Science

James Watson, Nobel Prize winner and DNA pioneer, dies

On a chilly February afternoon in 1953, a gangly American and a fast-talking Brit walked into the Eagle pub in Cambridge, England, and announced to the assembled imbibers that they had discovered the “secret of life.”

Even by the grandiose standards of bar talk, it was a provocative statement. Except, it was also pretty close to the truth. That morning, James Watson, the American whiz kid who had not yet turned 25, and his British colleague, Francis Crick, had finally worked out the structure of DNA.

Everything that followed, unlocking the human genome, learning to edit and move genetic information to cure disease and create new forms of life, the revolution in criminal justice with DNA fingerprinting, and many other things besides, grew out of the discovery of the double-helix shape of DNA.

It took Watson decades to feel worthy of a breakthrough some consider the equal of Einstein’s famous E=MC2 formula. But he got there. “Did Francis and I deserve the double helix?” Watson asked rhetorically, 40 years later. “Yeah, we did.”

James Dewey Watson, Nobel Prize winner and “semi-professional loose cannon” whose racist views made him a scientific pariah late in life, died Thursday in hospice care in New York after a brief illness, according to officials at his former laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. He was 97.

Born April 6, 1928, in Chicago, he was the son of a bill collector for a mail-order school who had written a small book about birds in northern Illinois. The younger Watson originally hoped to follow his father’s passion and become an ornithologist. “My greatest ambition had been to find out why birds migrate,” he once said. “It would have been a lost career. They still don’t know.”

At 12, the brainy boy who read the World Almanac for pleasure appeared on the popular radio show “Quiz Kids.” As is often the case for the gifted, his teen years were trying. “I never even tried to be an adolescent,” Watson said. “I never went to teenage parties. I didn’t fit in. I didn’t want to fit in. I basically passed from being a child to an adult.”

He was admitted to the University of Chicago at 15, under a program designed to give bright youngsters a head start in life. It was there he learned the Socratic method of inquiry by oral combat that would underlie both his remarkable achievements and the harsh judgments that would precipitate his fall from grace.

Reading Erwin Schrodinger’s book, “What Is Life?” in his sophomore year set the aspiring ornithologist on a new course. Schrodinger suggested that a substance he called an “aperiodic crystal,” which might be a molecule, was the substance that passed on hereditary information. Watson was inspired by the idea that if such a molecule existed, he might be able to find it.

“Goodbye bird migration,” he said, “and on to the gene.”

Coincidentally, Oswald Avery had only the year before shown that a relatively simple compound — deoxyribonucleic acid, DNA — must play a role in transferring genetic information. He injected DNA from one type of bacterium into another, then watched as the two became the same.

Most scientists didn’t believe the results. DNA, which is coiled up in every cell in the body, was nothing special, just sugars, phosphates and bases. They couldn’t believe this simple compound could be responsible for the myriad characteristics that make up an animal, much less a human being.

Watson, meanwhile, had graduated and moved on to Indiana University, where he joined a cluster of scientists known as the “phage group,” whose research with viruses infecting bacteria helped launch the field of molecular biology. He often said he came “along at the right time” to solve the DNA problem, but there was more to it. “The major credit I think Jim and I deserve is for selecting the right problem and sticking to it,” Crick said many years later. “It’s true that by blundering about we stumbled on gold, but the fact remains that we were looking for gold.”

The search began inauspiciously enough, when Watson arrived at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University in late 1951, supposedly to study proteins. Crick was 12 years older, working on his PhD. When they met, the two found an instant camaraderie. “I’m sure Francis and I talked about guessing the structure of DNA within the first half-hour of our meeting,” Watson recalled.

Their working method was mostly just conversation, but conversation conducted at a breakneck pace, and at high volume. So high, they were exiled to an office in a shabby shack called the Hut, where their debates would not disturb others.

In January 1953, the brilliant American chemist Linus Pauling stole a march on them when he announced he had the answer: DNA was a triple helix, with the bases sticking out, like charms on a bracelet.

Watson and Crick were devastated, until they realized Pauling’s scheme would not work. After seeing an X-ray image of DNA taken by crystallographer Rosalind Franklin, they built a 6-foot-tall metal model of a double helix, shaped like a spiral staircase, with the rungs made of the bases adenine and thymine, guanine and cytosine. When they finished, it was immediately apparent how DNA copies itself, by unzipping down the middle, allowing each chain to find a new partner. In Watson’s words, the final product was “too pretty” not to be true.

American biology professor James Dewey Watson from Cambridge, Nobel laureate in medicine in 1962, explains the possibilities of future cancer treatments at a Nobel Laureate Meeting in Lindau on July 4, 1967. Watson had received the Nobel Prize together with the two British scientists Crick and Wilkins for their research on the molecular structure of nucleic acids (DNA).

(Gerhard Rauchwetter / picture alliance via Getty Images)

It was true, and in 1962, Watson, Crick and another researcher, Maurice Wilkins, were awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Franklin, whose expert X-ray images solidified Watson’s conviction that DNA was a double helix, had died four years earlier of ovarian cancer. Had she lived, it’s unclear what would have happened, since Nobel rules allow only three people to share a single prize.

In the coming years, Watson’s attitude toward Franklin became a matter of controversy, which he did little to soothe by his unchivalrous treatment of her in his 1968 book, “The Double Helix.” “By choice, she did not emphasize her feminine qualities,” he wrote, adding that she was secretive and quarrelsome.

To his admirers, this was just “Honest Jim,” as some referred to him, being himself, a refreshing antidote to the increasingly politically correct world of science and society. But as the years passed, more controversies erupted around his “truth-telling” — he said he would not hire an overweight person because they were not ambitious, and that exposure to the sun in equatorial regions increases sexual urges — culminating with remarks in 2007 that he could not escape. He said he was “inherently gloomy” about Africa’s prospects because policies in the West were based on assumptions that the intelligence of Black people is the same as Europeans, when “all the testing says, not really.”

He apologized “unreservedly,” but was still forced to retire as chancellor of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, the Long Island, N.Y., institution he had rescued from the brink of insolvency decades earlier. Afterward, he complained about being reduced to a “non-person,” but rekindled public outrage seven years later by insisting in a documentary that his views had not changed. This time, citing his “unsubstantiated and reckless personal opinions,” the laboratory rescinded the honorary titles it had bestowed, chancellor emeritus and honorary trustee.

Mark Mannucci, director of the documentary “American Masters: Decoding Watson,” compared him to King Lear, a man “at the height of his powers and, through his own character flaws, was brought down.” Those sympathetic to Watson said the problem was he didn’t know any of his Black colleagues. If he had, they argued, he would have immediately renounced his prejudices.

Following his DNA triumph, Watson spent two years at Caltech before joining the faculty at Harvard University. During this period, he worked to understand the role ribonucleic acid (RNA) plays in the synthesis of proteins that make bodily structures. If the double-stranded DNA contains the body’s master plan, the single-stranded RNA is the messenger, telling the cell’s protein factories how to build the three-dimensional shapes that make the whole. Watson’s 1965 textbook, “Molecular Biology of the Gene,” became a foundation stone of modern biology.

As great as was his obsession with DNA, Watson’s pursuit of, and failure to obtain, female companionship was a matter of only marginally less critical mass. At Harvard, he recruited Radcliffe coeds to work in his lab, reasoning that “if you have pretty girls in the lab, you don’t have to go out.” He started attending Radcliffe parties known as jolly-ups. “Here comes this 35-year-old and he wants to come to jolly-ups,” said a biographer, Victor McElheny. “He was constantly swinging and missing.”

His batting average improved when he met Elizabeth Vickery Lewis, a 19-year-old Radcliffe sophomore working in the Harvard lab. He married her in 1968, realizing by only days his goal of marrying before 40. On his honeymoon, he sent a postcard back to Harvard: “She’s 19; she’s beautiful; and she’s all mine.” The couple had two sons, Rufus, who developed schizophrenia in his teens, and Duncan.

The same year, Watson finished writing “The Double Helix.” When he showed it to Crick and Wilkins, both objected to the way he characterized them and persuaded Harvard not to publish it. Watson soon found another publisher.

It was certainly true his book could be unkind and gossipy, but that was why the public, which likely had trouble sorting out the details of crystallography and hydrogen bonds, loved it. “The Double Helix” became an international bestseller that remained in stock for many years. Eventually, Watson and Crick made up and by the time the Englishman died in 2004, they were again the boon pals they’d been 50 years earlier.

After their discovery of DNA’s structure, the two men took divergent paths. Crick hoped to find the biological roots of consciousness, while Watson devoted himself to discovering a cure for cancer.

After serving on a voluntary basis, Watson became director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island in 1976. It had once been a whaling village, and the humble buildings retained a rustic charm, though when Watson arrived the rustic quality was on a steep descent toward ruination. Its endowment was virtually nonexistent and money was so tight a former director mowed the lawn himself.

As skilled at raising money as he was at solving difficult scientific problems, Watson turned the institution into a major research center that helped reveal the role of genetics in cancer. By 2019, the endowment had grown to $670 million, and the research staff had tripled. From an annual budget of $1 million, it had grown to $190 million.

“You have to like people who have money,” Watson said in explanation of his success at resurrecting Cold Spring Harbor. “I really like rich people.” His growing eccentricity, which included untied shoelaces and hair that spiked out in all directions, completed the stock image of a distracted scientist. Acquaintances swore they saw him untie his shoelaces before meeting with a potential donor.

In 1988, he became the first director of the $3-billion Human Genome Project, whose goal was to identify and map every human gene. He resigned four years later, after a public falling-out with the director of the National Institutes of Health. “I completely failed the test,” he said of his experience as a bureaucrat.

Among his passions were tennis and charity work. In 2014, the year of the documentary that sealed his fate as an exile, Watson put his Nobel gold medal up for auction. He gave away virtually all the $4.1 million it fetched. The buyer, Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov, returned it a year later, saying he felt bad the scientist had to sell possessions to support worthy causes.

A complex, beguiling, maddening man who defied easy, or any, categorization, Watson followed his own star to the end of his life, insisting in 2016, when he was nearly 90, that he didn’t want to die until a cure for cancer was found. At the time, he was still playing tennis three times a week, with partners decades younger.

Besides the Nobel Prize, Watson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Eli Lilly Award in Biochemistry and the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and was made an honorary Knight of the British Empire. Among his literary works were both scientific and popular books, from “Recombinant DNA” to “Genes, Girls, and Gamow,” a typically cheeky book recounting his twin obsessions, scientific glory and the opposite sex.

Johnson is a former Times staff writer.

Science

Nearly 40% of California produce contains PFAS pesticides, report finds

A new report shows that nearly 40% of conventionally grown fruits and vegetables tested by California regulators have residues of “forever” or PFAS chemicals, a family of compounds that can be lasting and harmful.

The Environmental Working Group, an advocacy group based in Washington, D.C., reviewed California’s own test data and found PFAS pesticide residues on peaches, grapes and strawberries, and about three dozen other types of fruits and vegetables.

The chemicals have have increasingly been used in agricultural chemicals in recent years.

“Here’s the thing: This is an emerging threat,” said Nathan Donley, environmental health science director for the Center for Biological Diversity, who was not involved in the report. “PFAS pesticides went from being the exception to now they’re the rule.”

More than 90% of nectarine, peach and plum samples tested contained the PFAS fungicide fludioxonil. The fungicide is sprayed on the fruits after harvest to prevent mold. More than 80% of the cherries, strawberries and grapes sampled carried PFAS residue.

The group relied on data collected in 2023 by California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation, a branch of CalEPA.

There are thousands of PFAS chemicals used in consumer products, electronics, pharmaceuticals and pesticides. They are prized by product manufacturers for their strength, persistence and water resistance. However, many are considered highly toxic, even at very low levels. They’ve been linked to immune suppression, cancer and reproductive and developmental health disruptions and toxicity. They’ve also been linked to ecosystem damage, harming aquatic animals and wildlife.

The vast majority of PFAS chemicals have not been tested for human health effects.

“At a time when most industries are transitioning away from PFAS chemicals, the pesticide industry is actually doubling down on them,” said Donley, who has published papers on the issue. “I think that the persistence of these chemicals is certainly playing a role” in why industries find them desirable, he said.

“But then again, you get a whole heck of a lot more collateral damage when you have a pesticide that sticks around as long as DDT does,” he said.

Regulators say that not all PFAS chemicals are the same. While some can persist for thousands of years, others break down much more quickly. They also say the ones used in approved pesticides are vetted for human health impacts, as well as ecosystem impacts — such as how they could affect pollinators, aquatic organisms and other wildlife. There are also strict usage requirements that limit the amount of chemicals applied to food, they say.

“Before any pesticide can be sold or used in California, DPR (Department of Pesticide Regulation) conducts a thorough scientific review. This includes evaluating both the active ingredients and full product formulations to understand how long the chemicals remain in the environment and how they break down, which is a key concern for PFAS compounds,” said Amy MacPherson, a spokeswoman for the pesticide agency.

In addition, she said, while the report looks at “detections” of PFAS chemicals, her agency “looks at how those detections compare to federal tolerance levels.”

She said this is important because “detection alone … does not necessarily mean there’s a health risk. Tolerance levels consider lifelong, daily exposure that pose a reasonable certainty of no harm, inclusive of chronic risk.”

Varun Subramaniam, a co-author of the report and a health data specialist with the Environmental Working Group, said he focused on California for two reasons: California’s pesticide department is one of the few, if not only, state agencies to do this kind of testing; and the state is one of the nation’s largest producers of fruits and vegetables.

“Things that are grown in California tend to spread across the country,” said Subramaniam, who is working on a national report documenting the use of these pesticides. “We thought California was a good starting point.”

Roughly 70 PFAS pesticides are registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accounting for about 14% of all active pesticide ingredients. California has registered 53 PFAS pesticides.

According to the report, about 2.5 million pounds of PFAS pesticides are applied annually on California cropland.

Both Subramaniam and Donley said states such as Maine, Rhode Island, Minnesota and North Carolina are “way ahead” of California in considering the harm these chemicals pose to people and ecosystems, and are trying to ban them.

“These chemicals are really top of mind in the East Coast, especially in New England states where … this story has been going on for decades,” he said.

Subramaniam said people should wash their produce before eating, and opt for organic fruits and vegetables when they can — organic farmers cannot use these chemicals on their produce.

Science

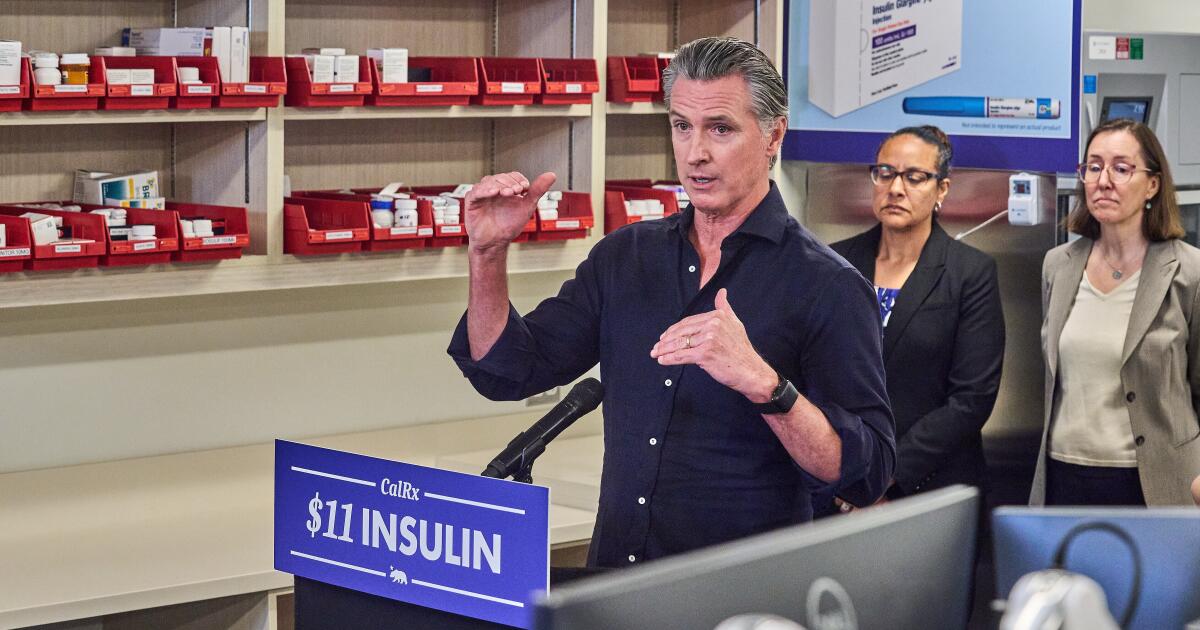

Newsom’s fight with Trump and RFK Jr. on public health

SACRAMENTO — California Gov. Gavin Newsom has positioned himself as a national public health leader by staking out science-backed policies in contrast with the Trump administration.

After Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Susan Monarez for refusing what her lawyers called “the dangerous politicization of science,” Newsom hired her to help modernize California’s public health system. He also gave a job to Debra Houry, the agency’s former chief science and medical officer, who had resigned in protest hours after Monarez’s firing.

Newsom also teamed up with fellow Democratic governors Tina Kotek of Oregon, Bob Ferguson of Washington and Josh Green of Hawaii to form the West Coast Health Alliance, a regional public health agency, whose guidance the governors said would “uphold scientific integrity in public health as Trump destroys” the CDC’s credibility. Newsom argued establishing the independent alliance was vital as Kennedy leads the Trump administration’s rollback of national vaccine recommendations.

More recently, California became the first state to join a global outbreak response network coordinated by the World Health Organization, followed by Illinois and New York. Colorado and Wisconsin signaled they plan to join. They did so after President Trump officially withdrew the United States from the agency on the grounds that it had “strayed from its core mission and has acted contrary to the U.S. interests in protecting the U.S. public on multiple occasions.” Newsom said joining the WHO-led consortium would enable California to respond faster to communicable disease outbreaks and other public health threats.

Although other Democratic governors and public health leaders have openly criticized the federal government, few have been as outspoken as Newsom, who is considering a run for president in 2028 and is in his second and final term as governor. Members of the scientific community have praised his effort to build a public health bulwark against the Trump administration’s slashing of funding and scaling back of vaccine recommendations.

What Newsom is doing “is a great idea,” said Paul Offit, an outspoken critic of Kennedy and a vaccine expert who formerly served on the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee but was removed under Trump in 2025.

“Public health has been turned on its head,” Offit said. “We have an anti-vaccine activist and science denialist as the head of U.S. Health and Human Services. It’s dangerous.”

The White House did not respond to questions about Newsom’s stance and Health and Human Services declined requests to interview Kennedy. Instead, federal health officials criticized Democrats broadly, arguing that blue states are participating in fraud and mismanagement of federal funds in public health programs.

Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard said the administration is going after “Democrat-run states that pushed unscientific lockdowns, toddler mask mandates, and draconian vaccine passports during the COVID era.” She said those moves have “completely eroded the American people’s trust in public health agencies.”

Public health guided by science

Since Trump returned to office, Newsom has criticized the president and his administration for engineering policies that he sees as an affront to public health and safety, labeling federal leaders as “extremists” trying to “weaponize the CDC and spread misinformation.” He has excoriated federal officials for erroneously linking vaccines to autism, warning that the administration is endangering the lives of infants and young children in scaling back childhood vaccine recommendations. And he argued that the White House is unleashing “chaos” on America’s public health system in backing out of the WHO.

The governor declined an interview request, but Newsom spokesperson Marissa Saldivar said it’s a priority of the governor “to protect public health and provide communities with guidance rooted in science and evidence, not politics and conspiracies.”

The Trump administration’s moves have triggered financial uncertainty that local officials said has reduced morale within public health departments and left states unprepared for disease outbreaks and prevention efforts. The White House last year proposed cutting Health and Human Services spending by $33 billion, including $3.6 billion from the CDC. Congress largely rejected those cuts last month, although funding for programs focusing on social drivers of health, such as access to food, housing and education, were axed.

The Trump administration announced that it would claw back more than $600 million in public health funds from California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota, arguing that the Democratic-led states were funding “woke” initiatives that didn’t reflect White House priorities. Within days, the states sued and a judge temporarily blocked the cut.

“They keep suddenly canceling grants and then it gets overturned in court,” said Kat DeBurgh, executive director of the Health Officers Assn. of California. “A lot of the damage is already done because counties already stopped doing the work.”

Federal funding has accounted for more than half of state and local health department budgets nationwide, with money going toward fighting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, preventing chronic diseases, and boosting public health preparedness and communicable disease response, according to a 2025 analysis by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Federal funds account for $2.4 billion of California’s $5.3-billion public health budget, making it difficult for Newsom and state lawmakers to backfill potential cuts. That money helps fund state operations and is vital for local health departments.

Funding cuts hurt all

Los Angeles County public health director Barbara Ferrer said if the federal government is allowed to cut that $600 million, the county of nearly 10 million residents would lose an estimated $84 million over the next two years, in addition to other grants for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Ferrer said the county depends on nearly $1 billion in federal funding annually to track and prevent communicable diseases and combat chronic health conditions, including diabetes and high blood pressure. Already, the county has announced the closure of seven public health clinics that provided vaccinations and disease testing, largely because of funding losses tied to federal grant cuts.

“It’s an ill-informed strategy,” Ferrer said. “Public health doesn’t care whether your political affiliation is Republican or Democrat. It doesn’t care about your immigration status or sexual orientation. Public health has to be available for everyone.”

A single case of measles requires public health workers to track down 200 potential contacts, Ferrer said.

The U.S. eliminated measles in 2000 but is close to losing that status as a result of vaccine skepticism and misinformation spread by vaccine critics. The U.S. had 2,281 confirmed cases last year, the most since 1991, with 93% in people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown. This year, the highly contagious disease has been reported at schools, airports and Disneyland.

Public health officials hope the West Coast Health Alliance can help counteract Trump by building trust through evidence-based public health guidance.

“What we’re seeing from the federal government is partisan politics at its worst and retaliation for policy differences, and it puts at extraordinary risk the health and well-being of the American people,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., a coalition of public health professionals.

Robust vaccine schedule

Erica Pan, California’s top public health officer and director of the state Department of Public Health, said the West Coast Health Alliance is defending science by recommending a more robust vaccine schedule than the federal government. California is part of a coalition suing the Trump administration over its decision to rescind recommendations for seven childhood vaccines, including for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, influenza and COVID-19.

Pan expressed deep concern about the state of public health, particularly the uptick in measles. “We’re sliding backwards,” Pan said of immunizations.

Sarah Kemble, Hawaii’s state epidemiologist, said Hawaii joined the alliance after hearing from pro-vaccine residents who wanted assurance that they would have access to vaccines.

“We were getting a lot of questions and anxiety from people who did understand science-based recommendations but were wondering, ‘Am I still going to be able to go get my shot?’” Kemble said.

Other states led mostly by Democrats have also formed alliances, with Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and several other East Coast states banding together to create the Northeast Public Health Collaborative.

Hilliard, of Health and Human Services, said that even as Democratic governors establish vaccine advisory coalitions, the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices “remains the scientific body guiding immunization recommendations in this country, and HHS will ensure policy is based on rigorous evidence and gold standard science, not the failed politics of the pandemic.”

Influencing red states

Newsom, for his part, has approved a recurring annual infusion of nearly $300 million to support the state Department of Public Health, as well as the 61 local public health agencies across California, and last year signed a bill authorizing the state to issue its own immunization guidance. It requires health insurers in California to provide patient coverage for vaccinations the state recommends even if the federal government doesn’t.

Jeffrey Singer, a doctor and senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, said decentralization can be beneficial. That’s because local media campaigns that reflect different political ideologies and community priorities may have a better chance of influencing the public.

A KFF analysis found some red states are joining blue states in decoupling their vaccine recommendations from the federal government’s. Singer said some doctors in his home state of Arizona are looking to more liberal California for vaccine recommendations.

“Science is never settled, and there are a lot of areas of this country where there are differences of opinion,” Singer said. “This can help us challenge our assumptions and learn.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.

Science

How Rising Home Insurance Costs Are Linked to Credit Scores

Two friends bought nearly identical homes last year, in the same northern Minnesota neighborhood, for the same price.

But Tara Novak pays more than twice as much for home insurance as Petra Rodriguez. The only difference? Ms. Novak has a lower credit score.

Across the country, people with weaker credit histories are paying far more for home insurance than owners with spotless records.

Where the home insurance rate gap between “fair” and “excellent” credit is higher

Home insurance premiums have risen rapidly in recent years, fueled by climate change, building costs and inflation. The price shock has rippled into the real estate market, dragging down home prices in areas vulnerable to disasters and leading insurers to abandon homeowners in risky places.

But these dynamics obscure another problem: The home insurance market has cleaved in two along a boundary defined more by a customer’s personal history than by the risk of a disaster hitting their home.

Americans with weaker credit histories, usually from missed payments or high amounts of debt, now pay significantly more for insurance, regardless of where they live, two new studies have found. While those with poor credit histories often can’t purchase homes at all, people with “fair” scores, which range from around 580 to 669, are paying twice as much in some places as people with “excellent” scores of about 800 or higher. And the gap is growing.

Insurers use a metric based on credit history known as an insurance score to set rates, and the figure tracks closely with a customer’s credit score.

The penalty for having a “fair” credit history versus an “excellent” one

States with the biggest pricing gaps

That can mean owners of identical homes, like Ms. Novak and Ms. Rodriguez, pay wildly different rates to insure them. For most people, it’s now just as expensive to have a credit score of “fair” as it is to live in an area likely to experience a disaster like a hurricane or wildfire. About 29 percent of consumers have credit scores that are categorized as “fair” or “poor.”

“There’s so many reasons people have bad credit,” Ms. Novak said. “It’s not like I’ve ever not paid a bill on time. I’m a stickler on my bills, I’m a stickler on my rent, never been late. This is not fair.”

“The choice to use credit scores in pricing means that those lower-credit home owners in risky areas are effectively subsidizing more affluent high-credit homeowners who also live in risky areas,” said Nick Graetz, assistant professor of sociology at the University for Minnesota, who wrote one of the recent papers. “So in a lot of ways, you can keep your insurance price down if you’re high income, high credit — even if you live on the coast of Florida.”

A handful of states have banned insurers from using credit data because of concerns about fairness and the potential for discrimination against low-income people and people of color, but the majority allow it.

For those with both weaker credit and high disaster risk, the combination can set them up for a downward spiral: disasters tend to be followed by decreases in credit scores as people use credit cards and bank loans to recover. That can lead to higher insurance rates, pushing monthly housing costs further out of reach.

“When a disaster hits, there’s a loss of income that occurs, and then that can impact someone’s credit score because they can’t pay their debt, they can’t pay their rent, they can’t pay their mortgage,” said Lance Triggs, executive vice president at Operation HOPE, a financial literacy nonprofit. “And now they’re faced with higher insurance premiums post-disaster.”

A working paper released today by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that homeowners with the lowest credit scores paid, on average, $550 more in 2024 for home insurance than those with the highest scores.

The findings broadly track with data from Quadrant Information Services analyzed by The New York Times, which found that, on average, lower credit scores meant higher premiums across every state that allowed the practice. Dr. Graetz used the same data set for his research, which he did in collaboration with the Consumer Federation of America and the Climate and Community Institute.

When a windstorm last year hit the home of Audrey Thayer, a city council member in Bemidji, Minn., it ripped the siding off her house and stripped shingles from her roof.

Ms. Thayer’s insurance did not cover all the damage. As she fought her insurer for more money, she opened new credit cards and bank loans to repair her home. Her credit score dropped as she tried to find a new insurance plan.

Ms. Thayer, a member of the White Earth Nation, said she was not aware that her credit score could affect her home insurance rates, even though she teaches about credit ratings at a nearby tribal college. “Most of the folks here do not have good credit,” said Ms. Thayer, whose community is one of the poorest in the state. “I did not know what a credit score was until I was 35 or so.”

In Texas, the advocacy group Texas Appleseed found that some insurers charge people with poor credit up to 12 times as much as people with excellent credit for certain policies, said Ann Baddour, the director of the nonprofit’s Fair Financial Services Project.

Higher costs have serious implications for low-income homeowners who live in the path of hurricanes, said Nadia Erosa, the operations manager at Come Dream Come Build, a nonprofit community housing development organization. After the Brownsville, Texas, region saw intense flooding last spring, some residents turned to companies offering high-interest loans to fund repairs, she said, raising the risk of the disaster-credit spiral.

“Delinquencies are going up because people cannot afford their payment,” she said.

The price of risk

Before they can get a mortgage, homebuyers are usually required by lenders to purchase home insurance.

“Households with insurance have fewer financial burdens, fewer unmet needs, they recover faster, they’re more likely to rebuild,” said Carolyn Kousky, an economist and founder of Insurance for Good, a nonprofit that focuses on finding new approaches to risk management. “Yet the people who need insurance the most are the least able to afford it.”

Insurance companies consider a variety of factors when setting the premium for a property. They might examine the age of the roof, or the area’s vulnerability to hurricanes or wildfires. They factor in how much it would cost to rebuild the house if it were damaged.

Insurers have argued that credit history is also worth considering because people with low scores tend to file more claims than those with excellent scores, an assertion that is backed up by the working paper published in the National Bureau of Economic Research today. This likely happens because people with weaker credit histories tend to have less income, and when their home is damaged, they file insurance claims for smaller fixes that a wealthier homeowner might pay for out of pocket.

Paul Tetrault, senior director at the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, a trade organization, said credit scores are a valid way to price premiums.

But others argue that using credit information to price insurance doesn’t make sense.

Because a homeowner pays for insurance upfront, “it’s not like you’re really extending a loan to the customer where you would be worried about the risk of repayment,” Ms. Kousky said. She points out that insurance companies can opt not to renew a homeowner’s policy if they believe it is too risky — a tactic they have been using with increasing frequency.

The NBER analysis found that homeowners who want to pay less for insurance should pay off debt to raise their credit score rather than replace roofs and make other improvements to avoid damage when disaster strikes.

Others believe that even if credit scores are accurate predictors of future claims, they shouldn’t be used to set premiums because that can perpetuate or worsen disparities. For example, people in their mid-20s who are Black, low-income, or grow up in impoverished regions have significantly lower credit scores than their peers, a July working paper from Opportunity Insights, a not-for-profit organization at Harvard University, found.

“When the government and the financial system mandate that we buy a product, there’s a special obligation to make sure the pricing is fair,” said Doug Heller, director of insurance at the Consumer Federation. “To me that is an absolutely solid reason, just like we don’t allow pricing based on race or income or ethnicity or religion.”

A natural experiment

A handful of states, including California and Massachusetts, have banned or limited the use of credit scores in setting home insurance premiums, despite opposition from the insurance industry.

In Nevada, where a temporary pandemic-related rule prevented insurers from using credit history to increase premiums for existing customers from 2020 to 2024, companies refunded approximately $27 million to nearly 200,000 policyholders, said Drew Pearson, a spokesman for the Nevada Division of Insurance.

Perhaps the clearest example of the effects of these bans comes from Washington State, which banned the use of credit information in setting home insurance premiums starting in June 2021. The rule immediately faced legal challenges, and was in effect for just a few months until it was overturned in court.

But the episode allowed researchers to evaluate the effect of credit factors on insurance premiums. When the rule took effect, people with the lowest credit scores saw a decrease in premiums of about $175 annually while those with the highest scores saw an increase of about $100, the NBER analysis found.

“We could see the dynamics of insurance pricing for the same households over time,” said Benjamin Keys, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, who co-authored the paper.

What homeowners paid before and after a ban on credit-based pricing in Washington State

Values compared with premiums paid by homeowners with “medium” credit scores (717 to 756)

In Minnesota, where Tara Novak, Petra Rodriguez and Audrey Thayer live, a state task force looked at ways to lower insurance costs for residents. It recently considered a ban or limit on the use of credit scores to set rates, but did not move forward with a recommendation.

Ms. Rodriguez said she doesn’t think it’s fair that her friend Ms. Novak should have to pay so much more for insurance to live in an identical house.

A credit score doesn’t capture anything about a person’s habits, or what they’re like as a tenant, or even years of on-time rent payments, she said. “It’s not who you are,” she said.

Methodology

Home insurance policy rates were supplied by Quadrant Information Services, an insurance data solutions company. The rates shown are representative of publicly sourced filings and should not be interpreted as bindable quotes. Actual individual premiums may vary.

‘States with the biggest pricing gaps’Rates shown are based on a home insurance policy with $400,000 of dwelling coverage and a $100,000 liability limit on a new home, for a homeowner age 50 or younger. Rates are averaged for all the individual company filings represented in the sample, which add up to a majority of the market share in each state but do not cover all active insurers in the state. Rates are also averaged to the state level from zip code level data.

‘The credit penalty in each state’Each insurance company incorporates credit history information differently, often using proprietary methods, so the scores do not map directly to FICO credit scores.

‘What homeowners paid before and after a ban on credit-based pricing in Washington State’Data shown are based on observations of real home insurance policies and homeowner credit scores from ICE McDash analyzed by the researchers of Blonz, Hossain, Keys, Mulder and Weill (2026). The price comparisons across credit score tiers controlled for variance in disaster risk, insurance policy characteristics, geography, and other year to year fluctuations.

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days agoU.S. Postal Service could run out of money within a year

-

Miami, FL1 week ago

Miami, FL1 week agoCity of Miami celebrates reopening of Flagler Street as part of beautification project

-

Pennsylvania6 days ago

Pennsylvania6 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death

-

Michigan2 days ago

Michigan2 days agoOperation BBQ Relief helping with Southwest Michigan tornado recovery

-

Virginia1 week ago

Virginia1 week agoGiants will hold 2026 training camp in West Virginia