Science

Hours on hold, limited appointments: Why California babies aren’t going to the doctor

Maria Mercado’s 5- and 7-year-old daughters haven’t been to the doctor for a check-up in two years. And it’s not for lack of trying.

Mercado, a factory worker in South Los Angeles, has called the pediatrician’s office over and over hoping to book an appointment for a well-child visit, only to be told there are no appointments available and to call back in a month. Sometimes, she waits on hold for an hour. Like more than half of children in California, Mercado’s daughters have Medi-Cal, the state’s health insurance program for low-income residents.

Her children are two years behind on their vaccinations. Mercado isn’t sure if they’re growing well, and they haven’t been screened for vision, hearing or developmental delays. Her older daughter has developed a stutter, and she worries the girl might need speech therapy.

“It is frustrating because as a mom, you want your kids to hit every milestone,” she said. “And if you see something’s going on and they’re not helping you, it’s like, what am I supposed to do at this point?”

Faye Holmes with 4-year-old sons Robbie, left, and JoJo, right, waits for a nurse to administer shots.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

California — where 97% of children have health insurance — ranks 46th out of all 50 states and the District of Columbia for providing a preventive care visit for kids 5 and under, according to a 2022 federal government survey. A recent report card from Children Now, a nonprofit advocacy group, rated California a D on children’s access to preventive care, despite the state’s A- grade for ensuring children have coverage.

The majority of California’s youngest residents — including 1.4 million children ages 5 and under — rely on Medi-Cal, an infrastructure ill-equipped to serve them. The state has been criticized in two consecutive audits in the past five years for failing to hold Medi-Cal insurance plans accountable for providing the necessary preventive care to the children they are paid to cover.

In a written response to questions from The Times, the Department of Health Care Services, the state agency in charge of the Medi-Cal program, said “improving children’s preventive care is one of DHCS’ top priorities,” and that the agency has recently addressed most of the shortcomings identified in the audits.

The department’s focus on the pandemic slowed action on the audit findings, the response said. State healthcare officials have since begun to more harshly fine plans that don’t provide adequate care and substantially boost payments to pediatricians to help increase access.

But information released publicly this month by the department suggests serious problems remain.

“In the whole scheme of the U.S. health system, I hate to say it, the youngest kids are always the ones that are overlooked,” said Dr. Alice Kuo, a pediatrician and health policy professor at UCLA.

According to state Medi-Cal data from 2021, the most recent year for which detailed data are available, and assessments from health experts, the impact is sobering:

- 60% of babies did not get their recommended well-child visits in the first 15 months of life. Access was even worse for Black babies — 75% did not receive their recommended screenings. Children who do not attend their well-child visits are more likely to go to the emergency room and be hospitalized for illnesses like asthma.

- 65% of 2-year-olds were not fully vaccinated, leaving them vulnerable to preventable diseases like measles and whooping cough.

- Half of children did not receive a lead screening by their second birthday; families may not know if their homes or other environments are unsafe, which raises the potential for irreversible damage.

- 71% of children did not receive their recommended developmental screening in their first three years. Without routine screenings, less than half of children with developmental or behavioral disorders are detected before kindergarten and miss out on early interventions.

“There’s a lot that happens in a well-child visit that keeps the child healthy in the immediate and the long term,” said Dr. Yasangi Jayasinha, a pediatrician with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. A doctor must ensure that a child is growing and developing normally, getting the proper nutrition, and help the family get plugged into other needed resources like food and housing assistance.

Anthony Serrano’s mother, Alexia Peralta, spent months in limbo trying to get her son re-enrolled in Medi-Cal.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“No state is perfect, but it is particularly concerning that California isn’t at least in the middle of the pack, given its focus on young children and the importance of early brain development,” said Elisabeth Wright Burak, who studies child health policy at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s Center for Children and Families.

A growing problem

There are myriad reasons for California’s poor rates of preventive care for children, according to health experts across the state: a shortage of pediatricians who accept Medi-Cal, especially in rural parts of the state; transportation issues for families who don’t have a car; difficulties getting time off work to take a child to a doctor’s appointment; a byzantine Medi-Cal bureaucracy that makes coverage difficult to use for patients.

In 2019, a California State Auditor report found that less than half of children with Medi-Cal received their recommended preventive care. The audit blamed low reimbursement rates to Medi-Cal physicians, as well as poor state oversight, and gave the department a list of fixes.

Three years later, the auditor released a follow-up report, saying that the department had failed to fully implement eight of the 14 recommendations, including making sure directories of available providers are accurate and requiring health plans to address barriers to care.

The 2022 report found access had grown even worse, a decline largely attributed to the pandemic. Just 42% of children in Medi-Cal received their recommended preventive care. An average of 2.9 million children were missing out on care each year.

For the youngest children the results were particularly troubling: 60% of 1-year-olds and 73% of 2-year-olds in Medi‑Cal did not receive the required number of preventive services.

Although federal law requires that families have access to primary care within 10 miles or 30 minutes of their home, the health department had issued more than 10,000 exceptions. In Monterey County, for example, a healthcare plan requires families to travel up to 58 miles to see a pediatrician.

The department has since implemented all but one of the recommendations it agreed to, and is in the process of overhauling the Medi-Cal program, the response said. This includes beginning to levy higher fines against Medi-Cal plans that do not provide recommended well-child visits, vaccinations and lead screenings to enough children.

A spokesperson for the state auditor’s office said the department has not proved that it has implemented three of the recommendations.

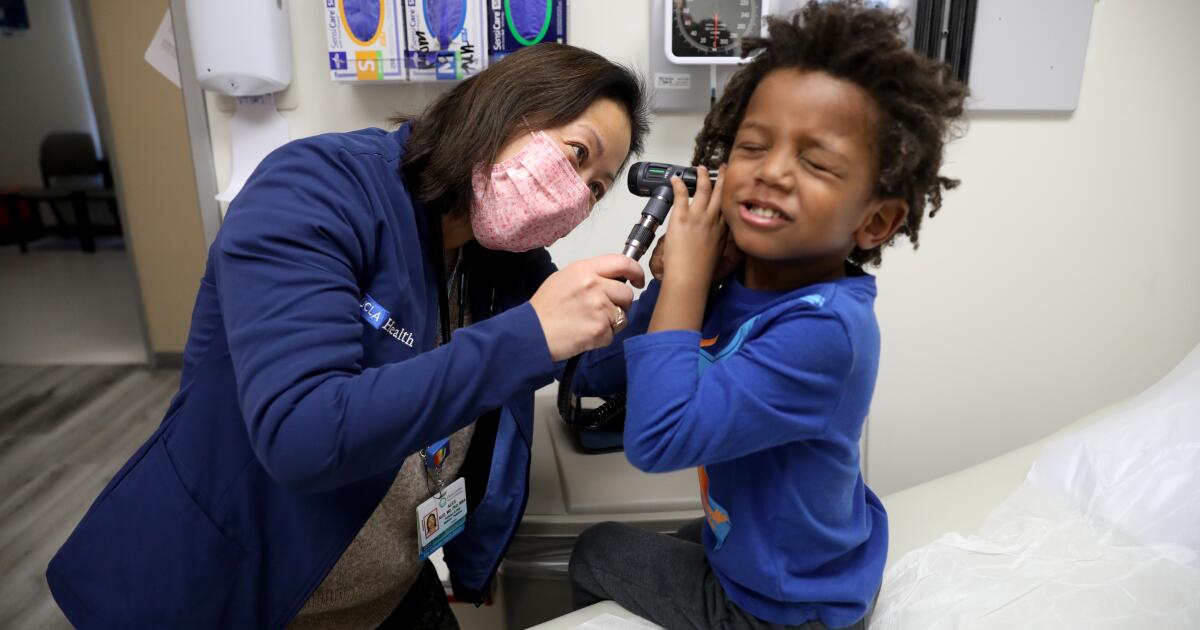

Dr. Alice Kuo performs a well-child visit with 4-year-old patients Robbie, left, and JoJo, with help from their mother, Faye Holmes.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

This month, the department announced assessments and fines for 2022. While DHCS reported some progress on access to well-child visits, the plans continued to struggle overall, and the quality of children’s healthcare lagged behind measures for other types of care, including behavioral health and chronic disease management.

Only one plan met all of the minimum standards on children’s health: Community Health Group Partnership Plan in San Diego. Eighteen out of 25 plans were fined $25,000-$890,000 for poor performance, including for children’s health.

Long waits, long drives

Parents and advocates say getting care for children remains a daily challenge. About 11 million Californians live in a primary care shortage area, where a pediatrician can be difficult to find.

“It’s most of the state, not just the Central Valley,” said Kathryn E. Phillips, an associate director at the California Health Care Foundation. California has not trained enough new doctors to meet the needs of the population, she said, and the current workforce is aging. In rural areas in particular, it can be difficult to recruit new pediatricians to join a practice.

Historically, Medi-Cal has paid doctors far less than other insurers, and the program has struggled to find enough willing to accept the rates. In 2021, for example, Medi-Cal paid $37 for a checkup with a toddler.

For the record:

2:27 p.m. Feb. 26, 2024An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the name of pediatrician Eric Ball as Eric Bell.

“Medi-Cal patients basically don’t keep the lights on. You can’t make ends meet,” said Dr. Eric Ball, a pediatrician in Orange County. About a quarter of his patients have Medi-Cal, but the practice stays afloat because of payments from privately insured patients. That may change as the state has increased the Medi-Cal rates significantly this year, up to $116 for a toddler checkup.

In Los Angeles, families often face long wait times to get an appointment with a Medi-Cal provider— 82% of children in the county did not receive a developmental screening in the first three years, 2020 state data showed.

At UCLA, Kuo said patients at her practice must book their well-child visits three to six months in advance. “We get patients coming from Palm Springs to UCLA because there’s no access.”

Are you a SoCal mom?

The L.A. Times early childhood team wants to connect with you! Find us in The Mamahood’s mom group on Facebook.

Share your perspective and ask us questions.

Many Californians — especially those with low incomes — can’t afford the costs or time to make such a long drive, especially for the multiple visits recommended each year for a baby or toddler. Medi-Cal provides a transportation benefit to members, but many families don’t know it exists or say it is difficult to arrange.

“Families are so stressed about housing. They’re stressed about the price of gas. The cost of living here is so high,” said Dr. Lisa Chamberlain, a professor of pediatrics at the Stanford School of Medicine. A doctor’s visit for a seemingly healthy child is “just not going to make it to the top of the list.”

Rosa Benito, 21, lives with her parents and five siblings in Thermal, a town in Riverside County, where the family works in agricultural fields. Getting her siblings to the doctor is a constant struggle.

“We just have my dad and his little gray car, ” she said. The family goes to a clinic in Moreno Valley, over an hour away, but it’s only open during the workday, and their farming jobs don’t offer sick time. Taking a child to the doctor means missing work, which they can’t afford.

And since her parents lack documentation to be in the country legally, they’re scared of the long travel to the clinic for fear that they’ll be pulled over by Border Patrol. “It just turns into a bigger problem. The kids would be without a guardian,” explained Benito. Unless there’s an emergency, the trip often isn’t worth it.

Luz Gallegos of TODEC, a legal center in the Inland Empire serving immigrants and farmworkers, said many families stick with traditional “remedios” for their children and only bring them to the doctor for vaccines when it’s time to enroll in kindergarten. Some have lingering fears that using their child’s Medi-Cal benefits could affect their immigration status.

“Our families don’t think about prevention. They think about surviving.”

The Medi-Cal problem

While family challenges can play a role in missed visits, the state auditor found that the blame for California’s poor performance fell largely on the Medi-Cal program.

“By failing to prioritize implementing our recommendations, DHCS has… left certain children at risk of lifelong health consequences,” the auditors wrote in their 2022 report.

Celia Valdez, director of health outreach and navigation at Maternal Child Health Access, an L.A. nonprofit that manages several social service programs, says they hear daily from families who don’t know how to navigate the Medi-Cal bureaucracy: missing insurance cards, an unexplained switch in their assigned pediatrician, coverage that is suddenly terminated. “People are lost, and by the time they get to someone who can help them, critical time has passed,” said Valdez.

Alexia Peralta kisses her son, Anthony Serrano, at their apartment in Hawthorne. A nonprofit helped her re-enroll Anthony in Medi-Cal after seven months in limbo.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

For Alexia Peralta of Hawthorne, the problems started about two months after her son was born last year, when his Medi-Cal enrollment went awry. She tried to book his 4-month well-child visit and was told he didn’t have coverage; she would have to pay $145 for the visit — an impossible sum.

She spent seven months in limbo — calling Medi-Cal repeatedly, waiting on hold for hours to speak with someone in Spanish, only to be disconnected. Several times, she thought she’d solved the problem, only to get to the pediatrician’s office and be turned away.

“I feel frustrated, mad and sad. I tried to get all these things for my child and got the run-around,” she said. He missed both his 4-month and 6-month vaccines.

Eventually, with the help of a home visitor from a Shields for Families program, a nonprofit in L.A., Peralta was able to get her son re-enrolled. At 15 months, he is still catching up on his vaccines.

Trying to fix the system

The health department said the challenges are not unique to California, and that the pandemic “resulted in large backlogs of children who needed to catch up on preventive services, a worsening crisis in the health care workforce, and limited additional capacity for pediatric services.”

In response, the department “has made historic investments and launched new initiatives” that “look to lift our youngest Californians and allow them to be healthy and to thrive.” This includes sending educational materials to families about recommended care, creating new contracts with Medi-Cal plans that more closely track children’s healthcare, and continuing to fine plans that fail to perform.

The state is also pumping money into the primary care workforce and is expanding residency and loan repayment programs. There are new Medi-Cal benefits to pay for doulas and community health workers, who can help patients navigate care, the response said.

Sayra Peralta dances with her grandson, Anthony Serrano, as her daughter, Alexia Peralta, looks on.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“The big ship is slowly turning,” said Mike Odeh, senior director of health at Children Now, who serves in an advisory group for the department. “But I want to emphasize how big the ship is and how hard it is to turn, given that we have decades of plans not providing care for kids. Changing that is going to take a lot of work.”

Former State Sen. Richard Pan, who was chair of the Health Committee before terming out in 2022, said he is not yet convinced the department’s response to the audits has been adequate. The devil is in the details, he said — are the fines against plans high enough? And how many plans will end up complying?

“Give us the proof that it’s been fixed. Show us the data. Unfortunately, I’m not in a position now to hold hearings, but I think that’s the next follow through,” he said. “The buck should always stop at the state.”

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

Science

Commentary: My toothache led to a painful discovery: The dental care system is full of cavities as you age

I had a nagging toothache recently, and it led to an even more painful revelation.

If you X-rayed the state of oral health care in the United States, particularly for people 65 and older, the picture would be full of cavities.

“It’s probably worse than you can even imagine,” said Elizabeth Mertz, a UC San Francisco professor and Healthforce Center researcher who studies barriers to dental care for seniors.

Mertz once referred to the snaggletoothed, gap-filled oral health care system — which isn’t really a system at all — as “a mess.”

But let me get back to my toothache, while I reach for some painkiller. It had been bothering me for a couple of weeks, so I went to see my dentist, hoping for the best and preparing for the worst, having had two extractions in less than two years.

Let’s make it a trifecta.

My dentist said a molar needed to be yanked because of a cellular breakdown called resorption, and a periodontist in his office recommended a bone graft and probably an implant. The whole process would take several months and cost roughly the price of a swell vacation.

I’m lucky to have a great dentist and dental coverage through my employer, but as anyone with a private plan knows, dental insurance can barely be called insurance. It’s fine for cleanings and basic preventive routines. But for more complicated and expensive procedures — which multiply as you age — you can be on the hook for half the cost, if you’re covered at all, with annual payout caps in the $1,500 range.

“The No. 1 reason for delayed dental care,” said Mertz, “is out-of-pocket costs.”

So I wondered if cost-wise, it would be better to dump my medical and dental coverage and switch to a Medicare plan that costs extra — Medicare Advantage — but includes dental care options. Almost in unison, my two dentists advised against that because Medicare supplemental plans can be so limited.

Sorting it all out can be confusing and time-consuming, and nobody warns you in advance that aging itself is a job, the benefits are lousy, and the specialty care you’ll need most — dental, vision, hearing and long-term care — are not covered in the basic package. It’s as if Medicare was designed by pranksters, and we’re paying the price now as the percentage of the 65-and-up population explodes.

So what are people supposed to do as they get older and their teeth get looser?

A retired friend told me that she and her husband don’t have dental insurance because it costs too much and covers too little, and it turns out they’re not alone. By some estimates, half of U.S. residents 65 and older have no dental insurance.

That’s actually not a bad option, said Mertz, given the cost of insurance premiums and co-pays, along with the caps. And even if you’ve got insurance, a lot of dentists don’t accept it because the reimbursements have stagnated as their costs have spiked.

But without insurance, a lot of people simply don’t go to the dentist until they have to, and that can be dangerous.

“Dental problems are very clearly associated with diabetes,” as well as heart problems and other health issues, said Paul Glassman, associate dean of the California Northstate University dentistry school.

There is one other option, and Mertz referred to it as dental tourism, saying that Mexico and Costa Rica are popular destinations for U.S. residents.

“You can get a week’s vacation and dental work and still come out ahead of what you’d be paying in the U.S.,” she said.

Tijuana dentist Dr. Oscar Ceballos told me that roughly 80% of his patients are from north of the border, and come from as far away as Florida, Wisconsin and Alaska. He has patients in their 80s and 90s who have been returning for years because in the U.S. their insurance was expensive, the coverage was limited and out-of-pocket expenses were unaffordable.

“For example, a dental implant in California is around $3,000-$5,000,” Ceballos said. At his office, depending on the specifics, the same service “is like $1,500 to $2,500.” The cost is lower because personnel, office rent and other overhead costs are cheaper than in the U.S., Ceballos said.

As we spoke by phone, Ceballos peeked into his waiting room and said three patients were from the U.S. He handed his cellphone to one of them, San Diegan John Lane, who said he’s been going south of the border for nine years.

“The primary reason is the quality of the care,” said Lane, who told me he refers to himself as 39, “with almost 40 years of additional” time on the clock.

Ceballos is “conscientious and he has facilities that are as clean and sterile and as medically up to date as anything you’d find in the U.S.,” said Lane, who had driven his wife down from San Diego for a new crown.

“The cost is 50% less than what it would be in the U.S.,” said Lane, and sometimes the savings is even greater than that.

Come this summer, Lane may be seeing even more Californians in Ceballos’ waiting room.

“Proposed funding cuts to the Medi-Cal Dental program would have devastating impacts on our state’s most vulnerable residents,” said dentist Robert Hanlon, president of the California Dental Assn.

Dental student Somkene Okwuego smiles after completing her work on patient Jimmy Stewart, 83, who receives affordable dental work at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC on the USC campus in Los Angeles on February 26, 2026.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Under Proposition 56’s tobacco tax in 2016, supplemental reimbursements to dentists have been in place, but those increases could be wiped out under a budget-cutting proposal. Only about 40% of the state’s dentists accept Medi-Cal payments as it is, and Hanlon told me a CDA survey indicates that half would stop accepting Medi-Cal patients and many others will accept fewer patients.

“It’s appalling that when the cost of providing healthcare is at an all-time high, the state is considering cutting program funding back to 1990s levels,” Hanlon said. “These cuts … will force patients to forgo or delay basic dental care, driving completely preventable emergencies into already overcrowded emergency departments.”

Somkene Okwuego, who as a child in South L.A. was occasionally a patient at USC’s Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry clinic, will graduate from the school in just a few months.

I first wrote about Okwuego three years ago, after she got an undergrad degree in gerontology, and she told me a few days ago that many of her dental patients are elderly and have Medi-Cal or no insurance at all. She has also worked at a Skid Row dental clinic, and plans after graduation to work at a clinic where dental care is free or discounted.

Okwuego said “fixing the smiles” of her patients is a privilege and boosts their self-image, which can help “when they’re trying to get jobs.” When I dropped by to see her Thursday, she was with 83-year-old patient Jimmy Stewart.

Stewart, an Army veteran, told me he had trouble getting dental care at the VA and had gone years without seeing a dentist before a friend recommended the Ostrow clinic. He said he’s had extractions and top-quality restorative care at USC, with the work covered by his Medi-Cal insurance.

I told Stewart there could be some Medi-Cal cuts in the works this summer.

“I’d be screwed,” he said.

Him and a lot of other people.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

Science

Diablo Canyon clears last California permit hurdle to keep running

Central Coast Water authorities approved waste discharge permits for Diablo Canyon nuclear plant Thursday, making it nearly certain it will remain running through 2030, and potentially through 2045.

The Pacific Gas & Electric-owned plant was originally supposed to shut down in 2025, but lawmakers extended that deadline by five years in 2022, fearing power shortages if a plant that provides about 9 percent the state’s electricity were to shut off.

In December, Diablo Canyon received a key permit from the California Coastal Commission through an agreement that involved PG&E giving up about 12,000 acres of nearby land for conservation in exchange for the loss of marine life caused by the plant’s operations.

Today’s 6-0 vote by the Central Coast Regional Water Board approved PG&E’s plans to limit discharges of pollutants into the water and continue to run its “once-through cooling system.” The cooling technology flushes ocean water through the plant to absorb heat and discharges it, killing what the Coastal Commission estimated to be two billion fish each year.

The board also granted the plant a certification under the Clean Water Act, the last state regulatory hurdle the facility needed to clear before the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is allowed to renew its permit through 2045.

The new regional water board permit made several changes since the last one was issued in 1990. One was a first-time limit on the chemical tributyltin-10, a toxic, internationally-banned compound added to paint to prevent organisms from growing on ship hulls.

Additional changes stemmed from a 2025 Supreme Court ruling that said if pollutant permits like this one impose specific water quality requirements, they must also specify how to meet them.

The plant’s biggest water quality impact is the heated water it discharges into the ocean, and that part of the permit remains unchanged. Radioactive waste from the plant is regulated not by the state but by the NRC.

California state law only allows the plant to remain open to 2030, but some lawmakers and regulators have already expressed interest in another extension given growing electricity demand and the plant’s role in providing carbon-free power to the grid.

Some board members raised concerns about granting a certification that would allow the NRC to reauthorize the plant’s permits through 2045.

“There’s every reason to think the California entities responsible for making the decision about continuing operation, namely the California [Independent System Operator] and the Energy Commission, all of them are sort of leaning toward continuing to operate this facility,” said boardmember Dominic Roques. “I’d like us to be consistent with state law at least, and imply that we are consistent with ending operation at five years.”

Other board members noted that regulators could revisit the permits in five years or sooner if state and federal laws changes, and the board ultimately approved the permit.

Science

Deadly bird flu found in California elephant seals for the first time

The H5N1 bird flu virus that devastated South American elephant seal populations has been confirmed in seals at California’s Año Nuevo State Park, researchers from UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz announced Wednesday.

The virus has ravaged wild, commercial and domestic animals across the globe and was found last week in seven weaned pups. The confirmation came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa.

“This is exceptionally rapid detection of an outbreak in free-ranging marine mammals,” said Professor Christine Johnson, director of the Institute for Pandemic Insights at UC Davis’ Weill School of Veterinary Medicine. “We have most likely identified the very first cases here because of coordinated teams that have been on high alert with active surveillance for this disease for some time.”

Since last week, when researchers began noticing neurological and respoiratory signs of the disease in some animals, 30 seals have died, said Roxanne Beltran, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. Twenty-nine were weaned pups and the other was an adult male. The team has so far confirmed the virus in only seven of the dead pups.

Infected animals often have tremors convulsions, seizures and muscle weakness, Johnson said.

Beltran said teams from UC Santa Cruz, UC Davis and California State Parks monitor the animals 260 days of the year, “including every day from December 15 to March 1” when the animals typically come ashore to breed, give birth and nurse.

The concerning behavior and deaths were first noticed Feb. 19.

“This is one of the most well-studied elephant seal colonies on the planet,” she said. “We know the seals so well that it’s very obvious to us when something is abnormal. And so my team was out that morning and we observed abnormal behaviors in seals and increased mortality that we had not seen the day before in those exact same locations. So we were very confident that we caught the beginning of this outbreak.”

In late 2022, the virus decimated southern elephant seal populations in South America and several sub-Antarctic Islands. At some colonies in Argentina, 97% of pups died, while on South Georgia Island, researchers reported a 47% decline in breeding females between 2022 and 2024. Researchers believe tens of thousands of animals died.

More than 30,000 sea lions in Peru and Chile died between 2022 and 2024. In Argentina, roughly 1,300 sea lions and fur seals perished.

At the time, researchers were not sure why northern Pacific populations were not infected, but suspected previous or milder strains of the virus conferred some immunity.

The virus is better known in the U.S. for sweeping through the nation’s dairy herds, where it infected dozens of dairy workers, millions of cows and thousands of wild, feral and domestic mammals. It’s also been found in wild birds and killed millions of commercial chickens, geese and ducks.

Two Americans have died from the virus since 2024, and 71 have been infected. The vast majority were dairy or commercial poultry workers. One death was that of a Louisiana man who had underlying conditions and was believed to have been exposed via backyard poultry or wild birds.

Scientists at UC Santa Cruz and UC Davis increased their surveillance of the elephant seals in Año Nuevo in recent years. The catastrophic effect of the disease prompted worry that it would spread to California elephant seals, said Beltran, whose lab leads UC Santa Cruz’s northern elephant seal research program at Año Nuevo.

Johnson, the UC Davis researcher, said the team has been working with stranding networks across the Pacific region for several years — sampling the tissue of birds, elephant seals and other marine mammals. They have not seen the virus in other California marine mammals. Two previous outbreaks of bird flu in U.S. marine mammals occurred in Maine in 2022 and Washington in 2023, affecting gray and harbor seals.

The virus in the animals has not yet been fully sequenced, so it’s unclear how the animals were exposed.

“We think the transmission is actually from dead and dying sea birds” living among the sea lions, Johnson said. “But we’ll certainly be investigating if there’s any mammal-to-mammal transmission.”

Genetic sequencing from southern elephant seal populations in Argentina suggested that version of the virus had acquired mutations that allowed it to pass between mammals.

The H5N1 virus was first detected in geese in China in 1996. Since then it has spread across the globe, reaching North America in 2021. The only continent where it has not been detected is Oceania.

Año Nuevo State Park, just north of Santa Cruz, is home to a colony of some 5,000 elephant seals during the winter breeding season. About 1,350 seals were on the beach when the outbreak began. Other large California colonies are located at Piedras Blancas and Point Reyes National Sea Shore. Most of those animals — roughly 900 — are weaned pups.

It’s “important to keep this in context. So far, avian influenza has affected only a small proportion of the weaned at this time, and there are still thousands of apparently healthy animals in the population,” Beltran said in a press conference.

Public access to the park has been closed and guided elephant seal tours canceled.

Health and wildlife officials urge beachgoers to keep a safe distance from wildlife and keep dogs leashed because the virus is contagious.

-

World4 days ago

World4 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Denver, CO4 days ago

Denver, CO4 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana7 days ago

Louisiana7 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT