Louisiana

Louisiana Treasurer takes aim at Bank of America, but others have similar ESG policies

In rejecting Bank of America, Fleming aligned himself with other state finance officials from the State Financial Officers Foundation, a right-leaning organization that casts ESG policies as a tool used to aid progressive politics.

In an April 2024 letter, Fleming and 14 other SFOF members said the financial institution “had a track record of de-banking religious organizations” and that its “Net-Zero Banking Alliance commitments will also lead to de-banking.”

The Net-Zero Banking Alliance is a coalition of banks that have pledged to align their lending and investments with net-zero emissions goals to limit global temperature increases.

In a May response, Bank of America said that “religious beliefs or political view-based beliefs are never a factor in any decisions related to our client’s accounts.”

Other fiscal agents

Fleming last week did not mention JPMorgan Chase, which is also a member of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance.

Nor did he mention US Bank, which in a 2023 report said it intends to “partner with our clients on their transition to a lower carbon economy” and called itself “one of the most active renewable energy investors in the nation.”

Bank of New York Mellon also considers climate in its investments, and Capital One and Hancock Whitney have taken steps in that direction.

Regions Bank and Cadence Bank have taken steps to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions.

Fleming said any decisions about state fiscal agents are up to the IEB. But he defended his recommendation to reject Bank of America as a way to push back against policies he deems harmful to Louisiana. The IEB has not scheduled a vote on Bank of America’s application.

“As we create counter pressure, what we’re finding is (banks) are beginning to back away from some of these things,” Fleming said, though he did not point to specific examples.

Meanwhile, Moller said he commends public companies that consider problems associated with climate change. Because Louisiana is particularly susceptible to the negative impacts of climate change, “if anything, we should be trying to do more business with companies that take this threat seriously,” he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Louisiana

Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry calls for amendment for teacher pay raises

VIDEO: Louisiana 2026 Legislative Session Previewed in Lafayette

At One Acadiana’s Lafayette outlook event, business and policy leaders discussed the 2026 session and what it could mean for jobs, schools and voters.

BATON ROUGE — Gov. Jeff Landry advocated for a constitutional amendment that would create a permanent teacher pay raise as well as an eventual elimination of the state income tax in an opening address to the Louisiana Legislature on Monday.

Landry pushed for the passage of Proposed Amendment 3 on the May 2026 ballot to free up money for teacher pay raises.

He said the amendment would pay down longstanding debt within the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana and enable the state to afford a permanent increase in teacher income. The proposed increases are $2,250 for teachers and $1,125 for support staff.

“With a ‘yes’ vote, we can strengthen the retirement system, improve their take-home pay, and guess what? We can do it without raising taxes,” Landry said.

A bill proposing the elimination of the state income tax, which takes in about $4 billion annually, was pre-filed earlier in the year by Rep. Danny McCormick, R-Oil City. Where the money will come from to supplement the loss is currently unclear.

McCormick said in an interview with the LSU Manship School News Service that to encourage more young adults to stay in Louisiana, “we need to do away with the state income tax.”

“This is a conversation piece that hopefully we can figure out where to make cuts in the government so we can get the people their money back,” McCormick said.

But Senate President Cameron Henry, R-Metairie, said at a luncheon at the Baton Rouge Press Club that if the Legislature “can be disciplined” this session, residents could anticipate a 0.5% decrease in state income tax during next year’s session. He also said bigger tax cuts have to be planned over a longer budget cycle.

Within education changes, Landry commended the placing of the Ten Commandments in classrooms, approved by the Louisiana Supreme Court in a decision handed down last week.

“You have staked the flag of morality by recognizing that the Ten Commandments are not a bad way to live your life,” Landry said. “Students who don’t read them will likely read the criminal code.”

Landry’s budget proposed an $82 million increase for corrections services following 2024 tough-on-crime legislation that eliminated parole and probation, increased sentencing and encouraged harsher punishments.

Landry directed his criticism toward the New Orleans criminal justice system, which he feels is lacking accountability, especially in courtrooms.

“Judges hold enormous power, but they are not social workers with a gavel,” he said. “They are the final gatekeepers of public safety.”

The Orleans Parish criminal justice system relies on state and local funding stemming from revenues from fees imposed on those arrested, according to the Vera Institute. Landry said the state spends twice as much on the Orleans system as it does in East Baton Rouge Parish, the largest parish in the state.

“Being special does not mean being exempt from accountability,” Landry said.

Overall, Landry pushed for fewer and different ideas compared to the sweeping agenda he laid out at the start of previous legislative sessions. Henry mentioned at the Baton Rouge Press Club that the governor would like for this session to be a “member-driven session instead of an administrative session.”

Landry spoke only in general terms about his proposal for more funding for LA Gator, his program to let parents use state money to send their children to private schools.

“We must find a path so that the hard-earned money of parents follow their child to the education of their choice,” he said.

He has proposed doubling funding for the LA Gator program from $44 million a year to $88.2 million. The likelihood of this occurring is yet to be seen, as prominent lawmakers such as Sen. Henry are hesitant to approve an increase in funding.

Landry similarly did not mention carbon capture projects, despite the issue gaining traction from affected parish residents and lawmakers.

House Speaker Phillip DeVillier, R-Eunice, told the Baton Rouge Press Club last week that 22 bills have been filed in the House that he would consider “anti-carbon capture.”

Landry also cited data centers and other giant industrial development projects and touted his administration’s success in bringing more jobs to Louisiana and in helping to lower insurance premiums over the past year.

“May we continue to employ courage over comfort, and if we do, there is really no limit to what we can do for Louisiana,” Landry said.

Louisiana

Louisiana’s LNG exports are driving out fishermen and driving up utility bills across the U.S.

Phillip Dyson once tried working a job that wasn’t shrimping. He lasted three days on an oil rig before going right back to his boat.

“The man said, you just tell me you want the job, we’ll fire the other guy,” he said with a laugh. “I said, don’t fire that man, ’cause I ain’t coming back.”

For more than half a century, Dyson has been fishing the coastal waters of Cameron, Louisiana. Forty years ago, Cameron Parish was the top seafood port in the United States. Today, it’s ground zero for America’s LNG export boom, a multibillion-dollar industry — the U.S. is the top exporter in the world — that has reshaped the landscape, the economy, and the daily lives of the people who have lived here for generations.

When Dyson looks out from the shrimp dock now, he doesn’t recognize what he sees: spindly cranes, cylindrical cooling towers and the constant hum of the construction and processing of liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals rising above the marsh.

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

The terminals run day and night, super-cooling natural gas into liquid form where it’s loaded onto massive tanker ships for export to places like Europe and Asia.

Shrimpers like Dyson are catching about half of what they used to, driving many out of the industry.

“There used to be 200 shrimp boats in this town — down to 15,” Dyson said. “You went from a fishing town to a town that didn’t care less about the fishermen.”

Dyson is stubborn and set in his ways. Shrimping is all he knows. He doesn’t want to leave Cameron. He buried his parents here. Scattered his daughter’s ashes in the water.

“I would never want to leave her behind,” he said. “But I’m gonna have to.”

‘You’re just surrounded’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

Cameron Parish was an attractive destination for reasons both geographic and financial. It sits close to the Haynesville Shale formation, one of the country’s most productive natural gas fields, has no parish-wide sales tax and LNG companies have secured industrial tax exemptions that, according to community advocates, amount to nearly a billion dollars a year across the three operating terminals — roughly $6 million per permanent job created.

“They don’t only export gas — they export the profits,” said James Hiatt, a former oil and gas worker who founded For a Better Bayou, a southwest Louisiana environmental community organization. “That’s the key.”

The company at the center of the expansion is Venture Global, which operates the Calcasieu Pass terminal, known as CP1, just outside of Cameron. In a March earnings call, the company reported it made more than $6 billion in 2025 alone — tripling its profits from the previous year.

In an interview last year on CNBC, Venture Global’s CEO, Mike Sabel, described the company in terms residents find difficult to square with their daily reality: “Ultimately our business is that we manufacture and operate machines that produce money.”

President Donald Trump’s administration approved a second Venture Global terminal in Cameron — CP2 — just two months after taking office in 2025. Nationally, 17 new export terminals are either under construction or have won approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Six of them are in southwest Louisiana.

Robyn Thigpen, a local resident and executive director of the advocacy group Fishermen Involved in Saving Our Heritage (FISH), described the sense of encirclement many people feel.

“When you turn here,” she said, pointing in different directions from the beach in Cameron, “the cranes off in the distance is the expansion to CP1. 12 miles back into town is Hackberry LNG. Probably about 30 miles this direction is Sabine LNG. So you’re just surrounded.”

‘No shrimper can make it here’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

Last August, while Venture Global was dredging a shipping channel at CP1 — pumping out mud and sediment to clear a path for vessels — something went wrong. The company spilled hundreds of acres of sediment into the surrounding marsh.

The mud blanketed the area where Tad Theriot, a shrimper turned oysterman, had been growing his harvest. He pivoted to oyster farming two years ago, after years of declining shrimp catches made the traditional livelihood impossible to sustain.

The dredge spill devastated his oyster operation almost overnight.

“Half of them died,” Theriot said. “We lost 50% on the big ones, even more than that.”

Out on the water, the evidence was plain — oysters pulled from cages bore what his farming partner Sky Leger called “mud blisters,” deposits of silt visible inside the shell.

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

“Before you try, tell me — would you eat it if you knew that that was there?” Leger said, pointing to dark splotches on the iridescent cup of a fresh oyster. “How does that get there?”

Venture Global told More Perfect Union and Gulf States Newsroom in a statement that the “isolated discharge was quickly contained,” and that there were “no significant offsite impacts” as a result of the spill.

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries documented increased oyster mortality near the spill site in September, and fishermen have since requested a more comprehensive government study.

To date, no significant enforcement action has been taken against the company.

But according to documents obtained by More Perfect Union, Venture Global offered some affected fishermen $20,000 — on the condition they could never sue or speak negatively about the company again. When asked about the offer, Venture Global said the company “has communicated directly” with local fishermen “to develop mitigation and remediation plans, and minimize the potential for an event like this again.”

Theriot said he’d never take the money.

“That’s not right,” he said flatly. “I have hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of oysters. I want hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Advocates like Hiatt called the settlement offers part of a pattern the company is using to sidestep accountability through financial and political power.

“After this spill, more people are understanding that these corporations don’t give a f— about you,” he said. “All they care about is how much money they can make.”

Last month, a pipeline part of an under-construction project operated by Delfin LNG ruptured near Holly Beach in Cameron Parish. The ensuing explosion resulted in “catastrophic injuries” to a contractor working for the company, according to a lawsuit filed in Texas that accused the company of negligence and failing to “ensure the pipeline was free of flammable vapors and materials.”

“It’s a reminder that these things are happening in a community that doesn’t even have a hospital,” Thigpen said, noting that the worker was taken to a hospital in Port Arthur, Texas, roughly 45 minutes away. “It’s another example of why we can’t trust these companies to do the right thing.”

‘You can’t afford this and food’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

The impacts of Cameron’s transformation don’t stop at the bayou’s edge. The LNG export boom is being felt in the utility bills of Americans across the country.

Eight LNG export terminals now consume more natural gas each day than all 74 million American households connected to gas utility service combined. The federal government projects the benchmark price of natural gas will average 22% higher in 2026 than in 2025, citing LNG exports as a driving factor.

A Public Citizen analysis found domestic natural gas prices were $12 billion higher for residential customers in just the first nine months of 2025 compared to the same period the year before — roughly $124 per household.

“It’s simple supply and demand,” Slocum said. “You’re forcing Americans to compete with their counterparts in Berlin and Beijing for access to U.S. natural gas. And that pushes the domestic price up. The more we export, the higher the prices the rest of Americans will pay to heat and cool their homes.”

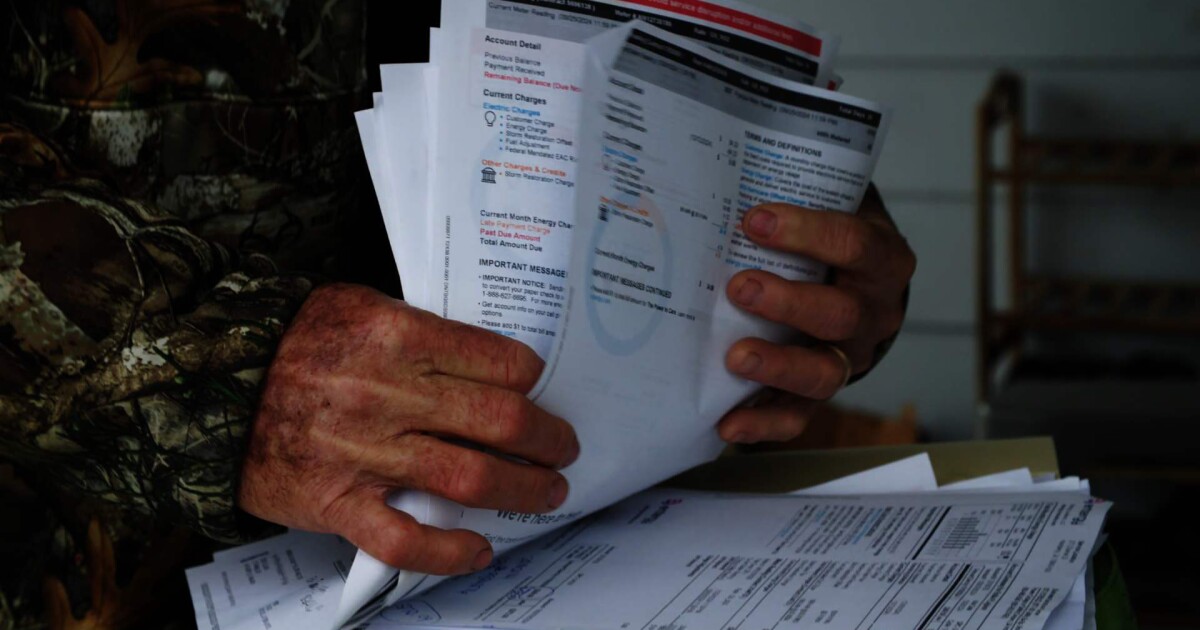

In Hackberry, Louisiana — minutes down the road from Cameron Parish’s other export terminal — fisherman Eddie Lejuine and his wife Michelle have watched their bills climb. Lejuine depends on a refrigerated storage container to keep his catch marketable. Without it, he can’t work.

“You can’t afford this and food,” Michelle Lejuine said. “What are you gonna do? You gonna eat or are you gonna have electricity?”

Eddie Lejuine put it plainly: “We’re catching less fish, [making] less money, paying higher bills.”

Trump’s promise, the industry’s windfall

During the 2024 campaign, Trump pledged to cut Americans’ energy bills in half within 12 months. He repeated it at rallies and put it in writing in a Newsweek op-ed.

On his first day back in the White House, one of his earliest executive orders undid former President Joe Biden’s pause on pending LNG export approvals — a pause that was implemented, in part, because consumer advocates argued the existing review process failed to account for domestic price impacts.

The ties between Venture Global and the Trump administration run deep. According to reporting by the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, the company’s CEO was present at a private 2024 meeting at which Trump reportedly asked oil and gas executives to contribute $1 billion to his campaign.

Slocum argued the gap between Trump’s promise and his policy is not an accident.

“What Trump has done is to prioritize the financial interests of the natural gas industry,” he said. “And the natural gas industry’s primary financial directive is to maximize LNG exports.”

Electricity prices jumped 6.9% in 2025 year over year, according to Goldman Sachs.

‘Find somewhere else to build this’

Ian McKenna

/

More Perfect Union

More than 90% of Cameron Parish voted for Trump in 2024. The mood among the fishermen who remain is harder to categorize than partisan politics.

When asked if he’d vote for Trump again, Lejuine said: “No, I’m not. I’m hoping we have a better selection of something.”

Hiatt, a self-described third-generation oil and gas worker, framed it as a matter of basic fairness rather than ideology.

“This is ‘America Last’ policy,” he said, “to export our natural resources to the highest bidder at the expense of every American.”

Dyson, standing at the dock in the late afternoon light, said what he would tell Venture Global and the politicians like Trump and Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry, who championed the expansion: “Find somewhere else to build this s—. I never thought I’d have seen this place like this. Never in my lifetime.”

His electricity bill runs $350 to $500 a month for a 990-square-foot house, he said. He and his wife receive about $1,300 a month together on Social Security. With what he’s catching, it’s not enough.

He said he won’t stop shrimping, but he can’t do it in Cameron.

“This is what I do. That’s what I’m gonna do till they throw dirt on me. That might not be here, but I will fish till it’s over.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. This story was produced in collaboration with More Perfect Union.

Louisiana

More Storms Monday – Severe Storms Possible by Midweek

(KMDL-FM) You might not have realized it, but you’re on a roller coaster. No, not the kind of roller coaster you look forward to riding, but the kind of roller coaster only Mother Nature can devise in the form of Louisiana’s annual up and down weather conditions, also known as spring.

READ MORE: Louisiana Parishes That Have the Most Tornadoes

Much of Louisiana was affected by strong storms with heavy rains and gusty winds during the day on Saturday and extending into Sunday morning. By later afternoon yesterday, conditions had improved, and it looked as though the work and school week would be off to a much calmer start.

Heavy Rain Possible in Louisiana To Start the Work Week

The start of the work and school day will be much calmer; however, the ride home on this first day of “extra sunlight” thanks to Daylight Saving Time will include a decent chance of showers and storms. Oh, and there are already reports of thick fog.

So, after a foggy start this morning, you could be picking up kids from school or driving yourself home from work in a torrential downpour. And you’ll get to do all of this while you’re mentally addled from the twice-a-year time change.

Rain chances are listed at 50% for this afternoon, but they do taper off quickly after the sun goes down. The Weather Prediction Center is forecasting a slight risk of an excessive rain event for portions of Louisiana later today. The area of concern is generally along and well north of US 190.

When Is The Next Threat of Severe Storms in Louisiana?

Tuesday should be a cloudy but breezy and warm day. Then on Wednesday, the rain chances and the next threat of severe storms will move into Louisiana.

weather.gov/lch

The Storm Prediction Center outlook for Wednesday’s severe weather potential suggests that the northern and central sections of the state might be more at risk for stronger storms than the I-10 corridor might be.

READ MORE: Who Is Appearing at Patty in the Parc in Lafayette?

We will know more about that potential later this morning when the SPC updates its forecast. The outlook for the remainder of the week, including the Patty in the Parc Weekend event in Downtown Lafayette, looks to be spectacular.

Patty in the Parc Entertainment 2011-2025

Gallery Credit: Dave Steel

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago2 Survivors Describe the Terror and Tragedy of the Tahoe Avalanche

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Virginia6 days ago

Virginia6 days agoGiants will hold 2026 training camp in West Virginia