Alaska

Small Alaskan town plagued by a foul chartreuse menace

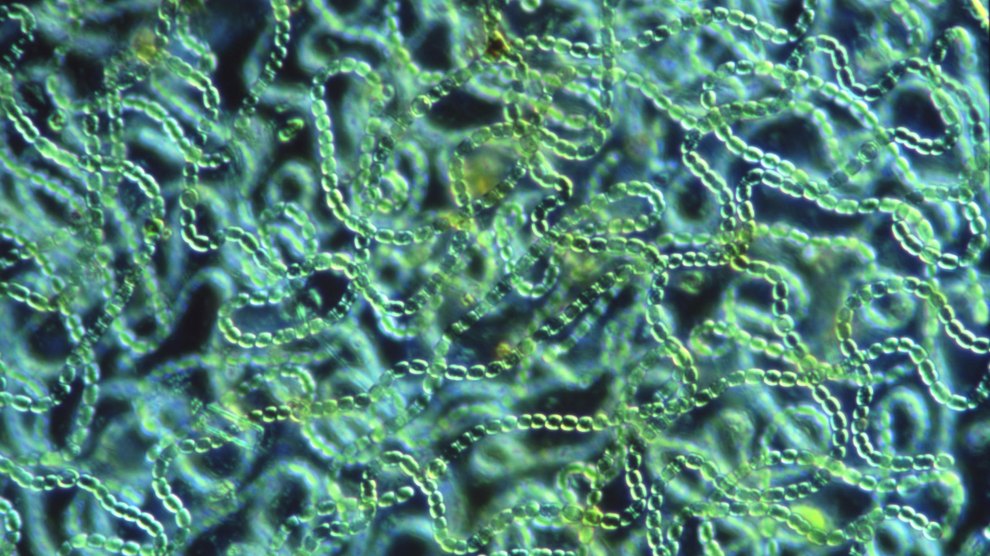

Cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, are fairly below a microscope however devastating to marine ecosystems.M. I. Walker/UPPA through ZUMA

This story was initially printed by Hakai and is reproduced right here as a part of the Local weather Desk collaboration.

Lifeless fish had been in every single place, speckling the seaside close to city and lengthening onto the encircling shoreline. The sheer magnitude of the October 2021 die-off, when tons of, presumably hundreds, of herring washed up, is what sticks within the minds of the residents of Kotzebue, Alaska. Fish had been “actually all around the seashores,” says Bob Schaeffer, a fisherman and elder from the Qikiqtaġruŋmiut tribe.

Regardless of the dramatic deaths, there was no obvious wrongdoer. “We do not know what brought about it,” says Alex Whiting, the environmental program director for the Native Village of Kotzebue. He wonders if the die-off was a symptom of an issue he’s had his eye on for the previous 15 years: blooms of poisonous cyanobacteria, generally known as blue-green algae, which have turn out to be more and more noticeable within the waters round this distant Alaska city.

Kotzebue sits about 40 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, on Alaska’s western shoreline. Earlier than the Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue had his identify connected to the place within the 1800s, the area was known as Qikiqtaġruk, which means “place that’s virtually an island.” One facet of the two-kilometer-long settlement is bordered by Kotzebue Sound, an offshoot of the Chukchi Sea, and the opposite by a lagoon. Planes, boats, and four-wheelers are the principle modes of transportation. The one highway out of city merely loops across the lagoon earlier than heading again in.

In the course of city, the Alaska Business Firm sells meals that’s widespread within the decrease 48—from cereal to apples to two-bite brownies—however the ocean is the true grocery retailer for many individuals on the town. Alaska Natives, who make up about three-quarters of Kotzebue’s inhabitants, pull tons of of kilograms of meals out of the ocean yearly.

“We’re ocean folks,” Schaeffer tells me. The 2 of us are crammed into the tiny cabin of Schaeffer’s fishing boat within the just-light hours of a drizzly September 2022 morning. We’re motoring towards a water-monitoring system that’s been moored in Kotzebue Sound all summer season. On the bow, Ajit Subramaniam, a microbial oceanographer from Columbia College, New York, Whiting, and Schaeffer’s son Vince have their noses tucked into upturned collars to defend towards the chilly rain. We’re all there to gather a summer season’s price of details about cyanobacteria that may be poisoning the fish Schaeffer and plenty of others rely upon.

Big colonies of algae are nothing new, they usually’re usually helpful. Within the spring, for instance, elevated mild and nutrient ranges trigger phytoplankton to bloom, making a microbial soup that feeds fish and invertebrates. However not like many types of algae, cyanobacteria could be harmful. Some species can produce cyanotoxins that trigger liver or neurological injury, and maybe even most cancers, in people and different animals.

Many communities have fallen foul of cyanobacteria. Though many cyanobacteria can survive within the marine atmosphere, freshwater blooms are likely to garner extra consideration, and their results can unfold to brackish environments when streams and rivers carry them into the ocean. In East Africa, for instance, blooms in Lake Victoria are blamed for enormous fish kills. Individuals may also endure: in an excessive case in 1996, 26 sufferers died after receiving remedy at a Brazilian hemodialysis middle, and an investigation discovered cyanotoxins within the clinic’s water provide. Extra usually, people who find themselves uncovered expertise fevers, complications, or vomiting.

When phytoplankton blooms decompose, complete ecosystems can take a success. Rotting cyanobacteria rob the waters of oxygen, suffocating fish and different marine life. Within the brackish waters of the Baltic Sea, cyanobacterial blooms contribute to deoxygenation of the deep water and hurt the cod business.

As local weather change reshapes the Arctic, no person is aware of how—or if—cyanotoxins will have an effect on Alaskan folks and wildlife. “I strive to not be alarmist,” says Thomas Farrugia, coordinator of the Alaska Dangerous Algal Bloom Community, which researches, displays, and raises consciousness of dangerous algal blooms across the state. “However it’s one thing that we, I believe, are simply not fairly ready for proper now.” Whiting and Subramaniam need to change that by determining why Kotzebue is taking part in host to cyanobacterial blooms and by making a speedy response system that might ultimately warn locals if their well being is in danger.

Cyanobacteria within the Baltic Sea.

Joshua Stevens/NASA

Whiting’s cyanobacteria story began in 2008. Someday whereas using his bike house from work, he got here throughout an arresting web site: Kotzebue Sound had turned chartreuse, a colour not like something he thought existed in nature. His first thought was, The place’s this paint coming from?

The story of cyanobacteria on this planet goes again about 1.9 billion years, nevertheless. As the primary organisms to evolve photosynthesis, they’re usually credited with bringing oxygen to Earth’s environment, clearing the trail for advanced life kinds resembling ourselves.

Over their lengthy historical past, cyanobacteria have advanced methods that permit them proliferate wildly when shifts in circumstances resembling nutrient ranges or salinity kill off different microbes. “You may consider them as form of the weedy species,” says Raphael Kudela, a phytoplankton ecologist on the College of California, Santa Cruz. Most microbes, for instance, want a posh type of nitrogen that’s generally solely out there in restricted portions to develop and reproduce, however the predominant cyanobacteria in Kotzebue Sound can use a easy type of nitrogen that’s present in just about limitless portions within the air.

Cyanotoxins are probably one other software that assist cyanobacteria thrive, however researchers aren’t certain precisely how toxins profit these microbes. Some scientists assume they deter organisms that eat cyanobacteria, resembling greater plankton and fish. Hans Paerl, an aquatic ecologist from the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, favors one other speculation: that toxins defend cyanobacteria from the doubtless damaging astringent byproducts of photosynthesis.

Across the time when Kotzebue noticed its first bloom, scientists had been realizing that local weather change would probably enhance the frequency of cyanobacterial blooms, and what’s extra, that blooms may unfold from contemporary water—lengthy the main focus of analysis—into adjoining brackish water. Kotzebue Sound’s blooms in all probability type in a close-by lake earlier than flowing into the ocean.

The newest science on cyanobacteria, nevertheless, had not reached Kotzebue in 2008. As a substitute, officers from the Alaska Division of Fish and Recreation examined the chartreuse water for petroleum and its byproducts. The exams got here again damaging, leaving Whiting stumped. “I had zero thought,” he says. It was biologist Lisa Clough, then from East Carolina College and now with the Nationwide Science Basis, with whom Whiting had beforehand collaborated, who instructed he think about cyanobacteria. The next yr, water pattern evaluation confirmed she was appropriate.

In 2017, Subramaniam visited Kotzebue as a part of a analysis group learning sea ice dynamics. When Whiting realized that Subramaniam had a long-standing curiosity in cyanobacteria, “we simply instantly clicked,” Subramaniam says.

The 2021 fish kill redoubled Whiting and Subramaniam’s enthusiasm for understanding how Kotzebue Sound’s microbial ecosystem may have an effect on the city. A pathologist discovered injury to the useless fish’s gills, which can have been attributable to the exhausting, spiky shells of diatoms (a kind of algae), however the reason for the fish kill continues to be unclear. With so most of the city’s residents relying on fish as one in all their meals sources, that makes Subramaniam nervous. “If we don’t know what killed the fish, then it’s very tough to handle the query of, Is it protected to eat?” he says.

Alex Whiting, left, and Ajit Subramaniam put together water-monitoring gear for deployment.

Saima Sidik/Hakai Journal

I watch the newest chapter of their collaboration from a crouched place on the deck of Schaeffer’s precipitously swaying fishing boat. Whiting reassures me that the one-piece flotation swimsuit I’m sporting will save my life if I find yourself within the water, however I’m not eager to check that principle. As a substitute, I maintain onto the boat with one hand and the cellphone I’m utilizing to report video with the opposite whereas Whiting, Subramaniam, and Vince Schaeffer haul up a white-and-yellow contraption they moored within the ocean, rocking the boat within the course of. Lastly, a metallic sphere concerning the diameter of a hula hoop emerges. From it initiatives a meter-long tube that accommodates a cyanobacteria sensor.

The sensor permits Whiting and Subramaniam to beat a limitation that many researchers face: a cyanobacterial bloom is intense however fleeting, so “should you’re not right here on the proper time,” Subramaniam explains, “you’re not going to see it.” In distinction to the remoted measurements that researchers usually depend on, the sensor had taken a studying each 10 minutes from the time it was deployed in June to this chilly September morning. By measuring ranges of a fluorescent compound known as phycocyanin, which is discovered solely in cyanobacteria, they hope to correlate these species’ abundance with adjustments in water qualities resembling salinity, temperature, and the presence of different types of plankton.

Researchers are enthusiastic concerning the work due to its potential to guard the well being of Alaskans, and since it may assist them perceive why blooms happen all over the world. “That type of excessive decision is de facto precious,” says Malin Olofsson, an aquatic biologist from the Swedish College of Agricultural Sciences, who research cyanobacteria within the Baltic Sea. By combining phycocyanin measurements with toxin measurements, the scientists hope to supply a extra full image of the hazards dealing with Kotzebue, however proper now Subramaniam’s precedence is to know which species of cyanobacteria are most typical and what’s inflicting them to bloom.

Farrugia, from the Alaska Dangerous Algal Bloom Community, is worked up about the potential for utilizing comparable strategies in different components of Alaska to realize an general view of the place and when cyanobacteria are proliferating. Exhibiting that the sensor works in a single location “is certainly step one,” he says.

Understanding the situation and potential supply of cyanobacterial blooms is barely half the battle: the opposite query is what to do about them. Within the Baltic Sea, the place fertilizer runoff from industrial agriculture has exacerbated blooms, neighboring nations have put quite a lot of effort into curbing that runoff—and with success, Olofsson says. Kotzebue shouldn’t be in an agricultural space, nevertheless, and as an alternative some scientists have hypothesized that thawing permafrost could launch vitamins that promote blooms. There’s not a lot anybody can do to stop this, wanting reversing the local weather disaster. Some chemical substances, together with hydrogen peroxide, present promise as methods to kill cyanobacteria and convey momentary reduction from blooms with out affecting ecosystems broadly, however to this point chemical therapies haven’t offered everlasting options.

As a substitute, Whiting is hoping to create a speedy response system so he can notify the city if a bloom is popping water and meals poisonous. However this may require build up Kotzebue’s analysis infrastructure. For the time being, Subramaniam prepares samples within the kitchen on the Selawik Nationwide Wildlife Refuge’s workplace, then sends them throughout the nation to researchers, who can take days, generally even months, to investigate them. To make the work safer and sooner, Whiting and Subramaniam are making use of for funding to arrange a lab in Kotzebue and presumably rent a technician who can course of samples in-house. Getting a lab is “in all probability the very best factor that might occur up right here,” says Schaeffer. Subramaniam is hopeful that their efforts will repay throughout the subsequent yr.

Within the meantime, curiosity in cyanobacterial blooms can be popping up in different areas of Alaska. Emma Pate, the coaching coordinator and environmental planner for the Norton Sound Well being Company, began a monitoring program after members of native tribes seen elevated numbers of algae in rivers and streams. In Utqiaġvik, on Alaska’s northern coast, locals have additionally began sampling for cyanobacteria, Farrugia says.

Whiting sees this work as filling a essential gap in Alaskans’ understanding of water high quality. Regulatory companies have but to plan techniques to guard Alaskans from the potential menace posed by cyanobacteria, so “any individual must do one thing,” he says. “We will’t all simply be bumbling round in the dead of night ready for a bunch of individuals to die.” Maybe this sense of self-sufficiency, which has let Arctic folks thrive on the frozen tundra for millennia, will as soon as once more get the job accomplished.

The reporting for this text was partially funded by the Council for the Development of Science Writing Taylor/Blakeslee Mentored Science Journalism Undertaking Fellowship.