Lifestyle

A prison art show at Lincoln's Cottage critiques presidents' penal law past

The Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project exhibition features artwork by incarcerated artists critiquing the U.S. justice system and is on display at President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

The Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project exhibition features artwork by incarcerated artists critiquing the U.S. justice system and is on display at President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C.

Catie Dull/NPR

Caddell Kivett was watching the inauguration of President Biden on Jan. 20, 2021, when the thread of an idea began to form.

He was inspired by Amanda Gorman, who took the podium and read her poem The Hill We Climb, which says, in part:

“We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace, and the norms and notions of what ‘just’ is isn’t always justice. …”

It was then that he really started thinking, Kivett told NPR.

“Some of the words of that poem just really touched how I feel about our country,” he said.

And those feelings are complicated, to say the least.

Kivett, 53, is serving an 80-year prison sentence for assault-related charges.

He’s spent about 14 years incarcerated in North Carolina at the mercy of the U.S. criminal justice system and policies established by U.S. presidents, including Biden.

When the inauguration ceremony concluded, Kivett returned to his cell at Nash Correctional Institution in Nashville, N.C., where he’s been for the past eight years. He began to mull over a “kind of improbable idea” as the words of Gorman’s poem, “The norms and notions of what ‘just’ is isn’t always justice,” cycled through his mind.

He said he considered: What if there was a way to harness the voices of the incarcerated to critique this so-called justice system and to challenge the idea of what true justice in America could look like?

“Most people on the outside don’t know what is going on in here,” Kivett said. “And so, we just accept that this is how things are to be done and the correct response to people who commit harms or violence is to just lock them away.”

Caddell Kivett’s brainchild, Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project, launched at President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C., this month.

Tracey Thornton/Janie Ritter

hide caption

toggle caption

Tracey Thornton/Janie Ritter

He is surrounded by artists at Nash Correctional and considered ways to take that talent and use it to push forward these questions and ideas, he said.

These thoughts that started as just a flicker in his mind in 2021 took years and complex coordination with advocates from Justice Arts Coalition, such as founder and director Wendy Jason and programs assistant Janie Ritter, to come to fruition. But this month Kivett’s brainchild, an exhibit titled Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project, was revealed to the public at President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C.

The exhibit of 46 pieces of art and writing was curated by the Committee of Incarcerated Writers and Artists, whose members all currently live within the carceral system across the U.S. In addition to Justice Arts Coalition, a group that supports imprisoned artists, the exhibit was coordinated by staff at Lincoln’s Cottage.

The exhibit, which costs visitors between $4 and $10, will continue through Feb. 19. It may later head to a few more venues but that’s yet to be confirmed. The pieces, however, can be bought once the current exhibit has finished with all proceeds going directly to the artists.

The art pieces include different takes on portraits of U.S. presidents, among them Presidents Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and put these leaders’ records on criminal justice under the microscope.

The exhibition focuses on various presidents, including Presidents Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan, Joe Biden (bottom left) and Richard Nixon.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

The exhibition focuses on various presidents, including Presidents Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan, Joe Biden (bottom left) and Richard Nixon.

Catie Dull/NPR

The difficulties of coordinating the exhibit from behind bars

Wendy Jason is the founder and director of the Justice Arts Coalition in Takoma Park, Md.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Wendy Jason is the founder and director of the Justice Arts Coalition in Takoma Park, Md.

Catie Dull/NPR

From the moment Kivett reached out to the Justice Arts Coalition in early 2021, the wheels started turning, even if slowly, and not without some hurdles. Ritter, nonetheless, worked to ensure that Kivett kept agency over the project.

“It was his idea. I wanted him to make the decisions,” she said. “And, of course, a lot of the decisions couldn’t be made from inside. They had to be facilitated outside.”

Discussing the framework of the project with one another was among the challenges because Kivett has limited ability to call or email from his cell. And the artists whom Ritter and Jason contacted to contribute to the project are located in prisons throughout the country and rely heavily on snail mail to correspond.

Watercolor paintings, mixed media collages and colored pencil portraits are now hanging in Lincoln’s Cottage.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Watercolor paintings, mixed media collages and colored pencil portraits are now hanging in Lincoln’s Cottage.

Catie Dull/NPR

Gradually, the artists began sending in their work to the group’s headquarters in Takoma Park, Md.

To get these works to Kivett and his Committee of Incarcerated Artists and Writers at Nash, who were selecting the best pieces to exhibit, Ritter had to send 8-and-a-half-by-11 sized photos of all of each piece and copies of the written submissions.

“At the same time, our mail system here was going under a transformation from paper to digital, which created a whole new slew of hurdles for us to get past,” Kivett said.

Later on, Callie Hawkins, the executive director of Lincoln’s Cottage, sent a copy of their floor plan to guide the committee in choosing where to display each piece.

“It’s a massive space,” Hawkins said. “I was blown away by their ideas for placement and groupings. And literally all our team did was place it on the wall where they directed us to.”

Janie Ritter is the programs assistant for Justice Arts Coalition. She wanted to ensure Kivett kept agency over the exhibition.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Janie Ritter is the programs assistant for Justice Arts Coalition. She wanted to ensure Kivett kept agency over the exhibition.

Catie Dull/NPR

Kivett said it was hard not to feel discouraged during the process.

But, he said, “This project is a testament to what can be accomplished if you don’t let discouragement stop your momentum.”

Kivett hopes as visitors come to view the exhibit that they leave with a deeper understanding of the direct impacts of mass incarceration to critique the idea of whether incarceration is the true path to justice and that they’re motivated to take concerns directly to their politicians to make change.

“I hope everyone realizes that they’re all stakeholders. And I want them to realize what their individual part is in this process. And I hope they leave our show charged to do their part,” Kivett said.

“Continuing to just cage people for harms committed in our country is not making us safer and not making us better as a nation,” he said.

He recommends rerouting money that is being put into prisons and jails into communities that need it the most rather than continuing to invest in the carceral system as it is now.

President Lincoln’s Cottage offers a poignant venue

A portrait of President Bill Clinton and a collage of drawings of President George W. Bush are on display at Lincoln’s Cottage.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

A portrait of President Bill Clinton and a collage of drawings of President George W. Bush are on display at Lincoln’s Cottage.

Catie Dull/NPR

Watercolor paintings, mixed media collages and colored pencil portraits are now hanging in Lincoln’s Cottage in what was the president’s former library, dining room and bedroom some 160 years ago.

Some of the pieces are of Lincoln himself.

A mixed media collage created by Robert Spence incorporates photos of Black Lives Matters protests surrounding a portrait of Lincoln. Spence writes of this piece, “There are so many hidden (and not so hidden) racial biases and struggles that still exist in America. I wonder what President Lincoln would say if he was alive today. ‘What happened to America?’ “

Other pieces target Lincoln’s more recent successors.

The works reflect on how each administration and the policies they signed into law have impacted prisoners and contributed to the current state of the U.S. criminal justice system, which has locked up almost 2 million people — a disproportionate number of whom are Black Americans.

A mixed media work featuring a portrait of President Abraham Lincoln is on display at the exhibition.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

A mixed media work featuring a portrait of President Abraham Lincoln is on display at the exhibition.

Catie Dull/NPR

Like former President Bill Clinton and his signing of the 1994 Crime Bill. Critics of this bill have said it is responsible for this mass incarceration of Black Americans.

Artist Mike Tran used this event to inspire his painting on Clinton.

Tran writes, “The 3 Strikes Law (the 1994 Crime Bill), designed as a crime deterrent, serves to prove how inadequate the ‘rehabilitation’ system is. Rehabilitation is not putting a person in a box for life. It is helping that person realize why they did what they did, who they harmed with their actions, and replacing those behaviors with prosocial thoughts and beliefs.”

Tran painted a skewed version of Clinton’s presidential portrait, writing:

“I wanted to weave these ideas into President Clinton’s portrait, as he was instrumental in the passing of this law. I wanted the symbolism in the piece to be subtle, hence the three small cigars on his collar and intentional blurring of the American Flag, but once you realize them, you can’t look away.”

Not all pieces put the presidents in a seemingly negative light.

In a portrait by Brian Hindson, he contemplates on his complex feelings about Trump, who signed the First Step Act into law in 2018. This law, among many other things, lowered prison sentences for certain nonviolent offenders.

Hindson, who at the time of finishing his painting spent 15 years in the federal prison system, writes after that law passed he saw that “people were leaving in droves” and that overcrowding in the federal prison system “was actually being addressed.”

That leaves Hindson with contradictory feelings about Trump. He painted Trump’s face split and divided into different pieces, each painted a different color.

“As controversial, polarizing, and divisive as Trump was and can be, he’s the only President that did something that benefitted every federal inmate. The style I picked was my fractured art. All the pieces make him up. All the bad stuff too. Much like all of us, it’s pieces of us. All the pieces make the whole,” Hindson wrote.

A six-panel installation by artists Yuri Kadamov, Aquilla Barnette and Lezmond Mitchell depicts President Barack Obama.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

A six-panel installation by artists Yuri Kadamov, Aquilla Barnette and Lezmond Mitchell depicts President Barack Obama.

Catie Dull/NPR

The exhibit’s largest piece is a 72-by-40-inch, six-panel installation that hangs in the center of the cottage’s sitting room wall.

It’s an eye-catching portrait with an even more striking story.

The subject of the piece is obvious: former President Obama. Except his face is distorted with puzzle pieces missing from his face.

It reflects the three artists’ broken hopes of Obama reforming the criminal justice system and granting clemency to men on death row — a dream of the three men who painted it, they wrote.

The artists, Yuri Kadamov, Aquilla Barnette, and Lezmond Mitchell, managed to work together on this piece without ever sharing the same space. The three men slid canvases under the steel doors of their cells and handed it off to a fellow inmate who would pass the work on to the next collaborator.

The piece, however, was never fully finished.

Mitchell, who was the only Native American on federal death row, was executed on Aug. 26, 2020, at the age of 38 for first-degree murder.

Callie Hawkins is the executive director at President Lincoln’s Cottage. Her team worked with Kivett on arranging and hanging the artwork in the president’s former library, dining room and bedroom.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

Callie Hawkins is the executive director at President Lincoln’s Cottage. Her team worked with Kivett on arranging and hanging the artwork in the president’s former library, dining room and bedroom.

Catie Dull/NPR

It’s significant given that this incomplete portrait sits in a building that represents what Hawkins calls “that unfinished work” of Lincoln’s legacy.

“[Lincoln] recognized in his own lifetime, that his role was just to push the boulder a little further up the hill, and there he was going to fall short, that others who came after him were going to fall short,” she said. “And then it was going to take everyone to continue this ideal, this promise.”

The site of the cottage is at the highest point of Washington, D.C. It was the seasonal home of the 16th president and his family. While at the cottage in 1862 (then called the Soldiers Home), Lincoln developed the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in an upstairs bedroom, Hawkins said.

This was “legally supposed to free slaves in America,” Ritter said.

“Mass incarceration in the U.S. has been referred to as the New Jim Crow. I think it’s such an interesting tension to have artwork created by folks who are still inside, who do slave labor, in the room where Lincoln quite literally wrote out his thoughts for freeing those people in America,” she said.

The Proclamation was enshrined in the 13th Amendment by 1865. It says that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

A portrait of President Abraham Lincoln sits on a mantel at Lincoln’s Cottage.

Catie Dull/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Catie Dull/NPR

A portrait of President Abraham Lincoln sits on a mantel at Lincoln’s Cottage.

Catie Dull/NPR

Kivett said this amendment provides this “loophole” for those convicted of a crime. He said involuntary servitude is still legal for convicted felons, who when incarcerated, are forced into work that pays little to nothing in prisons across the country.

Hawkins said it was important for the cottage to be a part of this exhibit as it offered an important point to hold important conversations around rectifying injustice — a goal of the museum.

“It’s really important to [Lincoln’s Cottage] to not put Lincoln on a pedestal. To take him down, to interrogate him, his policies, and to really be honest about where that leaves us today,” she said.

For Kivett, the project and its themes are the embodiment of years of focus and passion on social justice issues while in prison.

It’s part of what gives him purpose and goals for the future while inside, he said.

“The big picture of the project is to let people on the outside know that we are still people, and that we are still connected somehow in our humanity.”

Lifestyle

Nature needs a little help in the inventive Pixar movie ‘Hoppers’ : Pop Culture Happy Hour

Piper Curda as Mabel in Hoppers.

Disney

hide caption

toggle caption

Disney

In Disney and Pixar’s delightful new film Hoppers, a young woman (Piper Curda) learns a beloved glade is under threat from the town’s slimy mayor (Jon Hamm). But luckily, she discovers that her college professor has developed technology that can let her live as one of the critters she loves – by allowing her mind to “hop” into an animatronic beaver. And it just might just allow her to help save the glade from serious risk of destruction.

Follow Pop Culture Happy Hour on Letterboxd at letterboxd.com/nprpopculture

Subscribe to Pop Culture Happy Hour Plus at plus.npr.org/happyhour

Lifestyle

Kim Kardashian Never Tried to Buy Rare Hermès Bag for North West, Despite Report

Kim Kardashian

never denied rare hermés bag for north west …

It Never Happened!!!

Published

Kim Kardashian is not the celebrity who got turned away trying to buy a rare Hermès bag for her daughter, despite a viral claim suggesting otherwise … TMZ has learned.

Sources familiar with the situation tell TMZ … the story circulating online that Kim once attempted to purchase a coveted Mini Kelly bag for her daughter North West and was rejected simply never happened.

We’re told Kim has maintained a very friendly relationship with the luxury brand for years but not through the channels described in the report.

According to our sources, Kim has a very friendly relationship with the brand and has only used the same contact for over ten years in Paris and not the press office.

The sources also shut down the central claim behind the rumor telling us Kim did not request a bag for North, nor did she visit any Hermes store recently or get turned down.

We’re told those close to the situation are particularly bothered by the story because it involves a child. One source said, “They find it very disturbing that anyone would make up stories about a child for clicks.”

The claim appears in journalist Amy Odell’s “Back Row” newsletter, which cited a former employee of the Beverly Hills Hermès boutique who alleged Kim and Kanye West once tried to purchase a black Mini Kelly bag for North but were denied.

The ultra-rare alligator Mini Kelly is one of the most coveted Hermès bags on the market and can fetch more than $75,000 on resale.

Lifestyle

This historian dug up the hidden history of ‘amateur’ blackface in America

In 2013, historian Rhae Lynn Barnes was researching blackface in America when she encountered a stumbling block at the Library of Congress: Various primary sources on the subject were listed as “missing on shelf.”

Barnes spoke to one of the librarians, and explained that she was writing a history of minstrel shows and white supremacy. Barnes says the librarian admitted that, in 1987, she had personally hidden some of these books because she feared the material would be used by the Ku Klux Klan.

“Once [the librarian] understood the research I was doing … a few hours later, she came up with a cart packed to the brim with all of the material that I had been hoping to see,” Barnes says.

In her new book Darkology: Blackface and the American Way of Entertainment, Barnes traces the origin of minstrel shows, performances in which an actor portrays an exaggerated and racist depiction of Black, often formerly enslaved, people.

Barnes says minstrel became so popular in the 1800s that the stars began publishing “step-by-step guides” explaining how amateurs could create their own shows. By the end of the century, amateur minstrel performances became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the U.S. Many groups, including fraternal orders, PTAs, police and firemen’s associations and soldiers on military bases, put on their own shows.

During the Great Depression, Barnes notes that President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration sought to “preserve American heritage” by promoting blackface. As part of the effort, she says, the government distributed lists of “top minstrel plays that they recommended to schools, to local charities, to colleges.” Roosevelt was such a fan of minstrel shows that he co-wrote a script, to be performed by children with polio.

Barnes credits the civil rights era and especially mothers with helping de-popularize blackface in the 1970s, first in schools and then in the larger culture. “They successfully get the shows out of school curriculum piece by piece. And by 1970, most of these publishing houses are going under because of the incredible work of Black and white mothers who worked with them,” she says.

Interview highlights

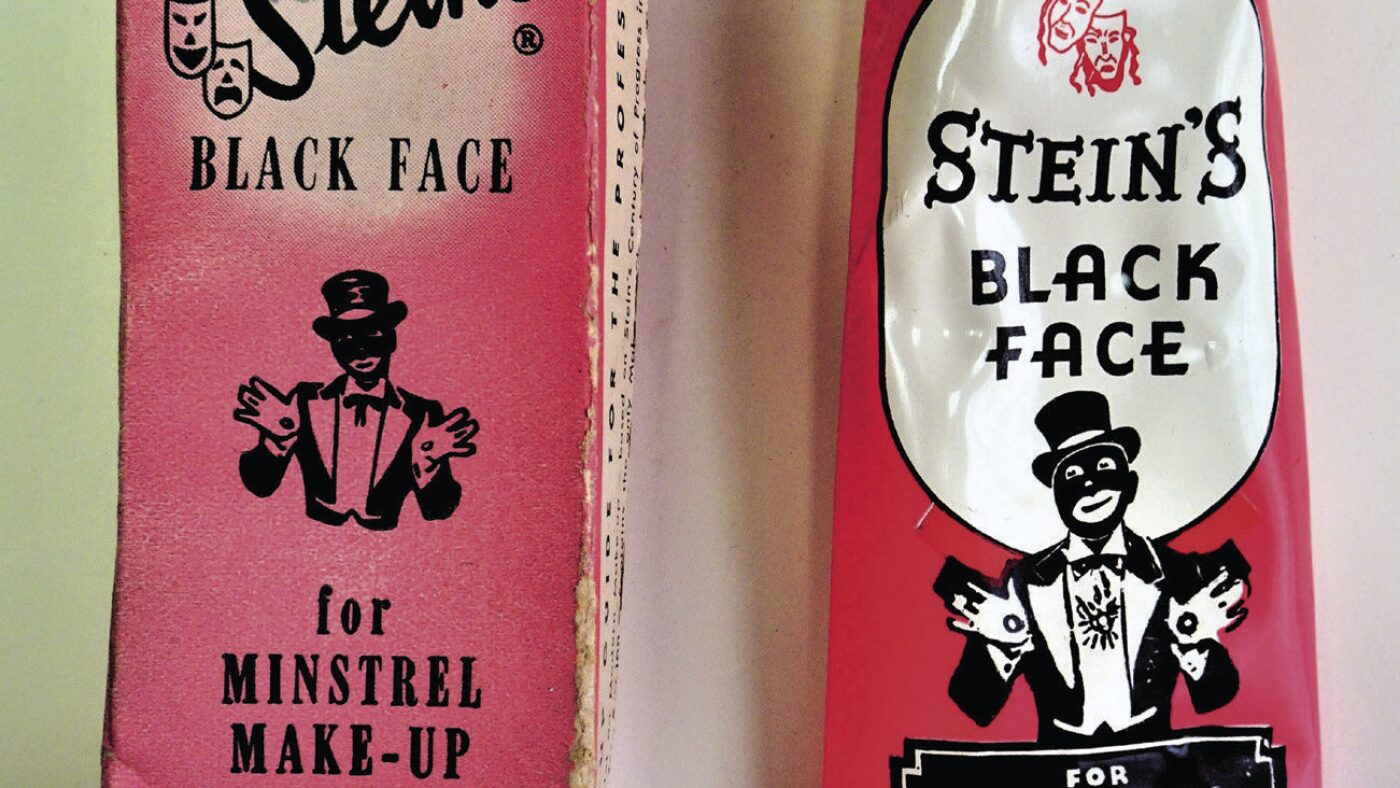

Stein’s makeup company created multiple shades of blackface for performers in amateur minstrel shows.

WW Norton

hide caption

toggle caption

WW Norton

On commercial blackface makeup that replaced shoe polish and burnt cork

It’s an entire commercial empire. So Stein’s makeup was one of the largest. They were a theatrical makeup company. And you’ll actually find today when you go into Halloween stores that a lot of these blackface makeup companies still exist today for Halloween costume makeup and also for clown makeup. …

Burnt cork was incredibly difficult to get off of your face. You’re essentially taking fire ash and then mixing it with shoe polish or some sort of shiny ingredients, and so it was incredibly hard to get it off. So when Stein and these other cosmetic companies begin to create the tubes … that did come in 29 colors and you could pick which bizarre racial calculus you wanted to represent, they would come off with cold cream or makeup remover and that was one of their selling points — now it’s easy to take off.

On Stephen Foster‘s songs for minstrel shows, like “Oh Susannah!”

What’s interesting about those songs is they are romanticizing the relationship between an enslaved person and their enslaver. And so when we have commentary, even from the president now, who recently said slavery wasn’t so bad, well, slavery was horrific, but if you were raised on a diet of Stephen Foster music, and going to minstrel shows, you can somewhat understand how somebody at the time could easily be led to believe that slavery was a grand old party because that’s what it was supposed to be telling you. It’s pro-slavery propaganda.

On the slogan “Make America Great Again” originating from early 20th-century minstrel shows

“Make America Great Again” or “This Is Our Country” or “Take Back Our Country” are all slogans and songs that were very common in minstrel shows. And so a lot of minstrel shows reinterpreted slavery in a fantastical way, that the Civil War ended and that in these minstrel shows there was Black rule and that everything America held dear was desecrated. And so this [blackface] “Zip” character … sometimes he’s named “Rastus” — he has different names that he goes by — runs for office, political office, becomes president, and he’s the first Black president and the first thing he does is he takes away America’s guns. Sound familiar? And so a lot of these terms that you could perhaps say [are] dog whistles in white of supremacy are taken line for line from these minstrel shows.

On not censoring this history

Historians right now are in somewhat of a culture war in that it is our patriotic duty as American citizens and as patriots to help make sure that the American public has access to our history in all of its complexity. And the truth is that you can’t understand the victories and the triumphs without understanding how far Americans had to push. And I think that’s especially true of blackface. When we didn’t adequately understand how long blackface was a mainstay in American culture. Because many historians believe that it had died out by 1900, when in fact it only accelerates and increases up through the 1970s. And so if you just say, “Oh, it just died out. It was no longer in fashion,” then what you’re losing is the incredible, dangerous, and brave work of thousands of Black and white mothers across the United States in the 1950s and the 1960s, of students who stood up during Jim Crow America and said, “This is not OK. We are humans. We deserve dignity. And we want you to understand our history.” …

I think these are the hard conversations Americans actually want to have. And I think America is completely ready for those hard conversations and moving forward.

Anna Bauman and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts7 days ago

Massachusetts7 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Pennsylvania5 days ago

Pennsylvania5 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago2 Survivors Describe the Terror and Tragedy of the Tahoe Avalanche

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Virginia6 days ago

Virginia6 days agoGiants will hold 2026 training camp in West Virginia