Lifestyle

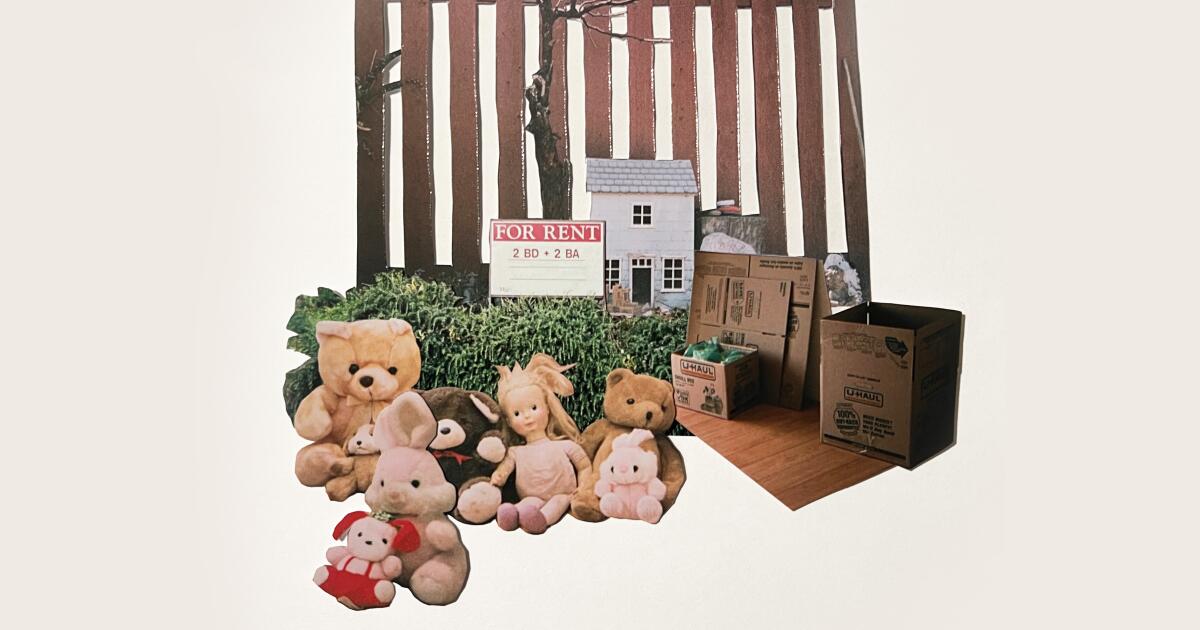

Renting used to be a source of shame to this apartment manager’s daughter. Now it’s a knowing comfort

I can barely remember a time when we didn’t live where we worked. Our first property manager job was for a 30-unit apartment building between Beverly Hills and Pico-Robertson. My parents didn’t speak English but got the job anyway because they knew a guy who knew a guy who knew a guy. There was an elementary school at the end of our magnolia tree-lined street that I couldn’t go to because the Beverly Hills School District allowed only Beverly Hills addresses. I would walk down the block to visit my friend (another apartment manager’s daughter) or to buy a sleeve of blue raspberry sour straws at the Blockbuster around the corner and hear children playing in the well-manicured school yard, but I never once saw an actual child. This was how I learned to perceive wealth in Los Angeles: near, but just out of reach.

Even at the age of 6 or 7 or 8, I knew that this was all temporary. Renting is inherently provisional, especially when you’re not actually paying rent. I made the most of it. While my mother cobbled together a career as a bookkeeper and my father assumed the role of both the maintenance guy and the manager of the building, I stole CDs from the mailroom, Rollerbladed in the slick oil-stained subterranean parking garage and belted Spice Girls lyrics in the emergency stairwell with my cousin until a tenant would open the door and find us there alone in the dark. I still own contraband from that time: someone’s copy of the “City of Angels” soundtrack. Inside our apartment, I shared a room with my parents. Our beds were butted up against each other, as they had always been.

Before this job and this building we lived in a one-bedroom apartment in West Hollywood with brown shag carpet and a cardboard box as my toy chest. The apartment buildings on our block, once favored by up-and-coming movie stars and writer Eve Babitz, now were occupied by Eastern Europeans fleeing the collapse of the Soviet Union. “There comes a moment for the immigrant’s child when you realize that you and your parents are assimilating at the same time,” writes Hua Hsu in his memoir, “Stay True.” While I attended preschool at Plummer Park, my mother went to community college and my father painted houses for $5 an hour. Before the brown shag carpet, we slept on my aunt’s couch in Mid-City for six months. And before the couch, we lived in a brutalist Soviet government-issued apartment in Minsk, Belarus. From the beginning, my life was steeped in the impermanence of renting, which mirrored the impermanence of our immigrant experience.

All immigrants are opportunists. Or, at least all the ones I’ve encountered. They are keenly aware of how, at any moment, everything can change. “Immigration, exile, being uprooted and made a pariah may be the most effective way yet devised to impress on an individual the arbitrary nature of his or her own existence,” writes Serbian poet Charles Simic. With each move, I felt the arbitrary nature of our existence. And every time I translated a 30-day notice or drafted a memo and slipped it under a tenant’s door, I felt the pull of my parents’ ambition. “We came here for you.” They’d say it often. Lovingly piling on the pressure until I could no longer see a future where I didn’t have something to prove.

My father found the second property manager job listing in a local newspaper. A 50-unit building in the affluent neighborhood of Westwood. He brought Mama and me along to the interview, although technically the managers were not supposed to have a child. I was told that if I was on my best behavior, I would go to the sought-after public elementary school down the street and finally get my own room. The front of the building was covered in a flash of fuchsia bougainvillea, and the surrounding brick towers glowed with inviting warm windows and hints of crystal chandeliers. The owners of the building were a wealthy elderly Germanic-Jewish couple who met us outside and assessed my potential with war-weary eyes. I looked up at them dutifully, every butterfly clip I owned fluttering on my head like a migration. “She’s a mini you,” the woman said, noticing the quiet stoicism I’d picked up from my father. She looked at us as if she were looking into her own immigrant past, her harrowing escape from Austria as a teenager during the Holocaust. She smiled. Bent down. And handed me the keys.

Los Angeles has been a haven for transplants and immigrants since the tail end of the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of the railroad. It was once advertised as a wellness paradise, the sanatorium capital of America, a temporary resort for turn-of-the-20th century tuberculosis patients eager to seek treatment in the form of sunshine and “fresh” air. Many of these patients got better and stayed. “Los Angeles, it should be understood, is not a mere city. On the contrary, it is, and has been since 1888, a commodity; something to be advertised and sold to the people of the United States like automobiles, cigarettes, and mouthwash,” writes Mike Davis in “City of Quartz.”

The commodification of Los Angeles and Hollywood, and the rising population, has made the city an expensive place to live. The majority of the population rents: According to a 2021 report, 63% of Los Angeles households are renter-occupied, while 37% are owner-occupied. And rent has more than doubled in the past decade, leading to an astonishing 57% of L.A. County residents being rent-burdened, meaning they spend a third or more of their income on rent. And yet people continue to move to Los Angeles, a place synonymous with liminal space — the space between who we are and who we want to become. Even if who you want to become is out of reach.

“If there is a predominant feeling in the city-state [Los Angeles], it is not loneliness or daze, but an uneasy temporariness, a sense of life’s impermanence: the tension of anticipation while so much quivers on the line,” writes Rosecrans Baldwin in “Everything Now: Lessons From the City-State of Los Angeles.”

Los Angeles is a city always on the edge of disaster: gentrification, housing shortages, unlawful evictions, homelessness (second largest homeless population outside of New York), greed, wildfire, earthquakes, floods, landslides, the imminent death of the legendary palm trees, the intangible but plausible possibility of breaking off from the continental United States and slipping into the Pacific Ocean. The city, like its residents, is impermanent, always shape-shifting, always on the verge of becoming something else.

“Our dwellings were designed for transience,” writes Kate Braverman about the midcentury West Los Angeles of her childhood in “Frantic Transmissions to and From Los Angeles: An Accidental Memoir.” “Apartments without dining rooms, as if anticipating a future where families disintegrated, compulsively dieted, or ate alone, in front of televisions.”

In Westwood, our living room was our dining room and our office. Leases were signed on the dinner table. At any moment, the phone or doorbell would ring with someone dropping off a rent check or complaining about a broken air conditioner or standing barefoot in a bathrobe locked out of their apartment. I would pretend to not care. I would eat my cheese puffs on the couch and stare attentively at the glowing TV, with the business of the building in my periphery. I would remind myself that this was temporary. Our liminal space. Maybe my parents would invest in an adult day care center like their friend Sasha? Maybe we would one day own a house? As I got older, I grew more ashamed. More aware of my own body and its presence. I would cower in my room or the hallway, shoveling Froot Loops into my mouth until the apartment was no longer an office but our home again. This shape-shifting was its own type of impermanence. One minute the apartment was a place where we lived and the next it was a place where we worked. The line was blurred and so was my idea of home. Of what is yours and what is mine.

Some of the tenants were there before us and some were a rotating cast of characters. But all of them were strangers we shared walls with. Of course, we weren’t the only immigrant family. There were also Persian immigrants who fled Iran during the Islamic Revolution, but they mostly kept to themselves. Due to the nature of the job, we were always on display. My parents’ accents. My growing body. My father’s health. The mezuzah on our door frame. Our apartment, a collection of discarded furniture from vacated units. Early on, I was warned to not make friends with any of the tenants. I was told it was unprofessional. A trap. That they only wanted to be my friend so they could get special treatment. Sometimes, we broke the rules. I babysat the child star while his single mother “networked” (partied in the Hollywood Hills). I played Marco Polo in the pool with the Persian kids. I leafed through headshots with a Russian mail-order bride while my parents drank tea with her mother. They would all eventually move out and so would we.

I used to tell my friends that we owned the building. That I would one day inherit it. This was easier than saying that we lived there because we worked there. I’m not sure if anyone believed me anyway. Many of my friends lived in what I considered to be mansions with nannies and parents with six-figure dual incomes that afforded them trips to faraway destinations I couldn’t place on a map. When my friends were over and the landline would ring, I would rush them to my bedroom before they could hear my father answer the phone with, “Manager.”

The only property my parents own is a shared plot at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. When my father was diagnosed with a chronic disease, my mother was left to manage the Westwood building on her own. Eventually, my parents retired after 21 years and moved out of the building during the first few months of the pandemic. They still rent, and so do I.

What is truly ours?

I’ve spent my life grappling with the concept of ownership. How our identity often gets wrapped up in what we own and what we don’t own. How in the U.S., ownership is the pinnacle of success. How there was no such thing as ownership in the failed Soviet experiment. How you could pick apples off any tree because they were there for everybody to enjoy. How owning a home in Los Angeles may forever be out of reach. How impermanent we are in the arbitrary nature of existence.

After I graduated from college and landed an office job in Los Angeles, I began renting apartments on my own. The eggshell walls painted over and over and over again. The rotating neighbors I still feared to befriend. The flying cockroaches. The broken laundry machines. The unabiding footsteps. The eternal sounds of other people’s lives. The possibility of moving out and starting all over again. It all felt so familiar. The impermanence I witnessed so often as a child was no longer a source of shame but a knowing comfort that at any moment everything could change.

Diana Ruzova is a writer from Los Angeles. She holds an MFA in literature and creative nonfiction from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Her writing has appeared in the Cut, Oprah Daily, Flaunt, Hyperallergic, Los Angeles Review of Books and elsewhere.

Lifestyle

‘Hamnet’ star Jessie Buckley looks for the ‘shadowy bits’ of her characters

Jessie Buckley has been nominated for an Academy Award for best actress for her portrayal of William Shakespeare’s wife in Hamnet.

Kate Green/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kate Green/Getty Images

Actor Jessie Buckley says she’s always been drawn to the “shadowy bits” of her characters — aspects that are disobedient, or “too much.” Perhaps that’s what led her to play Agnes, the wife of William Shakespeare, in Hamnet.

Buckley says the film, which is based on Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, offered a chance to counter a common narrative about the playwright’s wife: that she “had kept him back from his genius,” Buckley says.

But, she adds, “What Maggie O’Farrell so brilliantly did, not just with Agnes and Shakespeare’s wife, but also with Hamnet, their son, was to bring these people … and give them status beside this great man. … [And] give the full landscape of what it is to be a woman.”

The film is nominated for eight Academy Awards, including best actress for Buckley. In it, she plays a woman deeply connected to nature, who faces conflicts in her marriage, as well as the death of their son Hamnet.

Buckley found out she was pregnant a week after the film wrapped. She’s since given birth to her first child, a daughter.

“The thing that this story offered me, that brought me into this next chapter of my life as a mother was tenderness,” she says. “A mother’s tenderness is ferocious. To love, to birth is no joke. To be born is no joke. And the minute something’s born into the world, you’re always in the precipice of life and death. That’s our path. … I wanted to be a mother so much that that overrode the thought of being afraid of it.”

Jessie Buckley stars as Agnes and Joe Alwyn plays her brother Bartholomew in Hamnet.

Courtesy of Focus Features/Courtesy of Focus Features

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Focus Features/Courtesy of Focus Features

Interview highlights

On filming the scene where she howls in grief when her son dies

I didn’t know that that was going to happen or come out, it wasn’t in the script. I think really [director] Chloé [Zhao] asked all of us to dare to be as present as possible. Of course, leading up to it, you’re aware this scene is coming, but that scene doesn’t stand on its own. By the time I’d met that scene, I had developed such a deep bond with Jacobi Jupe, who plays Hamnet, and [co-stars] Paul [Mescal] and Emily Watson, and all the children and we really were a family. And Jacobi Jupe who plays Hamnet is such an incredible little actor and an incredible soul, and we really were a team. …

The death of a child is unfathomable. I don’t know where it begins and ends. Out of utter respect, I tried to touch an imaginary truth of it in our story as best I could, but there’s no way to define that kind of grief. I’m sure it’s different for so many people. And in that moment, all I had was my imagination but also this relationship that was right in front of me with this little boy and that’s what came out of that.

On what inspired her to pursue singing growing up

I grew up around a lot of music. My mom is a harpist and a singer and my dad has always been passionate about music, so it was always something in our house and always something that was encouraged. … Early on, I have very strong memories of seeing and hearing my mom sing in church and this quite intense mercurial conversation that would happen between her, the story and the people that would listen to her. And at the end of it, something had been cracked between them and these strangers would come up with tears in their eyes. And I guess I saw the power of storytelling through my mom’s singing at a very young age, and that was definitely something that made me think I want to do that.

On her first big break performing as a teen on the BBC singing competition I’d Do Anything — and being criticized by judges about her physical appearance

I was raw. I hadn’t trained. I had a lot to learn and to grow in. I was only 17. I think there was part of their criticism which I think was destructive and unfair when it became about my awkwardness, or they would say I was masculine and send me to kind of a femininity school. … They sent me to [the musical production of] Chicago to put heels on and a leotard and learn how to walk in high heels, which was pretty humiliating, to be honest, and I’m sad about that because I think I was discovering myself as a young woman in the world and wasn’t fully formed. … I was different. I was wild, I had a lot of feeling inside me. I could hardly keep my hands beside myself and I think to kind of criticize a body of a young woman at that time and to make her feel conscious of that was lazy and, I think, boring.

On filming parts of the 2026 film The Bride! while pregnant

I really loved working when I was pregnant. I thought it was a pretty wild experience, especially because I was playing Mary Shelley and I was talking about [this] monstrosity, and here I was with two heartbeats inside me. Becoming a mom and being pregnant did something, I think, for me. My experience of it, it’s so real that it really focuses [me to be] allergic to fake or to disconnection.

Since my daughter has come and I know what that connection is and the real feeling of being in a relationship with somebody … as an actress, it’s very exciting to recognize that in yourself and really take ownership of yourself.

I’m excited to go back and work on this other side of becoming a mother in so many ways, because I’ve shed 10 layers of skin by loving more and experiencing life in such a new way with my daughter. I’m also scared to work again because it’s hard to be a mother and to work. That’s like a constant tug because I love what I do and I’m passionate and I want to continue to grow and learn and fill those spaces that are yet to be filled — and also be a mother. And I think every mother can recognize that tug.

On the possibility of bringing her daughter to travel with her as she works

I haven’t filmed for nearly a year and I cannot wait. I’m hungry to create again. And my daughter will come with me. She’s seven months, so at the moment she can travel with us and it’s a beautiful life. And she meets all these amazing people and I have a feeling that she loves life and that’s a great thing to see in a child. And I hope that’s something that I’ve imparted to her in the short time that she’s been on this earth is that life is beautiful and great and complex and alive and there’s no part of you that needs to be less in your life. You might have to work it out, but it’s worth it.

Lauren Krenzel and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

Lifestyle

‘Evil Dead’ Star Bruce Campbell Reveals He Has Cancer

Bruce Campbell

I’m Battling Cancer

Published

Bruce Campbell has revealed he has cancer, but says it’s a type that’s treatable, though not curable.

“The Evil Dead” actor shared the news Monday in a message to fans, writing, “Hi folks, these days, when someone is having a health issue, it’s referred to as an ‘opportunity,’ so let’s go with that — I’m having one of those.” He continued, “It’s also called a type of cancer that’s ‘treatable’ not ‘curable.’ I apologize if that’s a shock — it was to me too.”

Campbell said he wouldn’t go into further detail about his diagnosis, but explained his work schedule will be changing. “Appearances and cons and work in general need to take back seat to treatment,” he wrote, adding he plans to focus on getting “as well as I possibly can over the summer.”

As a result, Campbell says he has to cancel several convention appearances this summer, noting, “Treatment needs and professional obligations don’t always go hand-in-hand.”

He says his plan is to tour this fall in support of his new film, “Ernie & Emma,” which he stars in and directs.

Ending on a determined note, Campbell told fans, “I am a tough old son-of-a-bitch … and I expect to be around a while.”

Lifestyle

‘Scream 7’ takes a weak stab at continuing the franchise : Pop Culture Happy Hour

Neve Campbell in Scream 7.

Paramount Pictures

hide caption

toggle caption

Paramount Pictures

The OG Scream Queen Neve Campbell returns. Scream 7 re-centers the franchise back on Sidney Prescott. She has a new life, a family, and lots of baggage. You know the drill: Someone dressing up as the masked slasher Ghostface comes for her, her family and friends. There’s lots of stabbing and murder and so many red herrings it’s practically a smorgasbord.

Follow Pop Culture Happy Hour on Letterboxd at letterboxd.com/nprpopculture

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO6 days ago

Denver, CO6 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling