Entertainment

From Chris Isaak to Karen O, David Lynch's musical collaborators recount his strange, sonic mysticism

Back in 2013, David Lynch was in his home recording studio late one morning, surrounded by electric guitars of different shapes and colors. With effects pedals scattered at his feet, he opened a case with an orange sunburst lap-slide guitar inside. “This is the guitar that Ben Harper gave me,” Lynch said with a smile and genuine awe in his voice, dressed in a black suit jacket and shirt, gray hair piled high on top. “That thing makes a hell of a sound.”

The occasion was the coming release of his second solo album, “The Big Dream,” but it wasn’t the first or last time we talked about his music. He was a self-taught improviser on guitar, and a high school trumpeter, but he was drawn to any sounds that tapped meaningfully into feelings of heartache and tension, beauty and noise.

Over a half-century of work, he built a well-earned reputation as a surrealist auteur and master filmmaker. But Lynch, who died last week at 78, was equally passionate about other creative mediums, from painting and photography to designing furniture, and nothing held his imagination more powerfully than the music that filled his life and work.

We were in his fully equipped recording facility, called Asymmetrical Studio — built inside the house he once used as a location for his 1997 film “Lost Highway.” He spent a lot of his time there, and it was just one sign of his lifelong obsession with sound. It held an essential role in his life as a filmmaker and, eventually, a recording artist, songwriter and producer.

Angelo Badalamenti performs at the David Lynch Foundation Music Celebration at the Theatre at Ace Hotel in 2015.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / AP)

Lynch was a rare director with a recognizable musical aesthetic, created with the help of composer and close friend Angelo Badalamenti, among many others. He was attracted to smoky electric guitar twang and the most abrasive industrial sounds, and to rich female voices and lush layers of strings and organ. The through-line were sounds that leaned toward the smoldering and idiosyncratic — from his use of achingly passionate songs of heartbreak by Roy Orbison and Chris Isaak to his own shadowy recordings with modern torch singers Julee Cruise and Chrystabell.

Among his musical collaborators was Karen O, singer for the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, who appeared on his first solo album, 2011’s “Crazy Clown Time,” and remembers Lynch’s sound as tense and passionate. “There’s an eroticism, there’s an urgency, there’s mystery, there’s darkness, there’s the edginess, the rebellion,” she says. “All that is in David’s musical taste.”

They recorded an ominous, twangy, thunderous tune called “Pinky’s Dream,” featuring a breathless Karen O vocal. “I’ve never met a Pinky,” she says now with a laugh. “It’s a character that inhabits a David Lynch dreamscape. The music is chugging along and you just feel like you’re on one of those lost highways.”

“I guess I like it low and slow, but I also like so many kinds of music,” Lynch told me during a 2015 visit to the painting studio behind his home high up in the Hollywood Hills. “I love what sound can do, what music can do, and to marry to the picture and make the whole thing greater than the sum of the parts.”

As a director, he showed a gift for placing music with stunning impact, from Samuel Barber’s deeply emotional “Adagio For Strings” in 1980’s “The Elephant Man,” to the raging thrash metal riffs of Powermad in 1990’s “Wild at Heart,” and Rebekah Del Rio’s torrid Spanish a cappella reading of “Llorando” in “Mulholland Drive.”

In “Blue Velvet,” Lynch created an eerie moment of romance and nostalgia in an otherwise disturbing scene as actor Dean Stockwell, in paisley tuxedo jacket, lip-syncs Orbison’s 1963 hit “In Dreams.” The song’s use in the film helped spark an Orbison revival, and Lynch soon co-produced a new version of the song with the singer and T-Bone Burnett for a 1987 retrospective, “In Dreams: The Greatest Hits.”

That love of music ultimately led the director to begin dabbling in creating some of his own, starting with his distinctive collaborations with Badalamenti, which stretched from “Blue Velvet” in 1986 until the composer’s death in 2022. It was an especially close relationship between director and composer that Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran compares to Federico Fellini and Nino Rota, who scored all of the Italian filmmaker’s films from 1959 to 1979.

Likewise, Lynch and Badalamenti were “so closely linked that they almost can feel each other’s heartbeats,” says Rhodes, whose band of hitmakers also worked with Lynch on a few occasions, including his remixing two of their songs.

“I always say Angelo Badalamenti brought me into the world of music,” Lynch said. “I played the trumpet when I was young and I understand music, but I was in love with sound effects. So I wanted to build a studio to experiment with sound, but I knew I wasn’t a musician really. Angelo said, ‘David, I need lyrics.’ So I started writing lyrics for Angelo, and we worked together. And that was a combo — the David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti combo, and it brought out those things. That gave me more confidence.”

By the late 1980s, that impulse led the duo to Excalibur Sound Productions in New York City, where they worked on music with a young unknown singer, Julee Cruise, who had recorded their song “Mysteries of Love” for “Blue Velvet.” An album, 1989’s “Floating into the Night,” emerged after a year and a half of sessions, launching the single “Falling,” which had a second life as a theme for “Twin Peaks.”

In 2017, as the acclaimed third-season revival of “Twin Peaks” unfolded on Showtime, Cruise recalled to me the original directions from Lynch during her sessions. “He said, ‘Julee, you are a child full of wonder,’” said Cruise, who also performed the dreamy, mournful “The World Spins” on the series.

Julee Cruise sings the show’s theme song, “Falling,” in the pilot episode of “Twin Peaks.”

(CBS Photo Archive / Getty Images)

“I will always be known as this, and I will always be proud of this,” said Cruise, who died in 2022. Lynch also directed a one-hour musical film starring Cruise, “Industrial Symphony No. 1,” released in 1990 by Warner Bros. Records.

In subsequent years, Badalamenti was based in New Jersey, and made occasional trips to L.A. “Wherever we were, we would sit and make music,” Lynch said. Last year, the director expressed lasting sadness over the 2022 death of Badalamenti, who he called “my brother.”

“It just doesn’t seem possible that he’s gone,” Lynch said. “It just seems like I could call him up and we could make music again.”

In time, Lynch created multiple workspaces adjacent to his home in the Hollywood Hills: the recording studio, painting studio, wood shop and offices. He performed music live only one time, with his band Blue Bob in 2002, an experience he called “a traumatic thrill,” and something he wasn’t anxious to repeat.

“He wasn’t a musician. He couldn’t tell you, ‘I want an E minor here, and then I want to have eight bars of this,’” says Isaak, whose “Wicked Game” became a hit after appearing in 1990’s “Wild at Heart.” “We didn’t talk in that language.” Lynch went on to direct the music video for “Wicked Game.”

Aside from creating music alongside Lynch, Isaak appeared on camera in a prominent role in “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.” “I sure got lucky for how the stars aligned, that I got to work with him and hang with him and get to know him a little. I must have somebody up there looking over me because what a treat.”

Lynch was a filmmaker who treasured music enough to turn the Roadhouse bar in the 2017 season of “Twin Peaks” into a world-class nightclub, and included performances of complete songs in many episodes from the likes of Moby, Eddie Vedder and “The” Nine Inch Nails. In 1997, he’d recruited NIN’s Trent Reznor to create a soundscape for “Lost Highway,” and together they landed on the cover of Rolling Stone. (Lynch would later create a music video for NIN’s “Come Back Haunted.”)

Trent Reznor arrives at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 2019.

(Evan Agostini / Invision / AP)

Some collaborations were less expected but just as rewarding. In 2011, Duran Duran asked Lynch to direct the livestream of a concert from the Mayan Theater in Los Angeles, as part of the American Express “Unstaged” series that matched musicians with filmmakers. The result was fully in character, photographed in murky black-and-white for a worldwide online audience, and layered with Lynchian imagery and juxtapositions: smoke, fire, strange objects and dead animals superimposed over the band.

“When something magical like that happens, you embrace it as quickly as you can,” says Duran Duran’s Rhodes. “I just love his vision and the world that he creates. I knew that merging with Duran Duran would be something mad, something surreal and beautiful and extraordinary that nobody would’ve ever expected. I felt that he had the same intention with what he was making with us. It was an absolute joy.”

For several years, Lynch harnessed his musical connections to raise funds and awareness for the David Lynch Foundation, established to promote the benefits of Transcendental Meditation. He hosted a series of music and art events on both coasts, including his popular Festival of Disruption, and a 2009 benefit concert with former Beatles Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr at Radio City Music Hall.

On his next solo album, 2013’s “The Big Dream,” he recruited Swedish singer-songwriter Lykke Li soon after she relocated to Los Angeles. He handed her a coffee-stained note with a few lyrics jotted down and said, “Make this into a song.” She accepted Lynch’s note as “a clue, a puzzle, a question” toward something new. She recast his words “I’m waiting here” as the title of the aching bonus track “I’m Waiting Here.” Recording the track was unlike a normal session.

“I’ve never done that again with anyone else,” Lykke Li says now. “He stood next to me and it was almost like he directed me how to sing. It was almost like a seance. It was really based on feeling and intuition.”

Lykke Li also notes that Lynch “saved my life,” by introducing her then to Transcendental Meditation at a time when things were fast-moving and chaotic in her life. “It was like only when I started meditating that I really found a center and it’s unlocked everything for me,” she says.

A David Lynch photo of himself with singer Chrystabell, with whom he collaborated on his final musical project.

(David Lynch)

The final project Lynch finished and released before his death was “Cellophane Memories,” a collaboration with Chrystabell, recorded at his home in 2023 and 2024. Unlike the songs of romance from their previous work together, the record was marked by an experimental layering of vocals and other effects that eased it deeper into the avant-garde.

“We were both doing what we love to do, which is to experiment and to create,” Chrystabell says now, days after Lynch’s passing. “His mind was always alive, always inspired. There were always things brewing.”

Along the way, the duo recorded several other songs in different modes, including an unfinished project that was to be called “Strange Darling.” But the filmmaker-painter-musician was already looking to their next round of songs together.

“David loved a great pop song,” the singer recalls. “That was the next thing we were going to do. He was like, ‘Chrystabell, should we write some hits next time?’”

Instead, Lynch’s musical friends and collaborators have been in mourning this week, grateful for their moments together, diving back into the work he left. Chrystabell says she has dealt with her close friend’s death by listening to music left behind.

“So much of our music is really tailor-made for these moments,” she says, recalling Lynch lyrics like “the great unknown,” “angel star” and “10 trillion miles of dark.” “He was right there, and we explored that territory. Lyrics could be cute and fun backseat kind of sexy or cosmic, otherworldly, spiritual, almost hymnal music. I was marveling at that. It all hits different now.”

Movie Reviews

‘Hoppers’ review: Who can argue with hilarious talking animals?

Just when you think Pixar’s petting-zoo cute new movie “Hoppers” is flagrantly ripping off James Cameron, the characters come clean.

movie review

HOPPERS

Running time: 105 minutes. Rated PG (action/peril, some scary images and mild language). In theaters March 6.

“You guys, this is like ‘Avatar’!,” squeals 19-year-old Mabel (Piper Curda), the studio’s rare college-age heroine.

Shoots back her nutty professor, Dr. Fairfax (Kathy Kajimy): “This is nothing like ‘Avatar!’”

Sorry, Doc, it definitely is. And that’s fine. Placing the smart sci-fi story atop an animated family film feels right for Pixar, which has long fused the technological, the fantastical and the natural into a warm signature blend. Also, come on, “Avatar” is “Dances With Wolves” via “E.T.”

What separates “Hoppers” from the pack of recent Pix flix, which have been wholesome as a church bake sale, is its comic irreverence.

Director Daniel Chong’s original movie is terribly funny, and often in an unfamiliar, warped way for the cerebral and mushy studio. For example, I’ve never witnessed so many speaking characters be killed off in a Pixar movie — and laughed heartily at their offings to boot.

What’s the parallel to Pandora? Mabel, a budding environmental activist, has stumbled on a secret laboratory where her kooky teachers can beam their minds into realistic robot animals in order to study them. They call the devices “hoppers.”

Bold and fiery Mabel — PETA, but palatable — sees an opportunity.

The mayor of Beaverton, Jerry (Jon Hamm), plans to destroy her beloved local pond that’s teeming with wildlife to build an expressway. And the only thing stopping the egomaniacal pol — a more upbeat version of President Business from “The Lego Movie” — is the water’s critters, who have all mysteriously disappeared.

So, Mabel avatars into beaver-bot, and sets off in search of the lost creatures to discover why they’ve left.

From there, the movie written by Jesse Andrews (“Luca”) toys with “Toy Story.” Here’s what mischief fuzzy mammals, birds, reptiles and insects get up to when humans aren’t snooping around. Dance aerobics, it turns out.

Per the usual, “Hoppers” goes deep inside their intricate society. The beasts have a formal political system of antagonistic “Game of Thrones”-like royal houses. The most menacing are the Insect Queen (Meryl Streep — I’d call her a chameleon, but she’s playing a bug), a staunch monarch butterfly and her conniving caterpillar kid (Dave Franco). They’re scheming for power.

Perfectly content with his station is Mabel’s new best furry friend King George (Bobby Moynihan), a gullible beaver who ascended to the throne unexpectedly. He happily enforces “pond rules,” such as, “When you gotta eat, eat.”

That means predators have free rein to nosh on prey, and everybody’s cool with it. Because of bone-dry deliveries, like exhausted office drones, the four-legged cast members are hilarious as they go about their Animal Planet activities.

No surprise — talking lizards, sharks, bears, geese and frogs are the real stars here. They far outshine Mabel, even when she dons beaver attire. Much like a 19-year-old in a job interview, she doesn’t leave much of an impression.

Yes, the teen has a heartfelt motivation: The embattled pond was her late grandma’s favorite place. Mabel promised her that she’d protect it.

But in personality she doesn’t rank as one of Pixar’s most engaging leads, perhaps because she’s past voting age. Mabel is nestled in a nebulous phase between teenage rebellion and adulthood that’s pretty blasé, even if a touch of tension comes from her hiding her Homo sapien identity from her new diminutive pals. When animated, kids make better adventurers, plain and simple.

“Hoppers” continues Pixar’s run of humble, charming originals (“Luca,” “Elio”) in between billion-dollar-grossing, idea-starved sequels (“Inside Out 2,” probably “Toy Story 5”). The Disney-owned studio’s days of irrepressible innovation and unmatched imagination are well behind it. No one’s awed by anything anymore. “Coco,” almost 10 years ago, was their last new property to wow on the scale of peak Pixar.

Look, the new movie is likable and has a brain, heart and ample laughs. That’s more than I can say for most family fare. “A Minecraft Movie” made me wanna hop right out of the theater.

Entertainment

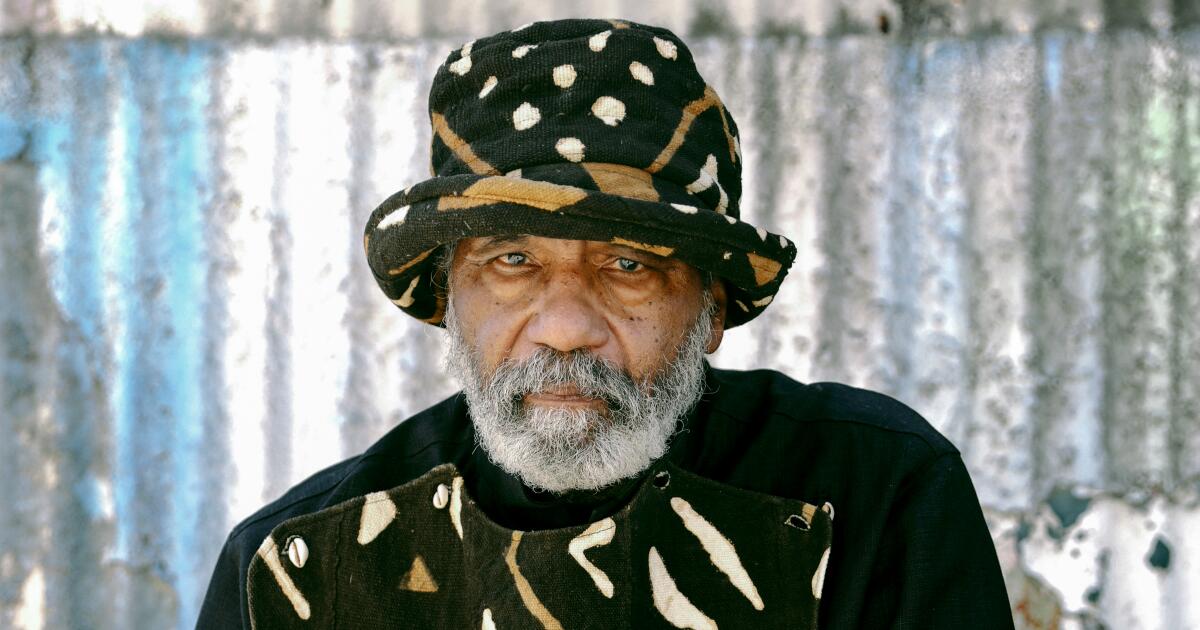

Ulysses Jenkins, Los Angeles artist and pioneer of Black experimental video, dies at 79

Ulysses Jenkins, the pioneering Los Angeles-born video artist whose avant-garde compositions embodied Black experimentalism, has died. He was 79.

Jenkins’ death was confirmed by his alma mater Otis College, where he studied under renowned painter and printmaker Charles White in the late 1970s and returned as an instructor years later. The Los Angeles art and design school shared a statement from the Charles White Archive, which said, “Jenkins had a profound impact on contemporary art and media practices.”

“A trailblazing figure in Black experimental video, he was widely recognized for works that used image, sound, and cultural iconography to examine representation, race, gender, ritual, history, and power,” the statement said.

A self-proclaimed “griot,” Jenkins throughout his decades-spanning career maintained an art practice grounded in the tradition of those West African oral historians who came before him. Through archival documentaries like “The Nomadics” and surrealist murals like “1848: Bandaide,” he leveraged alternative media to challenge Eurocentric representations of Black Americans in popular culture.

He was both an artist and a storyteller who sought to “reassert the history and the culture,” he told The Times in 2022. That year, the Hammer Museum presented Jenkins’ first major retrospective, “Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation.”

“Early video art was about the problems with the media that we are still having today: the notions of truth,” Jenkins said. “To that extent, early video art was a construct that was anti-media … a critical analysis of the media that we were viewing every night.”

Born in 1946 to Los Angeles transplants from the South, Jenkins was ambivalent about the city, which offered his parents some refuge from the blatant systemic racism they encountered in their hometowns, but housed an entertainment industry that had long perpetuated anti-Black sentiment.

“What Hollywood represents, especially in my work, is the classic plantation mentality,” Jenkins told The Times in 1986. “Although people aren’t necessarily enslaved by it, people enslave themselves to it because they’re told how fantastic it is to help manifest these illusions for a corporate sponsor.”

Jenkins, who participated in a group of artists committed to spontaneous action called Studio Z, was naturally drawn to video art over Hollywood filmmaking. “I can address any issue and I don’t have to wait for [the studios’] big OK. I thought this was a land of freedom, and video allows me that freedom and opportunity that I can create for myself and at least feel that part of being an American,” he said.

Jenkins went on to deconstruct Hollywood’s vision of the Black diaspora in experimental video compositions including “Mass of Images,” which incorporates clips from D.W. Griffith’s notoriously racist “The Birth of a Nation,” and “Two-Tone Transfer,” which depicts, in Jenkins’ words, a “dreamscape in which the dreamer awakens to a visitation of three minstrels who tell the story of the development of African American stereotypes in the American entertainment industry.”

Jenkins’ legacy is not only artistic but institutional, with the luminary having held teaching appointments at UCSD and UCI, where he co-founded the digital filmmaking minor with fellow Southern California-based artists Bruce Yonemoto and Bryan Jackson.

As artist and educator Suzanne Lacy penned in her social media tribute to Jenkins, which showed him speaking to students at REDCAT in L.A., “he has been an important part of our histories here in Southern California as video and performance artists evolved their practices.”

Movie Reviews

Review | Hoppers: Pixar’s new animation is a hilarious, heartfelt animal Avatar

4/5 stars

Bounding into cinemas just in time for spring, the latest Pixar animation is a pleasingly charming tale of man vs nature, with a bit of crazy robot tech thrown in.

The star of Hoppers is Mabel Tanaka (voiced by Piper Curda), a young animal-lover leading a one-girl protest over a freeway being built through the tranquil countryside near her hometown of Beaverton.

Because the freeway is the pet project of the town’s popular mayor, Jerry (Jon Hamm), who is vying for re-election, Mabel’s protests fall on deaf ears.

Everything changes when she stumbles upon top-secret research by her biology professor, Dr Sam Fairfax (Kathy Najimy), that allows for the human consciousness to be linked to robotic animals. This lets users get up close and personal with other species.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO6 days ago

Denver, CO6 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoArturia’s FX Collection 6 adds two new effects and a $99 intro version

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: How Lunar New Year Traditions Take Root Across America

-

Florida2 days ago

Florida2 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days