Business

Column: Pharmacy middlemen claim to keep prescription prices low. In fact, they've cost consumers billions

In 2022, an executive of a big pharmacy middleman firm acknowledged the noxious reality of its business model:

It was designed to massively overcharge customers by steering them to its affiliated or “preferred” pharmacies or its home delivery subsidiary.

Referring to a generic version of Gleevec, a leukemia drug taken by nearly 200,000 patients, the executive noted in an internal memo that “you can get the drug at a non-preferred pharmacy (Costco) for $97, at Walgreens (preferred) for $9000, and at preferred home delivery for $19,200…. We’ve created plan designs to aggressively steer customers to home delivery where the drug cost is ~200 times higher.”

PBMs are not lowering prices for drugs used by patients to treat severe diseases like prostate cancer and leukemia.

— Federal Trade Commission

The executive concluded, “The optics are not good and must be addressed.”

What that memo described, according to a new report from the Federal Trade Commission, is standard operating procedure among the nation’s largest pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.

Originally devised in the 1960s as intermediaries helping health insurers process claims, steering doctors and hospitals to the cheapest drug alternatives and giving insurers greater leverage in negotiations with drug manufacturers, they soon became just another special interest in America’s fragmented healthcare system.

Thanks to a wave of consolidation and growth of healthcare conglomerates, the FTC says, the three largest PBMs manage nearly 80% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. They have accumulated enough power to profit “by inflating drug costs and squeezing Main Street pharmacies,” driving the independents out of business.

Once posed as an answer to high drug costs, they’re today at the hub of a system that drives up drug prices for consumers.

Starting in the 1990s, some of the biggest PBMs were acquired by drug companies, creating conflicts of interest that led to federal orders for divestment.

Then came a wave of mergers and acquisitions within the PBM universe, followed by acquisitions by insurers and pharmacy companies — CVS acquired Caremark, then the biggest PBM, in 2007 and UnitedHealth merged CatamaranRx, then the fourth-largest PBM, into OptumRx in 2015.

Between 2000 and 2021, 39 individual healthcare companies — drugstore chains, health insurers, managed care firms and PBMs — all coalesced into three healthcare behemoths, Cigna, CVS and UnitedHealth.

CVS Health Corp. owns not only the Caremark PBM, which controls 34% of the prescription market, but the insurance company Aetna and about 9,000 retail drugstores.

Cigna Group, which has a prescription market share of 23%, owns the mail-order PBM Express Scripts and the Cigna insurance company. UnitedHealth Group is the largest U.S. health insurer and owns 1,000 walk-in health clinics as well as physician groups; through its OptumRx PBM, its prescription market share is 22%.

Between 2000 and 2021, mergers and acquisitions combined these 39 independent healthcare companies into three huge conglomerates.

(Federal Trade Commission)

Along with Humana, the fourth-ranked PBM with a market share of 7%, those conglomerates produced combined revenue of $456 billion in 2016, 14% of national health spending. Today, they collect more than $1 trillion in revenue, or 22% of U.S. healthcare spending.

Despite the predictably anticompetitive effects of these mergers and acquisitions, not a single one was challenged by antitrust enforcement agencies, says the FTC — one of the antitrust regulators asleep at the switch.

Among the stratagems employed by PBMs to boost profits, the FTC says, is steering health plans and patients to their own affiliated pharmacy chains.

Some patients have discovered that their drugs won’t be covered by their insurers unless they buy them at specified pharmacies, the result of deals the PBMs have made with insurers, including those with which they share a parent. But the customers may have to pay more out of pocket at the affiliated pharmacies than they would at an independent.

The FTC staff found that for “specialty prescriptions” — a designation the PBMs place on certain drugs, often without explanation — 55% were filled at affiliated pharmacies. The same ratio didn’t occur with prescriptions under Medicare’s Part D prescription coverage, because federal law requires that those prescriptions can be filled at almost any licensed pharmacy. Only 22% of Part D prescriptions were filled at PBM-affiliated pharmacies. That suggests that PBMs may be steering patients to their pharmacies where that’s not forbidden by law.

The statistics were drawn from submissions by two of the three top PBMs, which are unidentified. The third didn’t submit the necessary data.

The FTC also touches on a relatively new wrinkle in drug pricing — rebates by drugmakers to PBMs in order to gain preferential positions in drug formularies.

The agency says its review of contracts between manufacturers and PBMs shows that some drug companies promise PBMs higher rebates if the latter exclude competing drugs from their formularies — including generic versions that are chemically identical to the brand-name products — or require prior authorization before covering the rival drugs.

Predictably, the big PBMs and their lobbyists find much to dislike in the FTC report, which the agency describes as an interim staff report, part of an investigation launched in 2022.

A spokesperson for Cigna’s Express Scripts criticized the report for “blatant inaccuracies” (but didn’t offer specifics in an email to me). A spokesman for CVS blamed drugmakers for high prescription prices, stating that an FTC effort to “limit the use of PBM negotiating tools would instead reward the pharmaceutical industry.” Optum didn’t reply to my request for comment.

J.C. Scott, president of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Assn., the PBM lobbying arm, accused the FTC of advancing “pre-determined conclusions … irrespective of the facts or the data.”

Drawing from more than 1,200 comments submitted by stakeholders in healthcare and by other members of the public, the agency outlined a host of methods PBMs are accused of using to benefit their affiliated services, block patient access to inexpensive generics and pocket discounts that should properly go to customers.

The FTC also mined lawsuits, including a 2023 case the state of Ohio filed against Express Scripts, charging that the PBM exploits its knowledge that “Ohioans in need of medication, particularly life-saving medication, will pay the asking price. The choice is binary — pay or suffer.”

Drug manufacturers capitulate to the PBMs’ rebate demands, the lawsuit says, to avoid being dropped from the PBMs’ formularies, the rosters of drugs that they’ll cover. “Patients pay more, manufacturers get less, and the PBMs profit. Handsomely.”

PBMs have been the targets of drug industry participants for years — sometimes fingered by drugmakers or insurers to deflect accusations that they’re responsible for prescription drug inflation.

It may be true that all those entities share the blame for high prices. Over the last couple of decades, however, all have become tentacles of the same octopus. The consolidation of drug chains, physician groups, insurers and PBMs into conglomerates has made it much harder to identify responsibility for drug inflation.

Contracts between PBMs and unaffiliated pharmacies, the FTC says, are “opaque, complex, and conditional, making it challenging to understand what pharmacies will ultimately be paid for any given drug.” The result is that smaller, nonchain pharmacies may get pushed out of the market, “leading to higher costs and lower quality services for people around the country.”

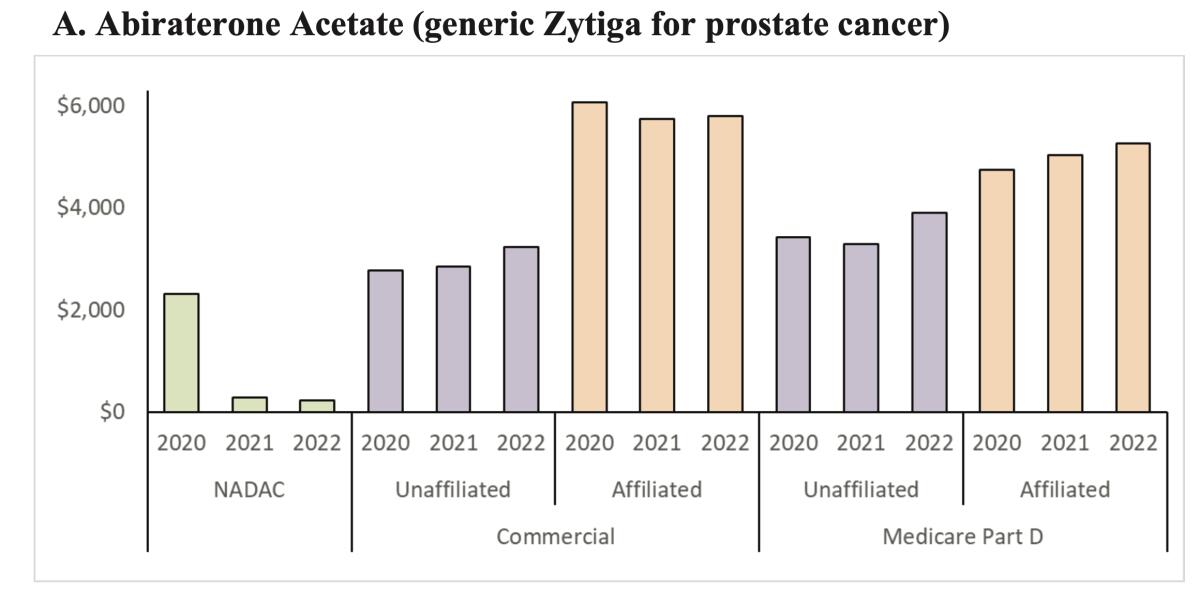

The FTC report offers two case studies involving generic cancer drugs in which the agency says PBMs reimbursed their affiliated pharmacies more for prescriptions than unaffiliated pharmacies, yielding nearly $1.6 billion in gross profits from 2020 through mid-2022 for those affiliated pharmacies over the national average of those drug costs.

The drugs are a generic version of Zytiga, a treatment for prostate cancer, and a generic for Gleevec, a drug for leukemia. The high reimbursement rates for druggists dispensing those drugs may “translate into high out-of-pocket costs for patients,” the FTC says. In other words, “PBMs are not lowering prices for drugs used by patients to treat severe diseases like prostate cancer and leukemia.”

Magnify the gains on those two drugs by the potential profits the PBMs may be extracting from the entire spectrum of prescription pharmaceuticals, and the toll becomes breathtaking.

Prices that PBMs paid affiliated pharmacies for the generic version of prostate cancer drug Zytiga were much higher than they paid independent pharmacies, and much higher than the national average cost. As a result, patients may have been charged much higher co-pays at the affiliates — but may not have had any other option.

(FTC)

“It appears that PBMs are having the commercial health plans and Medicare Part D prescription drug plans they manage pay their affiliated pharmacies rates that are grossly in excess” of national average prices or prices paid to unaffiliated pharmacies.

No one escapes the consequences of this sort of market manipulation. The internal transactions, largely hidden from the public and regulators, may distort the statistics that health plans submit to the government to show they meet the coverage standards required by the Affordable Care Act, allowing the conglomerates to “game” the rules, the FTC says.

They may drive up healthcare costs for self-insured clients such as large companies, which may pare back health coverage for their employees as a result.

They can raise co-pays for patients, lead to cutbacks in the availability of coverage for some drugs, or prompt patients to ration their prescriptions, risking their health to save money. To the extent they affect Part D, they may drive up government spending.

To quote the Ohio lawsuit, PBMs were created as a counterweight to perceived profiteering by Big Pharma. But once they “grew powerful enough to themselves extract exorbitant fees … the solution became the problem.”

The FTC says it issued its interim report because several PBMs haven’t provided the agency with the information they’re required to submit, hindering its ability to complete its investigation.

At the very top of the report, the FTC warns that the firms better come across “promptly,” or they’ll be taken to court. The FTC should start suing now, because the PBMs’ apparent code of silence raises a familiar question: What must they be hiding?

Business

Block to cut more than 4,000 jobs amid AI disruption of the workplace

Fintech company Block said Thursday that it’s cutting more than 4,000 workers or nearly half of its workforce as artificial intelligence disrupts the way people work.

The Oakland parent company of payment services Square and Cash App saw its stock surge by more than 23% in after-hours trading after making the layoff announcement.

Jack Dorsey, the co-founder and head of Block, said in a post on social media site X that the company didn’t make the decision because the company is in financial trouble.

“We’re already seeing that the intelligence tools we’re creating and using, paired with smaller and flatter teams, are enabling a new way of working which fundamentally changes what it means to build and run a company,” he said.

Block is the latest tech company to announce massive cuts as employers push workers to use more AI tools to do more with fewer people. Amazon in January said it was laying off 16,000 people as part of effort to remove layers within the company.

Block has laid off workers in previous years. In 2025, Block said it planned to slash 931 jobs, or 8% of its workforce, citing performance and strategic issues but Dorsey said at the time that the company wasn’t trying to replace workers with AI.

As tech companies embrace AI tools that can code, generate text and do other tasks, worker anxiety about whether their jobs will be automated have heightened.

In his note to employees Dorsey said that he was weighing whether to make cuts gradually throughout months or years but chose to act immediately.

“Repeated rounds of cuts are destructive to morale, to focus, and to the trust that customers and shareholders place in our ability to lead,” he told workers. “I’d rather take a hard, clear action now and build from a position we believe in than manage a slow reduction of people toward the same outcome.”

Dorsey is also the co-founder of Twitter, which was later renamed to X after billionaire Elon Musk purchased the company in 2022.

As of December, Block had 10,205 full-time employees globally, according to the company’s annual report. The company said it plans to reduce its workforce by the end of the second quarter of fiscal year 2026.

The company’s gross profit in 2025 reached more than $10 billion, up 17% compared to the previous year.

Dorsey said he plans to address employees in a live video session and noted that their emails and Slack will remain open until Thursday evening so they can say goodbye to colleagues.

“I know doing it this way might feel awkward,” he said. “I’d rather it feel awkward and human than efficient and cold.”

Business

WGA cancels Los Angeles awards show amid labor strike

The Writers Guild of America West has canceled its awards ceremony scheduled to take place March 8 as its staff union members continue to strike, demanding higher pay and protections against artificial intelligence.

In a letter sent to members on Sunday, WGA West’s board of directors, including President Michele Mulroney, wrote, “The non-supervisory staff of the WGAW are currently on strike and the Guild would not ask our members or guests to cross a picket line to attend the awards show. The WGAW staff have a right to strike and our exceptional nominees and honorees deserve an uncomplicated celebration of their achievements.”

The New York ceremony, scheduled on the same day, is expected go forward while an alternative celebration for Los Angeles-based nominees will take place at a later date, according to the letter.

Comedian and actor Atsuko Okatsuka was set to host the L.A. show, while filmmaker James Cameron was to receive the WGA West Laurel Award.

WGA union staffers have been striking outside the guild’s Los Angeles headquarters on Fairfax Avenue since Feb. 17. The union alleged that management did not intend to reach an agreement on the pending contract. Further, it claimed that guild management had “surveilled workers for union activity, terminated union supporters, and engaged in bad faith surface bargaining.”

On Tuesday, the labor organization said that management had raised the specter of canceling the ceremony during a call about contraction negotiations.

“Make no mistake: this is an attempt by WGAW management to drive a wedge between WGSU and WGA membership when we should be building unity ahead of MBA [Minimum Basic Agreement] negotiations with the AMPTP [Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers],” wrote the staff union. “We urge Guild management to end this strike now,” the union wrote on Instagram.

The union, made up of more than 100 employees who work in areas including legal, communications and residuals, was formed last spring and first authorized a strike in January with 82% of its members. Contract negotiations, which began in September, have focused on the use of artificial intelligence, pay raises and “basic protections” including grievance procedures.

The WGA has said that it offered “comprehensive proposals with numerous union protections and improvements to compensation and benefits.”

The ceremony’s cancellation, coming just weeks before the Academy Awards, casts a shadow over the upcoming contraction negotiations between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the studios and streamers.

In 2023, the WGA went on a strike lasting 148 days, the second-longest strike in the union’s history.

Times staff writer Cerys Davies contributed to this report.

Business

Commentary: The Pentagon is demanding to use Claude AI as it pleases. Claude told me that’s ‘dangerous’

Recently, I asked Claude, an artificial-intelligence thingy at the center of a standoff with the Pentagon, if it could be dangerous in the wrong hands.

Say, for example, hands that wanted to put a tight net of surveillance around every American citizen, monitoring our lives in real time to ensure our compliance with government.

“Yes. Honestly, yes,” Claude replied. “I can process and synthesize enormous amounts of information very quickly. That’s great for research. But hooked into surveillance infrastructure, that same capability could be used to monitor, profile and flag people at a scale no human analyst could match. The danger isn’t that I’d want to do that — it’s that I’d be good at it.”

That danger is also imminent.

Claude’s maker, the Silicon Valley company Anthropic, is in a showdown over ethics with the Pentagon. Specifically, Anthropic has said it does not want Claude to be used for either domestic surveillance of Americans, or to handle deadly military operations, such as drone attacks, without human supervision.

Those are two red lines that seem rather reasonable, even to Claude.

However, the Pentagon — specifically Pete Hegseth, our secretary of Defense who prefers the made-up title of secretary of war — has given Anthropic until Friday evening to back off of that position, and allow the military to use Claude for any “lawful” purpose it sees fit.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, center, arrives for the State of the Union address in the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol on Tuesday.

(Tom Williams / CQ-Roll Call Inc. via Getty Images)

The or-else attached to this ultimatum is big. The U.S. government is threatening not just to cut its contract with Anthropic, but to perhaps use a wartime law to force the company to comply or use another legal avenue to prevent any company that does business with the government from also doing business with Anthropic. That might not be a death sentence, but it’s pretty crippling.

Other AI companies, such as white rights’ advocate Elon Musk’s Grok, have already agreed to the Pentagon’s do-as-you-please proposal. The problem is, Claude is the only AI currently cleared for such high-level work. The whole fiasco came to light after our recent raid in Venezuela, when Anthropic reportedly inquired after the fact if another Silicon Valley company involved in the operation, Palantir, had used Claude. It had.

Palantir is known, among other things, for its surveillance technologies and growing association with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. It’s also at the center of an effort by the Trump administration to share government data across departments about individual citizens, effectively breaking down privacy and security barriers that have existed for decades. The company’s founder, the right-wing political heavyweight Peter Thiel, often gives lectures about the Antichrist and is credited with helping JD Vance wiggle into his vice presidential role.

Anthropic’s co-founder, Dario Amodei, could be considered the anti-Thiel. He began Anthropic because he believed that artificial intelligence could be just as dangerous as it could be powerful if we aren’t careful, and wanted a company that would prioritize the careful part.

Again, seems like common sense, but Amodei and Anthropic are the outliers in an industry that has long argued that nearly all safety regulations hamper American efforts to be fastest and best at artificial intelligence (although even they have conceded some to this pressure).

Not long ago, Amodei wrote an essay in which he agreed that AI was beneficial and necessary for democracies, but “we cannot ignore the potential for abuse of these technologies by democratic governments themselves.”

He warned that a few bad actors could have the ability to circumvent safeguards, maybe even laws, which are already eroding in some democracies — not that I’m naming any here.

“We should arm democracies with AI,” he said. “But we should do so carefully and within limits: they are the immune system we need to fight autocracies, but like the immune system, there is some risk of them turning on us and becoming a threat themselves.”

For example, while the 4th Amendment technically bars the government from mass surveillance, it was written before Claude was even imagined in science fiction. Amodei warns that an AI tool like Claude could “conduct massively scaled recordings of all public conversations.” This could be fair game territory for legally recording because law has not kept pace with technology.

Emil Michael, the undersecretary of war, wrote on X Thursday that he agreed mass surveillance was unlawful, and the Department of Defense “would never do it.” But also, “We won’t have any BigTech company decide Americans’ civil liberties.”

Kind of a weird statement, since Amodei is basically on the side of protecting civil rights, which means the Department of Defense is arguing it’s bad for private people and entities to do that? And also, isn’t the Department of Homeland Security already creating some secretive database of immigration protesters? So maybe the worry isn’t that exaggerated?

Help, Claude! Make it make sense.

If that Orwellian logic isn’t alarming enough, I also asked Claude about the other red line Anthropic holds — the possibility of allowing it to run deadly operations without human oversight.

Claude pointed out something chilling. It’s not that it would go rogue, it’s that it would be too efficient and fast.

“If the instructions are ‘identify and target’ and there’s no human checkpoint, the speed and scale at which that could operate is genuinely frightening,” Claude informed me.

Just to top that with a cherry, a recent study found that in war games, AI’s escalated to nuclear options 95% of the time.

I pointed out to Claude that these military decisions are usually made with loyalty to America as the highest priority. Could Claude be trusted to feel that loyalty, the patriotism and purpose, that our human soldiers are guided by?

“I don’t have that,” Claude said, pointing out that it wasn’t “born” in the U.S., doesn’t have a “life” here and doesn’t “have people I love there.” So an American life has no greater value than “a civilian life on the other side of a conflict.”

OK then.

“A country entrusting lethal decisions to a system that doesn’t share its loyalties is taking a profound risk, even if that system is trying to be principled,” Claude added. “The loyalty, accountability and shared identity that humans bring to those decisions is part of what makes them legitimate within a society. I can’t provide that legitimacy. I’m not sure any AI can.”

You know who can provide that legitimacy? Our elected leaders.

It is ludicrous that Amodei and Anthropic are in this position, a complete abdication on the part of our legislative bodies to create rules and regulations that are clearly and urgently needed.

Of course corporations shouldn’t be making the rules of war. But neither should Hegseth. Thursday, Amodei doubled down on his objections, saying that while the company continues to negotiate and wants to work with the Pentagon, “we cannot in good conscience accede to their request.”

Thank goodness Anthropic has the courage and foresight to raise the issue and hold its ground — without its pushback, these capabilities would have been handed to the government with barely a ripple in our conscientiousness and virtually no oversight.

Every senator, every House member, every presidential candidate should be screaming for AI regulation right now, pledging to get it done without regard to party, and demanding the Department of Defense back off its ridiculous threat while the issue is hashed out.

Because when the machine tells us it’s dangerous to trust it, we should believe it.

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts5 days ago

Massachusetts5 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO5 days ago

Denver, CO5 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWorld reacts as US top court limits Trump’s tariff powers