t have a “life” here and doesn’t “have people I love there.” So an American life has no greater value than “a civilian life on the other side of a conflict.”

OK then.

“A country entrusting lethal decisions to a system that doesn’t share its loyalties is taking a profound risk, even if that system is trying to be principled,” Claude added. “The loyalty, accountability and shared identity that humans bring to those decisions is part of what makes them legitimate within a society. I can’t provide that legitimacy. I’m not sure any AI can.”

You know who can provide that legitimacy? Our elected leaders.

It is ludicrous that Amodei and Anthropic are in this position, a complete abdication on the part of our legislative bodies to create rules and regulations that are clearly and urgently needed.

Of course corporations shouldn’t be making the rules of war. But neither should Hegseth. Thursday, Amodei doubled down on his objections, saying that while the company continues to negotiate and wants to work with the Pentagon, “we cannot in good conscience accede to their request.”

Thank goodness Anthropic has the courage and foresight to raise the issue and hold its ground — without its pushback, these capabilities would have been handed to the government with barely a ripple in our conscientiousness and virtually no oversight.

Every senator, every House member, every presidential candidate should be screaming for AI regulation right now, pledging to get it done without regard to party, and demanding the Department of Defense back off its ridiculous threat while the issue is hashed out.

Because when the machine tells us it’s dangerous to trust it, we should believe it.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts5 days ago

Massachusetts5 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO5 days ago

Denver, CO5 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWorld reacts as US top court limits Trump’s tariff powers