Vermont

Vermont experts offer guidance for bringing birds, not bears, to the feeder

The Vermont Fish & Wildlife Division is recommending that Vermonters wait till the start of December to place up their fowl feeders to keep away from attracting bears.

Though fowl feeding is an thrilling solution to rise up shut and private with the neighborhood chickadees and cardinals, Doug Morin, Vermont Fish & Wildlife’s fowl challenge chief, stated that feeders aren’t important to serving to birds survive the winter. As such, folks ought to keep away from the temptation to place feeders outdoors till bears have begun to hibernate.

Morin additionally famous that if folks see a bear throughout its dormant interval — from December to April — they need to take down their fowl feeders for at the least one week. If a bear isn’t capable of finding meals, will probably be extra prone to return to its winter den.

“Folks ought to do all the things they’ll to forestall a bear from discovering meals at their dwelling, as a result of as soon as this occurs the bear might return for years persevering with to verify for meals,” Jaclyn Comeau, Vermont Fish & Wildlife’s wildlife biologist and black bear challenge chief, wrote in an e-mail to VTDigger.

Comeau stated that if Vermonters have a “continual historical past with (bears) foraging of their yard,” they need to wait till there’s at the least a foot of snow on the bottom earlier than placing a fowl feeder outdoors.

“Traditionally, bears are identified to return out of their hibernation throughout heat intervals within the winter. So it isn’t loopy for those who see a bear in January,” Morin stated.

Bear sightings throughout dormancy, nevertheless, are taking place extra typically, in keeping with Morin, partially on account of warming temperatures from the results of local weather change.

Whereas Vermonters will seemingly see the identical solid of avian characters at their feeders this yr, local weather change can be affecting migratory patterns among the many state’s fowl populations.

It has induced some birds to fly “farther and farther north” in Vermont through the spring and summertime, Morin stated.

A lot of the roughly 300 species of birds which were recorded in Vermont are migratory, he famous. For instance, bobolinks, which Morin characterised as some of the “charismatic grassland birds” in Vermont, elevate their younger in the summertime whereas there are sufficient bugs to feed on after which fly hundreds of miles to the southernmost tip of South America through the winter. They are often recognized by their white and black tuxedo or their music, generally in comparison with the sounds of R2-D2 from Star Wars.

Ruby-throated hummingbirds, which weigh the identical as about two nickels, fly a nonstop, multiple-day journey straight throughout the Gulf of Mexico earlier than returning to Vermont.

Different birds, corresponding to jap bluebirds or American robins, are short-distance migratory birds, which means they are going to transfer simply as far south as they must. They could keep in Vermont year-round or journey to southern New England or down the Atlantic.

There’s additionally the chance of birds “transferring out” of Vermont on account of habitat loss, Morin stated. He talked about the Bicknell’s thrush, which nests within the state’s high-elevation forests, noting that if bushes grow to be depleted there shall be “no place for these species to nest.”

Alexandra Kosiba, assistant professor of forestry on the College of Vermont Extension, stated that hotter temperatures introduced on by local weather change might trigger higher-elevation forests to grow to be much less populated.

She cautioned, nevertheless, that it’s difficult to foretell how local weather change will in the end have an effect on bushes, particularly as a result of forests are “extremely resilient.” She stated that it’s going to in the end rely on which bushes are in a position to adapt and the way profitable regeneration is likely to be.

Morin additionally worries about how local weather change will have an effect on birds’ meals sources.

“What we’re seeing is domestically, bugs might begin popping out of their winter dormancy earlier, whereas the birds might arrive later. So you possibly can have this disjunction between pure occasions. And we’re not completely positive how which will have an effect on issues,” Morin stated.

Some measures that Vermonters can take to assist fowl populations embrace putting feeders nearer than 4 ft or farther than 10 ft from a window to be able to scale back fowl collisions. Morin additionally recommends cleansing fowl feeders each few weeks to remove dangerous micro organism and viruses and protecting cats — the main explanation for fowl deaths in North America — inside.

He famous that planting native vegetation as an alternative of non-native invasive vegetation is necessary to supply a flourishing habitat for bugs, which in the end helps feed birds.

Correction: An earlier model of this story misrendered a citation from Jaclyn Comeau.

Do not miss a factor. Join right here to get VTDigger’s weekly e-mail on the vitality business and the atmosphere.

Do you know VTDigger is a nonprofit?

Our journalism is made doable by member donations from readers such as you. If you happen to worth what we do, please contribute throughout our annual fund drive and ship 10 meals to the Vermont Foodbank if you do.

Vermont

Former UVM President Thomas P. Salmon Dies at 92

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, in1932, Salmon was raised in…

Vermont

‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’ is set at a fictional Vermont college. Where is it filmed?

The most anticipated TV shows of 2025

USA TODAY TV critic Kelly Lawler shares her top 5 TV shows she is most excited for this year

It’s time to hit the books: one of Vermont’s most popular colleges may be one that doesn’t exist.

The Jan. 15 New York Times mini crossword game hinted at a fictional Vermont college that’s used as the setting of the show “The Sex Lives of College Girls.”

The show, which was co-created by New Englander Mindy Kaling, follows a group of women in college as they navigate relationships, school and adulthood.

“The Sex Lives of College Girls” first premiered on Max, formerly HBO Max, in 2021. Its third season was released in November 2024.

Here’s what to know about the show’s fictional setting.

What is the fictional college in ‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’?

“The Sex Lives of College Girls” takes place at a fictional prestigious college in Vermont called Essex College.

According to Vulture, Essex College was developed by the show’s co-creators, Kaling and Justin Noble, based on real colleges like their respective alma maters, Dartmouth College and Yale University.

“Right before COVID hit, we planned a research trip to the East Coast and set meetings with all these different groups of young women at these colleges and chatted about what their experiences were,” Noble told the outlet in 2021.

Kaling also said in an interview with Parade that she and Noble ventured to their alma maters because they “both, in some ways, fit this East Coast story” that is depicted in the show.

Where is ‘The Sex Lives of College Girls’ filmed?

Although “The Sex Lives of College Girls” features a New England college, the show wasn’t filmed in the area.

The show’s first season was filmed in Los Angeles, while some of the campus scenes were shot at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. The second season was partially filmed at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.

Vermont

Tom Salmon, governor behind ‘the biggest political upset in Vermont history,’ dies at 92 – VTDigger

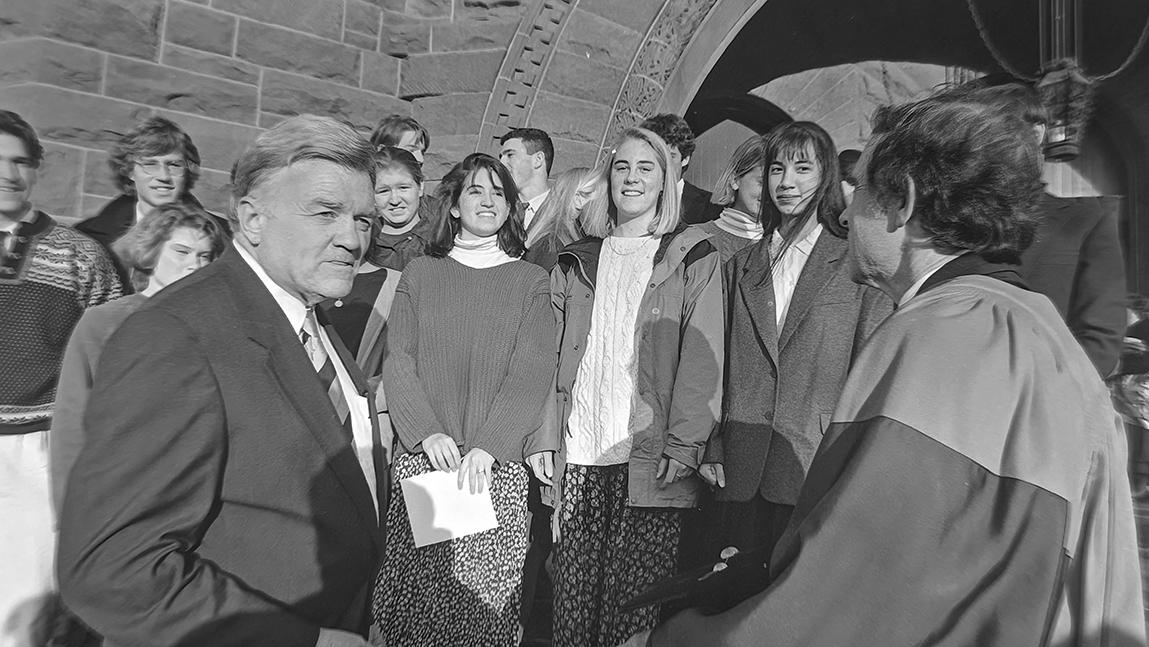

When Vermont Democrats lacked a gubernatorial candidate the afternoon of the primary deadline in August 1972, Rockingham lawyer Tom Salmon, in the most last-minute of Hail Mary passes, threw his hat in the ring.

“There could be a whale of a big surprise,” Salmon was quoted as saying by skeptical reporters who knew the former local legislator had been soundly beached in his first try for state office two years earlier.

Then a Moby Dick of a shock came on Election Day, spurring the Burlington Free Press to deem Salmon’s Nov. 7, 1972, victory over the now late Republican businessman Luther “Fred” Hackett “the biggest political upset in Vermont history.”

Salmon, who served two terms as governor, continued to defy the odds in subsequent decades, be it by overcoming a losing 1976 U.S. Senate bid to become president of the University of Vermont, or by entering a Brattleboro convalescent home in 2022, only to confound doctors by living nearly three more years until his death Tuesday.

Salmon, surrounded by family, died just before sundown at the Pine Heights Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation at age 92, his children announced shortly after.

“Your man Winston Churchill always said, ‘Never, never, never, never give up,” Salmon’s son, former state Auditor Thomas M. Salmon, recalled telling his father in his last days, “and Dad, you’ve demonstrated that.”

Born in the Midwest and raised in Massachusetts, Thomas P. Salmon graduated from Boston College Law School before moving to Rockingham in 1958 to work as an attorney, a municipal judge from 1963 to 1965, and a state representative from 1965 to 1971.

Salmon capped his legislative tenure as House minority leader. But his political career hit a wall in 1970 when he lost a race for attorney general by 17 points to incumbent Jim Jeffords, the now late maverick Republican who’d go on to serve in the U.S. House and Senate before his seismic 2001 party switch.

Vermont had made national news in 1962 when the now late Philip Hoff became the first Democrat to win popular election as governor since the founding of the Republican Party in 1854. But the GOP had a vise-grip on the rest of the ballot, held two-thirds of all seats in the Legislature and took back the executive chamber when the now deceased insurance executive Deane Davis won after Hoff stepped down in 1968.

As Republican President Richard Nixon campaigned for reelection in 1972, Democrats were split over whether to support former Vice President Hubert Humphrey or U.S. senators George McGovern or Edmund Muskie. The Vermont party was so divided, it couldn’t field a full slate of aspirants to run for state office.

“The reason that we can’t get candidates this year is that people don’t want to get caught in the struggle,” Hoff told reporters at the time. “The right kind of Democrat could have a good chance for the governorship this year, but we have yet to see him.”

Enter Salmon. Two years after his trouncing, he had every reason not to run again. Then he attended the Miami presidential convention that nominated McGovern.

“I listened to the leadership of the Democratic Party committed to tilting at windmills against what seemed to be the almost certain reelection of President Nixon,” Salmon recalled in a 1989 PBS interview with journalist Chris Graff. “That very night I made up my mind I was going to make the effort despite the odds.”

Before Vermont moved its primaries to August in 2010, party voting took place in September. That’s why Salmon could wait until hours before the Aug. 2, 1972, filing deadline to place his name on the ballot.

“Most Democratic leaders conceded that Salmon’s chances of nailing down the state’s top job are quite dim,” wrote the Rutland Herald and Times Argus, reporting that Salmon was favored by no more than 18% of those surveyed.

(Gov. Davis’ preferred successor, Hackett, was the front-runner. A then-unknown Liberty Union Party candidate — Bernie Sanders — rounded out the race.)

“We agreed that there was no chance of our winning the election unless the campaign stood for something,” Salmon said in his 1989 PBS interview. “Namely, addressed real issues that people in Vermont cared about.”

Salmon proposed to support average residents by reforming the property tax and restricting unplanned development, offering the motto “Vermont is not for sale.” In contrast, his Republican opponent called for repealing the state’s then-new litter-decreasing bottle-deposit law, while a Rutland County representative to the GOP’s National Committee, Roland Seward, told reporters, “What are we saving the environment for, the animals?”

As Republicans crowded into a Montpelier ballroom on election night, Salmon stayed home in the Rockingham village of Bellows Falls — the better to watch his then 9-year-old namesake son join a dozen friends in breaking a garage window during an impromptu football game, the press would report.

At 10:20 p.m., CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite interrupted news of a Nixon landslide to announce, “It looks like there’s an upset in the making in Vermont.”

The Rutland Herald and Times Argus summed up Salmon’s “winning combination” (he scored 56% of the vote) as “the image of an underdog fighting ‘the machine’” and “an appeal to the pocketbook on taxes and electric power.”

Outgoing Gov. Davis would later write in his autobiography that the Democrat was “an extremely intelligent, articulate, handsome individual with loads of charm.”

“Salmon accepted a challenge which several other Democrats had turned down,” the Free Press added in an unusual front-page editorial of congratulations. “He then accomplished what almost all observers saw as a virtual impossibility.”

As governor, Salmon pushed for the prohibition of phosphates in state waters and the formation of the Agency of Transportation. Stepping down after four years to run for U.S. Senate in 1976, he was defeated by incumbent Republican Robert Stafford, the now late namesake of the Stafford federal guaranteed student loan program.

Salmon went on to serve as president of the University of Vermont and chair of the board of Green Mountain Power. In his 1977 gubernatorial farewell address, he summed up his challenges — and said he had no regrets.

“A friend asked me the other day if it was all worth it,” Salmon said. “Wasn’t I owed more than I received with the energy crisis, Watergate, inflation, recession, natural disasters, no money, no snow, a tax revolt, and the anxiety of our people over government’s capacity to respond to their needs? My answer was this: I came to this state in 1958 with barely enough money in my pocket to pay for an overnight room. In 14 short years I became governor. The people of Vermont owe me nothing. I owe them everything for the privilege of serving two terms in the highest office Vermont can confer on one of its citizens.”

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

Science4 days ago

Science4 days agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLas Vegas police release ChatGPT logs from the suspect in the Cybertruck explosion

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoMichael J. Fox honored with Presidential Medal of Freedom for Parkinson’s research efforts

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: Millennials try to buy-in or opt-out of the “American Meltdown”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPhotos: Pacific Palisades Wildfire Engulfs Homes in an L.A. Neighborhood

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrial Starts for Nicolas Sarkozy in Libya Election Case