Entertainment

Review: Made by a solo Coen brother, 'Drive-Away Dolls' is trashy fun and exceedingly disposable

It’s fascinating that Ethan Coen and Tricia Cooke, longtime filmmaking collaborators and spouses, and the creative team behind the exploitation flick “Drive-Away Dolls,” have repeatedly — and lovingly — described their new film as “trashy” in interviews. It’s a way of nodding to influences like the “Pope of Trash” himself, John Waters, and titillating B-movie king Russ Meyer. Or perhaps it’s a way to get ahead of, and away from, certain expectations tied to Coen and his former filmmaking partner, his brother Joel. This ain’t your daddy’s “No Country for Old Men,” after all.

“Drive-Away Dolls” rather excitedly asserts a space that one could call “a country for young lesbians,” if one were so inclined. The film itself is a “queering” of the ’90s crime caper, the kind of sardonic, ironic, muscular and oh-so-masculine film that the Coen brothers and their contemporaries (Quentin Tarantino, Guy Ritchie, et al.), popularized some three decades ago, birthing generations of film bros.

Coen and Cooke wrote the film together and essentially co-directed, though only Coen is credited as the director, with Cooke as editor (she also edited “The Big Lebowski” and “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” with the brothers). The script, written some 20-odd years ago, originated from Cooke’s queer youth in New York City’s lesbian bars and has been sitting on the back burner for years. The 1999 setting of these events is at once a reflection of the script’s age, and an inadvertent throwback to the kinds of movies it references. With its rapid-fire deadpan dialogue, low canted angles, detached, ironic violence and kooky transitional wipes, it feels self-consciously retro, even if it was, at one time, intended to be contemporary.

The plot centers around an odd couple of friends: Jamie (Margaret Qualley), an amorous lesbian Lothario, and Marian (Geraldine Viswanathan), a buttoned-up office worker, who decide to drive to Tallahassee, Fla., when Jamie catches too much heat for cheating on her cop ex, Sukie (Beanie Feldstein). The friends opt for a cheap “drive-away” rental car and are accidentally given a vehicle with a secret stash in the trunk, sparking a chase across state lines involving a senatorial sex scandal. And though they’ve got two bumbling henchmen in pursuit, these gal pals live, laugh and lady-love their way through every sapphic saloon south of the Mason-Dixon line.

From left, Geraldine Viswanathan, Margaret Qualley and Beanie Feldstein in the movie “Drive-Away Dolls.”

(Wilson Webb / Working Title / Focus Features)

It’s “Pulp Fiction” with dildos, and it’s unabashedly horny and female pleasure-centric. Yet, one can’t ignore the nagging sense, at times, that “Drive-Away Dolls” just feels like the lesbian porn parody of a dude-heavy crime comedy. A basement make-out party hosted by a women’s soccer team is just a little too far-fetched, but then again, so is the supremely silly sex scandal that animates the entire plot. The film is often crude in a way that’s cringe-worthy, but it’s also stacked with jokes and moves at such a brisk pace (it’s barely 85 minutes) that it’s over before you know what hit you.

Qualley and Viswanathan are fantastically committed and charismatic, with the former demonstrating a capacity for broad comedy. Viswanathan is lethally precise in her line deliveries. But open the hood of the story and it turns out this beater is a lemon: The mechanics of the plot simply aren’t there. How or even why are these two friends? Colman Domingo growls appealingly as some sort of crime boss, but who is his character? What are the stakes of this scandal and why should we care? Does plot device A insert into story element B? Maybe not, and maybe no one cares if this jumble of amusing parts makes a coherent whole.

The slight and scanty “Drive-Away Dolls” could dissipate with a gust of wind, but it beats a hasty getaway before that becomes a problem. While its story fails to justify its own existence, it delivers what it says on the tin: dumb, randy fun, even if that feels retrograde in more ways than one.

Katie Walsh is a Tribune News Service film critic.

‘Drive-Away Dolls’

Rating: R, for crude sexual content, full nudity, language and some violent content

Running time: 1hour, 24 minutes

Playing: In wide release Friday, Feb. 23

Movie Reviews

‘Hoppers’ review: Who can argue with hilarious talking animals?

Just when you think Pixar’s petting-zoo cute new movie “Hoppers” is flagrantly ripping off James Cameron, the characters come clean.

movie review

HOPPERS

Running time: 105 minutes. Rated PG (action/peril, some scary images and mild language). In theaters March 6.

“You guys, this is like ‘Avatar’!,” squeals 19-year-old Mabel (Piper Curda), the studio’s rare college-age heroine.

Shoots back her nutty professor, Dr. Fairfax (Kathy Kajimy): “This is nothing like ‘Avatar!’”

Sorry, Doc, it definitely is. And that’s fine. Placing the smart sci-fi story atop an animated family film feels right for Pixar, which has long fused the technological, the fantastical and the natural into a warm signature blend. Also, come on, “Avatar” is “Dances With Wolves” via “E.T.”

What separates “Hoppers” from the pack of recent Pix flix, which have been wholesome as a church bake sale, is its comic irreverence.

Director Daniel Chong’s original movie is terribly funny, and often in an unfamiliar, warped way for the cerebral and mushy studio. For example, I’ve never witnessed so many speaking characters be killed off in a Pixar movie — and laughed heartily at their offings to boot.

What’s the parallel to Pandora? Mabel, a budding environmental activist, has stumbled on a secret laboratory where her kooky teachers can beam their minds into realistic robot animals in order to study them. They call the devices “hoppers.”

Bold and fiery Mabel — PETA, but palatable — sees an opportunity.

The mayor of Beaverton, Jerry (Jon Hamm), plans to destroy her beloved local pond that’s teeming with wildlife to build an expressway. And the only thing stopping the egomaniacal pol — a more upbeat version of President Business from “The Lego Movie” — is the water’s critters, who have all mysteriously disappeared.

So, Mabel avatars into beaver-bot, and sets off in search of the lost creatures to discover why they’ve left.

From there, the movie written by Jesse Andrews (“Luca”) toys with “Toy Story.” Here’s what mischief fuzzy mammals, birds, reptiles and insects get up to when humans aren’t snooping around. Dance aerobics, it turns out.

Per the usual, “Hoppers” goes deep inside their intricate society. The beasts have a formal political system of antagonistic “Game of Thrones”-like royal houses. The most menacing are the Insect Queen (Meryl Streep — I’d call her a chameleon, but she’s playing a bug), a staunch monarch butterfly and her conniving caterpillar kid (Dave Franco). They’re scheming for power.

Perfectly content with his station is Mabel’s new best furry friend King George (Bobby Moynihan), a gullible beaver who ascended to the throne unexpectedly. He happily enforces “pond rules,” such as, “When you gotta eat, eat.”

That means predators have free rein to nosh on prey, and everybody’s cool with it. Because of bone-dry deliveries, like exhausted office drones, the four-legged cast members are hilarious as they go about their Animal Planet activities.

No surprise — talking lizards, sharks, bears, geese and frogs are the real stars here. They far outshine Mabel, even when she dons beaver attire. Much like a 19-year-old in a job interview, she doesn’t leave much of an impression.

Yes, the teen has a heartfelt motivation: The embattled pond was her late grandma’s favorite place. Mabel promised her that she’d protect it.

But in personality she doesn’t rank as one of Pixar’s most engaging leads, perhaps because she’s past voting age. Mabel is nestled in a nebulous phase between teenage rebellion and adulthood that’s pretty blasé, even if a touch of tension comes from her hiding her Homo sapien identity from her new diminutive pals. When animated, kids make better adventurers, plain and simple.

“Hoppers” continues Pixar’s run of humble, charming originals (“Luca,” “Elio”) in between billion-dollar-grossing, idea-starved sequels (“Inside Out 2,” probably “Toy Story 5”). The Disney-owned studio’s days of irrepressible innovation and unmatched imagination are well behind it. No one’s awed by anything anymore. “Coco,” almost 10 years ago, was their last new property to wow on the scale of peak Pixar.

Look, the new movie is likable and has a brain, heart and ample laughs. That’s more than I can say for most family fare. “A Minecraft Movie” made me wanna hop right out of the theater.

Entertainment

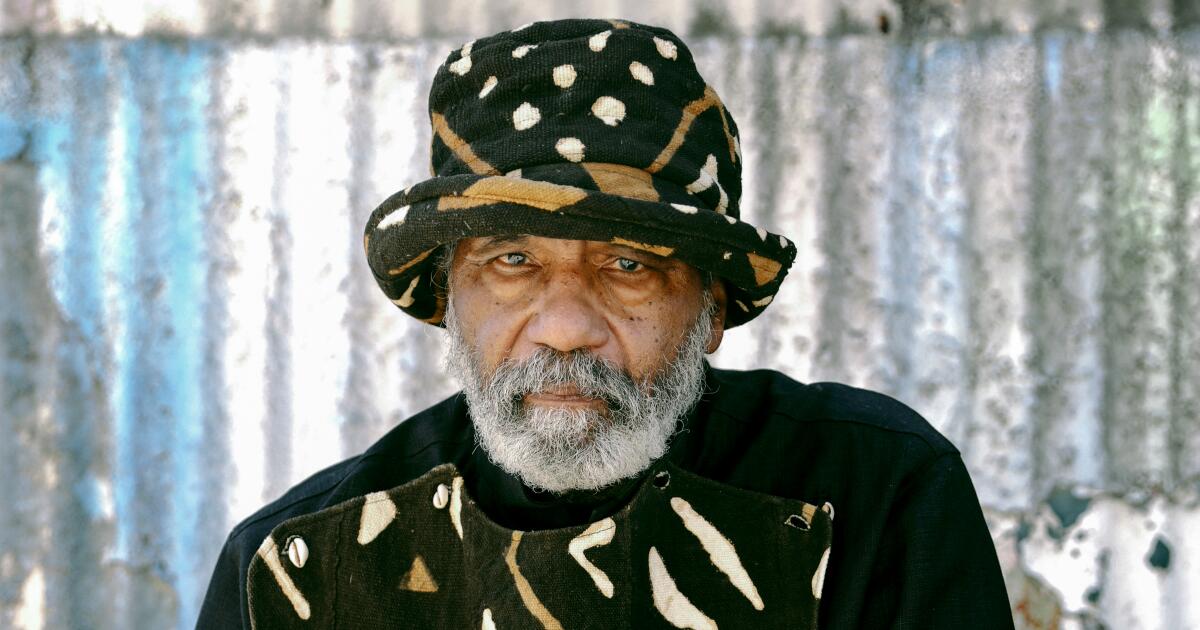

Ulysses Jenkins, Los Angeles artist and pioneer of Black experimental video, dies at 79

Ulysses Jenkins, the pioneering Los Angeles-born video artist whose avant-garde compositions embodied Black experimentalism, has died. He was 79.

Jenkins’ death was confirmed by his alma mater Otis College, where he studied under renowned painter and printmaker Charles White in the late 1970s and returned as an instructor years later. The Los Angeles art and design school shared a statement from the Charles White Archive, which said, “Jenkins had a profound impact on contemporary art and media practices.”

“A trailblazing figure in Black experimental video, he was widely recognized for works that used image, sound, and cultural iconography to examine representation, race, gender, ritual, history, and power,” the statement said.

A self-proclaimed “griot,” Jenkins throughout his decades-spanning career maintained an art practice grounded in the tradition of those West African oral historians who came before him. Through archival documentaries like “The Nomadics” and surrealist murals like “1848: Bandaide,” he leveraged alternative media to challenge Eurocentric representations of Black Americans in popular culture.

He was both an artist and a storyteller who sought to “reassert the history and the culture,” he told The Times in 2022. That year, the Hammer Museum presented Jenkins’ first major retrospective, “Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation.”

“Early video art was about the problems with the media that we are still having today: the notions of truth,” Jenkins said. “To that extent, early video art was a construct that was anti-media … a critical analysis of the media that we were viewing every night.”

Born in 1946 to Los Angeles transplants from the South, Jenkins was ambivalent about the city, which offered his parents some refuge from the blatant systemic racism they encountered in their hometowns, but housed an entertainment industry that had long perpetuated anti-Black sentiment.

“What Hollywood represents, especially in my work, is the classic plantation mentality,” Jenkins told The Times in 1986. “Although people aren’t necessarily enslaved by it, people enslave themselves to it because they’re told how fantastic it is to help manifest these illusions for a corporate sponsor.”

Jenkins, who participated in a group of artists committed to spontaneous action called Studio Z, was naturally drawn to video art over Hollywood filmmaking. “I can address any issue and I don’t have to wait for [the studios’] big OK. I thought this was a land of freedom, and video allows me that freedom and opportunity that I can create for myself and at least feel that part of being an American,” he said.

Jenkins went on to deconstruct Hollywood’s vision of the Black diaspora in experimental video compositions including “Mass of Images,” which incorporates clips from D.W. Griffith’s notoriously racist “The Birth of a Nation,” and “Two-Tone Transfer,” which depicts, in Jenkins’ words, a “dreamscape in which the dreamer awakens to a visitation of three minstrels who tell the story of the development of African American stereotypes in the American entertainment industry.”

Jenkins’ legacy is not only artistic but institutional, with the luminary having held teaching appointments at UCSD and UCI, where he co-founded the digital filmmaking minor with fellow Southern California-based artists Bruce Yonemoto and Bryan Jackson.

As artist and educator Suzanne Lacy penned in her social media tribute to Jenkins, which showed him speaking to students at REDCAT in L.A., “he has been an important part of our histories here in Southern California as video and performance artists evolved their practices.”

Movie Reviews

Review | Hoppers: Pixar’s new animation is a hilarious, heartfelt animal Avatar

4/5 stars

Bounding into cinemas just in time for spring, the latest Pixar animation is a pleasingly charming tale of man vs nature, with a bit of crazy robot tech thrown in.

The star of Hoppers is Mabel Tanaka (voiced by Piper Curda), a young animal-lover leading a one-girl protest over a freeway being built through the tranquil countryside near her hometown of Beaverton.

Because the freeway is the pet project of the town’s popular mayor, Jerry (Jon Hamm), who is vying for re-election, Mabel’s protests fall on deaf ears.

Everything changes when she stumbles upon top-secret research by her biology professor, Dr Sam Fairfax (Kathy Najimy), that allows for the human consciousness to be linked to robotic animals. This lets users get up close and personal with other species.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO5 days ago

Denver, CO5 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling