Science

How Zone Zero, designed to protect California homes from wildfire, became plagued with controversy and delays

Late last month, California fire officials made a courtesy call to Los Angeles.

The state’s proposed Zone Zero regulations that would force homeowners to create an ember-resistant zone around their houses — initially planned to take effect nearly three years ago — had caused an uproar in the region. It was time for damage control.

Officials from both Cal Fire and the state’s Board of Forestry and Fire Protection visited Brentwood, the epicenter of the outrage, and Altadena, where homeowners are trying to figure out how best to rebuild, but did little to assuage the concerns of the Zone Zero proposals’ most vocal critics.

The two groups took turns pointing out homes that seemed to support their claims. The copious, contradictory anecdotal evidence provided no consensus for a path forward. For example, in the Eaton burn area, officials showed residents a home they claimed was spared thanks to its removal of vegetation near the home, but residents noted a home across the street with plenty of plants that also survived.

It was an example of what’s become an interminable debate about what should be required of homeowners in L.A.’s fire-prone areas to limit the destruction of future conflagrations.

Initial attempts by the board to create Zone Zero regulations, as required by a 2020 law, quietly fizzled out after fire officials and experts struggled to agree on how to navigate a lack of authoritative evidence for what strategies actually help protect a home — and what was reasonable to ask of residents.

The Jan. 1, 2023, deadline to create the regulations came and went with little fanfare. A month after the January fires, however, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order resurrecting the efforts and ordering the board to finish the regulations by the end of the year. As the board attempted to restart and speed-run the previous efforts through a series of public meetings, many Californians grew alarmed. They felt the draft Zone Zero requirements — which would be the strictest statewide defensible space rules on the books — were a step too far.

“The science tells us it doesn’t make sense, but they’re ignoring it because they have to come up with something,” said Thelma Waxman, president of the Brentwood Homeowners Assn.,who is working to certify neighborhoods in her area as fire safe. “If I’m going to go to my members and say, ‘OK, you need to spend $5,000 doing one thing to protect your home,’ it’s not going to be to remove hydrated vegetation.”

Instead, she wishes the state would focus on home-hardening, which has much more compelling research to support its effectiveness.

Tony Andersen, the board’s executive officer, stressed that his team wants to keep requirements evidence-based and reasonable for homeowners. “We’re listening; we’re learning,” he said.

Zone Zero is one of the many fire safety regulations tied to the fire hazard severity maps created by Cal Fire, which, while imperfect, attempt to identify the areas in California likely to see intense wildfire.

Since 2008, all new homes in California in areas that those maps determined have very high fire hazard are required to have multi-paned or fire-resistant windows that are less likely to shatter in extreme heat, mesh coverings on all vents so flying embers can’t sneak inside and ignition-resistant roofing and siding.

The state’s defensible space regulations break down the areas surrounding a home into multiple zones. Zone Two is within 100 feet of the home; in that space, homeowners must remove dead vegetation, keep grass under 4 inches and ensure that there is at least 10 feet between trees. Zone One is within 30 feet of a structure; here, residents cannot store firewood. Zone Zero, within 5 feet, is supposed to be “ember-resistant” — essentially meaning that there cannot be anything that might ignite should embers land within it.

The problem is, it’s unclear how to best create an “ember-resistant” zone. For starters, there’s just not a lot of scientific evidence demonstrating which techniques effectively limit ignitions. That’s especially true for the most controversial Zone Zero proposal: removing healthy plants.

“We have very few publications looking at home losses and vegetation patterns in Zone Zero,” said Max Moritz, a wildfire-dynamics researcher with UC Santa Barbara and the UC Cooperative Extension program.

Further complicating the problem, the board also needs to consider what is reasonable to ask of homeowners. Critics of the current proposal point out that while wooden fences and outbuildings are banned, wooden decks and doors are still fine — not because they cannot burn, but because asking residents to replace them is too big of a financial burden and they are, arguably, out of the purview of “defensible space.” And while many in the L.A. area argue they should be allowed to keep plants if they’re well-watered, the board cannot single-handedly dictate water usage for ornamental vegetation across the state.

To deal with the head-spinning complexity, the state started with a small working group in 2021 that included Cal Fire staff, local fire departments and scientists. The working group slowly grew to include more local leaders and came close to finalizing the rules with the board as it neared the Legislature’s Jan. 1, 2023, deadline. But as the parties got stuck on the final details, the deadline came and went. Zone Zero slowly fell off the meeting schedules and agendas and for two years, essentially nothing was done.

Then, L.A. burned.

In February 2025, Newsom signed an executive order pushing the board to finish the regulations by Dec. 31. As the board began hosting public hearings on the regulations, shock and frustration had set in among Californians.

To add insult to injury, Newsom’s executive order also pushed Cal Fire to release new hazard maps that the Legislature had also mandated. When the agency did that in the spring, many Californians were distraught to learn that the maps added over 300,000 acres — mostly in developed areas — into the classifications where Zone Zero will apply.

At a (now somewhat infamous) Zone Zero meeting at the Pasadena Convention Center in September — the only one to take place in Southern California — public comments stretched on for over five hours. They included several speakers more accustomed to receiving public comments than making them: The mayor of Agoura Hills, representatives for L.A. City Council members and the chair of L.A.’s Community Forest Advisory Committee.

Alongside marathon public meetings, the board received more than 4,000 letters on the regulations.

In a September report to L.A.’s City Council, the Los Angeles Fire Department and the city’s forestry committee chastised the board for failing to consult the city during the process and only holding its Pasadena meeting “after persistent pressure from local advocates … six months into the rulemaking process.” It also pointed to a 2025 study that found many home-hardening techniques play a much more significant role in protecting homes than defensible space.

Most of the Zone Zero proposals have generally received agreement or at least acceptance among the public: No wooden mulch, no wooden fence that attaches to the house, no dead vegetation and only outbuildings made of noncombustible materials. But two issues quickly took center stage in the discourse: trees and plants.

Residents have become increasingly concerned with the prospect of cutting down their trees after the working group began discussing how to handle them. However, the current proposals would not require residents to remove trees.

“It’s pretty much settled,” Andersen said. Well-maintained trees will be allowed in Zone Zero; however, what a well-maintained tree looks like “still needs to be discussed.”

What to do about vegetation like shrubs, plants and grasses within the first 5 feet of homes has proved more vexing.

Some fire officials and experts argue residents should remove all vegetation in the zone, citing examples of homes burning after plants ignited. Others say the board should continue to allow well-watered vegetation in Zone Zero, pointing to counterexamples where plants seemed to block embers from reaching a home or the water stored within them seemed to reduce the intensity of a burn.

“A hydrated plant is absorbing radiant heat up until the point of ignition, and then it’s part of the progression of the fire,” said Moritz. The question is, throughout a wildly complex range of fire scenarios, when exactly is that point reached?

In October, the advisory committee crafting the regulations took a step back from its proposal to require the removal of all living vegetation in Zone Zero and signaled it would consider allowing well-maintained plants.

As the committee remains stuck in the weeds, it’s looking more and more likely that the board will miss its deadline (for the second time).

“It’s more important that we get this right rather than have a hard timeline,” Andersen said.

Science

Trump administration declares ‘war on sugar’ in overhaul of food guidelines

The Trump administration announced a major overhaul of American nutrition guidelines Wednesday, replacing the old, carbohydrate-heavy food pyramid with one that prioritizes protein, healthy fats and whole grains.

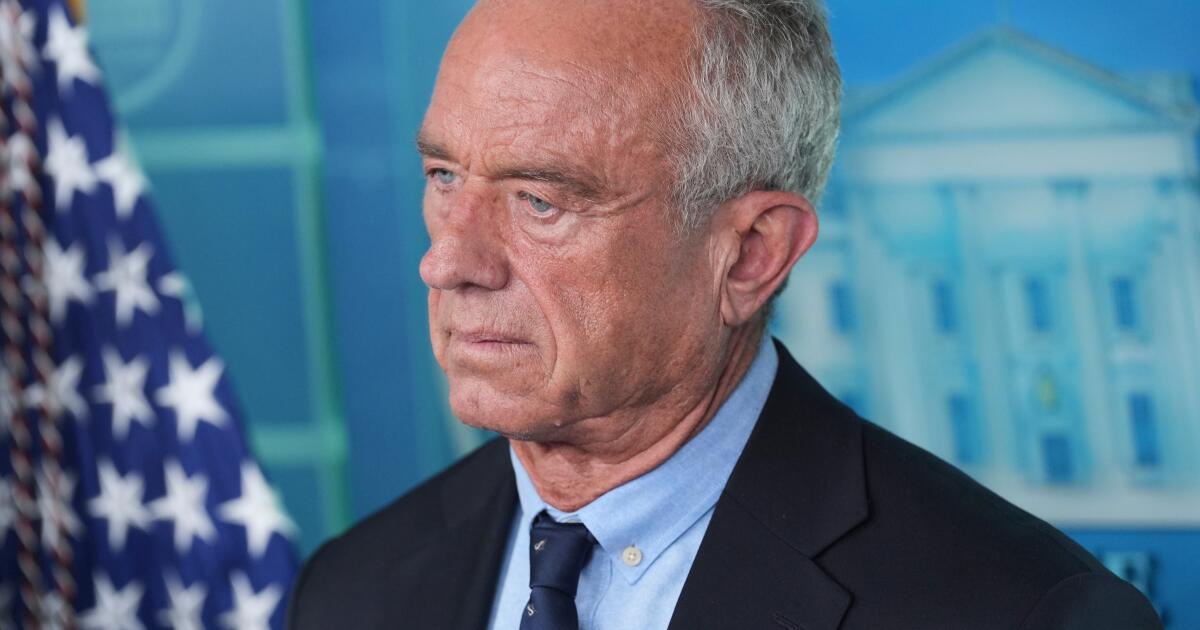

“Our government declares war on added sugar,” Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said in a White House press conference announcing the changes. “We are ending the war on saturated fats.”

“If a foreign adversary sought to destroy the health of our children, to cripple our economy, to weaken our national security, there would be no better strategy than to addict us to ultra-processed foods,” Kennedy said.

Improving U.S. eating habits and the availability of nutritious foods is an issue with broad bipartisan support, and has been a long-standing goal of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again movement.

During the press conference, he acknowledged both the American Medical Association and the American Assn. of Pediatrics for partnering on the new guidelines — two organizations that earlier this week condemned the administration’s decision to slash the number of diseases that U.S. children are vaccinated against.

“The American Medical Association applauds the administration’s new Dietary Guidelines for spotlighting the highly processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and excess sodium that fuel heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic illnesses,” AMA president Bobby Mukkamala said in a statement.

Science

Contributor: With high deductibles, even the insured are functionally uninsured

I recently saw a patient complaining of shortness of breath and a persistent cough. Worried he was developing pneumonia, I ordered a chest X-ray — a standard diagnostic tool. He refused. He hadn’t met his $3,000 deductible yet, and so his insurance would have required him to pay much or all of the cost for that scan. He assured me he would call if he got worse.

For him, the X-ray wasn’t a medical necessity, but it would have been a financial shock he couldn’t absorb. He chose to gamble on a cough, and five days later, he lost — ending up in the ICU with bilateral pneumonia. He survived, but the cost of his “savings” was a nearly fatal hospital stay and a bill that will quite likely bankrupt him. He is lucky he won’t be one of the 55,000 Americans to die from pneumonia each year.

As a physician associate in primary care, I serve as a frontline witness to this failure of the American approach to insurance. Medical professionals are taught that the barrier to health is biology: bacteria, viruses, genetics. But increasingly, the barrier is a policy framework that pressures insured Americans to gamble with their lives. High-deductible health plans seem affordable because their monthly premiums are lower than other plans’, but they create perverse incentives by discouraging patients from seeking and accepting diagnostics and treatments — sometimes turning minor, treatable issues into expensive, life-threatening emergencies. My patient’s gamble with his lungs is a microcosm of the much larger gamble we are taking with the American public.

The economic theory underpinning these high deductibles is known as “skin in the game.” The idea is that if patients are responsible for the first few thousand dollars of their care, they will become savvy consumers, shopping around for the best value and driving down healthcare costs.

But this logic collapses in the exam room. Healthcare is not a consumer good like a television or a used car. My patient was not in a position to “shop around” for a cheaper X-ray, nor was he qualified to determine if his cough was benign or deadly. The “skin in the game” theory assumes a level of medical literacy and market transparency that simply doesn’t exist in a moment of crisis. You can compare the specs of two SUVs; you cannot “shop around” for a life-saving diagnostic while gasping for air.

A 2025 poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation points to this reality, finding that up to 38% of insured American adults say they skipped or postponed necessary healthcare or medications in the past 12 months because of cost. In the same poll, 42% of those who skipped care admitted their health problem worsened as a result.

This self-inflicted public health crisis is set to deteriorate further. The Congressional Budget Office estimates roughly 15 million people will lose health coverage and become uninsured by 2034 because of Medicaid and Affordable Care Act marketplace cuts. That is without mentioning the millions more who will see their monthly premiums more than double if premium tax credits are allowed to expire. If that happens, not only will millions become uninsured but also millions more will downgrade to “bronze” plans with huge deductibles just to keep their premiums affordable. We are about to flood the system with “insured but functionally uninsured” patients.

I see the human cost of this “functional uninsurance” every week. These are patients who technically have coverage but are terrified to use it because their deductibles are so large they may exceed the individuals’ available cash or credit — or even their net worth. This creates a dangerous paradox: Americans are paying hundreds of dollars a month for a card in their wallet they cannot afford to use. They skip the annual physical, ignore the suspicious mole and ration their insulin — all while technically insured. By the time they arrive at my clinic, their disease has often progressed to a catastrophic event, from what could have been a cheap fix.

Federal spending on healthcare should not be considered charity; it is an investment in our collective future. We cannot expect our children to reach their full potential or our workforce to remain productive if basic healthcare needs are treated as a luxury. Inaction by Congress and the current administration to solve this crisis is legislative malpractice.

In medicine, we are trained to treat the underlying disease, not just the symptoms. The skipped visits and ignored prescriptions are merely symptoms; the disease is a policy framework that views healthcare as a commodity rather than a fundamental necessity. If we allow these cuts to proceed, we are ensuring that the American workforce becomes sicker, our hospitals more overwhelmed and our economy less resilient. We are walking willingly into a public health crisis that is entirely preventable.

Joseph Pollino is a primary care physician associate in Nevada.

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

-

High-deductible health plans create a barrier to necessary medical care, with patients avoiding diagnostics and treatments due to out-of-pocket cost concerns[1]. Research shows that 38% of insured American adults skipped or postponed necessary healthcare or medications in the past 12 months because of cost, with 42% reporting their health worsened as a result[1].

-

The economic theory of “skin in the game”—which assumes patients will shop around for better healthcare values if they have financial responsibility—fails in medical practice because patients lack the medical literacy to make informed decisions in moments of crisis and cannot realistically compare pricing for emergency or diagnostic services[1].

-

Rising deductibles are pushing enrollees toward bronze plans with deductibles averaging $7,476 in 2026, up from the average silver plan deductible of $5,304[1][4]. In California’s Covered California program, bronze plan enrollment has surged to more than one-third of new enrollees in 2026, compared to typically one in five[1].

-

Expiring federal premium tax credits will more than double out-of-pocket premiums for ACA marketplace enrollees in 2026, creating an expected 75% increase in average out-of-pocket premium payments[5]. This will force millions to either drop coverage or downgrade to bronze plans with massive deductibles, creating a population of “insured but functionally uninsured” people[1].

-

High-deductible plans pose particular dangers for patients with chronic conditions, with studies showing adults with diabetes involuntarily switched to high-deductible plans face 11% higher risk of hospitalization for heart attacks, 15% higher risk for strokes, and more than double the likelihood of blindness or end-stage kidney disease[4].

Different views on the topic

-

Expanding access to health savings accounts paired with bronze and catastrophic plans offers tax advantages that allow higher-income individuals to set aside tax-deductible contributions for qualified medical expenses, potentially offsetting higher out-of-pocket costs through strategic planning[3].

-

Employers and insurers emphasize that offering multiple plan options with varying deductibles and premiums enables employees to select plans matching their individual needs and healthcare usage patterns, allowing those who rarely use healthcare to save money through lower premiums[2]. Large employers increasingly offer three or more medical plan choices, with the expectation that employees choosing the right plan can unlock savings[2].

-

The expansion of catastrophic plans with streamlined enrollment processes and automatic display on HealthCare.gov is intended to make affordable coverage more accessible for certain income groups, particularly those above 400% of federal poverty level who lose subsidies[3].

-

Rising healthcare costs, including specialty drugs and new high-cost cell and gene therapies, are significant drivers requiring premium increases regardless of plan design[5]. Some insurers are managing affordability by discontinuing costly coverage—such as GLP-1 weight-loss medications—to reduce premium rate increases for broader plan members[5].

Science

Trump administration slashes number of diseases U.S. children will be regularly vaccinated against

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced sweeping changes to the pediatric vaccine schedule on Monday, sharply cutting the number of diseases U.S. children will be regularly immunized against.

Under the new guidelines, the U.S. still recommends that all children be vaccinated against measles, mumps, rubella, polio, pertussis, tetanus, diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), pneumococcal disease, human papillomavirus (HPV) and varicella, better known as chickenpox.

Vaccines for all other diseases will now fall into one of two categories: recommended only for specific high-risk groups, or available through “shared clinical decision-making” — the administration’s preferred term for “optional.”

These include immunizations for hepatitis A and B, rotavirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), bacterial meningitis, influenza and COVID-19. All these shots were previously recommended for all children.

Insurance companies will still be required to fully cover all childhood vaccines on the CDC schedule, including those now designated as optional, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a longtime vaccine critic, said in a statement that the new schedule “protects children, respects families, and rebuilds trust in public health.”

But pediatricians and public health officials widely condemned the shift, saying that it would lead to more uncertainty for patients and a resurgence of diseases that had been under control.

“The decision to weaken the childhood immunization schedule is misguided and dangerous,” said Dr. René Bravo, a pediatrician and president of the California Medical Assn. “Today’s decision undermines decades of evidence-based public health policy and sends a deeply confusing message to families at a time when vaccine confidence is already under strain.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics condemned the changes as “dangerous and unnecessary,” and said that it will continue to publish its own schedule of recommended immunizations. In September, California, Oregon, Washington and Hawaii announced that those four states would follow an independent immunization schedule based on recommendations from the AAP and other medical groups.

The federal changes have been anticipated since December, when President Trump signed a presidential memorandum directing the health department to update the pediatric vaccine schedule “to align with such scientific evidence and best practices from peer, developed countries.”

The new U.S. vaccination guidelines are much closer to those of Denmark, which routinely vaccinates its children against only 10 diseases.

As doctors and public health experts have pointed out, Denmark also has a robust system of government-funded universal healthcare, a smaller and more homogenous population, and a different disease burden.

“The vaccines that are recommended in any particular country reflect the diseases that are prevalent in that country,” said Dr. Kelly Gebo, dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. “Just because one country has a vaccine schedule that is perfectly reasonable for that country, it may not be at all reasonable” elsewhere.

Almost every pregnant woman in Denmark is screened for hepatitis B, for example. In the U.S., less than 85% of pregnant women are screened for the disease.

Instead, the U.S. has relied on universal vaccination to protect children whose mothers don’t receive adequate care during pregnancy. Hepatitis B has been nearly eliminated in the U.S. since the vaccine was introduced in 1991. Last month, a panel of Kennedy appointees voted to drop the CDC’s decades-old recommendation that all newborns be vaccinated against the disease at birth.

“Viruses and bacteria that were under control are being set free on our most vulnerable,” said Dr. James Alwine, a virologist and member of the nonprofit advocacy group Defend Public Health. “It may take one or two years for the tragic consequences to become clear, but this is like asking farmers in North Dakota to grow pineapples. It won’t work and can’t end well.”

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX5 days ago

Dallas, TX5 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Missouri3 days ago

Missouri3 days agoDamon Wilson II, Missouri DE in legal dispute with Georgia, to re-enter transfer portal: Source