Science

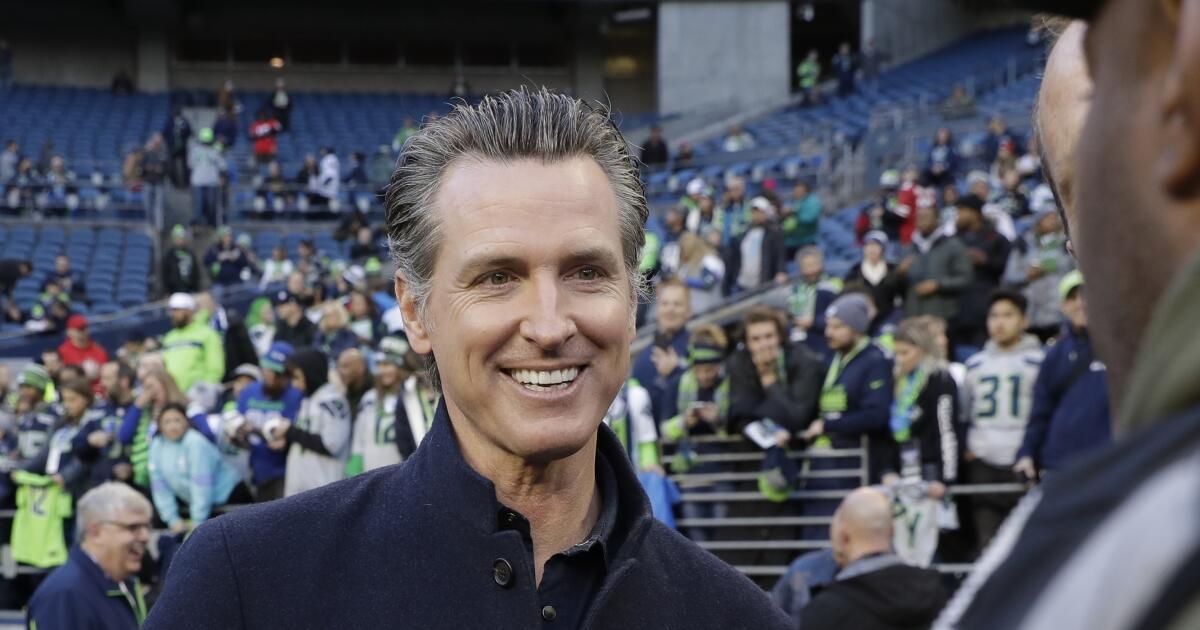

Newsom blocks proposed ban on youth tackle football: 'Parents have the freedom to decide'

Gov. Gavin Newsom pledged Wednesday to hold the line against a proposed law that would ban youth tackle football in California, saying in a statement to The Times that he’d veto any such legislation.

Assembly Bill 734 was introduced last year by state Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento) and cleared its first hurdle a week ago when a legislative committee voted 5 to 2 along party lines for the measure to be considered by the 80-member Assembly.

Originally written to prohibit children under age 12 from playing tackle football, the bill was amended in committee to ban the sport for children 5 or younger beginning in 2025. In 2027, the bill would raise the age on the ban to 9, and in 2029 it would go to 11.

California’s Democratic governor, however, wants no part of a bill that would dictate to parents the age they can allow their children to participate in a sport.

“I will not sign legislation that bans youth tackle football,” Newsom said in the statement. “I am deeply concerned about the health and safety of our young athletes, but an outright ban is not the answer.

“My Administration will work with the Legislature and the bill’s author to strengthen safety in youth football — while ensuring parents have the freedom to decide which sports are most appropriate for their children.”

Studies of the effects of blows to the head from playing tackle football are mixed. A 2016 study published by the Radiological Society of North America found that a single season of tackle football can affect the brains of players as young as 8. Researchers concluded that even hits that did not lead to a diagnosed concussion produced adverse effects.

The degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is tied to concussions and brain trauma but cannot be diagnosed until a person is deceased and their brain can be studied. Boston University researchers found that among 211 football players diagnosed with CTE after death, those who began tackle football before age 12 had an earlier onset of cognitive, behavior, and mood symptoms by an average of 13 years.

Every one year younger that the individuals began to play tackle football predicted an earlier onset of cognitive problems by 2.4 years and behavioral and mood problems by 2½ years, researchers found.

“Youth exposure to repetitive head impacts in tackle football may reduce one’s resiliency to brain diseases later in life, including, but not limited to CTE,” said Ann McKee, director of the Boston University CTE Center. “It makes common sense that children, whose brains are rapidly developing, should not be hitting their heads hundreds of times per season.”

However, a 2019 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. that tracked tackle football players ages 9 to 12 over four seasons found that repeated blows to the head were not associated with cognitive or behavioral problems. Neurocognitive performance instead is tied to medical diagnoses such as anxiety, depression and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

No state has banned tackle football for kids, but there have been attempts to do so. Similar bills introduced previously in California, New York, Illinois, Massachusetts and Maryland failed to pass.

McCarty’s proposed law comes on the heels of the 2021 California Youth Football Act (CYFA), which requires tackle football coaches to complete concussion and head-injury education and for parents of young participants to receive similar information. The act also requires youth tackle football leagues to assist in tracking youth sports injuries.

Opponents of the proposed law say that it is premature, that implementing and studying the effectiveness of the CYFA needs time. Newsom seemed to side with that point of view in his statement.

“California remains committed to building on the California Youth Football Act, which I signed in 2019, establishing advanced safety standards for youth football,” he said. “This law provides a comprehensive safety framework for young athletes, including equipment standards and restrictions on exposure to full-contact tackles.”

Proponents of tackle football along with groups that advocate for less government intrusion have been vociferous in their objection to the proposed law. The California Youth Football Alliance posted on Facebook to “Huddle up California,” urging members to “protect parental rights, stand up to big government, and separate fact from fiction.”

In a 2023 Washington Post poll of 1,006 adults, 75% of those who identified as conservatives said they would recommend youth or high school football to kids compared with only 44% of liberals. This was a change from a 2012 Post poll in which the conservative-liberal gap was only 70% to 63%.

McCarty said keeping children from playing tackle football until they reach adolescence is simply common sense.

“There are other alternatives for young kids, other sports, other football activities like flag football — which the NFL is heavily investing in,” he said. “There is a way to love football and protect our kids. We’ve come to realize that there is no real safe way to play youth tackle football. There is no safe blow to the head for 6-, 7- and 8-year-olds and they should not be experiencing hundreds of sub-concussive hits to the head on an annual basis when there is an alternative.”

Still, Newsom would have veto power even if the bill made it through the full Assembly and Senate, and he made it clear he’d use it.

“We will consult with health and sports medicine experts, coaches, parents, and community members to ensure California maintains the highest standards in the country for youth football safety,” he said in his statement. “We owe that to the legions of families in California who have embraced youth sports.”

Science

In search for autism’s causes, look at genes, not vaccines, researchers say

Earlier this year, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. pledged that the search for autism’s cause — a question that has kept researchers busy for the better part of six decades — would be over in just five months.

“By September, we will know what has caused the autism epidemic, and we’ll be able to eliminate those exposures,” Kennedy told President Trump during a Cabinet meeting in April.

That ambitious deadline has come and gone. But researchers and advocates say that Kennedy’s continued fixation on autism’s origins — and his frequent, inaccurate claims that childhood vaccines are somehow involved — is built on fundamental misunderstandings of the complex neurodevelopmental condition.

Even after more than half a century of research, no one yet knows exactly why some people have autistic traits and others do not, or why autism spectrum disorder looks so different across the people who have it. But a few key themes have emerged.

Researchers believe that autism is most likely the result of a complex set of interactions between genes and the environment that unfold while a child is in the womb. It can be passed down through families, or originate with a spontaneous gene mutation.

Environmental influences may indeed play a role in some autism cases, but their effect is heavily influenced by a person’s genes. There is no evidence for a single trigger that causes autism, and certainly not one a child encounters after birth: not a vaccine, a parenting style or a post-circumcision Tylenol.

“The real reason why it’s complicated, the more fundamental one, is that there’s not a single cause,” said Irva Hertz-Picciotto, a professor of public health science and director of the Environmental Health Sciences Center at UC Davis. “It’s not a single cause from one person to the next, and not a single cause within any one person.”

Kennedy, an attorney who has no medical or scientific training, has called research into autism’s genetics a “dead end.” Autism researchers counter that it’s the only logical place to start.

“If we know nothing else, we know that autism is primarily genetic,” said Joe Buxbaum, a molecular neuroscientist who directs the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “And you don’t have to actually have the exact genes [identified] to know that something is genetic.”

Some neurodevelopment disorders arise from a difference in a single gene or chromosome. People with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21, for example, and Fragile X syndrome results when the FMR1 gene isn’t expressed.

Autism in most cases is polygenetic, which means that multiple genes are involved, with each contributing a little bit to the overall picture.

Researchers have found hundreds of genes that could be associated with autism; there may be many more among the roughly 20,000 in the human genome.

In the meantime, the strongest evidence that autism is genetic comes from studies of twins and other sibling groups, Buxbaum and other researchers said.

The rate of autism in the U.S. general population is about 2.8%, according to a study published last year in the journal Pediatrics. Among children with at least one autistic sibling, it’s 20.2% — about seven times higher than the general population, the study found.

Twin studies reinforce the point. Both identical and fraternal twins develop in the same womb and are usually raised in similar circumstances in the same household. The difference is genetic: identical twins share 100% of their genetic information, while fraternal twins share about 50% (the same as nontwin siblings).

If one fraternal twin is autistic, the chance that the other twin is also autistic is about 20%, or about the same as it would be for a nontwin sibling.

But if one in a pair of identical twins is autistic, the chance that the other twin is also autistic is significantly higher. Studies have pegged the identical twin concurrence rate anywhere from 60% to 90%, though the intensity of the twins’ autistic traits may differ significantly.

Molecular genetic studies, which look at the genetic information shared between siblings and other blood relatives, have found similar rates of genetic influence on autism, said Dr. John Constantino, a professor of pediatrics, psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Emory University School of Medicine and chief of behavioral and mental health at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Together, he said, “those studies have indicated that a vast share of the causation of autism can be traced to the effects of genetic influences. That is a fact.”

Buxbaum compares the heritability of autism to the heritability of height, another polygenic trait.

“There’s not one gene that’s making you taller or shorter,” Buxbaum said. Hundreds of genes play a role in where you land on the height distribution curve. A lot of those genes run in families — it’s not unusual for very tall people, for example, to have very tall relatives.

But parents pass on a random mix of their genes to their children, and height distribution across a group of same-sex siblings can vary widely. Genetic mutations can change the picture. Marfan syndrome, a condition caused by mutations in the FBN1 gene, typically makes people grow taller than average. Hundreds of genetic mutations are associated with dwarfism, which causes shorter stature.

Then once a child is born, external factors such as malnutrition or disease can affect the likelihood that they reach their full height potential.

So genes are important. But the environment — which in developmental science means pretty much anything that isn’t genetics, including parental age, nutrition, air pollution and viruses — can play a major role in how those genes are expressed.

“Genetics does not operate in a vacuum, and at the same time, the impact of the environment on people is going to depend on a person’s individual genetics,” said Brian K. Lee, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University who studies the genetics of developmental disorders.

Unlike the childhood circumstances that can affect height, the environmental exposures associated with autism for the most part take place in utero.

Researchers have identified multiple factors linked to increased risks of the disorder, including older parental age, infant prematurity and parental exposure to air pollution and industrial solvents.

Investigations into some of these linkages were among the more than 50 autism-related studies whose funding Kennedy has cut since taking office, a ProPublica investigation found. In contrast, no credible study has found links between vaccines and autism — and there have been many.

One move from the Department of Health and Human Services has been met with cautious optimism: even as Kennedy slashed funding to other research projects, the department in September announced a $50-million initiative to explore the interactions of genes and environmental factors in autism, which has been divided among 13 different research groups at U.S. universities, including UCLA and UC San Diego.

The department’s selection of well-established, legitimate research teams was met with relief by many autism scientists.

But many say they fear that such decisions will be an anomaly under Kennedy, who has repeatedly rejected facts that don’t conform to his preferred hypotheses, elevated shoddy science and muddied public health messaging on autism with inaccurate information.

Disagreements are an essential part of scientific inquiry. But the productive ones take place in a universe of shared facts and build on established evidence.

And when determining how to spend limited resources, researchers say, making evidence-based decisions is vital.

“There are two aspects of these decisions: Is it a reasonable expenditure based on what we already know? And if you spend money here, will you be taking money away from HHS that people are in desperate need of?” Constantino said. “If you’re going to be spending money, you want to do that in a way that is not discarding what we already know.”

Science

Contributor: New mothers are tempted by Ozempic but don’t have the data they need

My friend Sara, eight weeks after giving birth, left me a tearful voicemail. I’m a clinical psychologist specializing in postpartum depression and psychosis, but mental health wasn’t Sara’s issue. Postpartum weight gain was.

Sara told me she needed help. She’d gained 40 pounds during her pregnancy, and she was still 25 pounds overweight. “I’m going back to work and I can’t look like this,” she said. “I need to take Ozempic or something. But do you know if it’s safe?”

Great question. Unfortunately researchers don’t yet have an answer. On Dec. 1, the World Health Organization released its first guidelines on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists such as Ozempic, generically known as semaglutide. One of the notable policy suggestions in that report is to not prescribe GLP-1s to pregnant women. Disappointingly, the report says nothing about the use of the drug by postpartum women, including those who are breastfeeding.

There was a recent Danish study that led to medical guidelines against prescribing to patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

None of that is what my friend wanted to hear. I could only encourage her to speak to her own medical doctor.

Sara’s not alone. I’ve seen a trend emerging in my practice in which women use GLP-1s to shed postpartum weight. The warp speed “bounce-back” ideal of body shapes for new mothers has reemerged, despite the mental health field’s advocacy to abolish the archaic pressure of martyrdom in motherhood. GLP-1s are being sold and distributed by compound pharmacies like candy. And judging by their popularity, nothing tastes sweeter than skinny feels.

New motherhood can be a stressful time for bodies and minds, but nature has also set us up for incredible growth at that moment. Contrary to the myth of spaced-out “mommy brains,” new neuroplasticity research shows that maternal brains are rewired for immense creativity and problem solving.

How could GLP-1s affect that dynamic? We just don’t know. We do know that these drugs are associated with changes far beyond weight loss, potentially including psychiatric effects such as combating addiction.

Aside from physical effects, this points to an important unanswered research question: What effects, if any, do GLP-1s have on a woman’s brain as it is rewiring to attune to and take care of a newborn? And on a breastfeeding infant? If GLP-1s work on the pleasure center of the brain and your brain is rewiring to feel immense pleasure from a baby coo, I can’t help but wonder if that will be dampened. When a new mom wants a prescription for a GLP-1 to help shed baby weight, her medical provider should emphasize those unknowns.

These drugs may someday be a useful tool for new mothers. GLP-1s are helping many people with conditions other than obesity. A colleague of mine was born with high blood pressure and cholesterol. She exercised every day and adopted a pescatarian diet. Nothing budged until she added a GLP-1 to her regimen, bringing her blood pressure to a healthy 120/80 and getting cholesterol under control. My brother, an otherwise healthy young man recently diagnosed with a rare idiopathic lymphedema of his left leg, is considering GLP-1s to address inflammation and could be given another chance at improving his quality of life.

I hope that GLP-1s will continue to help those who need it. And I urge everyone — especially new moms — to proceed with caution. A healthy appetite for nutritious food is natural. That food fuels us for walks with our dogs, swims along a coastline, climbs through leafy woods. It models health and balance for the young ones who are watching us for clues about how to live a healthy life.

Nicole Amoyal Pensak, a clinical psychologist and researcher, is the author of “Rattled: How to Calm New Mom Anxiety With the Power of the Postpartum Brain.”

Science

California issues advisory on a parasitic fly whose maggots can infest living humans

A parasitic fly whose maggots can infest living livestock, birds, pets and humans could threaten California soon.

The New World Screwworm has rapidly spread northward from Panama since 2023 and farther into Central America. As of early September, the parasitic fly was present in seven states in southern Mexico, where 720 humans have been infested and six of them have died. More than 111,000 animals also have been infested, health officials said.

In early August, a person traveling from El Salvador to Maryland was discovered to have been infested, federal officials said. But the parasitic fly has not been found in the wild within a 20-mile radius of the infested person, which includes Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

After the Maryland incident, the California Department of Public Health decided to issue a health advisory this month warning that the New World Screwworm could arrive in California from an infested traveler or animal, or from the natural travel of the flies.

Graphic images of New World Screwworm infestations show open wounds in cows, deer, pigs, chickens, horses and goats, infesting a wide swath of the body from the neck, head and mouth to the belly and legs.

The Latin species name of the fly — hominivorax — loosely translates to “maneater.”

“People have to be aware of it,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious diseases specialist. “As the New World Screwworm flies northward, they may start to see people at the borders — through the cattle industry — get them, too.”

Other people at higher risk include those living in rural areas where there’s an outbreak, anyone with open sores or wounds, those who are immunocompromised, the very young and very old, and people who are malnourished, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

There could be grave economic consequences should the New World Screwworm get out of hand among U.S. livestock, leading to animal deaths, decreased livestock production, and decreased availability of manure and draught animals, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“It is not only a threat to our ranching community — but it is a threat to our food supply and our national security,” the USDA said.

Already, in May, the USDA suspended imports of live cattle, horse and bison from the Mexican border because of the parasitic fly’s spread through southern Mexico.

The New World Screwworm isn’t new to the U.S.

But it was considered eradicated in the United States in 1966, and by 1996, the economic benefit of that eradication was estimated at nearly $800 million, “with an estimated $2.8 billion benefit to the wider economy,” the USDA said.

Texas suffered an outbreak in 1976. A repeat could cost the state’s livestock producers $732 million a year and the state economy $1.8 billion, the USDA said.

Historically, the New World Screwworm was a problem in the U.S. Southwest and expanded to the Southeast in the 1930s after a shipment of infested animals, the USDA said. Scientists in the 1950s discovered a technique that uses radiation to sterilize male parasitic flies.

Female flies that mate with the sterile male flies produce sterile eggs, “so they can’t propagate anymore,” Chin-Hong said. It was this technique that allowed the U.S., Mexico and Central America to eradicate the New World Screwworm by the 1960s.

But the parasitic fly has remained endemic in South America, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

In late August, the USDA said it would invest in new technology to try to accelerate the pace of sterile fly production. The agency also said it would build a sterile-fly production facility at Edinburg, Texas, which is close to the Mexico border, and would be able to produce up to 300 million sterile flies per week.

“This will be the only United States-based sterile fly facility and will work in tandem with facilities in Panama and Mexico to help eradicate the pest and protect American agriculture,” the USDA said.

The USDA is already releasing sterile flies in southern Mexico and Central America.

The risk to humans from the fly, particularly in the U.S., is relatively low. “We have decent nutrition; people have access to medical care,” Chin-Hong said.

But infestations can happen. Open wounds are a danger, and mucus membranes can also be infested, such as inside the nose, according to the CDC.

An infestation occurs when fly maggots infest the living flesh of warm-blooded animals, the CDC says. The flies “land on the eyes or the nose or the mouth,” Chin-Hong said, or, according to the CDC, in an opening such as the genitals or a wound as small as an insect bite. A single female fly can lay 200 to 300 eggs at a time.

When they hatch, the maggots — which are called screwworms — “have these little sharp teeth or hooks in their mouths, and they chomp away at the flesh and burrow,” Chin-Hong said. After feeding for about seven days, a maggot will fall to the ground, dig into the soil and then awaken as an adult fly.

Deaths among humans are uncommon but can happen, Chin-Hong said. Infestation should be treated as soon as possible. Symptoms can include painful skin sores or wounds that may not heal, the feeling of the larvae moving, or a foul-smelling odor, the CDC says.

Patients are treated by removal of the maggots, which need to be killed by putting them into a sealed container of concentrated ethyl or isopropyl alcohol then disposed of as biohazardous waste.

The parasitic fly has been found recently in seven Mexican states: Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatán. Officials urge travelers to keep open wounds clean and covered, avoid insect bites, and wear hats, loose-fitting long-sleeved shirts and pants, socks, and insect repellents registered by the Environmental Protection Agency as effective.

-

Alaska5 days ago

Alaska5 days agoHowling Mat-Su winds leave thousands without power

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump rips Somali community as federal agents reportedly eye Minnesota enforcement sweep

-

Ohio1 week ago

Who do the Ohio State Buckeyes hire as the next offensive coordinator?

-

Texas6 days ago

Texas6 days agoTexas Tech football vs BYU live updates, start time, TV channel for Big 12 title

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump threatens strikes on any country he claims makes drugs for US

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHonduras election council member accuses colleague of ‘intimidation’

-

Washington3 days ago

Washington3 days agoLIVE UPDATES: Mudslide, road closures across Western Washington

-

Iowa4 days ago

Iowa4 days agoMatt Campbell reportedly bringing longtime Iowa State staffer to Penn State as 1st hire