Business

Paramount was poised to buy Warner Bros. Discovery. What went wrong?

Oracle founder Larry Ellison was on the cusp of conquering Hollywood.

Just four months earlier, he had bankrolled his son David’s $8-billion acquisition of the storied Paramount Pictures.

Now the Ellison family had designs on scooping up Warner Bros. Discovery, too, offering to buy the entire company for at least $60 billion. The bold play had suddenly thrust this Silicon Valley titan and his son, David — chief executive of the newly-merged Paramount Skydance — into one of the most powerful positions in the film and TV industry.

By most outward appearances, Warner Bros. Discovery was theirs for the taking. Wall Street analysts, Hollywood insiders and even some of the other bidders expected Paramount to prevail. After all, it was backed by one of the world’s richest men. And it even had the blessing of President Trump, who openly expressed his preference for the Paramount bid.

But Ellison’s crowning moment was ruined when Netflix swooped in Friday announcing its own blockbuster deal.

The streamer snapped up Warner Bros. in a $82.7-billion deal for the Burbank-based film and television studios, HBO Max and HBO, delivering a massive blow to Ellison and his son, David.

In the Paramount bid, Larry Ellison was once again the primary backer. But the Warner Bros. Discovery board believed the Netflix offer of $27.75 a share, which did not include CNN or other basic cable channels, was a better deal for shareholders.

The announcement stunned many who had predicted that Paramount would prevail in the contentious auction. It also marked a rare defeat for Ellison, who was outmaneuvered by none other than Netflix’s co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos and his team.

Analysts and multiple auction insiders told The Times several factors complicated the process, including Paramount’s low-ball offers and hubris.

“This is a bad day for for Paramount and for the Ellisons,” said Lloyd Greif, president and chief executive of Greif & Co., a Los Angeles-based investment bank. “They were overconfident because they underestimated the competition.”

Representatives of Paramount and Warner declined to comment. A representative for Ellison at Oracle did not respond to requests for comment.

Characteristically, Ellison is not backing down, say sources close to the tech mogul who were not authorized to comment. Paramount — whose chief legal counsel is the former head of the U.S. Justice Department’s antitrust division during the first Trump term — is preparing for a legal battle with Warner Bros. over the handling of the auction. They are expected to urge the Securities & Exchange Commission and the Department of Justice to investigate claims that the Netflix deal would be anticompetitive and harmful to consumers and theater owners.

Paramount’s lawyers sent Warner Bros. Discovery Chief Executive David Zaslav a blistering letter Wednesday, accusing the studio of rigging the process in favor of a “single bidder” and “abdicating its duties to stockholders.”

What went wrong

Several sources said Paramount’s first mistake was making low-ball offers.

Paramount submitted three unsolicited bids by mid-October, the first for $19 a share. Warner’s board of directors unanimously rejected all of the bids as too low.

Top Warner Bros. executives were incensed, feeling that the Ellisons had just shown up in Hollywood and now were throwing their weight around to take advantage of Warner Bros.’ struggles.

Paramount had Larry Ellison guaranteeing its Warner bid with $30 billion of his Oracle stock, according to one knowledgeable person who was not authorized to comment.

But as the price of Warner went higher, Paramount needed considerably more money. It turned to private equity firm Apollo Global Management.

In late October, Warner opened the bidding to other suitors. Netflix and Comcast jumped in. Paramount’s leaders seemed to underestimate Netflix, according to several people close to the auction. A senior Netflix executive had publicly downplayed its interest.

“Maybe Netflix was playing possum,” said Paul Hardart, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

Paramount “thought they were the only game in town,” said a person close to the auction who was not authorized to comment.

At one point, Paramount’s team seemed more concerned about the movements of Comcast Chairman Brian Roberts, who had visited Saudi Arabia, reportedly on theme park business.

David Ellison and RedBird’s Gerry Cardinale were scrambling to line up Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds to provide more financing for their offer.

“They were going around trying to get money from elsewhere and that probably sowed some doubts among the board at Warner Bros. Discovery,” Hardart said.

Paramount’s negotiations with wealth funds for Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates were widely noted, people close to the auction said.

“It invited skepticism of the strength of the Paramount commitment,” said C. Kerry Fields, a business law professor at the USC Marshall School of Business.

When Oracle stock started dropping amid concerns of an AI bubble, it left Paramount‘s bid in a more precarious position.

Worries over Trump ties

In Hollywood, Larry Ellison’s close ties to Trump dampened enthusiasm for Paramount’s bid.

Oracle is among a group of U.S. investors expected to hold a majority stake in the U.S. business of TikTok, after the hugely popular video sharing app is spun out from Chinese parent company ByteDance — in no small part due to the influence and support from Trump.

This summer, Paramount agreed to pay $16 million to settle Trump’s lawsuit against CBS for its edits of a “60 Minutes” interview with Kamala Harris, as it was seeking to gain regulatory approval for the Ellison Skydance takeover. Days later, Paramount’s CBS announced that it was ending Stephen Colbert’s late-night talk show, citing its financial losses.

David Ellison in October made a controversial hire of the Free Press founder Bari Weiss to run CBS News — which delighted the president.

“Larry Ellison is great, and his son, David, is great,” Trump told reporters in mid-October. “They’re big supporters of mine.”

After Trump’s reported intervention, Paramount agreed in late November to distribute Brett Ratner’s “Rush Hour 4,” a project that had been shelved amid sexual assault allegations against the director highlighted in a Los Angeles Times report. Ratner has disputed all the allegations against him.

“They were in the pole position with the Trump administration, but then that [position] started to be not as appealing to people,” Hardart said.

Last month, there was a meeting at the White House to discuss Paramount’s bid and the threat of Netflix, sources said. That same week, David Ellison was among the guests at a White House dinner hosted by Trump for Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia.

A report in the Guardian also raised alarm bells among some foreign regulators, one knowledgeable person said. The newspaper reported, citing anonymous sources, that White House officials had informally discussed with Larry Ellison several female CNN anchors whom Trump disliked and wanted fired should Paramount succeed in buying Warner.

People close to Paramount contend that Zaslav and his mentor, John Malone, who serves as a Warner board member emeritus, were biased against Paramount and that Zaslav is angling to retain his mogul status.

Paramount ultimately submitted six offers to Warner, including a final $30 a share offer, but none were as strong as Netflix’s proposal, said two people involved with the auction.

Paramount executives knew last Monday that they had been bested, according to people close to the company. Two days later, they lobbed a missive at Warner: “WBD appears to have abandoned the semblance and reality of a fair transaction process,” Paramount’s lawyers wrote.

Netflix said Friday its deal won’t close for a year to 18 months, the anticipated time it will take to win regulatory approval. That’s far from guaranteed, however, given possible antitrust concerns over Netflix’s market dominance.

Now they’re girding for fight with Warner Bros. Discovery over its handling of the auction.

Until recently, Larry Ellison was perhaps best known in Hollywood circles for playing himself in an “Iron Man 2” cameo during which Tony Stark refers to him as the “Oracle of Oracle” — and as the father who quietly bankrolled the film business careers of his children, David and Megan.

Those who know Larry Ellison say he should not be counted out.

At 81, a determined and resolute Ellison has shown no signs of slowing down. Although he stepped down as Oracle’s CEO in 2014, he remains its executive chairman and chief technology officer — and continues to be deeply involved in the company and its growing tentacles.

Larry Ellison, third from right at the White House with President Donald Trump, SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, appears to announce Stargate, a new AI infrastructure investment.

(Andrew Harnik / Getty Images)

“He keeps reinventing the company. Right when you think that they can’t figure it out, they figure it out and they’re pretty resilient,” said Brent Thill, a tech analyst at Jefferies.

The son of a 19-year-old unwed mother, Ellison grew up in a modest walk-up apartment on Chicago’s South Side, where he was raised by her aunt and uncle.

As he told Fox Business, “I had all the disadvantages necessary for success.”

Larry Ellison at the Oracle OpenWorld 2018 conference in San Francisco.

(Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Smart and headstrong, Ellison attended the University of Chicago, but dropped out and drove to California in a used Thunderbird. He got a job as a bank computer programmer, the first of several computer jobs at various companies.

In the early 1970s, Ellison began working on early databases for a company called Ampex. As the story goes, it became the precursor to Oracle’s systems.

By 1977, Ellison co-founded Oracle with $1,200 and ideas deeply inspired by an IBM research paper. The start-up transformed how companies and organizations stored, managed and retrieved huge volumes of data. The software company quickly became an influential tech giant. Oracle’s first contract was with the CIA.

In 1986, Oracle went public and seven years later Ellison landed for the first time on Forbes billionaire’s list, with a net worth of $1.6 billion.

Even among the ego-driven billionaire eccentrics of Silicon Valley, Ellison stood out. “The Difference Between God and Larry Ellison” is the title of a 1997 biography — one of at least 10 tomes examining the life of Larry.

Unlike many of his tech titan peers, who preferred quiet pursuits and carefully crafted public personas, Ellison reveled in his flamboyant escapades and the attention it attracted.

Ellison has flown fighter jets for fun, won the America’s Cup, twice (in 2010 and 2013), collected super yachts, mansions and samurai swords.

As both Oracle’s and Ellison’s fortunes swelled, he earned a reputation for ruthlessness. For years, his archnemesis was Microsoft founder Bill Gates. During the rival’s antitrust trial in 2000, Ellison not only admitted to hiring private investigators to go through Microsoft’s garbage but he also defended his actions, calling the move his “civic duty.”

Mike Wilson, one of Ellison’s biographers, called him “the Charles Foster Kane of the technological age.”

At Oracle, Ellison pushed to expand into cloud computing, healthcare and, more recently, artificial intelligence, forging close partnerships with AI chipmaking behemoth Nvidia, Meta and xAI.

Hollywood, however, was the domain of Ellison’s children, David and Megan, whom he had with his third wife, Barbara Boothe. They divorced shortly after Megan was born.

Larry Ellison and his children, the producers Megan Ellison and David Ellison.

(Lester Cohen / WireImage)

The Ellison scions grew up with their mother on a horse farm in Woodside, in the San Francisco Bay Area, and spent time with their father during school breaks, sailing around the world on one of his super yachts.

Early on, the tech entrepreneur set up trusts for his children with large tranches of stock in Oracle and later NetSuite, an enterprise software company he helped finance, that went public in 2007. Over time, the trusts, in addition to their independent holdings, have made David and Megan phenomenally wealthy.

With Ellison’s deep pockets, both pursued filmmaking. Megan launched Annapurna, an indie production company behind such acclaimed movies as “Zero Dark Thirty” and “Her.” David, after a brief, unsuccessful stint as an actor and producer of the 2006 flop “Flyboys,” established Skydance Media, bankrolling a slew of massive box office and television hits such as “Top Gun: Maverick,” “Star Trek” and “Grace and Frankie,” later broadening into animation, sports and gaming.

“David made money, his sister made the art,” said Stephen Galloway, dean of Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts.

And Larry Ellison often stepped in.

In 2018, he shepherded a major reorganization of Annapurna after the company stumbled into hundreds of millions in losses amid several box office misfires.

It was Ellison who put up the bulk of his son’s $8-billion bid to buy Paramount, the iconic studio, as well as CBS, MTV and other properties — and he holds nearly 78% of the newly formed company’s stock, making him its largest shareholder.

The Ellison family announced plans to remake the fabled Paramount studio through major investments, leveraging technology and building on popular franchises including “Top Gun,” “Star Trek” and “Yellowstone.”

And they aren’t ready to walk away from Warner Bros.

If history has proven anything, Ellison is always up for a fight.

Times staff writer Queenie Wong contributed to this report.

Business

Commentary: How Trump helped foreign markets outperform U.S. stocks during his first year in office

Trump has crowed about the gains in the U.S. stock market during his term, but in 2025 investors saw more opportunity in the rest of the world.

If you’re a stock market investor you might be feeling pretty good about how your portfolio of U.S. equities fared in the first year of President Trump’s term.

All the major market indices seemed to be firing on all cylinders, with the Standard & Poor’s 500 index gaining 17.9% through the full year.

But if you’re the type of investor who looks for things to regret, pay no attention to the rest of the world’s stock markets. That’s because overseas markets did better than the U.S. market in 2025 — a lot better. The MSCI World ex-USA index — that is, all the stock markets except the U.S. — gained more than 32% last year, nearly double the percentage gains of U.S. markets.

That’s a major departure from recent trends. Since 2013, the MSCI US index had bested the non-U.S. index every year except 2017 and 2022, sometimes by a wide margin — in 2024, for instance, the U.S. index gained 24.6%, while non-U.S. markets gained only 4.7%.

The Trump trade is dead. Long live the anti-Trump trade.

— Katie Martin, Financial Times

Broken down into individual country markets (also by MSCI indices), in 2025 the U.S. ranked 21st out of 23 developed markets, with only New Zealand and Denmark doing worse. Leading the pack were Austria and Spain, with 86% gains, but superior records were turned in by Finland, Ireland and Hong Kong, with gains of 50% or more; and the Netherlands, Norway, Britain and Japan, with gains of 40% or more.

Investment analysts cite several factors to explain this trend. Judging by traditional metrics such as price/earnings multiples, the U.S. markets have been much more expensive than those in the rest of the world. Indeed, they’re historically expensive. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index traded in 2025 at about 23 times expected corporate earnings; the historical average is 18 times earnings.

Investment managers also have become nervous about the concentration of market gains within the U.S. technology sector, especially in companies associated with artificial intelligence R&D. Fears that AI is an investment bubble that could take down the S&P’s highest fliers have investors looking elsewhere for returns.

But one factor recurs in almost all the market analyses tracking relative performance by U.S. and non-U.S. markets: Donald Trump.

Investors started 2025 with optimism about Trump’s influence on trading opportunities, given his apparent commitment to deregulation and his braggadocio about America’s dominant position in the world and his determination to preserve, even increase it.

That hasn’t been the case for months.

”The Trump trade is dead. Long live the anti-Trump trade,” Katie Martin of the Financial Times wrote this week. “Wherever you look in financial markets, you see signs that global investors are going out of their way to avoid Donald Trump’s America.”

Two Trump policy initiatives are commonly cited by wary investment experts. One, of course, is Trump’s on-and-off tariffs, which have left investors with little ability to assess international trade flows. The Supreme Court’s invalidation of most Trump tariffs and the bellicosity of his response, which included the immediate imposition of new 10% tariffs across the board and the threat to increase them to 15%, have done nothing to settle investors’ nerves.

Then there’s Trump’s driving down the value of the dollar through his agitation for lower interest rates, among other policies. For overseas investors, a weaker dollar makes U.S. assets more expensive relative to the outside world.

It would be one thing if trade flows and the dollar’s value reflected economic conditions that investors could themselves parse in creating a picture of investment opportunities. That’s not the case just now. “The current uncertainty is entirely man-made (largely by one orange-hued man in particular) but could well continue at least until the US mid-term elections in November,” Sam Burns of Mill Street Research wrote on Dec. 29.

Trump hasn’t been shy about trumpeting U.S. stock market gains as emblems of his policy wisdom. “The stock market has set 53 all-time record highs since the election,” he said in his State of the Union address Tuesday. “Think of that, one year, boosting pensions, 401(k)s and retirement accounts for the millions and the millions of Americans.”

Trump asserted: “Since I took office, the typical 401(k) balance is up by at least $30,000. That’s a lot of money. … Because the stock market has done so well, setting all those records, your 401(k)s are way up.”

Trump’s figure doesn’t conform to findings by retirement professionals such as the 401(k) overseers at Bank of America. They reported that the average account balance grew by only about $13,000 in 2025. I asked the White House for the source of Trump’s claim, but haven’t heard back.

Interpreting stock market returns as snapshots of the economy is a mug’s game. Despite that, at her recent appearance before a House committee, Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi tried to deflect questions about her handling of the Jeffrey Epstein records by crowing about it.

“The Dow is over 50,000 right now, she declared. “Americans’ 401(k)s and retirement savings are booming. That’s what we should be talking about.”

I predicted that the administration would use the Dow industrial average’s break above 50,000 to assert that “the overall economy is firing on all cylinders, thanks to his policies.” The Dow reached that mark on Feb. 6. But Feb. 11, the day of Bondi’s testimony, was the last day the index closed above 50,000. On Thursday, it closed at 49,499.50, or about 1.4% below its Feb. 10 peak close of 50,188.14.

To use a metric suggested by economist Justin Wolfers of the University of Michigan, if you invested $48,488 in the Dow on the day Trump took office last year, when the Dow closed at 48,448 points, you would have had $50,000 on Feb. 6. That’s a gain of about 3.2%. But if you had invested the same amount in the global stock market not including the U.S. (based on the MSCI World ex-USA index), on that same day you would have had nearly $60,000. That’s a gain of nearly 24%.

Broader market indices tell essentially the same story. From Jan. 17, 2025, the last day before Trump’s inauguration, through Thursday’s close, the MSCI US stock index gained a cumulative 16.3%. But the world index minus the U.S. gained nearly 42%.

The gulf between U.S. and non-U.S. performance has continued into the current year. The S&P 500 has gained about 0.74% this year through Wednesday, while the MSCI World ex-USA index has gained about 8.9%. That’s “the best start for a calendar year for global stocks relative to the S&P 500 going back to at least 1996,” Morningstar reports.

It wouldn’t be unusual for the discrepancy between the U.S. and global markets to shrink or even reverse itself over the course of this year.

That’s what happened in 2017, when overseas markets as tracked by MSCI beat the U.S. by more than three percentage points, and 2022, when global markets lost money but U.S. markets underperformed the rest of the world by more than five percentage points.

Economic conditions change, and often the stock markets march to their own drummers. The one thing less likely to change is that Trump is set to remain president until Jan. 20, 2029. Make your investment bets accordingly.

Business

How the S&P 500 Stock Index Became So Skewed to Tech and A.I.

Nvidia, the chipmaker that became the world’s most valuable public company two years ago, was alone worth more than $4.75 trillion as of Thursday morning. Its value, or market capitalization, is more than double the combined worth of all the companies in the energy sector, including oil giants like Exxon Mobil and Chevron.

The chipmaker’s market cap has swelled so much recently, it is now 20 percent greater than the sum of all of the companies in the materials, utilities and real estate sectors combined.

What unifies these giant tech companies is artificial intelligence. Nvidia makes the hardware that powers it; Microsoft, Apple and others have been making big bets on products that people can use in their everyday lives.

But as worries grow over lavish spending on A.I., as well as the technology’s potential to disrupt large swaths of the economy, the outsize influence that these companies exert over markets has raised alarms. They can mask underlying risks in other parts of the index. And if a handful of these giants falter, it could mean widespread damage to investors’ portfolios and retirement funds in ways that could ripple more broadly across the economy.

The dynamic has drawn comparisons to past crises, notably the dot-com bubble. Tech companies also made up a large share of the stock index then — though not as much as today, and many were not nearly as profitable, if they made money at all.

How the current moment compares with past pre-crisis moments

To understand how abnormal and worrisome this moment might be, The New York Times analyzed data from S&P Dow Jones Indices that compiled the market values of the companies in the S&P 500 in December 1999 and August 2007. Each date was chosen roughly three months before a downturn to capture the weighted breakdown of the index before crises fully took hold and values fell.

The companies that make up the index have periodically cycled in and out, and the sectors were reclassified over the last two decades. But even after factoring in those changes, the picture that emerges is a market that is becoming increasingly one-sided.

In December 1999, the tech sector made up 26 percent of the total.

In August 2007, just before the Great Recession, it was only 14 percent.

Today, tech is worth a third of the market, as other vital sectors, such as energy and those that include manufacturing, have shrunk.

Since then, the huge growth of the internet, social media and other technologies propelled the economy.

Now, never has so much of the market been concentrated in so few companies. The top 10 make up almost 40 percent of the S&P 500.

How much of the S&P 500 is occupied by the top 10 companies

With greater concentration of wealth comes greater risk. When so much money has accumulated in just a handful of companies, stock trading can be more volatile and susceptible to large swings. One day after Nvidia posted a huge profit for its most recent quarter, its stock price paradoxically fell by 5.5 percent. So far in 2026, more than a fifth of the stocks in the S&P 500 have moved by 20 percent or more. Companies and industries that are seen as particularly prone to disruption by A.I. have been hard hit.

The volatility can be compounded as everyone reorients their businesses around A.I, or in response to it.

The artificial intelligence boom has touched every corner of the economy. As data centers proliferate to support massive computation, the utilities sector has seen huge growth, fueled by the energy demands of the grid. In 2025, companies like NextEra and Exelon saw their valuations surge.

The industrials sector, too, has undergone a notable shift. General Electric was its undisputed heavyweight in 1999 and 2007, but the recent explosion in data center construction has evened out growth in the sector. GE still leads today, but Caterpillar is a very close second. Caterpillar, which is often associated with construction, has seen a spike in sales of its turbines and power-generation equipment, which are used in data centers.

One large difference between the big tech companies now and their counterparts during the dot-com boom is that many now earn money. A lot of the well-known names in the late 1990s, including Pets.com, had soaring valuations and little revenue, which meant that when the bubble popped, many companies quickly collapsed.

Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet and others generate hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue each year.

And many of the biggest players in artificial intelligence these days are private companies. OpenAI, Anthropic and SpaceX are expected to go public later this year, which could further tilt the market dynamic toward tech and A.I.

Methodology

Sector values reflect the GICS code classification system of companies in the S&P 500. As changes to the GICS system took place from 1999 to now, The New York Times reclassified all companies in the index in 1999 and 2007 with current sector values. All monetary figures from 1999 and 2007 have been adjusted for inflation.

Business

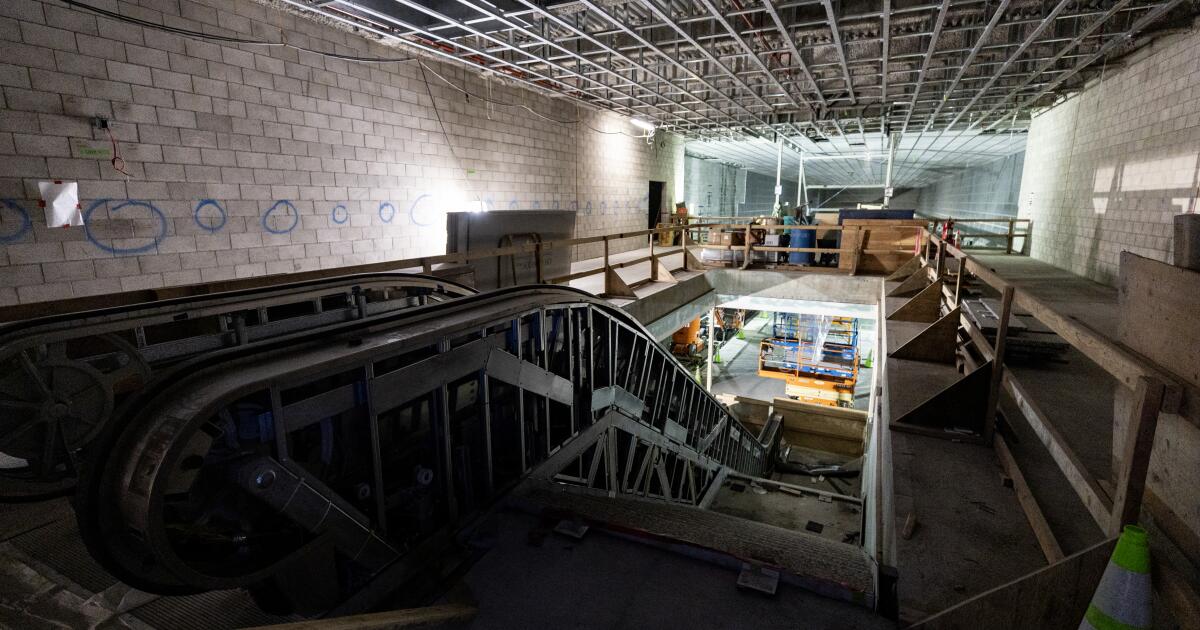

Coming soon: L.A. Metro stops that connect downtown to Beverly Hills, Miracle Mile

Metro has announced it will open three new stations connecting downtown Los Angeles to Beverly Hills in May.

The new stations mark the first phase of a rail extension project on the Metro D line, also known as the Purple Line, beneath Wilshire Boulevard. The extension will open to the public on May 8.

It’s part of a broader plan to enhance the region’s transit infrastructure in time for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The new stations will take riders west, past the existing Wilshire/Western station in Koreatown, and stopping along the Miracle Mile before arriving at Beverly Hills. The 3.92-mile addition winds through Hancock Park, Windsor Square, the Fairfax District and Carthay Circle. The stations will be located at Wilshire/La Brea, Wilshire/Fairfax and Wilshire/La Cienega.

This is the first of three phases in the D Line extension project. The completion of the this phase, budgeted at $3.7 billion, comes months later than earlier projections. Metro said in 2025 it expected to wrap up the phase by the end of the year.

The route between downtown Los Angeles and Koreatown is one of Metro’s most heavily used rail lines, with an average of around 65,000 daily boardings. The Purple Line extension project — with the goal of adding seven stations and expanding service on the line to Hancock Park, Century City, Beverly Hills and Westwood — broke ground more than a decade ago. Metro’s goal is to finish by the 2028 Summer Olympics.

In a news release on Thursday, Metro described its D Line expansion as “one of the highest-priority” transit projects in its portfolio and “a historic milestone.”

“Traveling through Mid-Wilshire to experience the culture, cuisine and commerce across diverse neighborhoods will be easier, faster and more accessible,” said Fernando Dutra, Metro board chair and Whittier City Council member, in the release. “That connectivity from Downtown LA to the westside will serve as a lasting legacy for all Angelenos.”

The D line was closed for more than two months last year for construction under Wilshire Boulevard, contributing to a 13.5% drop in ridership that was exacerbated by immigration raids in the area.

“I can’t wait for everyone to enjoy and discover the vibrance of mid-Wilshire without the traffic,” Metro CEO Stephanie Wiggins said in a statement.

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana4 days ago

Louisiana4 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making