Science

A mysterious, highly active undersea volcano near California could erupt later this year. What scientists expect

• Axial Seamount is the best-monitored submarine volcano in the world.

• It’s the most active undersea volcano closest to California.

• It could erupt by the end of the year.

A mysterious and highly active undersea volcano off the Pacific Coast could erupt by the end of this year, scientists say.

Nearly a mile deep and about 700 miles northwest of San Francisco, the volcano known as Axial Seamount is drawing increasing scrutiny from scientists who only discovered its existence in the 1980s.

Located in a darkened part of the northeast Pacific Ocean, the submarine volcano has erupted three times since its discovery — in 1998, 2011 and 2015 — according to Bill Chadwick, a research associate at Oregon State University and an expert on the volcano.

Fortunately for residents of California, Oregon and Washington, Axial Seamount doesn’t erupt explosively, so it poses zero risk of any tsunami.

“Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Rainier, Mt. Hood, Crater Lake — those kind of volcanoes have a lot more gas and are more explosive in general. The magma is more viscous,” Chadwick said. “Axial is more like the volcanoes in Hawaii and Iceland … less gas, the lava is very fluid, so the gas can get out without exploding.”

The destructive force of explosive eruptions is legendary: when Mt. Vesuvius blew in 79 AD, it wiped out the ancient Roman city of Pompeii; when Mt. St. Helens erupted in 1980, 57 people died; and when the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai volcano in Tonga’s archipelago exploded in 2022 — a once-in-a-century event — the resulting tsunami, which reached a maximum height of 72 feet, caused damage across the Pacific Ocean and left at least six dead.

Axial Seamount, by contrast, is a volcano that, during eruptions, oozes lava — similar to the type of eruptions in Kilauea on the Big Island of Hawaii. As a result, Axial’s eruptions are not noticeable to people on land.

It’s a very different story underwater.

Heat plumes from the eruption will rise from the seafloor — perhaps half a mile — but won’t reach the surface, said William Wilcock, professor of oceanography at the University of Washington.

Jason is a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) system designed to allow scientists to have access to the seafloor without leaving the ship.

(Dave Caress/MBARI)

The outermost layer of the lava flow will almost immediately cool and form a crust, but the interior of the lava flow can remain molten for a time, Chadwick said. “In some places … the lava comes out slower and piles up, and then there’s all this heat that takes a long time to dissipate. And on those thick flows, microbial mats can grow, and it almost looks like snow over a landscape.”

Sea life can die if buried by the lava, which also risks destroying or damaging scientific equipment installed around the volcano to detect eruptions and earthquakes. But the eruption probably won’t affect sea life such as whales, which are “too close to the surface” to be bothered by the eruption, Wilcock said.

Also, eruptions at Axial Seamount aren’t expected to trigger a long-feared magnitude 9.0 earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone. Such an earthquake would probably spawn a catastrophic tsunami for Washington, Oregon and California’s northernmost coastal counties. That’s because Axial Seamount is located too far away from that major fault.

Axial Seamount is one of countless volcanoes that are underwater. Scientists estimate that 80% of Earth’s volcanic output — magma and lava — occurs in the ocean.

Axial Seamount has drawn intense interest from scientists. It is now the best-monitored underwater volcano in the world.

The volcano is a prolific erupter in part because of its location, Chadwick said. Not only is it perched on a ridge where the Juan de Fuca and Pacific tectonic plates spread apart from each other — creating new seafloor in the process — but the volcano is also planted firmly above a geological “hot spot” — a region where plumes of superheated magma rise toward the Earth’s surface.

For Chadwick and other researchers, frequent eruptions offer the tantalizing opportunity to predict volcanic eruptions weeks to months in advance — something that’s very difficult to do with other volcanoes. (There’s also much less likelihood anyone will get mad if scientists get it wrong.)

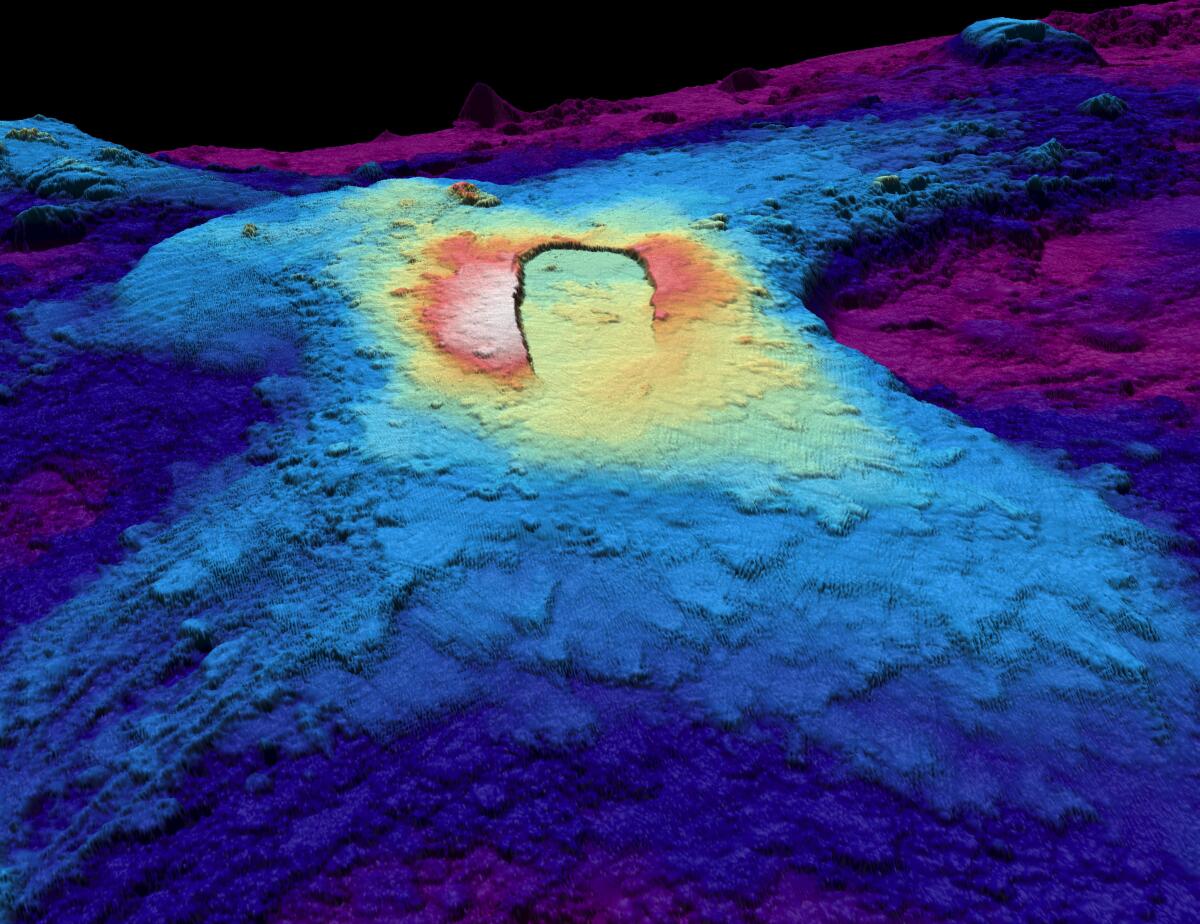

A three-dimensional topographic depiction showing the summit caldera of Axial Seamount, a highly active undersea volcano off the Pacific Coast. Warmer colors indicate shallower surfaces; cooler colors indicate deeper surfaces.

(Susan Merle / Oregon State University)

“For a lot of volcanoes around the world, they sit around and are dormant for long periods of time, and then suddenly they get active. But this one is pretty active all the time, at least in the time period we’ve been studying it,” Chadwick said. “If it’s not erupting, it’s getting ready for the next one.”

Scientists know this because they’ve spotted a pattern.

“Between eruptions, the volcano slowly inflates — which means the seafloor rises. … And then during an eruption, it will, when the magma comes out, the volcano deflates and the seafloor drops down,” Wilcock said.

Eruptions, Chadwick said, are “like letting some air out of the balloon. And what we’ve seen is that it has inflated to a similar level each time when an eruption is triggered,” he said.

Chadwick and fellow scientist Scott Nooner predicted the volcano’s 2015 eruption seven months before it happened after they realized the seafloor was inflating quite quickly and linearly. That “made it easier to extrapolate into the future to get up to this threshold that it had reached before” eruption, Chadwick said.

But making predictions since then has been more challenging. Chadwick started making forecast windows in 2019, but around that time, the rate of inflation started slowing down, and by the summer of 2023, “it had almost stopped. So then it was like, ‘Who knows when it’s going to erupt?’”

A deep-sea octopus explores the lava flows four months after the Axial Seamount volcano erupted in 2015.

(Bill Chadwick, Oregon State University / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution / National Science Foundation)

But in late 2023, the seafloor slowly began inflating again. Since the start of 2024, “it’s been kind of cranking along at a pretty steady rate,” he said. He and Nooner, of the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, made the latest eruption prediction in July 2024 and posted it to their blog. Their forecast remains unchanged.

“At the rate of inflation it’s going, I expect it to erupt by the end of the year,” Chadwick said.

But based on seismic data, it’s not likely the volcano is about to erupt imminently. While scientists haven’t mastered predicting volcanic eruptions weeks or months ahead of time, they do a decent job of forecasting eruptions minutes to hours to days ahead of time, using clues like an increased frequency of earthquakes.

At this point, “we’re not at the high rate of seismicity that we saw before 2015,” Chadwick said. “It wouldn’t shock me if it erupted tomorrow, but I’m thinking that it’s not going to be anytime soon on the whole.”

He cautioned that his forecast still amounts to an experiment, albeit one that has become quite public. “I feel like it’s more honest that way, instead of doing it in retrospect,” Chadwick said in a presentation in November. The forecast started to garner attention after he gave a talk at the American Geophysical Union meeting in December.

On the bright side, he said, “there’s no problem of having a false alarm or being wrong,” because the predictions won’t affect people on land.

If the predictions are correct, “maybe there’s lessons that can be applied to other more hazardous volcanoes around the world,” Chadwick said. As it stands now, though, making forecasts for eruptions for many volcanoes on land “are just more complicated,” without having a “repeatable pattern like we’re seeing at this one offshore.”

Scientists elsewhere have looked at other ways to forecast undersea eruptions. Scientists began noticing a repeatable pattern in the rising temperature of hydrothermal vents at a volcano in the East Pacific and the timing of three eruptions in the same spot over the last three decades. “And it sort of worked,” Chadwick said.

Plenty of luck allowed scientists to photograph the eruption of the volcanic site known as “9 degrees 50 minutes North on the East Pacific Rise,” which was just the third time scientists had ever captured images of active undersea volcanism.

But Chadwick doubts researchers will be fortunate enough to videotape Axial Seamount’s eruption.

Although scientists will be alerted to it by the National Science Foundation-funded Ocean Observatories Initiative Regional Cabled Array — a sensor system operated by the University of Washington — getting there in time will be a challenge.

“You have to be in the right place at the right time to catch an eruption in action, because they don’t last very long. The ones at Axial probably last a week or a month,” Chadwick said.

And then there’s the difficulty of getting a ship and a remotely operated vehicle or submarine to capture the images. Such vessels are generally scheduled far in advance, perhaps a year or a year and a half out, and projects are tightly scheduled.

Chadwick last went to the volcano in 2024 and is expected to go out next in the summer of 2026. If his predictions are correct, Axial Seamount will have already erupted.

Science

Department of Education finds San Jose State violated Title IX regarding transgender volleyball player

The U.S. Department of Education has given San José State 10 days to comply with a list of demands after finding that the university violated Title IX concerning a transgender volleyball player in 2024.

A federal investigation was launched into San José State a year ago after controversy over a transgender player marred the 2024 volleyball season. Four Mountain West Conference teams — Boise State, Wyoming, Utah State and Nevada-Reno — each chose to forfeit or cancel two conference matches to San José State. Boise State also forfeited its conference tournament semifinal match to the Spartans.

The transgender player, Blaire Fleming, was on the San José State roster for three seasons after transferring from Coastal Carolina, although opponents protested the player’s participation only in 2024.

In a news release Wednesday, the Education Department warned that San José State risks “imminent enforcement action” if it doesn’t voluntarily resolve the violations by taking the following actions, not all of which pertain solely to sports:

1) Issue a public statement that SJSU will adopt biology-based definitions of the words “male” and “female” and acknowledge that the sex of a human — male or female — is unchangeable.

2) Specify that SJSU will follow Title IX by separating sports and intimate facilities based on biological sex.

3) State that SJSU will not delegate its obligation to comply with Title IX to any external association or entity and will not contract with any entity that discriminates on the basis of sex.

4) Restore to female athletes all individual athletic records and titles misappropriated by male athletes competing in women’s categories, and issue a personalized letter of apology on behalf of SJSU to each female athlete for allowing her participation in athletics to be marred by sex discrimination.

5) Send a personalized apology to every woman who played in SJSU’s women’s indoor volleyball from 2022 to 2024, beach volleyball in 2023, and to any woman on a team that forfeited rather than compete against SJSU while a male student was on the roster — expressing sincere regret for placing female athletes in that position.

“SJSU caused significant harm to female athletes by allowing a male to compete on the women’s volleyball team — creating unfairness in competition, compromising safety, and denying women equal opportunities in athletics, including scholarships and playing time,” Kimberly Richey, Education Department assistant secretary for civil rights, said.

“Even worse, when female athletes spoke out, SJSU retaliated — ignoring sex-discrimination claims while subjecting one female SJSU athlete to a Title IX complaint for allegedly ‘misgendering’ the male athlete competing on a women’s team. This is unacceptable.”

San José State responded with a statement acknowledging that the Education Department had informed the university of its investigation and findings.

“The University is in the process of reviewing the Department’s findings and proposed resolution agreement,” the statement said. “We remain committed to providing a safe, respectful, and inclusive educational environment for all students while complying with applicable laws and regulations.”

In a New York Times profile, Fleming said she learned about transgender identity when she was in eighth grade. “It was a lightbulb moment,” she said. “I felt this huge relief and a weight off my shoulders. It made so much sense.”

With the support of her mother and stepfather, Fleming worked with a therapist and a doctor and started to socially and medically transition, according to the Times. When she joined the high school girls’ volleyball team, her coaches and teammates knew she was transgender and accepted her.

Fleming’s first two years at San José State were uneventful, but in 2024 co-captain Brooke Slusser joined lawsuits against the NCAA, the Mountain West Conference and representatives of San José State after alleging she shared hotel rooms and locker rooms with Fleming without being told she is transgender.

The Education Department also determined that Fleming and a Colorado State player conspired to spike Slusser in the face, although a Mountain West investigation found “insufficient evidence to corroborate the allegations of misconduct.” Slusser was not spiked in the face during the match.

President Trump signed an executive order a year ago designed to ban transgender athletes from competing on girls’ and women’s sports teams. The order stated that educational institutions and athletic associations may not ignore “fundamental biological truths between the two sexes.” The NCAA responded by banning transgender athletes.

The order, titled “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports,” gives federal agencies, including the Justice and Education departments, wide latitude to ensure entities that receive federal funding abide by Title IX in alignment with the Trump administration’s view, which interprets a person’s sex as the gender they were assigned at birth.

San José State has been in the federal government’s crosshairs ever since. If the university does not comply voluntarily to the actions listed by the government, it could face a Justice Department lawsuit and risk losing federal funding.

“We will not relent until SJSU is held to account for these abuses and commits to upholding Title IX to protect future athletes from the same indignities,” Richey said.

San José State was found in violation of Title IX in an unrelated case in 2021 and paid $1.6 million to more than a dozen female athletes after the Department of Justice found that the university failed to properly handle the students’ allegations of sexual abuse by a former athletic trainer.

The federal investigation found that San José State did not take adequate action in response to the athletes’ reports and retaliated against two employees who raised repeated concerns about Scott Shaw, the former director of sports medicine. Shaw was sentenced to 24 months in prison for unlawfully touching female student-athletes under the guise of providing medical treatment.

The current findings against San José State came two weeks after federal investigators announced that the California Community College Athletic Assn. and four other state colleges and school districts are the targets of a probe over whether their transgender participation policies violate Title IX.

The investigation targets a California Community College Athletic Assn. rule that allows transgender and nonbinary students to participate on women’s sports teams if the students have completed “at least one calendar year of testosterone suppression.”

Also, the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights has launched 18 Title IX investigations into school districts across the United States on the heels of the Supreme Court hearing oral arguments on efforts to protect women’s and girls’ sports.

Science

The share of Americans medically obese is projected to rise to almost 50% by 2035

On Wednesday, a new study published in JAMA by researchers at the University of Washington in Seattle projected that by 2035, nearly half of all American adults, about 126 million individuals, will be living with obesity. The study draws on data from more than 11 million participants via the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and from the independent Gallup Daily Survey.

The projections show a striking increase in the prevalence of obesity over the past few decades in the U.S. In 1990, only 19.3% of U.S. adults were obese, according to the study. That figure more than doubled to 42.5% by 2022, and is forecast to reach 46.9% by 2035.

The study highlights significant disparities across states, ages, and racial and ethnic groups. While every state is expected to see increases, the sharpest rises are projected for Midwestern and Southern states.

For example, nationwide, by 2035, the study projects that 60% (11.5 million adults) of Black women and 54% (14.5 million) of Latino women will suffer from obesity when compared with 47% (36.5 million) of white women. Similarly, 48% (13.2 million) of Latino men will suffer from the disease compared with 45% (34.4 million) of white men and 43% (7.61 million) of Black men.

The findings say California will see similar trends in gender and racial disparities. The study projects that by 2035, obesity rates among Latino and Black women in California will reach nearly 60%, compared with nearly 40% for their white counterparts. Additionally, Latino men in California could see rates over 50%, compared with nearly 40% for their white counterparts.

“These numbers are not surprising, given the systemic inequalities that exist,” in many California cities, said Dr. Amanda Velazquez, director of obesity medicine at Cedars-Sinai Hospital, pointing to economic instability, chronic stress and the car-dependency of Los Angeles and other California metro areas. “There are challenges for access to nutritious foods, depending on where you’re at in the city,” Velazquez said. ”There’s also disparities in the access to healthcare, especially to treatment for obesity.”

That’s recently become more of a challenge, since changes in Medi-Cal plans that went into effect at the beginning of this year mean obesity medication and treatment are no longer covered for hundreds of thousands of low-income Californians. “To take that away is devastating,” said Velazquez.

Despite these disparities, California is projected to fare better than most other states, with its rates of obesity growing more slowly than the national average.

“There are statewide and local policies that influence food, nutrition and social determinants of health for individuals,” said Velazquez.

Church pointed to measures such as SB 12 and SB 677, passed in the mid 2000s, which set strict nutritional standards for schools, existing menu labeling laws at both the state and federal levels requiring restaurants to provide nutritional facts on menu items, and cities like Berkeley and Oakland imposing local soda taxes as key local and statewide initiatives to keep obesity at bay.

To keep up this momentum, both doctors stressed that California must continue to strengthen school nutrition standards, expand transportation infrastructure that encourages walking instead of driving, maintain and expand economic disincentives to unhealthy foods, such as beverage taxes, and address food deserts by incentivizing new grocery stores and farmers’ markets in underserved neighborhoods.

Future efforts, Church says, should prioritize the Black and Latino populations identified by the study as most affected.

Science

Pediatricians urge Americans to stick with previous vaccine schedule despite CDC’s changes

For decades, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spoke with a single voice when advising the nation’s families on when to vaccinate their children.

Since 1995, the two organizations worked together to publish a single vaccine schedule for parents and healthcare providers that clearly laid out which vaccines children should get and exactly when they should get them.

Today, that united front has fractured. This month, the Department of Health and Human Services announced drastic changes to the CDC’s vaccine schedule, slashing the number of diseases that it recommends U.S. children be routinely vaccinated against to 11 from 17. That follows the CDC’s decision last year to reverse its recommendation that all kids get the COVID-19 vaccine.

On Monday, the AAP released its own immunization guidelines, which now look very different from the federal government’s. The organization, which represents most of the nation’s primary care and specialty doctors for children, recommends that children continue to be routinely vaccinated against 18 diseases, just as the CDC did before Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took over the nation’s health agencies.

Endorsed by a dozen medical groups, the AAP schedule is far and away the preferred version for most healthcare practitioners. California’s public health department recommends that families and physicians follow the AAP schedule.

“As there is a lot of confusion going on with the constant new recommendations coming out of the federal government, it is important that we have a stable, trusted, evidence-based immunization schedule to follow and that’s the AAP schedule,” said Dr. Pia Pannaraj, a member of AAP’s infectious disease committee and professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego.

Both schedules recommend that all children be vaccinated against measles, mumps, rubella, polio, pertussis, tetanus, diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), pneumococcal disease, human papillomavirus (HPV) and varicella (better known as chickenpox).

AAP urges families to also routinely vaccinate their kids against hepatitis A and B, COVID-19, rotavirus, flu, meningococcal disease and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The CDC, on the other hand, now says these shots are optional for most kids, though it still recommends them for those in certain high-risk groups.

The schedules also vary in the recommended timing of certain shots. AAP advises that children get two doses of HPV vaccine starting at ages 9 to12, while the CDC recommends one dose at age 11 or 12. The AAP advocates starting the vaccine sooner, as younger immune systems produce more antibodies. While several recent studies found that a single dose of the vaccine confers as much protection as two, there is no single-dose HPV vaccine licensed in the U.S. yet.

The pediatricians’ group also continues to recommend the long-standing practice of a single shot combining the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and varicella vaccines in order to limit the number of jabs children get. In September, a key CDC advisory panel stocked with hand-picked Kennedy appointees recommended that the MMR and varicella vaccines be given as separate shots, a move that confounded public health experts for its seeming lack of scientific basis.

The AAP is one of several medical groups suing HHS. The AAP’s suit describes as “arbitrary and capricious” Kennedy’s alterations to the nation’s vaccine policy, most of which have been made without the thorough scientific review that previously preceded changes.

Days before AAP released its new guidelines, it was hit with a lawsuit from Children’s Health Defense, the anti-vaccine group Kennedy founded and previously led, alleging that its vaccine guidance over the years amounted to a form of racketeering.

The CDC’s efforts to collect the data that typically inform public health policy have noticeably slowed under Kennedy’s leadership at HHS. A review published Monday found that of 82 CDC databases previously updated at least once a month, 38 had unexplained interruptions, with most of those pauses lasting six months or longer. Nearly 90% of the paused databases included vaccination information.

“The evidence is damning: The administration’s anti-vaccine stance has interrupted the reliable flow of the data we need to keep Americans safe from preventable infections,” Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo wrote in an editorial for Annals of Internal Medicine, a scientific journal. Marrazzo, an infectious disease specialist, was fired last year as head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases after speaking out against the administration’s public health policies.

-

Illinois7 days ago

Illinois7 days agoIllinois school closings tomorrow: How to check if your school is closed due to extreme cold

-

Pittsburg, PA1 week ago

Pittsburg, PA1 week agoSean McDermott Should Be Steelers Next Head Coach

-

Pennsylvania3 days ago

Pennsylvania3 days agoRare ‘avalanche’ blocks Pennsylvania road during major snowstorm

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoMiami star throws punch at Indiana player after national championship loss

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoRing claims it’s not giving ICE access to its cameras

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoContributor: New food pyramid is a recipe for health disasters

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Review: In ‘Mercy,’ Chris Pratt is on trial with an artificial intelligence judge

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoTrump’s playbook falters in crisis response to Minneapolis shooting