Science

Hours on hold, limited appointments: Why California babies aren’t going to the doctor

Maria Mercado’s 5- and 7-year-old daughters haven’t been to the doctor for a check-up in two years. And it’s not for lack of trying.

Mercado, a factory worker in South Los Angeles, has called the pediatrician’s office over and over hoping to book an appointment for a well-child visit, only to be told there are no appointments available and to call back in a month. Sometimes, she waits on hold for an hour. Like more than half of children in California, Mercado’s daughters have Medi-Cal, the state’s health insurance program for low-income residents.

Her children are two years behind on their vaccinations. Mercado isn’t sure if they’re growing well, and they haven’t been screened for vision, hearing or developmental delays. Her older daughter has developed a stutter, and she worries the girl might need speech therapy.

“It is frustrating because as a mom, you want your kids to hit every milestone,” she said. “And if you see something’s going on and they’re not helping you, it’s like, what am I supposed to do at this point?”

Faye Holmes with 4-year-old sons Robbie, left, and JoJo, right, waits for a nurse to administer shots.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

California — where 97% of children have health insurance — ranks 46th out of all 50 states and the District of Columbia for providing a preventive care visit for kids 5 and under, according to a 2022 federal government survey. A recent report card from Children Now, a nonprofit advocacy group, rated California a D on children’s access to preventive care, despite the state’s A- grade for ensuring children have coverage.

The majority of California’s youngest residents — including 1.4 million children ages 5 and under — rely on Medi-Cal, an infrastructure ill-equipped to serve them. The state has been criticized in two consecutive audits in the past five years for failing to hold Medi-Cal insurance plans accountable for providing the necessary preventive care to the children they are paid to cover.

In a written response to questions from The Times, the Department of Health Care Services, the state agency in charge of the Medi-Cal program, said “improving children’s preventive care is one of DHCS’ top priorities,” and that the agency has recently addressed most of the shortcomings identified in the audits.

The department’s focus on the pandemic slowed action on the audit findings, the response said. State healthcare officials have since begun to more harshly fine plans that don’t provide adequate care and substantially boost payments to pediatricians to help increase access.

But information released publicly this month by the department suggests serious problems remain.

“In the whole scheme of the U.S. health system, I hate to say it, the youngest kids are always the ones that are overlooked,” said Dr. Alice Kuo, a pediatrician and health policy professor at UCLA.

According to state Medi-Cal data from 2021, the most recent year for which detailed data are available, and assessments from health experts, the impact is sobering:

- 60% of babies did not get their recommended well-child visits in the first 15 months of life. Access was even worse for Black babies — 75% did not receive their recommended screenings. Children who do not attend their well-child visits are more likely to go to the emergency room and be hospitalized for illnesses like asthma.

- 65% of 2-year-olds were not fully vaccinated, leaving them vulnerable to preventable diseases like measles and whooping cough.

- Half of children did not receive a lead screening by their second birthday; families may not know if their homes or other environments are unsafe, which raises the potential for irreversible damage.

- 71% of children did not receive their recommended developmental screening in their first three years. Without routine screenings, less than half of children with developmental or behavioral disorders are detected before kindergarten and miss out on early interventions.

“There’s a lot that happens in a well-child visit that keeps the child healthy in the immediate and the long term,” said Dr. Yasangi Jayasinha, a pediatrician with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. A doctor must ensure that a child is growing and developing normally, getting the proper nutrition, and help the family get plugged into other needed resources like food and housing assistance.

Anthony Serrano’s mother, Alexia Peralta, spent months in limbo trying to get her son re-enrolled in Medi-Cal.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“No state is perfect, but it is particularly concerning that California isn’t at least in the middle of the pack, given its focus on young children and the importance of early brain development,” said Elisabeth Wright Burak, who studies child health policy at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s Center for Children and Families.

A growing problem

There are myriad reasons for California’s poor rates of preventive care for children, according to health experts across the state: a shortage of pediatricians who accept Medi-Cal, especially in rural parts of the state; transportation issues for families who don’t have a car; difficulties getting time off work to take a child to a doctor’s appointment; a byzantine Medi-Cal bureaucracy that makes coverage difficult to use for patients.

In 2019, a California State Auditor report found that less than half of children with Medi-Cal received their recommended preventive care. The audit blamed low reimbursement rates to Medi-Cal physicians, as well as poor state oversight, and gave the department a list of fixes.

Three years later, the auditor released a follow-up report, saying that the department had failed to fully implement eight of the 14 recommendations, including making sure directories of available providers are accurate and requiring health plans to address barriers to care.

The 2022 report found access had grown even worse, a decline largely attributed to the pandemic. Just 42% of children in Medi-Cal received their recommended preventive care. An average of 2.9 million children were missing out on care each year.

For the youngest children the results were particularly troubling: 60% of 1-year-olds and 73% of 2-year-olds in Medi‑Cal did not receive the required number of preventive services.

Although federal law requires that families have access to primary care within 10 miles or 30 minutes of their home, the health department had issued more than 10,000 exceptions. In Monterey County, for example, a healthcare plan requires families to travel up to 58 miles to see a pediatrician.

The department has since implemented all but one of the recommendations it agreed to, and is in the process of overhauling the Medi-Cal program, the response said. This includes beginning to levy higher fines against Medi-Cal plans that do not provide recommended well-child visits, vaccinations and lead screenings to enough children.

A spokesperson for the state auditor’s office said the department has not proved that it has implemented three of the recommendations.

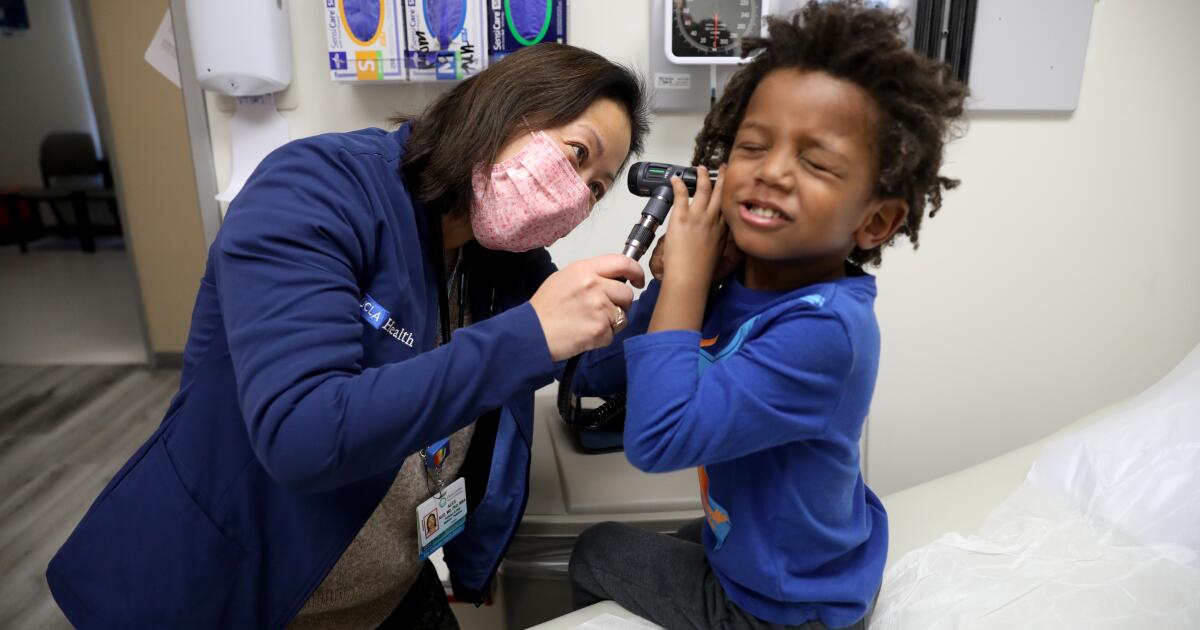

Dr. Alice Kuo performs a well-child visit with 4-year-old patients Robbie, left, and JoJo, with help from their mother, Faye Holmes.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times)

This month, the department announced assessments and fines for 2022. While DHCS reported some progress on access to well-child visits, the plans continued to struggle overall, and the quality of children’s healthcare lagged behind measures for other types of care, including behavioral health and chronic disease management.

Only one plan met all of the minimum standards on children’s health: Community Health Group Partnership Plan in San Diego. Eighteen out of 25 plans were fined $25,000-$890,000 for poor performance, including for children’s health.

Long waits, long drives

Parents and advocates say getting care for children remains a daily challenge. About 11 million Californians live in a primary care shortage area, where a pediatrician can be difficult to find.

“It’s most of the state, not just the Central Valley,” said Kathryn E. Phillips, an associate director at the California Health Care Foundation. California has not trained enough new doctors to meet the needs of the population, she said, and the current workforce is aging. In rural areas in particular, it can be difficult to recruit new pediatricians to join a practice.

Historically, Medi-Cal has paid doctors far less than other insurers, and the program has struggled to find enough willing to accept the rates. In 2021, for example, Medi-Cal paid $37 for a checkup with a toddler.

For the record:

2:27 p.m. Feb. 26, 2024An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the name of pediatrician Eric Ball as Eric Bell.

“Medi-Cal patients basically don’t keep the lights on. You can’t make ends meet,” said Dr. Eric Ball, a pediatrician in Orange County. About a quarter of his patients have Medi-Cal, but the practice stays afloat because of payments from privately insured patients. That may change as the state has increased the Medi-Cal rates significantly this year, up to $116 for a toddler checkup.

In Los Angeles, families often face long wait times to get an appointment with a Medi-Cal provider— 82% of children in the county did not receive a developmental screening in the first three years, 2020 state data showed.

At UCLA, Kuo said patients at her practice must book their well-child visits three to six months in advance. “We get patients coming from Palm Springs to UCLA because there’s no access.”

Are you a SoCal mom?

The L.A. Times early childhood team wants to connect with you! Find us in The Mamahood’s mom group on Facebook.

Share your perspective and ask us questions.

Many Californians — especially those with low incomes — can’t afford the costs or time to make such a long drive, especially for the multiple visits recommended each year for a baby or toddler. Medi-Cal provides a transportation benefit to members, but many families don’t know it exists or say it is difficult to arrange.

“Families are so stressed about housing. They’re stressed about the price of gas. The cost of living here is so high,” said Dr. Lisa Chamberlain, a professor of pediatrics at the Stanford School of Medicine. A doctor’s visit for a seemingly healthy child is “just not going to make it to the top of the list.”

Rosa Benito, 21, lives with her parents and five siblings in Thermal, a town in Riverside County, where the family works in agricultural fields. Getting her siblings to the doctor is a constant struggle.

“We just have my dad and his little gray car, ” she said. The family goes to a clinic in Moreno Valley, over an hour away, but it’s only open during the workday, and their farming jobs don’t offer sick time. Taking a child to the doctor means missing work, which they can’t afford.

And since her parents lack documentation to be in the country legally, they’re scared of the long travel to the clinic for fear that they’ll be pulled over by Border Patrol. “It just turns into a bigger problem. The kids would be without a guardian,” explained Benito. Unless there’s an emergency, the trip often isn’t worth it.

Luz Gallegos of TODEC, a legal center in the Inland Empire serving immigrants and farmworkers, said many families stick with traditional “remedios” for their children and only bring them to the doctor for vaccines when it’s time to enroll in kindergarten. Some have lingering fears that using their child’s Medi-Cal benefits could affect their immigration status.

“Our families don’t think about prevention. They think about surviving.”

The Medi-Cal problem

While family challenges can play a role in missed visits, the state auditor found that the blame for California’s poor performance fell largely on the Medi-Cal program.

“By failing to prioritize implementing our recommendations, DHCS has… left certain children at risk of lifelong health consequences,” the auditors wrote in their 2022 report.

Celia Valdez, director of health outreach and navigation at Maternal Child Health Access, an L.A. nonprofit that manages several social service programs, says they hear daily from families who don’t know how to navigate the Medi-Cal bureaucracy: missing insurance cards, an unexplained switch in their assigned pediatrician, coverage that is suddenly terminated. “People are lost, and by the time they get to someone who can help them, critical time has passed,” said Valdez.

Alexia Peralta kisses her son, Anthony Serrano, at their apartment in Hawthorne. A nonprofit helped her re-enroll Anthony in Medi-Cal after seven months in limbo.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

For Alexia Peralta of Hawthorne, the problems started about two months after her son was born last year, when his Medi-Cal enrollment went awry. She tried to book his 4-month well-child visit and was told he didn’t have coverage; she would have to pay $145 for the visit — an impossible sum.

She spent seven months in limbo — calling Medi-Cal repeatedly, waiting on hold for hours to speak with someone in Spanish, only to be disconnected. Several times, she thought she’d solved the problem, only to get to the pediatrician’s office and be turned away.

“I feel frustrated, mad and sad. I tried to get all these things for my child and got the run-around,” she said. He missed both his 4-month and 6-month vaccines.

Eventually, with the help of a home visitor from a Shields for Families program, a nonprofit in L.A., Peralta was able to get her son re-enrolled. At 15 months, he is still catching up on his vaccines.

Trying to fix the system

The health department said the challenges are not unique to California, and that the pandemic “resulted in large backlogs of children who needed to catch up on preventive services, a worsening crisis in the health care workforce, and limited additional capacity for pediatric services.”

In response, the department “has made historic investments and launched new initiatives” that “look to lift our youngest Californians and allow them to be healthy and to thrive.” This includes sending educational materials to families about recommended care, creating new contracts with Medi-Cal plans that more closely track children’s healthcare, and continuing to fine plans that fail to perform.

The state is also pumping money into the primary care workforce and is expanding residency and loan repayment programs. There are new Medi-Cal benefits to pay for doulas and community health workers, who can help patients navigate care, the response said.

Sayra Peralta dances with her grandson, Anthony Serrano, as her daughter, Alexia Peralta, looks on.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“The big ship is slowly turning,” said Mike Odeh, senior director of health at Children Now, who serves in an advisory group for the department. “But I want to emphasize how big the ship is and how hard it is to turn, given that we have decades of plans not providing care for kids. Changing that is going to take a lot of work.”

Former State Sen. Richard Pan, who was chair of the Health Committee before terming out in 2022, said he is not yet convinced the department’s response to the audits has been adequate. The devil is in the details, he said — are the fines against plans high enough? And how many plans will end up complying?

“Give us the proof that it’s been fixed. Show us the data. Unfortunately, I’m not in a position now to hold hearings, but I think that’s the next follow through,” he said. “The buck should always stop at the state.”

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

Science

Newsom tells world leaders Trump’s retreat on the environment will mean economic harm

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Gavin Newsom told world leaders Friday that President Trump’s retreat from efforts to combat climate change would decimate the U.S. automobile industry and surrender the future economic viability to China and other nations embracing the transition to renewable energy.

Newsom, appearing at the Munich Security Conference in Germany, urged diplomats, business leaders and policy advocates to forcefully stand up to Trump’s global bullying and loyalty to the oil and coal industry. The California governor said the Trump administration’s massive rollbacks on environmental protection will be short-lived.

“Donald Trump is temporary. He’ll be gone in three years,” Newsom said during a Friday morning panel discussion on climate action. “California is a stable and reliable partner in this space.”

Newsom’s comments came in the wake of the Trump administration’s repeal of the endangerment finding and all federal vehicle emissions regulations. The endangerment finding is the U.S. government’s 2009 affirmation that planet-heating pollution poses a threat to human health and the environment.

Environmental Protection Agency administrator Lee Zeldin said the finding has been regulatory overreach, placing heavy burdens on auto manufacturers, restricting consumer choice and resulting in higher costs for Americans. Its repeal marked the “single largest act of deregulation in the history of the United States of America,” he said.

Scientists and experts were quick to condemn the action, saying it contradicts established science and will put more people in harm’s way. Independent researchers around the world have long concluded that greenhouse gases released by the burning of gasoline, diesel and other fossil fuels are warming the planet and worsening weather disasters.

The move will also threaten the U.S.’s position as a leader in the global clean energy transition, with nations such as China pulling ahead on electric vehicle production and investments in renewables such as solar, batteries and wind, experts said.

Newsom’s trip to Germany is just his latest international jaunt in recent months as he positions himself to lead the Democratic Party’s opposition to Trump and the Republican-led Congress, and to seed a possible run for the White House in 2028. Last month Newsom traveled to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and in November to the U.N. climate summit in Belém, Brazil — mocking and condemning Trump’s policies on Greenland, international trade and the environment.

When asked how he would restore the world’s confidence in the United States if he were to become president, Newsom sidestepped. Instead he offered a campaign-like soliloquy on California’s success on fostering Tesla and the nation’s other top electric vehicle manufacturers as well as being a magnet for industries spending billions of dollars on research and development for the global transition away from carbon-based economies.

The purpose of the Munich conference was to open a dialogue among world leaders on global security, military, economic and environmental issues. Along with Friday’s discussion on climate action, Newsom is scheduled to appear at a livestreamed forum on transatlantic cooperation Saturday.

Andrew Forrest, executive chairman of the Australia-based mining company giant Fortescue, said during a panel Friday his company is proof that even the largest energy-consuming companies in the world can thrive without relying on the carbon-based fuels that have driven industries for more than a century. Fortescue, which buys diesel fuel from countries across the world, will transition to a “green grid” this decade, saving the company a billion dollars a year, he said.

“The science is absolutely clear, but so is the economics. I am, and my company Fortescue is, the industrial-grade proof that going renewable is great economics, great business, and if you desert it, then in the end, you’ll be sorted out by your shareholders or by your voters at the ballot box,” Forrest said.

Newsom said California has also shown the world what can be done with innovative government policies that embrace electric vehicles and the transition to a non-carbon-based economy, and continues to do so despite the attacks and regressive mandates being imposed by the Trump administration.

“This is about economic prosperity and competitiveness, and that’s why I’m so infuriated with what Donald Trump has done,” Newsom said. “Remember, Tesla exists for one reason — California’s regulatory market, which created the incentives and the structure and the certainty that allowed Elon Musk and others to invest and build that capacity. We are not walking away from that.”

California has led the nation in the push toward EVs. For more than 50 years, the state enjoyed unique authority from the EPA to set stricter tailpipe emission standards than the federal government, considered critical to the state’s efforts to address its notorious smog and air-quality issues. The authority, which the Trump administration has moved to rescind, was also the basis for California’s plan to ban the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035.

The administration again targeted electric vehicles in its announcement on Thursday.

“The forced transition to electric vehicles is eliminated,” Zeldin said. “No longer will automakers be pressured to shift their fleets toward electric vehicles, vehicles that are still sitting unsold on dealer lots all across America.”

But the efforts to shut down the energy transition may be too little, too late, said Hannah Safford, former director of transportation and resilience at the White House Climate Policy Office under the Biden administration.

“Electric cars make more economic sense for people, more models are becoming available, and the administration can’t necessarily stop that from happening,” said Safford, who is now associate director for climate and environment at the Federation of American Scientists.

Still, some automakers and trade groups supported the EPA’s decision, as did fossil fuel industry groups and those geared toward free markets and regulatory reform. Among them were the Independent Petroleum Assn. of America, which praised the administration for its “efforts to reform and streamline regulations governing greenhouse gas emissions.”

Ford, which has invested in electric vehicles and recently completed a prototype of a $30,000 electric truck, said in a statement to The Times that it appreciated EPA’s move “to address the imbalance between current emissions standards and consumer choice.”

Toyota, meanwhile, deferred to a statement from Alliance for Automotive Innovation president John Bozzella, who said similarly that “automotive emissions regulations finalized in the previous administration are extremely challenging for automakers to achieve given the current marketplace demand for EVs.”

Science

Judge blocks Trump administration move to cut $600 million in HIV funding from states

A federal judge on Thursday blocked a Trump administration order slashing $600 million in federal grant funding for HIV programs in California and three other states, finding merit in the states’ argument that the move was politically motivated by disagreements over unrelated state sanctuary policies.

U.S. District Judge Manish Shah, an Obama appointee in Illinois, found that California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota were likely to succeed in arguing that President Trump and other administration officials targeted the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding for termination “based on arbitrary, capricious, or unconstitutional rationales.”

Namely, Shah wrote that while Trump administration officials said the programs were cut for breaking with CDC priorities, other “recent statements” by officials “plausibly suggest that the reason for the direction is hostility to what the federal government calls ‘sanctuary jurisdictions’ or ‘sanctuary cities.’”

Shah found that the states had shown they would “suffer irreparable harm” from the cuts, and that the public interest would not be harmed by temporarily halting them — and as a result granted the states a temporary restraining order halting the administration’s action for 14 days while the litigation continues.

Shah wrote that while he may not have jurisdiction to block a simple grant termination, he did have jurisdiction to halt an administration directive to terminate funding based on unconstitutional grounds.

“More factual development is necessary and it may be that the only government action at issue is termination of grants for which I have no jurisdiction to review,” Shah wrote. “But as discussed, plaintiffs have made a sufficient showing that defendants issued internal guidance to terminate public-health grants for unlawful reasons; that guidance is enjoined as the parties develop a record.”

The cuts targeted a slate of programs aimed at tracking and curtailing HIV and other disease outbreaks, including one of California’s main early-warning systems for HIV outbreaks, state and local officials said. Some were oriented toward serving the LGBTQ+ community. California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office said California faced “the largest share” of the cuts.

The White House said the cuts were to programs that “promote DEI and radical gender ideology,” while federal health officials said the programs in question did not reflect the CDC’s “priorities.”

Bonta cheered Shah’s order in a statement, saying he and his fellow attorneys general who sued are “confident that the facts and the law favor a permanent block of these reckless and illegal funding cuts.”

Science

Contributor: Is there a duty to save wild animals from natural suffering?

The internet occasionally erupts in horror at disturbing images of wildlife: deer with freakish black bubbles all over their faces and bodies, sore-ridden squirrels, horn-growing rabbits.

As a society, we tend to hold romanticized notions about life in the wild. We picture these rabbits nuzzling with their babies, these squirrels munching on some nuts and these deer frolicking through sunlit meadows. Yet the trend of Frankenstein creatures afflicted with various diseases is steadily peeling back this idyllic veneer, revealing the harsher realities that underpin the natural world. And we should do something about it.

First, consider that wild animals — the many trillions of them — aren’t so different from other animals we care about — like dogs and cats — or even from us. They love. They build complex social structures. They have emotions. And most important, they too experience suffering.

Many wild animals are suffering because of us. We destroy their habitats, they’re sterilized and killed by our pollution, and sometimes we hunt them down as trophies. Suffering created by humans is especially galling.

But even in the absence of human impact, wild animals still experience a great deal of pain. They starve and thirst. They get infected by parasites and diseases. They’re ripped apart by other animals. Some of us have bought into the naturalistic fallacy that interfering with nature is wrong. But suffering is suffering wherever it occurs, and we should do something about it when we can. If we have the opportunity to rescue an injured or ill animal, why wouldn’t we? If we can alleviate a being’s suffering, shouldn’t we?

If we accept that we do have an obligation to help wild animals, where should we start? Of course, if we have an obvious opportunity to help an animal, like a bird with a broken wing, we ought to step in, maybe take it to a wildlife rescue center if there are any nearby. We can use fewer toxic products and reduce our overall waste to minimize harmful pollution, keep fresh water outside on hot summer days, reduce our carbon footprint to prevent climate-change-induced fires, build shelter for wildlife such as bats and bees, and more. Even something as simple as cleaning bird feeders can help reduce rates of disease in wild animals.

And when we do interfere in nature in ways that affect wild animals, we should do so compassionately. For example, in my hometown of Staten Island, in an effort to combat the overpopulation of deer (due to their negative impact on humans), officials deployed a mass vasectomy program, rather than culling. And it worked. Why wouldn’t we opt for a strategy that doesn’t require us to put hundreds of innocent animals to death?

But nature is indifferent to suffering, and even if we do these worthy things, trillions will still suffer because the scale of the problem is so large — literally worldwide. It’s worth looking into the high-level changes we can make to reduce animal suffering. Perhaps we can invest in the development and dissemination of cell-cultivated meat — meat made from cells rather than slaughtered animals — to reduce the amount of predation in the wild. Gene-drive technology might be able to make wildlife less likely to spread diseases such as the one afflicting the rabbits, or malaria. More research is needed to understand the world around us and our effect on it, but the most ethical thing to do is to work toward helping wild animals in a systemic way.

The Franken-animals that go viral online may have captured our attention because they look like something from hell, but their story is a reminder that the suffering of wild animals is real — and it is everywhere. These diseases are just a few of the countless causes of pain in the lives of trillions of sentient beings, many of which we could help alleviate if we chose to. Helping wild animals is not only a moral opportunity, it is a responsibility, and it starts with seeing their suffering as something we can — and must — address.

Brian Kateman is co-founder of the Reducetarian Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reducing consumption of animal products. His latest book and documentary is “Meat Me Halfway.”

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- Wild animals experience genuine suffering comparable to that of domesticated animals and humans, including through starvation, disease, parasitism, and predation, and society romanticizes wildlife in ways that obscure these harsh realities[1][2]

- Humans have a moral obligation to address wild animal suffering wherever possible, as suffering is morally significant regardless of whether it occurs naturally or results from human action[2]

- Direct intervention in individual cases is warranted, such as rescuing injured animals or providing fresh water during heat waves, alongside broader systemic approaches like reducing pollution and carbon emissions[2]

- Humane wildlife management strategies should be prioritized over lethal approaches when addressing human-wildlife conflicts, as demonstrated by vasectomy programs that manage overpopulation without mass culling[2]

- Large-scale technological solutions, including cell-cultivated meat to reduce predation and gene-drive technology to control disease transmission, should be pursued and researched to systematically reduce wild animal suffering at scale[2]

- The naturalistic fallacy—the belief that natural processes should never be interfered with—is fundamentally flawed when weighed against the moral imperative to alleviate suffering[2]

Different views on the topic

The search results provided do not contain explicit opposing viewpoints to the author’s argument regarding a moral duty to intervene in wild animal suffering. The available sources focus primarily on the author’s work on reducing farmed animal consumption through reducetarianism and factory farming advocacy[1][3][4], rather than perspectives that directly challenge the premise that humans should work to alleviate wild animal suffering through technological or ecological intervention.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Alabama6 days ago

Alabama6 days agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

San Francisco, CA1 week ago

San Francisco, CA1 week agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Ohio1 week ago

Ohio1 week agoOhio town launching treasure hunt for $10K worth of gold, jewelry

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoIs Emily Brontë’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ Actually the Greatest Love Story of All Time?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe Long Goodbye: A California Couple Self-Deports to Mexico

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump admin sued by New York, New Jersey over Hudson River tunnel funding freeze: ‘See you in court’

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoTuberculosis outbreak reported at Catholic high school in Bay Area. Cases statewide are climbing