Lifestyle

Boulders Crush Cars in Horrific Peruvian Rockslide Caught on Camera

An absolutely horrific natural disaster went down in South America this weekend that saw two vehicles get completely crushed in a rockslide … which, somehow, didn’t claim any lives.

Two drivers in San Mateo, Peru were cruising along a highway in the middle of a mountain range … when, all of a sudden, a rockslide occurred — with a handful of massive boulders descending at full speed and making contact with the cars down below.

The video’s wild — you see a truck up ahead of the one that’s recording from its dashcam, and it gets flattened/tossed by a boulder. Not long after … the truck recording also gets hit.

Per CNN … both drivers survived the ordeal, although it’s unclear if they sustained injuries.

What makes that even more shocking is when you see what this nightmare looked like from the inside. The driver of the truck with the dash cam footage had another angle showing himself fleeing … and he narrowly escaped getting squashed, if only by seconds/inches.

There are pics circulating of the aftermath from this … and it gives you a full sense of how many rocks ended up coming down the mountainside, and how destructive this really was.

As you can see … the entire highway ended up being blocked by boulders and debris, and first responders were on the scene trying to clear the road as best as they could. According to reports, it took about four hours for them to get the flow of traffic moving again.

As for what may have caused this … authorities suspect heavy rain possibly destabilized some of the terrain there. That’s something folks here in SoCal can relate to these days.

It’s a miracle nobody died from this … drive safe, everyone.

Lifestyle

‘Evil Dead’ Star Bruce Campbell Reveals He Has Cancer

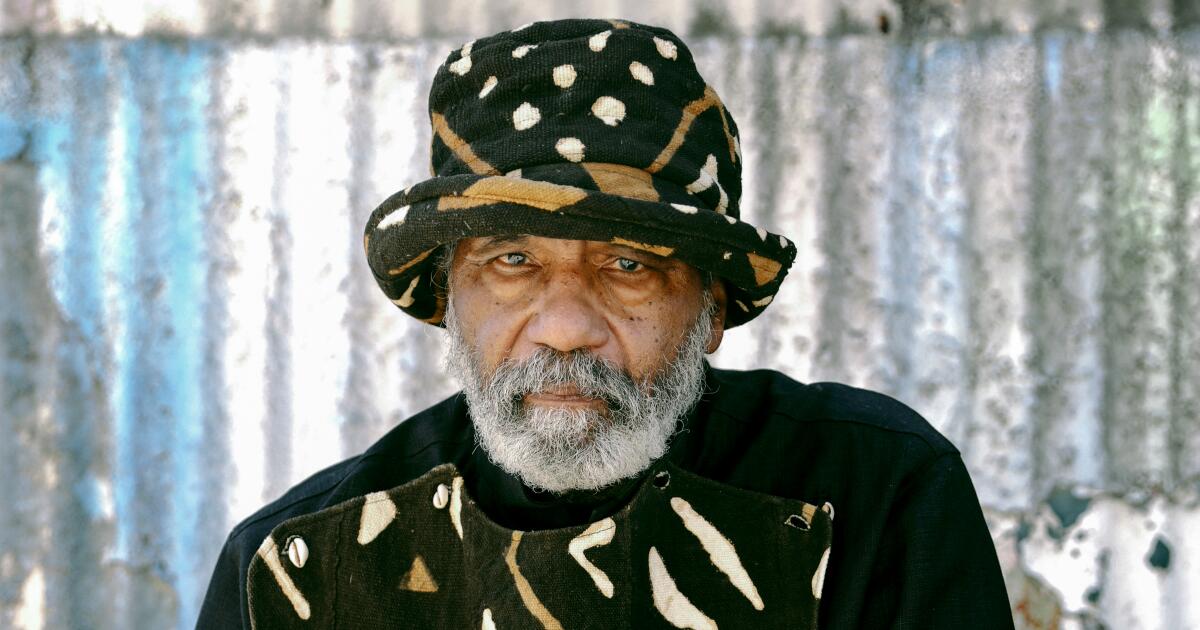

Bruce Campbell

I’m Battling Cancer

Published

Bruce Campbell has revealed he has cancer, but says it’s a type that’s treatable, though not curable.

“The Evil Dead” actor shared the news Monday in a message to fans, writing, “Hi folks, these days, when someone is having a health issue, it’s referred to as an ‘opportunity,’ so let’s go with that — I’m having one of those.” He continued, “It’s also called a type of cancer that’s ‘treatable’ not ‘curable.’ I apologize if that’s a shock — it was to me too.”

Campbell said he wouldn’t go into further detail about his diagnosis, but explained his work schedule will be changing. “Appearances and cons and work in general need to take back seat to treatment,” he wrote, adding he plans to focus on getting “as well as I possibly can over the summer.”

As a result, Campbell says he has to cancel several convention appearances this summer, noting, “Treatment needs and professional obligations don’t always go hand-in-hand.”

He says his plan is to tour this fall in support of his new film, “Ernie & Emma,” which he stars in and directs.

Ending on a determined note, Campbell told fans, “I am a tough old son-of-a-bitch … and I expect to be around a while.”

Lifestyle

‘Scream 7’ takes a weak stab at continuing the franchise : Pop Culture Happy Hour

Neve Campbell in Scream 7.

Paramount Pictures

hide caption

toggle caption

Paramount Pictures

The OG Scream Queen Neve Campbell returns. Scream 7 re-centers the franchise back on Sidney Prescott. She has a new life, a family, and lots of baggage. You know the drill: Someone dressing up as the masked slasher Ghostface comes for her, her family and friends. There’s lots of stabbing and murder and so many red herrings it’s practically a smorgasbord.

Follow Pop Culture Happy Hour on Letterboxd at letterboxd.com/nprpopculture

Lifestyle

Smoke a joint and get deep with flowers at this guided floral design workshop in DTLA

Abriana Vicioso is the host of the Flower Hour, which takes place monthly.

(Jennifer McCord / For The Times)

Each flower carries a personal history. For Abriana Vicioso, the calla lily was her parents’ wedding flower — a symbol of her mother’s beauty. “She had this big, beautiful white calla lily in her hair,” Vicioso says. “I love my parents. They’re the reason I’m here. I’ll never forget where I came from.”

The Flower Hour begins with Vicioso announcing, with a warm smile: “Today is about touching grass.” The florist-by-trade gestures behind her to hundreds of flowers contained in buckets — blue thistles, ivory anemones and calla lilies painted silver — all twisted and unfurling into the air. “Tonight is going to be so sweet and intimate,” Vicioso says, eyeing the beautiful chaos at her feet. A grin buds across her face.

Moments before the workshop, participants sit at candlelit tables exchanging horoscopes and comparing their favorite flowers. A mention of the illustrious bird-of-paradise flower elicits coos and awe from the women. Izamar Vazquez, who is from Jalisco, Mexico, reveals her fondness for roses, which make her feel connected to her Mexican roots.

Vicioso hosts her flower-themed wellness workshop near the iconic Original Los Angeles Flower Market in downtown L.A. In January, the first Flower Hour event sold out, prompting her to make it a monthly series. Vicioso describes the event as a “three-part journey” where participants are invited to drink herbal tea, smoke rose-petal-rolled cannabis joints and create a floral arrangement. “The guide is to connect with the medicine of flowers,” Vicioso says.

Rose petal joints, tea and flower arranging are all part of The Flower Hour event’s offerings.

The event is hosted at the Art Club, a membership-based co-working space. “The Flower Hour is really beautiful. Everyone gets to explore their creativity while meeting new people,” says Lindsay Williams, the co-owner of the Art Club.

The idea for Flower Hour came to Vicioso during a conversation with her mother. “We joke all the time that flowers were destined to make their way into my life,” she says. She works as a florist and models on the side, even appearing in the pages of Vogue. Vicioso grew up in a Caribbean household, where flowers and offerings were part of daily life. “In my culture and religion, a lot of my family practices — an Afro-Caribbean religion — we build altars.”

Like many cultures, flowers carry sentimental value in her religion. “I’m Caribbean, so a lot of my family practices a Yoruba religion, which comes from Africa. In the Caribbean, it’s well known as Santería.”

-

Share via

After a difficult year and a breakup, Vicioso wanted to marry her love of flowers with community building. Because Vicioso uses cannabis medicinally, the workshop naturally includes a smoking component. “My family has smoked cannabis for a lot of reasons for a long time. It’s a really healing plant,” she explains.

In the workshop, even the cannabis gets the floral treatment. Vicioso presents her rose-petal-wrapped joints on a silver platter at each table. She rolled each by hand. “If you’ve never smoked a rose-petal-rolled joint, the difference with this is it’s going to have roses that have a slight tobacco effect,” she announces.

During the workshop, Vicioso stresses the importance of buying cannabis from local vendors. The cannabis provided was purchased from a Northern Californian vendor. The wellness workshop aims to reclaim the healing ritual of smoking cannabis. “This is a plant that has been commercialized,” Vicioso says. “There’s a lot of Black and Brown people who are in jail for this plant.”

The resulting workshop is what Vicioso describes as “an immersive wellness experience that is the intersection of wellness, creativity, community and an appreciation of flowers.” The workshop serves as a reminder to enjoy Earth’s innate beauty in the form of flowers — including cannabis. “It’s this gift that the universe gave us for free and that I have this deep connection with,” Vicioso says.

Conversation cards to generate discussion among participants (top, letf). The workshop serves as a “third space” for Angelenos to engage in tactile creativity and community building outside of traditional nightlife settings.

After enjoying lavender chamomile tea and smoking a joint, Vicioso introduces the flowers to the group before inviting them to pick their own. She emphasizes each flower’s personality traits, describing green dianthus as a “Dr. Seuss” plant. Then, there are calla lilies with their “main character moment.” It gets personal. “Start thinking of a flower in your life that you can discover,” she says. “If you’re feeling like you need inspiration, you can always remember that these flowers have stories.”

Vicioso infuses wisdom into her instruction on floral arrangements: There are no mistakes. Let the flowers tell you where they want to go, she urges. Intuition will be your guide — the wilder, the better.

“Hecho in Mexico” reads a sticker on a bunch of green stems. “Like me,” says Vazquez with a laugh. “They’re all doing their own thing. Like a family,” she says later, arranging stems.

The Flower Hour participants and Vicioso, center, chat as they build their own floral arrangements at the sold-out event.

Two participants — Vazquez and Rebeca Alvarado — are friends who run a floral design company together called Izza Rose. Like Vicioso, the friends have a connection to flowers through their Latin American culture. They met Vicioso in the floral industry and were overjoyed to discover her workshop.

“This is a great way to connect with other people,” says Vazquez.

Alvarado agrees, adding: “You’re getting to know people outside of going to bars. You can connect in different ways when there’s an activity.”

Vazquez uses flowers to stay connected to her Mexican heritage, adding that she prefers to support Mexican vendors. In recent months, the downtown L.A. flower market has struggled to recover from ongoing ICE raids. “Some are scared to come back,” says Vazquez.

Hand-rolled cannabis joints wrapped in rose petals are presented on a silver platter at The ArtClub (top, right). The Flower Hour aims to reclaim the healing rituals of cannabis and flowers.

Another participant, Barbara Rios, was attracted to the workshop for stress relief. “You can hang out with your friends, but it’s nice to do things with your hands,” she says. “I work a stressful job, and it’s nice to have that third space that we’re all craving.”

On this February night, the participants were predominantly women, save for one man. In the future, Vicioso hopes that more men learn to engage with flowers. “There’s a statistic about men receiving flowers for the first time at their funerals, and I think we have changed that,” she says.

To conclude the workshop, Vicioso encourages participants to build lasting friendships and incorporate flower arranging into their daily practice — even if it’s just with a small, inexpensive bouquet.

“Get some flowers together, go to the park, hang out with each other and hang out with me,” she says. Participants leave with flower arrangements in hand. In the darkness of the night air, it briefly looks as though the women carry silver calla lilies that are blooming from their palms.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts5 days ago

Massachusetts5 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO5 days ago

Denver, CO5 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWorld reacts as US top court limits Trump’s tariff powers