West

California Democrats urge feds to approve high-speed rail funding before DOGE nixes ‘boondoggle’

Several prominent California Democrats are calling on the U.S. Department of Transportation to approve a grant application for $536 million in federal funds to move forward with the state’s long-awaited high-speed rail network.

The monies would come from funds already allocated in general to “federal-state partnership[s] for intercity passenger rail grants” through the 2021 “Bipartisan Infrastructure Law” and made available via the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2024.

Democrats urged Secretary Pete Buttigieg to approve the funds, saying progress on the “California Phase I Corridor” is “essential to enhancing our nation’s and California’s strategic transportation network investments.”

“The Phase 1 Corridor aims to address climate concerns, promote health, improve access and connectivity, and boost economic vitality, while addressing current highway and rail capacity constraints,” a letter to the outgoing Cabinet member read.

BUILDING STARTS ON HIGH-SPEED RAIL LINE BETWEEN LAS VEGAS AND LOS ANGELES AREA

Drafted by Sen.-elect Adam Schiff, Sen. Alex Padilla, and California Democratic Reps. Jim Costa, Zoe Lofgren and Pete Aguilar, the letter calls for the funds to go to two projects in particular: tunneling through the Tehachapi Mountains in Southern California and through the Pacheco Pass of the Diablo Mountains in Northern California.

“These investments will continue to support living wage jobs, provide small business opportunities, and equitably enhance the mobility of communities in need – including disadvantaged agricultural communities – all while reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” Schiff and the other lawmakers wrote.

“Please consider the enormous value and meaningful impact that FSP-National grant funding will provide to advancing CAHSR beyond the Central Valley,” they told Buttigieg.

The bores are needed, the lawmakers said, to connect with other intercity passenger rail systems including the Brightline West, CalTrain, Metrolink and Altamont Commuter Express.

FLASHBACK: COMER TOUTS HUNTER BIDEN HEARING: RASKIN, SCHIFF ‘PULL STUFF OUT OF THEIR REAR’

Ongoing construction of the California bullet train project is photographed in Corcoran, California, left, and Hanford, California, right. (Getty)

According to California Republicans, the overall high-speed rail project is nearly $100 billion over budget and decades behind schedule.

Trump’s DOGE duo of Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy aren’t keen on the idea of continuing to fund what many Republicans consider a costly and unfruitful endeavor.

Rep. Kevin Kiley, R-Calif., said as much earlier this month in remarks on the House floor.

“I am very happy to report that the newly formed Department of Government Efficiency has honed-in on perhaps the single greatest example of government waste in United States history – and that is California’s high-speed-rail boondoggle,” Kiley said.

The official DOGE X account also described both California’s high-speed rail expenditures and requested funding in a November tweet.

Earlier this month, Ramaswamy also called the plans a “wasteful vanity project” that burned “billions in taxpayer cash with little prospect of completion in the next decade.”

He said Trump “correctly” rescinded $1 billion in federal funding for the project in 2019 and lamented President Biden’s reversal of that move.

“Time to end the waste,” Ramaswamy said.

California’s top state Senate Republican echoed the DOGE leaders’ concerns.

Sen. Alex Padilla (Getty Images)

“California’s ‘train to nowhere’ has already wasted billions of taxpayer dollars – now Biden wants all Americans to fund this boondoggle,” State Sen. Brian W. Jones of San Diego told Fox News Digital.

“When President Trump returns to office in a few weeks, he must defund the high-speed rail. This wasteful government experiment must end once and for all,” he added.

If approved, the federal funds will be bolstered by $134 million in state monies from California’s “cap & trade” program, according to the Sacramento Bee.

At a 2013 conference, Musk floated the idea of a “hyperloop” which was also presented in a white paper. Though it has not yet come to fruition, Musk said at the time he had thought whether there is a better way to get from Los Angeles to San Francisco than what California has proposed.

“The high-speed rail that’s being proposed would actually be the slowest bullet train in the world and the most expensive per-mile,” he said. “Isn’t there something better that we can come up with?”

The world’s richest man described Hyperloop at the time as a combination of a Concorde, a rail gun and an air-hockey table.

Read the full article from Here

West

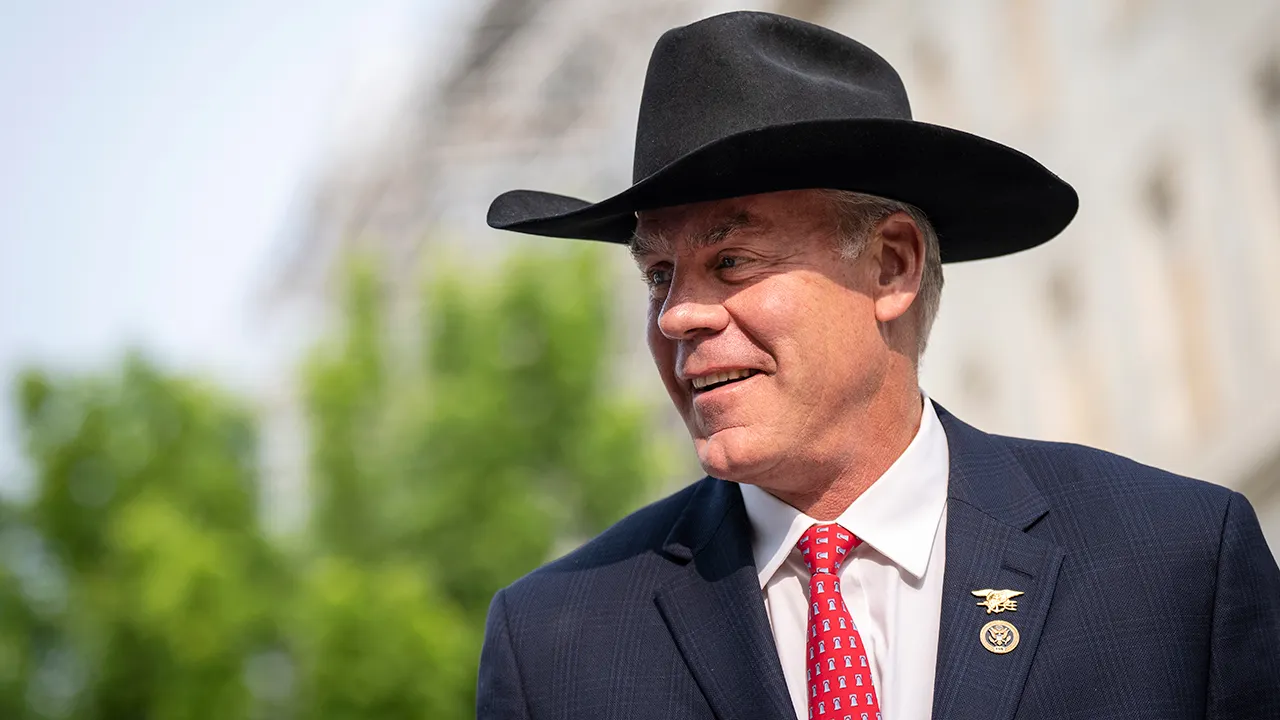

Trump Cabinet alum Ryan Zinke joins mass exodus of lawmakers leaving Congress

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Another House Republican has announced he is retiring from Congress at the end of this year, adding to the mass exodus of lawmakers heading for the exit halfway through President Donald Trump’s second term.

Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Mont., who won his seat in Montana’s 1st congressional district in November 2022, served as Secretary of the Interior during Trump’s first White House stint.

He served as Montana’s only member of the House from 2015 to 2017 before redistricting added a second seat to its delegation.

Zinke is the 35th House Republican elected in 2024 not running for another term in the 2026 midterms. Another House GOP lawmaker re-elected in 2024, the late Rep. Doug LaMalfa, R-Calif., died in office earlier this year.

Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Mont., arrives to a caucus meeting with House Republicans on Capitol Hill, May 10, 2023. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

On the Democratic side, 23 House lawmakers are not running for re-election.

Many of those members are running for another office. But some, including those who left before the end of their terms, like former Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., and Mark Green, R-Tenn., have not made any further public plans in politics.

Zinke had a decades-long career in the U.S. Navy before coming to Congress, achieving the rank of commander before retiring in 2008.

FLORIDA REPUBLICAN REP NEAL DUNN ANNOUNCES RETIREMENT FROM CONGRESS AFTER FIVE TERMS

He cited medical reasons for his decision not to run again in November, according to a letter shared on X.

Zinke cited medical reasons for his decision to retire. (Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call, Inc. via Getty Images)

“While my belief in term limits for elected office is a consideration, I have quietly undergone multiple surgeries since I returned to Congress and unfortunately face several more immediately after leaving office,” Zinke said in his statement.

“The injuries sustained from a career in Special Operations are not immediately life-threatening, but the repair cannot be deferred any longer and recovery will require considerable time with my wife Lola and my family. My judgment and experience tell me it is better for Montana and America to have full-time representation in Congress than run the risk of uncertain absence and missed votes.”

He said serving Montana in his various military and political roles has been the “highest honor.”

JOHNSON WARNS HOUSE REPUBLICANS TO ‘STAY HEALTHY’ AS GOP MAJORITY SHRINKS TO THE EDGE

President Donald Trump and first lady Melania Trump walk out of the White House to travel to the U.S. Capitol where he delivered the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress in the House chamber in Washington, Feb. 24, 2026. (Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP Photo)

Rep. Troy Downing, R-Mont., also confirmed Zinke’s retirement in his own statement shared with media.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

“For over 30 years, Commander Zinke has served his country with integrity, responsibility, and honor,” Downing said. “It has been the privilege of a lifetime to serve alongside Ryan while fighting for Montanans in Washington—from protecting our public lands to supporting our farmers and ranchers.”

The nonpartisan Cook Political Report rates Zinke’s seat R+5, meaning it’s likely to stay in Republican hands but within striking distance for Democrats hoping to flip the district this year.

Read the full article from Here

San Francisco, CA

Grocery Outlet to close dozens of stores after overexpansion

The Bay Area-based bargain grocer Grocery Outlet is closing 36 stores after it expanded too fast.

The closures are part of an optimization plan that will target financially underperforming locations as well as a distribution center facility that’s no longer in use. The closures will go into effect by the end of this year, the company’s chief executive said in an earnings call Wednesday.

Grocery giants Kroger and Albertsons also closed several locations last year and laid off hundreds of employees as inflationary pressures hit consumers and rising labor costs tightened margins.

Kroger, the parent company of California staples Ralphs and Food 4 Less, has been restructuring since a failed merger with Albertsons in 2024.

Grocery Outlet Chief Executive Jason Potter did not say there would be layoffs associated with the store closures.

“Following a rigorous analysis of the fleet, we identified 36 stores in the network that we concluded did not have a viable path to sustained profitability,” Potter said in the company’s latest earnings call. “It’s clear now that we expanded too quickly, and these closures are a direct correction.”

The company is still planning to open 30 to 33 new stores this year. It reported a net loss of $225 million for fiscal year 2025, compared to a net income of $39 million in 2024. Net sales increased 7.3% from 2024 to 2025.

In the fourth quarter of 2025, the company reported a net loss of $218 million. Shares have fallen more than 43% over the past year.

“We made progress on our strategic priorities in 2025; however, our fourth-quarter results made clear that we have more work to do,” Potter said.

Based in Emeryville, Grocery Outlet and its subsidiaries have more than 560 stores in 16 states, including California and Washington. Among the 36 stores slated for closure, 24 are in the eastern U.S. region.

Grocery Outlet locations are independently operated and geared toward affordability, targeting a value-seeking customer base. The chain has more than 100 locations in California, including several in the Los Angeles area.

The company’s new optimization plan is intended to “strengthen long-term profitability and cash flow generation, improve operational execution, optimize our existing store footprint and align with our disciplined new store growth strategy,” the company’s earnings release said.

The company estimated that its fiscal 2026 gross profit could be negatively impacted by $4 million to $6 million due to product markdowns at stores marked for closure.

Denver, CO

Sinclair makes procedure changes after fuel contamination incident in Denver metro area

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin5 days ago

Wisconsin5 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts4 days ago

Massachusetts4 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Maryland6 days ago

Maryland6 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida6 days ago

Florida6 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon1 week ago

Oregon1 week ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling