Vermont

Vermont’s Foster Care IT System Predates the Internet — And Puts Kids at Risk

Support The 74’s year-end campaign. Make a tax-exempt donation now.

Erinn Rolland-Forkey has been a foster parent in Vermont for about 25 years, and has been active in that time advocating for the rights of parents and children in the system. In 2016, she was even appointed to sit on a foster parent workgroup created by the Legislature, which pushed, among other reforms, that the state provide a two-pager to foster parents each time a child was placed in their care.

But while Rolland-Forkey is glad to receive that document, which is supposed to guarantee she’ll get at least some basic information about the child in her care, she never assumes it’ll be accurate or complete.

As Rolland-Forkey was speaking to a VTDigger reporter over the phone, she began inspecting the state paperwork that had come with a child who had recently been in her home. Under “allergies and dietary restrictions,” she said, someone had simply drawn a line, suggesting there were none to report.

“Actually, that child has an EpiPen,” Rolland-Forkey said, “and was allergic to all shellfish.”

She learned about the allergy from the child, who mentioned it in conversation about a week after arriving.

Rolland-Forkey and many advocates — including Vermont’s newly created independent ombudsman for child welfare — say such scenarios are not rare, and the culprit, in most cases, is clear: antiquated information technology systems serving the family services division at the Department for Children and Families.

Vermont’s state government is no stranger to IT woes. Amidst a pandemic-induced economic shutdown, for example, the state’s unemployment system crashed repeatedly and later exposed the Social Security numbers of thousands of Vermonters.

But the problems with the family services divisions’ IT systems nevertheless stand out — not only because of the age of the databases, but because of the stakes involved.

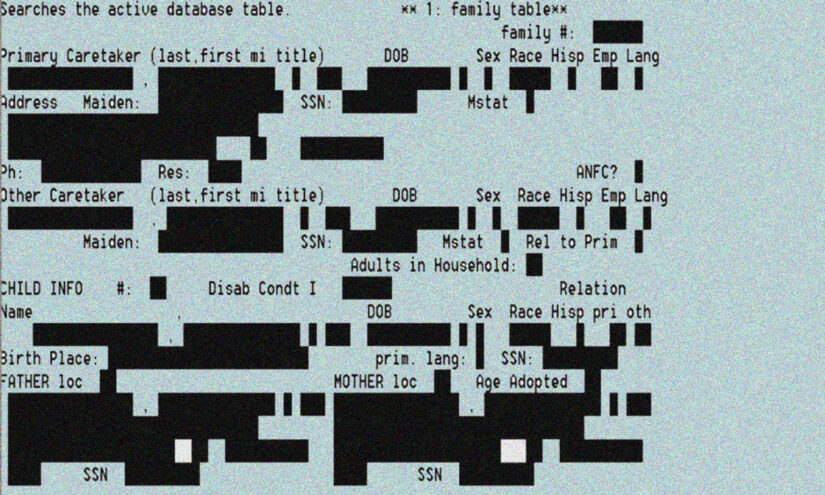

The primary system, called SSMIS, for inputting and warehousing basic information about minors in state custody and their placements was created in the early 1980s. State officials and advocates alike note frequently that this means the cyber backbone of Vermont’s child protection system predates the creation of the World Wide Web. A secondary system, FSDNet, that handles child abuse reporting intake information and case notes, dates back to the 1990s.

Before becoming deputy advocate in Vermont’s new Office of the Child, Youth and Family Advocate, which has independent oversight powers over DCF, Lauren Higbee worked at the department for five years, and has firsthand experience with these data systems. She’s since developed a shorthand for conveying their limited functionality.

“It doesn’t even have the capability of using a mouse,” she said of SSMIS. “That’s how old it is.”

In her former role, Higbee oversaw residential licensing and special investigations at DCF. And she recalled how badly the system complicated her work.

“You can’t search by facility to see all the allegations attributed to one facility. Right? So I’m not getting the scope, the history, the issue of what happened, or has happened or allegedly happened in one facility,” she said. “Huge issue.”

SSMIS is so clunky that even the most basic information about a child can be hard to find. If they’re placed with a private service provider which may have several locations, for example, the system will only register that provider’s name — not the specific address where that particular child is located.

DCF Deputy Commissioner Aryka Radke, who helms the department’s family services division, argued that this doesn’t mean that the state doesn’t know the location of the children in its care. But she acknowledged that identifying where it has stored such information is sometimes difficult.

“The address could be in case notes, which means that it’s gonna be harder to find. Obviously, the worker has the address for the child, which means we need to contact the worker to get the information. Or the district director may have it. Or it’s in a paper file at the district office. Or it’s in the worker’s telephone,” she said. “So it’s not readily available sometimes, but it’s absolutely there.”

But for Matthew Bernstein, who leads Vermont’s Office of the Child, Youth and Family Advocate, information that’s hard to find is almost as bad as information that doesn’t exist — putting kids at risk.

“We don’t know what medications a kid is allergic to,” he said. “A kid is in the hospital having an acute event — and sure, medical providers can do their thing and sure, some DCF workers can shuffle around looking for some paper that says what medications the kid is allergic to or anything else relevant to that. But that information is not at our fingertips. And that can obviously be catastrophic.”

As work-arounds to these inadequate systems, state workers and administrators report that they rely on an unwieldy and rickety system of supplemental databases, their own memories, and more than 30 Excel spreadsheets. The result is redundant data entry which is time consuming and, most importantly, vulnerable to human error.

“When we remove a child and take them into state custody, we’re really taking responsibility for them and all that that entails,” said Amy Rose, the policy director for the nonprofit advocacy group Voices for Vermont’s Children. “And not prioritizing just even accurate information — or the ability to access that information — really sets us all up for mistakes. And those mistakes can have a significant impact on the lives of the children that we’re taking responsibility for.”

A report on the drivers behind the high rates of children in state custody in Vermont, produced by researchers at the University of Vermont two years ago, named the “immediate priority” of replacing the division’s IT infrastructure as its first recommendation.

The researchers found that data systems were inadequate and did not allow child welfare workers to “meaningfully measure and track child safety, permanency, or wellbeing.” Bad data impacted decision-making, and created “opportunities for individual bias in decisions to place a child,” the study’s authors wrote.

In November 2021, Sally Borden, the co-chair of Vermont’s citizen advisory council to DCF, urged lawmakers in testimony to invest in a new IT infrastructure and marveled that the system wasn’t riddled with even more errors. She argued that the status quo makes the foster care system a sort of black box. Because family services databases cannot reliably search, organize, and collate data, administrators and advocates alike often find it impossible to accurately measure a problem — let alone measure progress in fixing it.

To figure out how many parents involved with DCF were dealing with substance use disorders, she noted, the department had recently relied on a hand count, derived from asking individual family services workers to tally up their cases.

“This, in the middle of an opioid crisis, is absurd,” Borden wrote.

In October 2020, Christine Johnson, then the head of DCF’s family services division, offered a similar critique during a webinar hosted by Voices for Vermont’s Children. Johnson recalled arriving at her job the year prior and, in an attempt to get a lay of the land, requested a variety of data points she believed would be available “with a few strokes” in a user-friendly dashboard.

“What I found very quickly was that we had a system that was built in 1982 — back when computers weren’t even really a thing,” she said.

Radke, Johnson’s successor, pushed back at the notion that the state’s IT system puts children at any risk. “I think it impacts my team and that they have to go the extra mile to make sure that we have the level of care that we need,” she said.

Nevertheless, she stressed that an upgrade was of utmost importance. And Radke has made more progress than any of her predecessors to fix the problem, although it is only a start: She is finalizing a request for proposals to build a new IT system, expected out this January.

But once contractors submit their offers, the state will have to decide whether it is willing to pay for an overhaul. No one knows yet what the price tag will be.

“At this point, based on our estimates of similarly situated states, we’re estimating that the cost could be anywhere between $35 and $40 million,” Radke said. “But of course we’ll have a much better idea when we get those responses.”

Luckily, the federal government will likely pay half the cost. And those pushing for a new system can also plausibly argue the upfront cost will pay for itself over time. The state leaves federal dollars on the table each year in reimbursable expenses because the data system regularly fails to comply with federal reporting requirements.

But even if the state fully commits to funding a new system, it’ll be years before a new one is in place. Radke guessed three — at a minimum.

In the meantime, state workers and families will have to keep making do.

Rolland-Forkey, the veteran foster parent, wonders whether that’s tenable — for her, for other foster parents, and particularly for the children they bring into their homes. She worries the system causes even more “fracturing” for children already dealing with such instability. And she struggles with a feeling of “moral injury,” when she realizes a kid in her care isn’t taking the medications they need, or missed a doctor’s appointment, court hearing, or after-school activity because there was no reliable record available for her to consult.

“We’re supposed to be doing no harm,” she said. “We don’t take an oath or anything, but I feel that. I feel like that’s what we should be.”

This story was originally published in VTDigger.

Support The 74’s year-end campaign. Make a tax-exempt donation now.

Vermont

Essex Junction teen dies in Beltline crash

BURLINGTON, Vt. (WCAX) – An Essex teen is dead following a crash on Burlington’s Beltline, also known as Route 127.

Burlington Police Chief Jon Murad says it happened just south of the North Avenue interchange on Route 127 at around 5:30 p.m.

He says an Audi was speeding going southbound when it crossed the median and struck a jeep. The driver of the Audi, 18-year-old Mark Omand of Essex Junction, was killed in the crash.

The person driving the Jeep, 45-year-old Derek Lorrain of Burlington, had to be extracted from the car by the fire department and was sent to the hospital.

No one else was involved in the crash.

There were also reports of power outages in Burlington’s New North End at around the same time, but it’s unconfirmed if it was related to or caused by this crash.

Copyright 2025 WCAX. All rights reserved.

Vermont

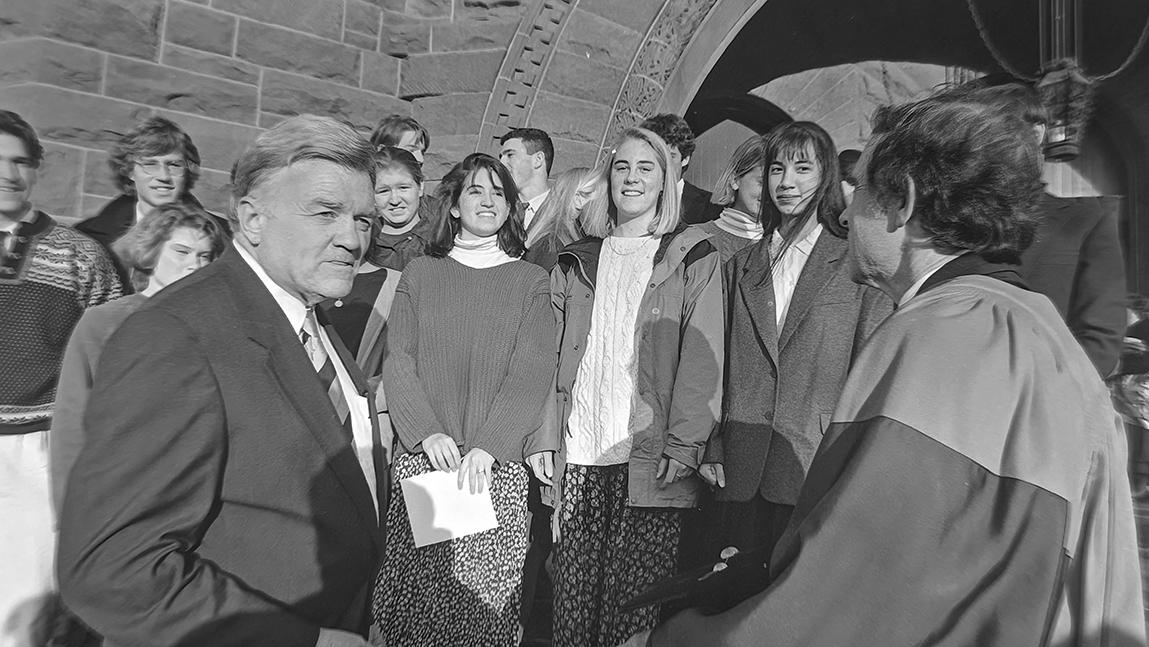

Former UVM President Thomas P. Salmon Dies at 92

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, in1932, Salmon was raised in…

Vermont

‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’ is set at a fictional Vermont college. Where is it filmed?

The most anticipated TV shows of 2025

USA TODAY TV critic Kelly Lawler shares her top 5 TV shows she is most excited for this year

It’s time to hit the books: one of Vermont’s most popular colleges may be one that doesn’t exist.

The Jan. 15 New York Times mini crossword game hinted at a fictional Vermont college that’s used as the setting of the show “The Sex Lives of College Girls.”

The show, which was co-created by New Englander Mindy Kaling, follows a group of women in college as they navigate relationships, school and adulthood.

“The Sex Lives of College Girls” first premiered on Max, formerly HBO Max, in 2021. Its third season was released in November 2024.

Here’s what to know about the show’s fictional setting.

What is the fictional college in ‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’?

“The Sex Lives of College Girls” takes place at a fictional prestigious college in Vermont called Essex College.

According to Vulture, Essex College was developed by the show’s co-creators, Kaling and Justin Noble, based on real colleges like their respective alma maters, Dartmouth College and Yale University.

“Right before COVID hit, we planned a research trip to the East Coast and set meetings with all these different groups of young women at these colleges and chatted about what their experiences were,” Noble told the outlet in 2021.

Kaling also said in an interview with Parade that she and Noble ventured to their alma maters because they “both, in some ways, fit this East Coast story” that is depicted in the show.

Where is ‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’ filmed?

Although “The Sex Lives of College Girls” features a New England college, the show wasn’t filmed in the area.

The show’s first season was filmed in Los Angeles, while some of the campus scenes were shot at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. The second season was partially filmed at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

Science4 days ago

Science4 days agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLas Vegas police release ChatGPT logs from the suspect in the Cybertruck explosion

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoMichael J. Fox honored with Presidential Medal of Freedom for Parkinson’s research efforts

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: Millennials try to buy-in or opt-out of the “American Meltdown”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPhotos: Pacific Palisades Wildfire Engulfs Homes in an L.A. Neighborhood

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrial Starts for Nicolas Sarkozy in Libya Election Case