Business

He claims to have saved California homeowners billions. The insurance industry hates him

Insurance industry groups have called it a “bomb-throwing bogus advocacy” group, a “publicity-seeking, dark money front,” and an organization out to protect its own “financial $elf-interest$.”

These are the kinds of attacks that Harvey Rosenfield and Consumer Watchdog, the advocacy group he founded nearly 40 years ago, have come to expect.

But in the last year, as home insurers have stopped writing new policies and retreated from parts of the state prone to wildfire, a new voice has joined the ranks of critics who say Harvey and Co. are making things worse: California’s elected insurance commissioner, Ricardo Lara, whose office has called Consumer Watchdog an entrenched interest group “defending its own piggy bank.”

California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara speaks at a state Capitol news conference in Sacramento.

(Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

If attacking a public advocacy group seems like an odd stance for an elected official, it’s made even odder by the fact that Lara wouldn’t have his job if it weren’t for Consumer Watchdog.

To understand the beef, you need to understand Proposition 103, a California law governing the insurance industry.

The campaign for that ballot measure in 1988 was one of the first missions of Consumer Watchdog, which formed in the wake of Ralph Nader’s success in spurring new consumer regulation.

That proposition, which Rosenfield helped write, enacted some of the most stringent insurance industry regulation in the nation. First, it created the office of an elected insurance commissioner to head the state Department of Insurance. Any time an insurance company seeks to raise prices, Proposition 103 requires that the firm apply to the commissioner for prior approval.

The goal, according to the text of the act, is to provide transparency into the insurance market and prevent insurers from charging “excessive, inadequate or unfairly discriminatory” rates to policyholders.

Nearly 35 years after Proposition 103 went into effect, Californians pay less for auto and home insurance than most Americans, with the state ranking among the bottom half of states for prices in both categories. But insurers say that long processing times for rate increases, among other regulations, have made it difficult to do business in the state as inflation and wildfire risks are on the rise.

One specific criticism of Consumer Watchdog revolves around a unique proviso of Proposition 103. The law allows public groups such as Consumer Watchdog to intervene in an insurance company’s application for a rate increase and argue — alongside the Department of Insurance — for what the ultimate price should be.

When groups such as Consumer Watchdog intervene, Proposition 103 stipulates that they can get paid for their efforts. After paying the intervening groups, insurance companies wind up passing those fees along to consumers. Insurance companies argue that this provides Consumer Watchdog and others a perverse incentive to turn every rate filing into a battle in order to get paid their fees.

“No other state has this kind of public participation and scrutiny built into the regulatory process, which is why Prop 103 is their number one target,” Rosenfield said. “It drives them nuts.”

“It comes down to the money, right?” said Carmen Balber, Consumer Watchdog’s executive director. “Thanks to the intervenor process, consumers pay less for their home and auto insurance than they would otherwise, and the industry has sought to claw back those profits for decades now.”

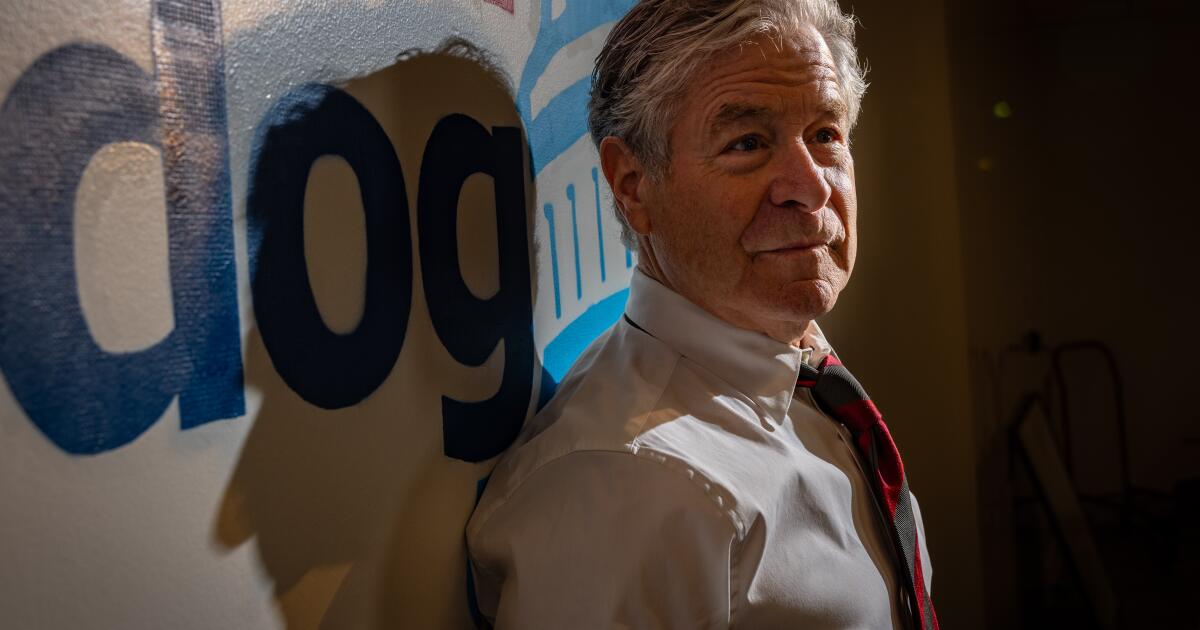

Consumer Watchdog’s Jamie Court, Harvey Rosenfield and Carmen Balber pose for a portrait in their Los Angeles offices Feb. 1.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

There has been friction between the insurance industry and consumer groups for decades, but things have recently started to boil over.

The American Property Casualty Insurance Assn., the nation’s largest insurance lobbying group, bankrolled a new website attacking Consumer Watchdog in late 2023. Spokespeople for the Insurance Information Institute and the Personal Insurance Federation of California regularly opine to reporters that Rosenfield, Balber and the group’s president, Jamie Court, are wrenches in the underwriting machinery.

“The industry is going after Consumer Watchdog harder than normal,” said Brian Sullivan, owner and editor of insurance industry publication Risk Information. And the feud between the group and the Department of Insurance keeps escalating. “I have never seen the relationship degrade to the point it’s at now,” Sullivan said.

The industry groups have been pushing for changes in Sacramento and at the Department of Insurance — and at the close of last year’s legislative session, saw some results in the forms of promises to loosen regulations.

Lara, the state’s insurance commissioner, has had a rocky relationship with Consumer Watchdog from the start. After he pledged to not accept campaign funds from insurers in his first run for the office in 2018, a San Diego Union-Tribune investigation revealed that Lara had accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from people and companies with ties to the insurance industry. Consumer Watchdog filed a public records request for communications between Lara’s department and the insurance companies linked to the donations, and then sued the commissioner for allegedly failing to respond to the request in full. The group lost its initial lawsuit, but is continuing to fight it in the state Courts of Appeal.

Since then, the group has accused Lara’s office of ramming through rate increases without adequate review or opportunity for public input, and called his plans to change regulations with the goal of bringing more insurers back to the state market a “sham.”

Lara, in turn, noted in a news conference announcing his proposed reforms that “bombastic statements from entrenched interest groups” help no one, and that “one entity can unreasonably prolong rate filings” while “materially benefiting from a process that is meant for broader public participation.”

Michael Soller, Lara’s spokesperson with the department, has been less coy about the “entity” in question. After Consumer Watchdog accused Lara of striking a secret deal with insurance companies in the fall, Soller put out a statement saying that the group’s “cynical claims hide the truth that [it] has earned millions of dollars signing off on rate increases — while denying the reality that insurance has become impossible for some Californians to find at any price.” He added that the group “is turning a blind eye to consumers’ needs while defending its own insurance piggy bank.”

Yes, they’re a big pain, but that’s their job.

— Rep. John Garamendi, describing Consumer Watchdog

While other consumer groups such as United Policyholders and the Consumer Federation of California have taken a more measured approach, Rosenfield has been blunt. “A commissioner more disposed to protect the industry has come along,” Rosenfield said. “Ultimately, there’s accountability for that within our system of democracy.”

“He’s kind of out a little bit on his own on this in terms of opposing what Lara’s doing,” said Brian Sullivan of Risk Information.

Increasingly, Consumer Watchdog is one of the only consumer advocates even participating in the Proposition 103 process. In the early days of the regime, half a dozen or so major consumer groups were willing to enter the fray. But over time, the pool of dedicated groups with the resources to fight long regulatory battles and only get paid months (and sometimes years) after their work begins, has dwindled to a handful. Now state records show that 75% of the time, if there’s an intervening entity in a rate filing, it’s Consumer Watchdog.

This is where the accusation of self-interest comes to bear. Since Rosenfield helped write Proposition 103, he also wrote in the fee mechanism that pays his salary at Consumer Watchdog. According to critics, that amounts to self-dealing at the consumers’ expense.

State records show that over the last two decades, the group has been paid $11.6 million in fees by the state for its interventions in rate filings, or an average of $575,000 each year. Proposition 103 isn’t Consumer Watchdog’s only policy focus, nor is it the group’s only source of revenue. Consumer Watchdog brought in $3.75 million in revenue in 2022 from donations, grants and other sources, according to public filings.

For that $11.6 million Proposition 103 payout, the group has been party to saving consumers $5.51 billion in the last two decades, according to an analysis produced by Consumer Watchdog. In the last five years, Consumer Watchdog says its actions have contributed to $2.1 billion in savings for Californians. The group arrived at these figures by comparing the dollar value of rate increases that insurance companies sought in the last 22 years against the final amount they got when Consumer Watchdog challenged their request.

In the last two years, when Consumer Watchdog intervened in a company’s request to raise its rates, the final result for ratepayers ended up 38% lower than what the companies requested for home insurance, and 29% lower for auto insurance, on average. When Consumer Watchdog didn’t enter the fray, the final amount approved by the state insurance department was only 2-3% lower than what companies requested on average, according to the report.

Soller, the insurance department spokesperson, calls these numbers “deeply flawed.”

“Based on our review, their claims are highly inflated,” Soller wrote in a statement. “They compared the amount originally requested by the insurance company to the amount approved, with no accounting for what the department’s role was in that three-party negotiation.”

In other words, it is impossible to attribute all of those savings to the group’s intervention because state insurance regulators probably would have argued down the companies’ requests on its own.

But the scale of California’s insurance market means even small concessions can have a big effect on ratepayers. If Consumer Watchdog’s interventions contributed 0.3% of those $5.2 billion that insurance rates have been pushed downward, then the group has saved Californians millions more than it’s been paid in fees.

Rep. John Garamendi (D-Walnut Grove), who served as the state’s first and fourth elected insurance commissioner, finds the attempts to discredit Consumer Watchdog disturbing, if not surprising.

Rep. John Garamendi speaks at a meeting in South Lake Tahoe, Calif., in August 2019.

(Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

“Yes, they’re a big pain, but that’s their job,” Garamendi said. “These organizations are absolutely essential in the process of a rational insurance market, with premiums that are fairly priced, policies that are clearly understood and written, claims that are paid.”

Sullivan, for his part, believes that the hate focused on Harvey and Consumer Watchdog is more of a sideshow than a debate about how to respond to the changing insurance market.

“It has nothing to do with the problems in the state,” Sullivan said. “They’re fighting amongst themselves over very little — it isn’t the intervenor process causing the long delay times” that are at the root of the industry’s problems with the regulatory system.

The fundamental problem, according to industry groups and observers, is that rate filings often take a year or more to work their way through the system, which can lead to a punishing lag between costs and revenues for insurers.

Many insurers are still limiting the number of new policies they write in California. If changes do come, it would take many months, and probably years, before they could ripple through to policies and change insurers’ business decisions about operating in the state.

Commissioner Lara is hiring more staff and changing filing rules with the goal of speeding up the process. His office also plans to roll out new rules that could allow insurance companies to lock in higher prices further in advance, by allowing them to use algorithmic modeling to set higher prices for wildfire risk zones and pass through some of the costs of reinsurance — insurance policies that insurance companies themselves buy to cover their own losses.

Consumer Watchdog, in a surprise to no one, has some strong opinions about Lara’s plans.

Business

Startup Varda Space Industries snags former Mattel plant in El Segundo

In an expansion of its business of processing pharmaceuticals in Earth’s orbit, Varda Space Industries is renting a large El Segundo plant where toy manufacturer Mattel used to design Hot Wheels and Barbie dolls.

The plant in El Segundo’s aerospace corridor will be an extension of Varda Space Industries’ headquarters in a much smaller building on nearby Aviation Boulevard.

Varda will occupy a 205,443-square-foot industrial and office campus at 2031 E. Mariposa Ave., which will give it additional capacity to manufacture spacecraft at scale, the company said.

Originally built in the 1940s as an aircraft facility, the complex has a history as part of aerospace and defense industries that have long shaped the South Bay and is near a host of major defense and space contractors. It is also close to Los Angeles Air Force Base, headquarters to the Space Systems Command.

Workers test AstroForge’s Odin asteroid probe, which was lost in space after launch this year.

(Varda Space Industries)

Varda is one of a new generation of aerospace startups that have flourished in Southern California and the South Bay over the last several years, particularly in El Segundo, often with ties to SpaceX.

Elon Musk’s company, founded in 2002 in El Segundo, has revolutionized the industry with reusable rockets that have radically lowered the cost of lifting payloads into space. Though it has moved its headquarters to Texas, SpaceX retains large-scale operations in Hawthorne.

Varda co-founder and Chief Executive Will Bruey is a former SpaceX avionics engineer, and the company’s spacecraft are launched on SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9 rockets from Vandenberg Space Force Base in Santa Barbara County.

Varda makes automated labs that look like cylindrical desktop speakers, which it sends into orbit in capsules and satellite platforms it also builds. There, in microgravity, the miniature labs grow molecular crystals that are purer than those produced in Earth’s gravity for use in pharmaceuticals.

It has contracts with drug companies and also the military, which tests technology at hypersonic speeds as the capsules return to Earth.

Its fifth capsule was launched in November and returned to Earth in late January; its next mission is set in the coming weeks. Varda has more than 10 missions scheduled on Falcon 9s through 2028.

For the last several decades, the Mariposa Avenue property served as the research and development center for Mattel Toys. El Segundo has also long been a center for the toy industry as companies like to set up shop in the shadow of Mattel.

The Mattel facility “has always been an exceptional property with a legacy tied to aerospace innovation, and leasing to Varda Space Industries feels like a natural continuation of that story,” said Michael Woods, a partner at GPI Cos., which owns the property.

“We are proud to support a company that is genuinely pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, and are excited to watch Varda grow and thrive here in El Segundo,” Woods said.

As one of the country’s most active hubs of aerospace and defense innovation, El Segundo has seen its industrial property vacancy fall to 3.4% on demand from space companies, government contractors and technology startups, real estate brokerage CBRE said.

Successful startups often have to leave the neighborhood when they want to expand, real estate broker Bob Haley of CBRE said. The 9-acre Mattel facility was big enough to keep Varda in the city.

Last year, Varda subleased about 55,000 square feet of lab space from alternative protein company Beyond Meat at 888 Douglas St. in El Segundo, which it started moving into in June.

Varda will get the keys to its new building in December and spend four to eight months building production and assembly facilities as it ramps up operations. By the end of next year, it expects to have constructed 10 more spacecraft.

In the future, Varda could consolidate offices there, given its size. Currently, though, the plan is to retain all properties, creating a campus of three buildings within a mile of one another that are served by the company’s transportation services, Chief Operating Officer Jonathan Barr said.

“We already have Varda-branded shuttles running up and down Aviation Boulevard,” he said.

Business

How Iran War Is Threatening Global Oil and Gas Supplies

Ships near the Strait of Hormuz before and after attacks began

Every day, around 80 oil and gas tankers typically pass through the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow waterway off Iran’s southern coast that carries a fifth of the world’s oil and a significant amount of natural gas.

On Monday, just two oil and gas tankers appear to have crossed the strait, according to a New York Times analysis of shipping activity from Kpler, an industry data firm. Since then, one tanker passed through.

“It’s a de facto closure,” said Dan Pickering, chief investment officer of Pickering Energy Partners, a Houston financial services firm. “You’ve got a significant number of vessels on either side of the strait but no one is willing to go through.”

Tankers have been staying away from Hormuz since the U.S.-Israeli attacks on Iran that began on Saturday. A prolonged conflict could ripple broadly across the global economy, threatening the energy supplies of countries halfway around the world and stoking inflation.

International oil prices have climbed 12 percent since the fighting began, trading Tuesday around $81 a barrel, and natural gas prices have surged in Europe and in Asia.

A senior Iranian military official threatened on Monday to “set on fire” any ships traveling through the Strait of Hormuz. Vessels in the region have already come under attack. Several oil and gas facilities have also been struck or affected by nearby shelling, though the damage did not initially appear to be catastrophic.

Where ships and energy facilities have been damaged

A fire broke out Tuesday at a major energy hub in Fujairah, United Arab Emirates, from the falling debris of a downed drone, the authorities said. On Monday, Qatar halted production of liquefied natural gas, or fuel that has been cooled so that it can be transported on ships, after attacks on its facilities.

The sharp reduction in tanker traffic is reducing the supply of oil and gas to world markets, pushing up prices for both commodities. And the longer that ships stay away from the Strait of Hormuz, the less oil and gas get out to the world, which could raise prices even more.

Shipping companies have paused their tankers to protect their crew and cargo, and because insurance companies are charging significantly more to cover vessels in the conflict area.

On Tuesday, President Trump said that “if necessary,” the U.S. Navy would begin escorting tankers through the strait. He also said a U.S. government agency would begin offering “political risk insurance” to shipping lines in the area.

In addition to tankers, other large vessels regularly go through the strait, including car carriers and container ships. In normal conditions, nearly 160 make the trip each day.

Some ships in the region turn off the devices that broadcast their positions, while others transmit false locations — making it hard to give a full picture of the traffic in the strait.

The Shiva is a small oil tanker that has repeatedly faked its location, according to TankerTrackers.com, which tracks global oil shipments. It is suspected of carrying sanctioned Iranian oil, according to Kpler. The Shiva was one of the two tankers that crossed the strait on Monday.

The oil and gas that typically move through the strait come from big producing countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran and United Arab Emirates, and are exported around the world.

Where tankers moving through the Strait have traveled

In 2024, more than 80 percent of the oil and gas transported through the Strait of Hormuz went to Asia. China, India, Japan and South Korea were the top importers, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Countries have energy stockpiles that could last them into the coming months, but a continued shutdown of the strait could damage their economies.

Several big disruptions have roiled supply chains in recent years, but the tanker standstill in the Strait of Hormuz could have an outsize impact.

Business

Paramount credit downgraded to ‘junk’ status over debt worries

Paramount Skydance’s jubilation over its come-from-behind victory to claim Warner Bros. Discovery has entered a new phase:

Call it the deal-debt hangover.

Two major ratings agencies have raised concerns about Paramount’s credit because of the enormous debt the David Ellison-led company will have to shoulder — at least $79 billion — once it absorbs the larger Warner Bros. Discovery, bringing CNN, HBO, TBS and Cartoon Network into the Paramount fold.

Fitch Ratings said Monday that it placed Paramount on its “negative” ratings watch, and downgraded its credit to BB+ from BBB-, which puts the company’s credit into “junk” territory. Fitch said it took action due to “uncertainty” surrounding Paramount’s $110-billion deal for Warner Bros. Discovery, which the boards of both companies approved on Friday.

S&P Global Ratings took similar action.

To finance the Warner takeover, Ellison’s billionaire father, Larry Ellison, has agreed to guarantee the $45.7 billion in equity needed. Bank of America, Citibank and Apollo Global have agreed to provide Paramount with more than $54 billion in debt financing.

“Potential credit risks include the prospective debt-funded structure, Fitch’s expectation of materially elevated leverage and limited visibility on post-transaction financial policy and capital structure,” Fitch said.

Late last week, Paramount sent $2.8 billion to Netflix as a “termination fee” to officially end the streaming giant’s pursuit of Warner Bros. That payment paved the way for Warner and Paramount’s board to enter into the new merger agreement.

Paramount hopes the merger will be wrapped up by the end of September. It needs the approval of Warner Bros. Discovery shareholders and regulators, including the European Union.

Paramount executives acknowledged this week the new company would emerge with $79 billion in debt — a considerably higher total than what Warner Bros. Discovery had following its spinoff from AT&T. That 2022 transaction left Warner Bros. Discovery with nearly $55 billion of debt, a burden that led to endless waves of cost-cutting, including thousands of layoffs and dozens of canceled projects.

Warner still has $33.5 billion in debt, a lingering legacy that will be passed on to Paramount.

Paramount plans to restructure about $15 billion in Warner Bros. Discovery’s existing debt.

Paramount CEO David Ellison at a 2024 movie premiere for a Netflix show.

(Evan Agostini / Invision / AP)

Paramount told Wall Street it would find more than $6 billion in cost cuts or “synergies” within three years — a number that has weighed heavily on entertainment industry workers, particularly in Los Angeles.

Hollywood already is reeling from previous mergers in addition to a sharp pullback in film and television production locally as filmmakers chase tax credits offered overseas and in other states, including New York and New Jersey.

Some entertainment executives, including Netflix Co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos, have speculated that Paramount will need to find more than $10 billion in cost cuts to make the math work. More recently, Sarandos went higher, telling Bloomberg News that Paramount may need $16 billion in cuts.

Cognizant of widespread fears about additional layoffs, Paramount Chief Operating Officer Andrew Gordon took steps this week to try to tamp down such concerns.

Gordon is a former Goldman Sachs banker and a former executive with RedBird Capital Partners, an investor in Paramount and the proposed Warner Bros. deal. He joined Paramount last August as part of the Ellison takeover.

During a conference call Monday with analysts, Gordon said Paramount would look beyond the workforce for cuts because the company wants to maintain its film and TV production levels.

Paramount plans to look for cost savings by consolidating the “technology stacks and cloud providers” for its streaming services, including Paramount+ and HBO Max, Gordon said. The company also would search for reductions in corporate overhead, marketing expenses, procurement, business services and “optimizing the combined real estate footprint.”

It’s unclear whether Paramount would sell the historic Melrose Avenue lot or simply centralize the sprawling operations onto the Warner Bros. and Paramount lots in Burbank and Hollywood.

Workers are scattered throughout the region.

HBO, owned by Warner Bros. Discovery, maintains its West Coast headquarters in Culver City; CBS television stations operate from CBS’ former lot off Radford Avenue in Studio City; and CBS Entertainment and Paramount cable channels executive teams are located in a high-rise off Gower Street and Sunset Boulevard, blocks from the Paramount movie studio lot.

“The combination of PSKY and WBD could create a materially stronger business than either individual entity,” Standard & Poor’s said in its note to investors. “However, this transaction presents unique challenges because it would involve the combination of three companies, with the smallest, Skydance, being the controlling entity.”

David Ellison’s production firm, Skydance Media, was the entity that bought Paramount, creating Paramount Skydance.

Ellison has not announced what the combined company will be called.

Paramount shares closed down more than 6% Tuesday to $12.45.

Warner Bros. Discovery fell 1% to $28.20. Netflix added less than 1% to close at $97.70.

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO7 days ago

Denver, CO7 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Oregon5 days ago

Oregon5 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling