Alaska

On the Yukon, Alaska and Canada are bound together by salmon – and their collapse

The Yukon River covers a lot of ground on its nearly 2,000 mile journey to the sea. The river’s headwaters are in the mountains of northern British Columbia, just 50 miles from Skagway. From there, the river winds north through the Yukon, crosses the border near Eagle and flows all the way across Interior Alaska until it finally reaches the Bering Sea.

And for as long as anyone can remember, salmon fed everyone along its course.

“For most of our lives, it was king salmon,” said Rhonda Pitka, First Chief of the village of Beaver in the upper Yukon Flats. “That was the majority of our diet, and what we traded and what we processed.”

Pitka remembers busy childhood summers with her family at their fish camp about ten miles outside the village, helping her grandmother catch and process fish.

But today, she can’t continue that tradition with her own family.

Since the mid-1990’s, runs of king and chum salmon — the two primary species harvested on the Yukon River — have become more unpredictable. King salmon numbers have seen a long, slow decline, while chum runs have sometimes seemed to bounce back, only to fall again. Now, both species are in a historic collapse.

In the last four years, the numbers of king and chum salmon in the river have dropped so low, state and federal fisheries managers have all but closed subsistence fishing. The causes of the decline aren’t fully understood, but researchers say a parasite targeting kings and warming waters due to human-caused climate change are possible factors. Harvesters also blame salmon bycatch in the Bering Sea commercial pollock fishery and the large commercial chum salmon fishery off the Alaska Peninsula known as “Area M.”

The closures have been devastating for communities along the river, said Pitka, who remembers trading salmon for caribou or muktuk with relatives in Arctic Village and Utqiaġvik back when fish were abundant.

“It’s been a real challenge for families to get enough food for the winter and enough food to share,” Pitka said.

The salmon collapse is changing life on the Yukon — and not just in Alaska.

Communities along the upper Yukon, stretching deep into Canada, have borne the brunt of the salmon collapse, in part because only a fraction of the fish make it that far upriver. Some Canadian First Nations have restricted fishing for decades.

Still, the U.S. and Canada depend upon each other to conserve this vital resource.

Pitka serves on the Yukon River Panel, a body of representatives from both Alaska and Canada that advises fishery managers on both sides of the border. The panel was established by the landmark Yukon River Salmon Agreement, a treaty the U.S. and Canada signed in the early 2000s after more than a decade of negotiations. The treaty aims to ensure a healthy salmon population and access to fishing for communities in both countries.

It’s been a challenge to discuss resource allocation for a river that’s not actually meeting anyone’s subsistence needs, Pitka said.

“Our Canadian counterparts haven’t fished for at least 20 years, if not longer,” Pitka said. “And that’s a tragedy all in itself. It’s been really difficult. It’s been really tense.”

As part of that agreement, Alaska committed to letting a certain number of fish cross into Canada, said John Linderman, the panel’s U.S. co-chair.

“Each country has its own responsibilities under the treaty agreement,” Linderman said. “For Alaska, one of our most important responsibilities is to annually provide to the Canadian border the escapement goal and the Canadian harvest share.”

That means allowing enough fish to make it back to their spawning grounds to ensure a healthy salmon population and, in better years, ensuring an additional number of fish cross the border to allow a fair harvest up and down the river.

Those requirements can sometimes sound like a burden for Alaskans, said Holly Carroll, the Alaska subsistence fisheries manager for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service – especially during the last four years, when managers have heavily restricted subsistence fishing. But, she said, that’s the wrong way to look at it.

“People will say, ‘Just let us fish. I don’t take more than I need, my family does not take more than I need.’ And every family will tell you that, and they mean it and they are honest,” Carroll said. “But here’s the problem: when our runs are too small to meet everyone’s needs, we have to close.”

Lately, there aren’t even enough salmon returning to the river to ensure healthy runs in the future. And that means everyone on the river — Alaskan and Canadian — has had to sacrifice.

The treaty keeps both sides working together to protect their salmon. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy, Pitka said.

She recalled a potlatch after two recent deaths in Stevens Village, near her village of Beaver. It was painful to hold such a gathering without its traditional center.

“It was so hard to see families not have salmon to give out at potlatch,” Pitka said. “There should have been salmon on everybody’s plate. They should have been able to give salmon out to visitors that were leaving.”

“That’s the cultural connection that we’re missing right now,” she said. “The ability to share and to feed our families our cultural foods.”

Alaska

Federal funds will help DOT study wildlife crashes on Glenn Highway

New federal funds will help Alaska’s Department of Transportation develop a plan to reduce vehicle collisions with wildlife on one of the state’s busiest highways.

The U.S. Transportation Department gave the state a $626,659 grant in December to conduct a wildlife-vehicle collision study along the Glenn Highway corridor stretching between Anchorage’s Airport Heights neighborhood to the Glenn-Parks Highway interchange.

Over 30,000 residents drive the highway each way daily.

Mark Eisenman, the Anchorage area planner for the department, hopes the study will help generate new ideas to reduce wildlife crashes on the Glenn Highway.

“That’s one of the things we’re hoping to get out of this is to also have the study look at what’s been done, not just nationwide, but maybe worldwide,” Eisenman said. “Maybe where the best spot for a wildlife crossing would be, or is a wildlife crossing even the right mitigation strategy for these crashes?”

Eisenman said the most common wildlife collisions are with moose. There were nine fatal moose-vehicle crashes on the highway between 2018 and 2023. DOT estimates Alaska experiences about 765 animal-vehicle collisions annually.

In the late 1980s, DOT lengthened and raised a downtown Anchorage bridge to allow moose and wildlife to pass underneath, instead of on the roadway. But Eisenman said it wasn’t built tall enough for the moose to comfortably pass through, so many avoid it.

DOT also installed fencing along high-risk areas of the highway in an effort to prevent moose from traveling onto the highway.

Moose typically die in collisions, he said, and can also cause significant damage to vehicles. There are several signs along the Glenn Highway that tally fatal moose collisions, and he said they’re the primary signal to drivers to watch for wildlife.

“The big thing is, the Glenn Highway is 65 (miles per hour) for most of that stretch, and reaction time to stop when you’re going that fast for an animal jumping onto the road is almost impossible to avoid,” he said.

The city estimates 1,600 moose live in the Anchorage Bowl.

Alaska

Flight attendant sacked for twerking on the job: ‘What’s wrong with a little twerk before work’

They deemed the stunt not-safe-for-twerk.

An Alaska Airlines flight attendant who was sacked for twerking on camera has created a GoFundMe to support her while she seeks a new berth.

The crewmember, named Nelle Diala, had filmed the viral booty-shaking TikTok video on the plane while waiting two hours for the captain to arrive, A View From the Wing reported.

She captioned the clip, which also blew up on Instagram, “ghetto bih till i D-I-E, don’t let the uniform fool you.”

Diala was reportedly doing a victory dance to celebrate the end of her new hire probationary period.

Unfortunately, her jubilation was short-lived as Alaska Airlines nipped her employment in the bum just six months into her contract.

The fanny-wagging flight attendant feels that she didn’t do anything wrong.

Diala has since reposted the twerking clip with the new caption: “Can’t even be yourself anymore, without the world being so sensitive. What’s wrong with a little twerk before work, people act like they never did that before.”

The new footage was hashtagged #discriminationisreal.

The disgraced stewardess even set up a GoFundMe page to help support the so-called “wrongfully fired” flight attendant until she can land a new flight attendant gig.

“I never thought a single moment would cost me everything,” wrote the ex-crewmember. “Losing my job was devastating.”

She claimed that the gig had allowed her to meet new people and see the world, among other perks.

While air hostessing was ostensibly a “dream job,” Diala admitted that she used the income to help fund her “blossoming lingerie and dessert businesses,” which she runs under the Instagram handles @cakezncake (which doesn’t appear to have any content?) and @figure8.lingerie.

As of Wednesday morning, the crowdfunding campaign has raised just $182 of its $12,000 goal.

Diala was ripped online for twerking on the job as well as her subsequent GoFundMe efforts.

“You don’t respect the uniform, you don’t respect your job then,” declared one critic on the popular aviation-focused Instagram page The Crew Lounge. “Terms and Conditions apply.”

“‘Support for wrongly fired flight attendant??’” mocked another. “Her GoFund title says it all. She still thinks she was wrongly fired. Girl you weren’t wrongly fired. Go apply for a new job and probably stop twerking in your uniform.”

“The fact that you don’t respect your job is one thing but doing it while in uniform and at work speaks volumes,” scoffed a third. “You’re the brand ambassador and it’s not a good look.”

Alaska

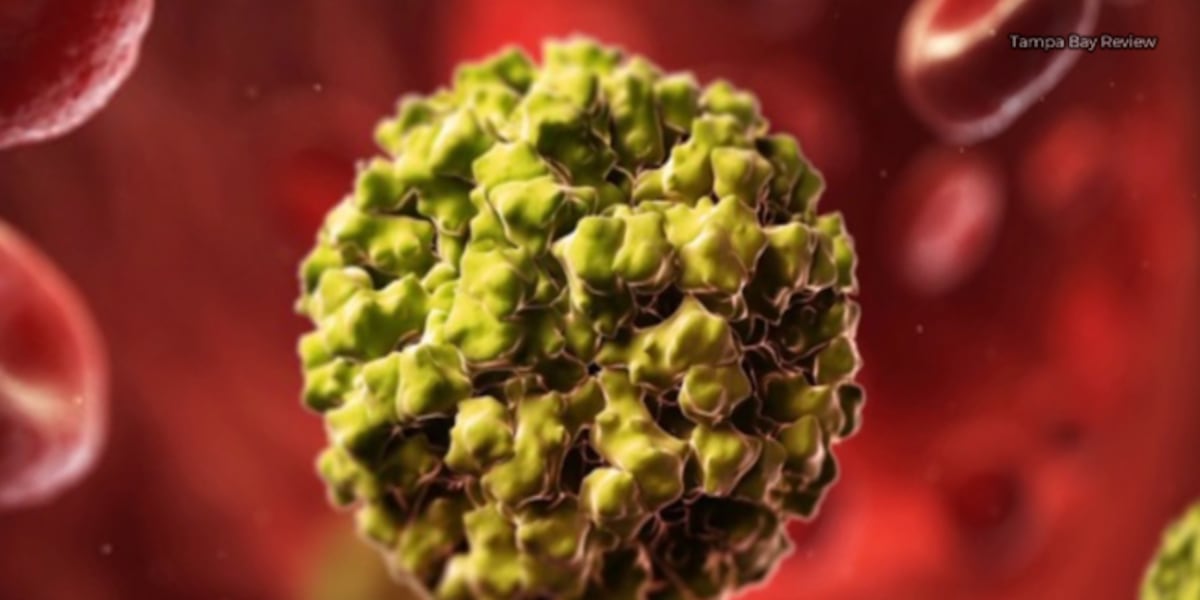

As Alaska sees a spike in Flu cases — another virus is on the rise in the U.S.

FAIRBANKS, Alaska (KTUU) – Alaska has recently seen a rise in both influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, better known as RSV. Amidst the spike in both illnesses, norovirus has also been on the rise in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says it’s highly contagious and hand sanitizers don’t work well against it.

Current data for Alaska shows 449 influenza cases and 262 RSV cases for the week of Jan. 4. Influenza predominantly impacts the Kenai area, the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, and the Northwest regions of the state. RSV is also seeing significant activity in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and Anchorage.

Both are respiratory viruses that are treatable, but norovirus — which behaves like the stomach flu according to the CDC — is seeing a surge at the national level. It “causes acute gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach or intestines,” as stated on the CDC webpage.

This virus is spread through close contact with infected people and surfaces, particularly food.

“Basically any place that people aggregate in close quarters, they’re going to be especially at risk,” said Dr. Sanjay Gupta, CNN’s Chief Medical Correspondent.

Preventing infection is possible but does require diligence. Just using hand sanitizer “does not work well against norovirus,” according to the CDC. Instead, the CDC advises washing your hands with soap and hot water for at least 20 seconds. When preparing food or cleaning fabrics — the virus “can survive temperatures as high as 145°F,” as stated by the CDC.

According to Dr. Gupta, its proteins make it difficult to kill, leaving many cleaning methods ineffective. To ensure a given product can kill the virus, he advises checking the label to see if it claims it can kill norovirus. Gupta said you can also make your own “by mixing bleach with water, 3/4 of a cup of bleach per gallon of water.”

For fabrics, it’s best to clean with water temperatures set to hot or steam cleaning at 175°F for five minutes.

As for foods, it’s best to throw out any items that might have norovirus. As a protective measure, it’s best to cook oysters and shellfish to a temperature greater than 145°F.

Based on Alaska Department of Health data, reported COVID-19 cases are significantly lower than this time last year.

See a spelling or grammatical error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2025 KTVF. All rights reserved.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

Science4 days ago

Science4 days agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLas Vegas police release ChatGPT logs from the suspect in the Cybertruck explosion

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoMichael J. Fox honored with Presidential Medal of Freedom for Parkinson’s research efforts

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: Millennials try to buy-in or opt-out of the “American Meltdown”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPhotos: Pacific Palisades Wildfire Engulfs Homes in an L.A. Neighborhood

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrial Starts for Nicolas Sarkozy in Libya Election Case