Entertainment

A Grammy-winning producer. An incarcerated father. And a 'fairy tale' reunion

Snoop Dogg’s private, self-branded Doggyland casino resides in an unmarked building in Inglewood, and on a mid-January on Monday, its paisley print blackjack table and Indoggo branded bar were commandeered by Buffalo, N.Y., rapper Benny the Butcher for a video shoot.

With cameras rolling, Snoop and Benny cackled in drunken laughter at the center of the scene, while rapping along to their forthcoming collaboration. To their left sat Hit-Boy, the song’s producer, while Big Hit — Hit-Boy’s father — served as a human money counter on their right, throwing bills and twisting fingers.

“Big Hit, what up?” Snoop Dogg exclaimed as the two exchanged a dap in between shots. “I just bought your album again. Too damn important.”

Later that same week — on the other side of a quick Las Vegas sprint that found them in an impromptu session with Ty Dolla Sign — Hit-Boy and Big Hit hunkered down at Chalice Studios, bobbing heads in unison while watching and rewatching the final product. Once they’ve soaked in every shot to their satisfaction, Hit-Boy plopped in front of his computer and scrolled through his assortment of samples; as soon as he settled on a vocal chop, Big Hit worked through a verse idea, freestyling references and metaphors while trying to catch the beat.

“All of this is a dream come true,” said Big Hit, 52. “It feels like a fairy tale.”

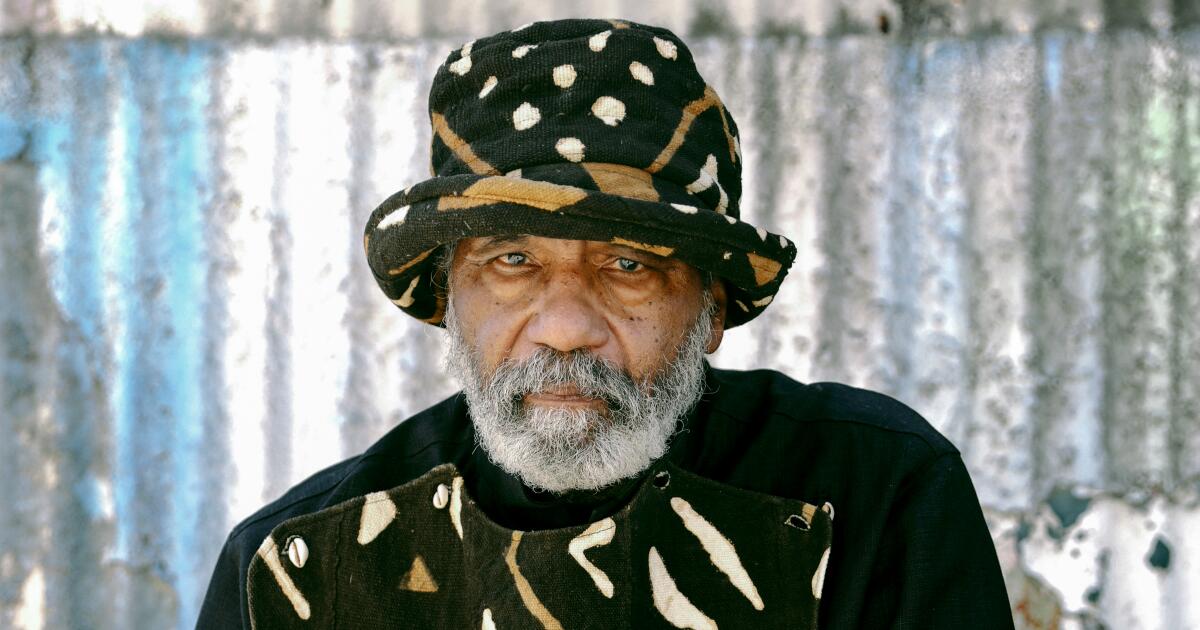

“I lost everything,” says Big Hit of his time in prison. “The struggle is real in there.”

(Walter W. Brady / For The Times)

This freewheeling schedule of studios, shoots and A-list shoulder-rubbing is now the norm for Big Hit, born Chauncey Hollis Sr., who’s fast-tracking the rap career he’s long envisioned in tandem with his son. But it’s also wholly unfamiliar. Big Hit has spent most of his adult life in prison on drug-related charges — from 1991 to 2004, with intermittent stints to follow — laying his head in a cell as Hit-Boy (Chauncey Hollis Jr.) established himself as one of hip-hop’s dominant producers.

While shuffling through the system, Big Hit says, he survived a brutal jumping at the hands of authorities that left him flatlined and strapped to a gurney as doctors questioned if he’d survive. “They had us standing from cell to cell for like a week, waiting to get a bed,” he recalled. “We made a plan to stand up for our rights, and got screamed on and boo-bopped. They went overboard with me, because I was the one who wouldn’t stop.”

In prison, he contracted COVID three separate times. Workouts required cramming letters into bags to facilitate bicep curls; he learned to stuff his bed sheets in the vents to catch the dust and protect from respiratory illness. When he was released in May 2023, he brought home his final prison meal — two slices of bread and bologna — as a spoiled reminder of the conditions he survived, and the place he can’t allow himself to return.

“I wish I had somebody to really tell me the other side of the dope game,” he said. “It was all true — the glitter, the girls, the cars, the money, and all that. But people wouldn’t lace you up on the darker side of the situation. I lost everything. The struggle is real in there.”

Meanwhile on the outside, Hit-Boy, 36, dove headfirst into music while stashing earnings to send to his father and care for his mother. His most commercially successful creations are as thunderous as they are unavoidable: Kanye West and Jay-Z’s “N— in Paris,” Kendrick Lamar’s “Backseat Freestyle,” Beyoncé’s “Sorry,” Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode.”

Hit-Boy attends the Grammy Awards in 2022.

(Johnny Nunez / Getty Images for The Recording Academy)

This February he’ll return to the Grammys, where he’s again nominated for producer of the year, and for the first time in his career, he’ll walk the red carpet with his mother, father and 3-year-old son.

It’s a moment he and his father have long visualized.

“I’ve won three Grammys, but my pops has never been out to see it,” Hit-Boy said. “We want that producer of the year award. Not too many Black people have even been nominated — let alone won — so being considered is already dope. It’d mean a lot to the younger me; ‘you really did what you wanted to do.’ ”

But beyond the gold trophy, Hit-Boy’s primary focus has been helping his father establish a new life, rehabilitated through the music rather than the streets. It’s a dream birthed in 2014, when Big Hit featured on Hit-Boy’s posse cut “Grindin’ My Whole Life” and caught a local hit through the waterworks-inducing “G’z Don’t Cry,” but the candle was snuffed out after Big Hit committed a hit-and-run in Humboldt County, sending him away once again, this time for nine years. (Big Hit says he was robbed after the crash and fled the scene as gunshots rang out, and didn’t know someone in the other car had been gravely injured.)

“He’s been out eight months,” says Hit-Boy, right, of his father, left, “but it’s really 30 years of programming. A lot of his life was taken from him.”

(Walter W. Brady / For The Times)

Rather than working side-by-side in the studio, Big Hit wrote rhymes in prison, plotting an eventual debut album that would be produced by his son. In December 2023, the vision was realized through “The Truth Is in My Eyes,” which wraps a lifetime’s worth of street tales into a triumphant body of work. On this album (and on “Paisley Dreams,” a collaboration project with the Game), Big Hit spits each word as if the mic could be snatched away from him at any moment.

The studio has become a safe haven for Big Hit as he acclimates himself to an entirely new world. It’s a task easier said than done, but those with a front row seat are already seeing the shift in his mind set.

“I sat with him in the studio for hours when he had been out for maybe 10 days, and the yard was still on him, in terms of his energy,” said DJ Hed, host at the Inglewood-based Home Grown Radio.

“He was ready to go back to what he knew how to do, to get some money,” DJ Hed continued. “I had to tell him, ‘Your son is really a legend out here, and if you go all in with the music, I think it’ll work out for you.’ I saw him at his release party, and he told me he was all for the music now, offers on the table, making money. It was a moment that reminded me why I do what I do.”

“It’s years and years of him being desensitized, thinking to himself that if he’s not seeing it right here right now, it’s not happening,” Hit-Boy said. “He’s been out eight months, but it’s really 30 years of programming. A lot of his life was taken from him.”

“What we’re doing is miraculous,” says Hit-Boy, right. “I’ve had people say, ‘Y’all made me reach out to my dad again.’ That’s priceless to me.”

(Walter W. Brady / For The Times)

Big Hit endured a rough upbringing in Pasadena. His father, who grew up an orphan, smoke and drank with him. Big Hit was an alcoholic before he reached his teens.

He calls himself a “young brat” who made a habit of cussing out his teachers and getting into fights.

“By the time [my father] saw I was out of control, it was too late,” he said. “That beast had been shaped and molded in me. I remember one day we were on the porch, and he said, ‘You want to be just like your daddy, huh.’ I looked him in the eyes, and he told me, ‘N—, you scaring me.’ He tried to change it, but it was too late.”

Big Hit ran away at the age of 11 and turned to the streets; a natural hustler, he advanced through the ranks quickly. In 1991, he was caught with 3 kilograms of cocaine, more than a dozen guns and bundles of cash.

Hit-Boy had just turned 5 years old when his father was convicted and sent to prison for what would become 13 years, and although the two did their best to stay in contact, he felt the pain of his dad’s absence. Hit-Boy and his mother moved around Los Angeles, sleeping on floors or at friends’ and relatives’ places; at one point, the family resided in Upland, where a 2-for-99-cents promotion at Arby’s became their daily sustenance.

Hit-Boy’s uncle, Rodney Benford, was a member of Troop, the Pasadena R&B group who scored a smattering of R&B hits in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Some of Hit-Boy’s earliest memories were nights at his uncle’s house, giving him a firsthand look at the life a successful music career could facilitate.

“I’d go to prison to see my dad, and then I’m going back to my uncle’s house, and he’s throwing a party,” he said. “I saw the worst of the worst in prison, and the best of the best with my uncle.”

Hit-Boy tried to follow in his uncle’s footsteps and create a rap group, until his collaborators pushed the founder out of the picture. He took his future into his own hands instead, learning how to produce with a cracked copy of FL Studio and rapping into a USB microphone.

Navigating the business has proved the toughest part of the journey; seeking quick cash, Hit-Boy signed a production deal with Universal Music Publishing Group in 2007, to which he remains tied after more than a decade of fighting.

“I realized it was a bad deal in 2011, when ‘N— in Paris’ came out,” Hit-Boy said. “I thought I had my hit, it was all over the radio, so I went to UMPG, saying I need a check. They were like, ‘You already signed this contract, so it’s nothing we can really do for you.’ ”

(Thanks to help from Jay-Z and Roc Nation Chief Executive Officer Desiree Perez, he was able to finally secure an end date to his UMPG contract that will soon allow him to move on.)

Recently, he’s hit a hot streak on his joint albums with Nas, the first of which (“King’s Disease,” 2021) earned the Queens legend his first Grammy. But other high-profile collaborations have been bittersweet — Hit-Boy and his manager said the producer is still chasing royalties from a number of multi-platinum records made with major label artists.

“You’ll help someone have one of their biggest moments, and they’ll act like they don’t even know you,” Hit-Boy said. “I’ve won Grammys with people I can’t get in contact with.”

Stories like that are one reason why Hit-Boy and his dad are attempting to chart a new path, betting on themselves and building it all in-house. Nothing about what they’re doing is conventional — a 52-year-old rapper, releasing his debut album executive produced by his son. For them, releasing “The Truth Is in My Eyes” exclusively for purchase on Bandcamp, rather than making it available for streaming on Spotify and other platforms, was another empowering move, allowing true supporters to connect with the music in a deeper way.

But even more important than the album’s sales is the impact it’s already made in the community.

“I was talking to the Game, and he was telling me how many people have tried to put their cousin, or their uncle, or their family on, and it did not work at all,” Hit-Boy said. “What we’re doing is miraculous. I’ve had people say, ‘Y’all made me reach out to my dad again.’ That’s priceless to me. That’s the success.”

Movie Reviews

‘Hoppers’ review: Who can argue with hilarious talking animals?

Just when you think Pixar’s petting-zoo cute new movie “Hoppers” is flagrantly ripping off James Cameron, the characters come clean.

movie review

HOPPERS

Running time: 105 minutes. Rated PG (action/peril, some scary images and mild language). In theaters March 6.

“You guys, this is like ‘Avatar’!,” squeals 19-year-old Mabel (Piper Curda), the studio’s rare college-age heroine.

Shoots back her nutty professor, Dr. Fairfax (Kathy Kajimy): “This is nothing like ‘Avatar!’”

Sorry, Doc, it definitely is. And that’s fine. Placing the smart sci-fi story atop an animated family film feels right for Pixar, which has long fused the technological, the fantastical and the natural into a warm signature blend. Also, come on, “Avatar” is “Dances With Wolves” via “E.T.”

What separates “Hoppers” from the pack of recent Pix flix, which have been wholesome as a church bake sale, is its comic irreverence.

Director Daniel Chong’s original movie is terribly funny, and often in an unfamiliar, warped way for the cerebral and mushy studio. For example, I’ve never witnessed so many speaking characters be killed off in a Pixar movie — and laughed heartily at their offings to boot.

What’s the parallel to Pandora? Mabel, a budding environmental activist, has stumbled on a secret laboratory where her kooky teachers can beam their minds into realistic robot animals in order to study them. They call the devices “hoppers.”

Bold and fiery Mabel — PETA, but palatable — sees an opportunity.

The mayor of Beaverton, Jerry (Jon Hamm), plans to destroy her beloved local pond that’s teeming with wildlife to build an expressway. And the only thing stopping the egomaniacal pol — a more upbeat version of President Business from “The Lego Movie” — is the water’s critters, who have all mysteriously disappeared.

So, Mabel avatars into beaver-bot, and sets off in search of the lost creatures to discover why they’ve left.

From there, the movie written by Jesse Andrews (“Luca”) toys with “Toy Story.” Here’s what mischief fuzzy mammals, birds, reptiles and insects get up to when humans aren’t snooping around. Dance aerobics, it turns out.

Per the usual, “Hoppers” goes deep inside their intricate society. The beasts have a formal political system of antagonistic “Game of Thrones”-like royal houses. The most menacing are the Insect Queen (Meryl Streep — I’d call her a chameleon, but she’s playing a bug), a staunch monarch butterfly and her conniving caterpillar kid (Dave Franco). They’re scheming for power.

Perfectly content with his station is Mabel’s new best furry friend King George (Bobby Moynihan), a gullible beaver who ascended to the throne unexpectedly. He happily enforces “pond rules,” such as, “When you gotta eat, eat.”

That means predators have free rein to nosh on prey, and everybody’s cool with it. Because of bone-dry deliveries, like exhausted office drones, the four-legged cast members are hilarious as they go about their Animal Planet activities.

No surprise — talking lizards, sharks, bears, geese and frogs are the real stars here. They far outshine Mabel, even when she dons beaver attire. Much like a 19-year-old in a job interview, she doesn’t leave much of an impression.

Yes, the teen has a heartfelt motivation: The embattled pond was her late grandma’s favorite place. Mabel promised her that she’d protect it.

But in personality she doesn’t rank as one of Pixar’s most engaging leads, perhaps because she’s past voting age. Mabel is nestled in a nebulous phase between teenage rebellion and adulthood that’s pretty blasé, even if a touch of tension comes from her hiding her Homo sapien identity from her new diminutive pals. When animated, kids make better adventurers, plain and simple.

“Hoppers” continues Pixar’s run of humble, charming originals (“Luca,” “Elio”) in between billion-dollar-grossing, idea-starved sequels (“Inside Out 2,” probably “Toy Story 5”). The Disney-owned studio’s days of irrepressible innovation and unmatched imagination are well behind it. No one’s awed by anything anymore. “Coco,” almost 10 years ago, was their last new property to wow on the scale of peak Pixar.

Look, the new movie is likable and has a brain, heart and ample laughs. That’s more than I can say for most family fare. “A Minecraft Movie” made me wanna hop right out of the theater.

Entertainment

Ulysses Jenkins, Los Angeles artist and pioneer of Black experimental video, dies at 79

Ulysses Jenkins, the pioneering Los Angeles-born video artist whose avant-garde compositions embodied Black experimentalism, has died. He was 79.

Jenkins’ death was confirmed by his alma mater Otis College, where he studied under renowned painter and printmaker Charles White in the late 1970s and returned as an instructor years later. The Los Angeles art and design school shared a statement from the Charles White Archive, which said, “Jenkins had a profound impact on contemporary art and media practices.”

“A trailblazing figure in Black experimental video, he was widely recognized for works that used image, sound, and cultural iconography to examine representation, race, gender, ritual, history, and power,” the statement said.

A self-proclaimed “griot,” Jenkins throughout his decades-spanning career maintained an art practice grounded in the tradition of those West African oral historians who came before him. Through archival documentaries like “The Nomadics” and surrealist murals like “1848: Bandaide,” he leveraged alternative media to challenge Eurocentric representations of Black Americans in popular culture.

He was both an artist and a storyteller who sought to “reassert the history and the culture,” he told The Times in 2022. That year, the Hammer Museum presented Jenkins’ first major retrospective, “Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation.”

“Early video art was about the problems with the media that we are still having today: the notions of truth,” Jenkins said. “To that extent, early video art was a construct that was anti-media … a critical analysis of the media that we were viewing every night.”

Born in 1946 to Los Angeles transplants from the South, Jenkins was ambivalent about the city, which offered his parents some refuge from the blatant systemic racism they encountered in their hometowns, but housed an entertainment industry that had long perpetuated anti-Black sentiment.

“What Hollywood represents, especially in my work, is the classic plantation mentality,” Jenkins told The Times in 1986. “Although people aren’t necessarily enslaved by it, people enslave themselves to it because they’re told how fantastic it is to help manifest these illusions for a corporate sponsor.”

Jenkins, who participated in a group of artists committed to spontaneous action called Studio Z, was naturally drawn to video art over Hollywood filmmaking. “I can address any issue and I don’t have to wait for [the studios’] big OK. I thought this was a land of freedom, and video allows me that freedom and opportunity that I can create for myself and at least feel that part of being an American,” he said.

Jenkins went on to deconstruct Hollywood’s vision of the Black diaspora in experimental video compositions including “Mass of Images,” which incorporates clips from D.W. Griffith’s notoriously racist “The Birth of a Nation,” and “Two-Tone Transfer,” which depicts, in Jenkins’ words, a “dreamscape in which the dreamer awakens to a visitation of three minstrels who tell the story of the development of African American stereotypes in the American entertainment industry.”

Jenkins’ legacy is not only artistic but institutional, with the luminary having held teaching appointments at UCSD and UCI, where he co-founded the digital filmmaking minor with fellow Southern California-based artists Bruce Yonemoto and Bryan Jackson.

As artist and educator Suzanne Lacy penned in her social media tribute to Jenkins, which showed him speaking to students at REDCAT in L.A., “he has been an important part of our histories here in Southern California as video and performance artists evolved their practices.”

Movie Reviews

Review | Hoppers: Pixar’s new animation is a hilarious, heartfelt animal Avatar

4/5 stars

Bounding into cinemas just in time for spring, the latest Pixar animation is a pleasingly charming tale of man vs nature, with a bit of crazy robot tech thrown in.

The star of Hoppers is Mabel Tanaka (voiced by Piper Curda), a young animal-lover leading a one-girl protest over a freeway being built through the tranquil countryside near her hometown of Beaverton.

Because the freeway is the pet project of the town’s popular mayor, Jerry (Jon Hamm), who is vying for re-election, Mabel’s protests fall on deaf ears.

Everything changes when she stumbles upon top-secret research by her biology professor, Dr Sam Fairfax (Kathy Najimy), that allows for the human consciousness to be linked to robotic animals. This lets users get up close and personal with other species.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO6 days ago

Denver, CO6 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoArturia’s FX Collection 6 adds two new effects and a $99 intro version

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: How Lunar New Year Traditions Take Root Across America