Science

Jane Goodall, trailblazing naturalist whose intimate observations of chimpanzees transformed our understanding of humankind, has died

Jane Goodall, the trailblazing naturalist whose intimate observations of chimpanzees in the African wild produced powerful insights that transformed basic conceptions of humankind, has died. She was 91.

A tireless advocate of preserving chimpanzees’ natural habitat, Goodall died on Wednesday morning in California of natural causes, the Jane Goodall Institute announced on its Instagram page.

“Dr. Goodall’s discoveries as an ethologist revolutionized science,” the Jane Goodall Institute said in a statement.

For the record:

5:45 p.m. Oct. 2, 2025An earlier version of this story stated the chimpanzees are “humankind’s closest living ancestors.” They are humans’ closest living relatives, but not our ancestors.

A protege of anthropologist Louis S.B. Leakey, Goodall made history in 1960 when she discovered that chimpanzees, humankind’s closest living relatives, made and used tools, characteristics that scientists had long thought were exclusive to humans.

She also found that chimps hunted prey, ate meat, and were capable of a range of emotions and behaviors similar to those of humans, including filial love, grief and violence bordering on warfare.

In the course of establishing one of the world’s longest-running studies of wild animal behavior at what is now Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park, she gave her chimp subjects names instead of numbers, a practice that raised eyebrows in the male-dominated field of primate studies in the 1960s. But within a decade, the trim British scientist with the tidy ponytail was a National Geographic heroine, whose books and films educated a worldwide audience with stories of the apes she called David Graybeard, Mr. McGregor, Gilka and Flo.

“When we read about a woman who gives funny names to chimpanzees and then follows them into the bush, meticulously recording their every grunt and groom, we are reluctant to admit such activity into the big leagues,” the late biologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote of the scientific world’s initial reaction to Goodall.

But Goodall overcame her critics and produced work that Gould later characterized as “one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements.”

Tenacious and keenly observant, Goodall paved the way for other women in primatology, including the late gorilla researcher Dian Fossey and orangutan expert Birutė Galdikas. She was honored in 1995 with the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal, which then had been bestowed only 31 times in the previous 90 years to such eminent figures as North Pole explorer Robert E. Peary and aviator Charles Lindbergh.

In her 80s she continued to travel 300 days a year to speak to schoolchildren and others about the need to fight deforestation, preserve chimpanzees’ natural habitat and promote sustainable development in Africa. She was in California as part of her speaking tour in the U.S. at the time of her death.

Jane Goodall in Gombe National Park in Tanzania.

(Chase Pickering / Jane Goodall Institute)

Goodall was born April 3, 1934, in London and grew up in the English coastal town of Bournemouth. The daughter of a businessman and a writer who separated when she was a child and later divorced, she was raised in a matriarchal household that included her maternal grandmother, her mother, Vanne, some aunts and her sister, Judy.

She demonstrated an affinity for nature from a young age, filling her bedroom with worms and sea snails that she rushed back to their natural homes after her mother told her they would otherwise die.

When she was about 5, she disappeared for hours to a dark henhouse to see how chickens laid eggs, so absorbed that she was oblivious to her family’s frantic search for her. She did not abandon her study until she observed the wondrous event.

“Suddenly with a plop, the egg landed on the straw. With clucks of pleasure the hen shook her feathers, nudged the egg with her beak, and left,” Goodall wrote almost 60 years later. “It is quite extraordinary how clearly I remember that whole sequence of events.”

When finally she ran out of the henhouse with the exciting news, her mother did not scold her but patiently listened to her daughter’s account of her first scientific observation.

Later, she gave Goodall books about animals and adventure — especially the Doctor Dolittle tales and Tarzan. Her daughter became so enchanted with Tarzan’s world that she insisted on doing her homework in a tree.

“I was madly in love with the Lord of the Jungle, terribly jealous of his Jane,” Goodall wrote in her 1999 memoir, “Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey.” “It was daydreaming about life in the forest with Tarzan that led to my determination to go to Africa, to live with animals and write books about them.”

Her opportunity came after she finished high school. A week before Christmas in 1956 she was invited to visit an old school chum’s family farm in Kenya. Goodall saved her earnings from a waitress job until she had enough for a round-trip ticket.

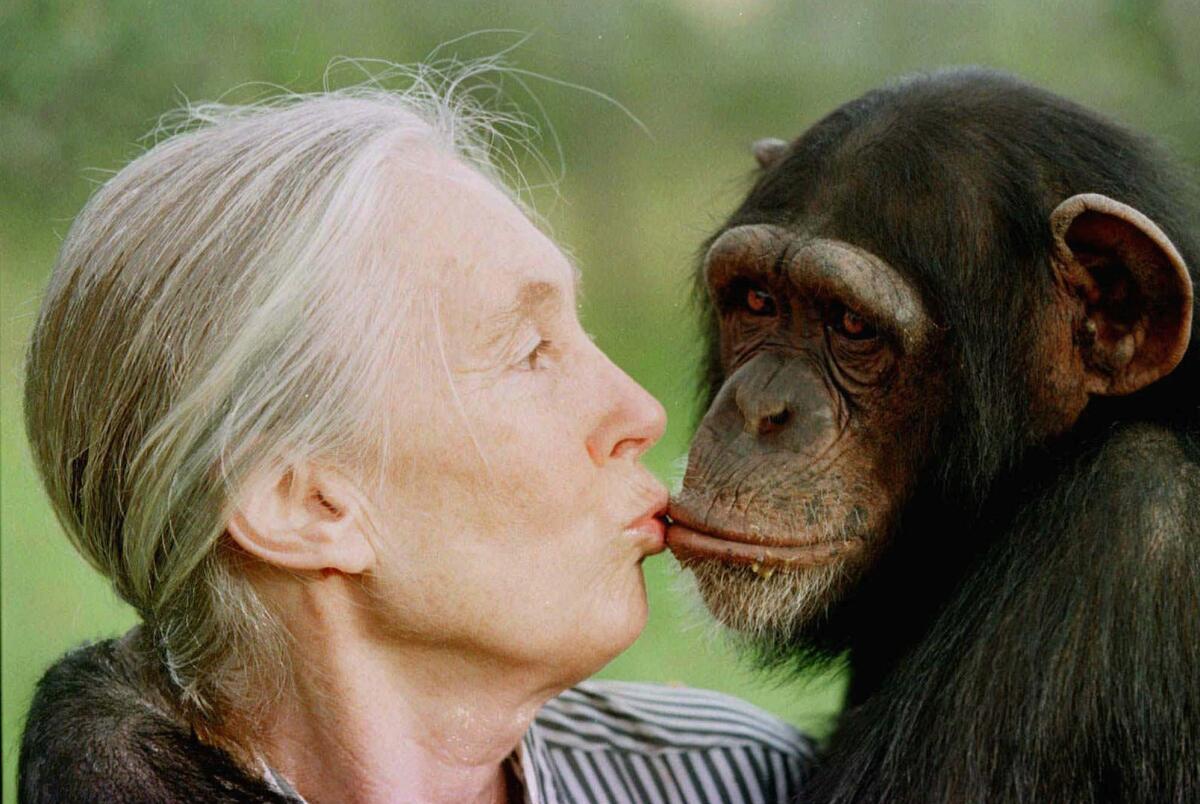

Jane Goodall gives a little kiss to Tess, a 5- or 6-year-old female chimpanzee, in 1997.

(Jean-Marc Bouju / Associated Press)

She arrived in Kenya in 1957, thrilled to be living in the Africa she had “always felt stirring in my blood.” At a dinner party in Nairobi shortly after her arrival, someone told her that if she was interested in animals, she should meet Leakey, already famous for his discoveries in East Africa of man’s fossil ancestors.

She went to see him at what’s now the National Museum of Kenya, where he was curator. He hired her as a secretary and soon had her helping him and his wife, Mary, dig for fossils at Olduvai Gorge, a famous site in the Serengeti Plains in what is now northern Tanzania.

Leakey spoke to her of his desire to learn more about all the great apes. He said he had heard of a community of chimpanzees on the rugged eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika where an intrepid researcher might make valuable discoveries.

When Goodall told him this was exactly the kind of work she dreamed of doing, Leakey agreed to send her there.

It took Leakey two years to find funding, which gave Goodall time to study primate behavior and anatomy in London. She finally landed in Gombe in the summer of 1960.

On a rocky outcropping she called the Peak, Goodall made her first important observation. Scientists had thought chimps were docile vegetarians, but on this day about three months after her arrival, Goodall spied a group of the apes feasting on something pink. It turned out to be a baby bush pig.

Two weeks later, she made an even more exciting discovery — the one that would establish her reputation. She had begun to recognize individual chimps, and on a rainy October day in 1960, she spotted the one with white hair on his chin. He was sitting beside a mound of red earth, carefully pushing a blade of grass into a hole, then withdrawing it and poking it into his mouth.

When he finally ambled off, Goodall hurried over for a closer look. She picked up the abandoned grass stalk, stuck it into the same hole and pulled it out to find it covered with termites. The chimp she later named David Graybeard had been using the stalk to fish for the bugs.

“It was hard for me to believe what I had seen,” Goodall later wrote. “It had long been thought that we were the only creatures on earth that used and made tools. ‘Man the Toolmaker’ is how we were defined …” What Goodall saw challenged man’s uniqueness.

When she sent her report to Leakey, he responded: “We must now redefine man, redefine tool, or accept chimpanzees as human!”

Goodall’s startling finding, published in Nature in 1964, enabled Leakey to line up funding to extend her stay at Gombe. It also eased Goodall’s admission to Cambridge University to study ethology. In 1965, she became the eighth person in Cambridge history to earn a doctorate without first having a bachelor’s degree.

In the meantime, she had met and in 1964 married Hugo Van Lawick, a gifted filmmaker who had traveled to Gombe to make a documentary about her chimp project. They had a child, Hugo Eric Louis — later nicknamed Grub — in 1967.

Goodall later said that raising Grub, who lived at Gombe until he was 9, gave her insights into the behavior of chimp mothers. Conversely, she had “no doubt that my observation of the chimpanzees helped me to be a better mother.”

She and Van Lawick were married for 10 years, divorcing in 1974. The following year she married Derek Bryceson, director of Tanzania National Parks. He died of colon cancer four years later.

Within a year of arriving at Gombe, Goodall had chimps literally eating out of her hands. Toward the end of her second year there, David Graybeard, who had shown the least fear of her, was the first to allow her physical contact. She touched him lightly and he permitted her to groom him for a full minute before gently pushing her hand away. For an adult male chimpanzee who had grown up in the wild to tolerate physical contact with a human was, she wrote in her 1971 book “In the Shadow of Man,” “a Christmas gift to treasure.”

Jane Goodall plays with Bahati, a 3-year-old female chimpanzee, at the Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary, north of Nairobi, on Dec. 6, 1997.

(Jean-Marc Bouju / Associated Press)

Her studies yielded a trove of other observations on behaviors, including etiquette (such as soliciting a pat on the rump to indicate submission) and the sex lives of chimps. She collected some of the most fascinating information on the latter by watching Flo, an older female with a bulbous nose and an amazing retinue of suitors who was bearing children well into her 40s.

Her reports initially caused much skepticism in the scientific community. “I was not taken very seriously by many of the scientists. I was known as a [National] Geographic cover girl,” she recalled in a CBS interview in 2012.

Her unorthodox personalizing of the chimps was particularly controversial. The editor of one of her first published papers insisted on crossing out all references to the creatures as “he” or “she” in favor of “it.” Goodall eventually prevailed.

Her most disturbing studies came in the mid-1970s, when she and her team of field workers began to record a series of savage attacks.

The incidents grew into what Goodall called the four-year war, a period of brutality carried out by a band of male chimpanzees from a region known as the Kasakela Valley. The marauders beat and slashed to death all the males in a neighboring colony and subjugated the breeding females, essentially annihilating an entire community.

It was the first time a scientist had witnessed organized aggression by one group of non-human primates against another. Goodall said this “nightmare time” forever changed her view of ape nature.

“During the first 10 years of the study I had believed … that the Gombe chimpanzees were, for the most part, rather nicer than human beings,” she wrote in “Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey,” a 1999 book co-authored with Phillip Berman. “Then suddenly we found that the chimpanzees could be brutal — that they, like us, had a dark side to their nature.”

Critics tried to dismiss the evidence as merely anecdotal. Others thought she was wrong to publicize the violence, fearing that irresponsible scientists would use the information to “prove” that the tendency to war is innate in humans, a legacy from their ape ancestors. Goodall persisted in talking about the attacks, maintaining that her purpose was not to support or debunk theories about human aggression but to “understand a little better” the nature of chimpanzee aggression.

“My question was: How far along our human path, which has led to hatred and evil and full-scale war, have chimpanzees traveled?”

Her observations of chimp violence marked a turning point for primate researchers, who had considered it taboo to talk about chimpanzee behavior in human terms. But by the 1980s, much chimp behavior was being interpreted in ways that would have been labeled anthropomorphism — ascribing human traits to non-human entities — decades earlier. Goodall, in removing the barriers, raised primatology to new heights, opening the way for research on subjects ranging from political coalitions among baboons to the use of deception by an array of primates.

Her concern about protecting chimpanzees in the wild and in captivity led her in 1977 to found the Jane Goodall Institute to advocate for great apes and support research and public education. She also established Roots and Shoots, a program aimed at youths in 130 countries, and TACARE, which involves African villagers in sustainable development.

She became an international ambassador for chimps and conservation in 1986 when she saw a film about the mistreatment of laboratory chimps. The secretly taped footage “was like looking into the Holocaust,” she told interviewer Cathleen Rountree in 1998. From that moment, she became a globe-trotting crusader for animal rights.

In the 2017 documentary “Jane,” the producer pored through 140 hours of footage of Goodall that had been hidden away in the National Geographic archives. The film won a Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. Award, one of many honors it received.

In a ranging 2009 interview with Times columnist Patt Morrison, Goodall mused on topics from traditional zoos — she said most captive environments should be abolished — to climate change, a battle she feared humankind was quickly losing, if not lost already. She also spoke about the power of what one human can accomplish.

“I always say, ‘If you would spend just a little bit of time learning about the consequences of the choices you make each day’ — what you buy, what you eat, what you wear, how you interact with people and animals — and start consciously making choices, that would be beneficial rather than harmful.”

As the years passed, Goodall continued to track Gombe’s chimps, accumulating enough information to draw the arcs of their lives — from birth through sometimes troubled adolescence, maturity, illness and finally death.

She wrote movingly about how she followed Mr. McGregor, an older, somewhat curmudgeonly chimp, through his agonizing death from polio, and how the orphan Gilka survived to lonely adulthood only to have her babies snatched from her by a pair of cannibalistic female chimps.

Jane Goodall in San Diego.

(Sam Hodgson / San Diego Union-Tribune)

Her reaction in 1972 to the death of Flo, a prolific female known as Gombe’s most devoted mother, suggested the depth of feeling that Goodall had for the animals. Knowing that Flo’s faithful son Flint was nearby and grieving, Goodall watched over the body all night to keep marauding bush pigs from violating her remains.

“People say to me, thank you for giving them characters and personalities,” Goodall once told CBS’s “60 Minutes.” “I said I didn’t give them anything. I merely translated them for people.”

Woo is a former Times staff writer.

Science

Mobile clinic brings mammograms to women on Skid Row

Sharon Horton stepped through the door of a sky-blue mobile clinic and onto a Skid Row sidewalk. She wore a yellow knit beanie, gold hoop earrings and the relieved grin of a woman who has finally checked a mammogram off her to-do list.

It had been years since her last breast cancer screening procedure. This one, which took place in City of Hope’s Cancer Prevention and Screening mobile clinic, was faster and easier. The staff was kind. The machine that X-rayed her breast was more comfortable than the cold hard contraption she remembered.

Relatively speaking, of course — it was still a mammogram.

“It’s like, OK, let me go already!” Horton, 68, said with a laugh.

The clinic was parked on South San Pedro Street in front of Union Rescue Mission, the nonprofit shelter where Horton resides. Within a week, City of Hope, a cancer research hospital, would share the results with Horton and Dr. Mary Marfisee, the mission’s family medical services director. If the mammogram detected anything of concern, they’d map out a treatment plan from there.

Naureen Sayani, 47, a resident of Union Rescue Mission, left, discusses her medical history with Adriana Galindo, a medical assistant, before getting a mammogram on last week.

(Kayla Bartkowski / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s very important to take care of your health, and you need to get involved in everything that you can to make your life a better life,” said Horton, who is looking forward to a forthcoming move into Section 8 housing.

Horton was one of the first patients of a new women’s health initiative from UCLA’s Homeless Healthcare Collaborative at Union Rescue Mission. Staffed by third-year UCLA Medical School students and led by Marfisee, a UCLA assistant clinical professor of family medicine, the clinic treats mission residents as well as unhoused people living in the surrounding neighborhood.

The new cancer screening project arrives at a time of dire financial pressures on county public health services.

Citing rising costs and a $50-million reduction in federal, state and local grant and contract income, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health on Feb. 27 ended services at seven of 13 public clinics that provide vaccines, tests and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases and other services to housed and unhoused county residents.

Although Union Rescue Mission’s own funding comes mainly from private sources and is less imperiled by public cuts, the 135-year-old shelter expects the need for its services to rise, Chief Executive Mark Hood said.

Even as unsheltered homelessness declined for the last two years across Los Angeles County, the unsheltered population on Skid Row — long seen as the epicenter of the region’s homelessness crisis — grew 9% in 2024, the most recent year for which census data are available.

For many local women navigating daily concerns over housing, food and personal safety, “their own health is not a priority,” Marfisee said.

Those whose problems have become too serious to ignore face daunting obstacles to care. Marfisee recalled one patient who came to her with a lump in her breast and no identification.

In order to get a mammogram, Marfisee explained, the woman first needed to obtain a birth certificate, and then a state-issued identification card. Then she needed to enroll in Medi-Cal. After that, clinic staff helped her find a primary care physician who could order the imaging test.

Given the barriers to preventative care, homeless women die from breast cancer at nearly twice the rate of securely housed women, a 2019 study found. Marfisee’s own survey of the mission’s female residents found that nearly 90% were not up to date on recommended cancer screenings like mammograms and pap smears, which detect early cervical cancer.

To address this gap, Marfisee — a dogged patient advocate — reached out to City of Hope. The Duarte-based research and treatment center unveiled in March 2024 its first mobile cancer screening clinic, a moving van-sized clinic on wheels that it deploys to food banks and health centers, as well as to companies offering free mammograms as an employee benefit.

“In true Dr. Mary fashion, she saw the vision,” said Jessica Thies, the mobile screening program’s regional nursing director. After working through some logistical hurdles, the mission and City of Hope secured a date for the van’s first visit.

The next challenge was getting the word out to patients. Marfisee and her students walked through the surrounding neighborhood, went cot to cot in the women’s dorm and held two informational sessions in December and January to answer patients’ questions.

At the sessions, the team walked through the basics of who should get a mammogram (women age 40 or older, those with a family history of breast cancer) and the procedure itself. (“Like a tortilla maker?” one woman asked skeptically after hearing a description of the mammography unit.)

The medical students were able to dispel rumors some women had heard: The test doesn’t damage breast tissue, nor do the X-rays increase cancer risk. Others questioned a mammogram’s value: What good was it knowing they had cancer if they couldn’t get follow-up care?

On this latter point, Marfisee is determined not to let patients fall through the cracks.

Thirteen patients received mammograms at the van’s first visit on Wednesday. Within a week, City of Hope will contact patients with their results and send them to Marfisee and her team. She is already mentally mapping the next steps should any patient have a situation that requires a biopsy or further imaging: working with their case manager at the mission, calling in favors, wrangling with any insurance the patient might have.

“It’ll be a good fight,” Marfisee said, as residents in the adjacent cafeteria carried trays of sloppy joes and burgers to their lunch tables. “But we’ll just keep asking for help and get it done.”

Science

Can fire-resistant homes be sexy? ‘You be the judge,’ says this Palisades architect

At first glance, it looks like nothing more than a charming Spanish-revival, quintessentially Californian home — but this Pacific Palisades rebuild is constructed like a tank.

Every exterior wall of the steel-framed home is a foot-thick, fire-resistant barricade. The home is connected to a satellite fire monitoring service. Should a fire start in town, sturdy metal shutters descend to cover every window. An exterior sprinkler system can pump 40,000 gallons of water from giant tanks hidden behind the shrubs in the property’s yard. If the cameras and heat sensors around the house detect danger, the system can envelop the home in over 1,000 gallons of fire retardant and hundreds of gallons of fire-suppressing foam.

Palisades resident and architect Ardie Tavangarian is so confident in his design that he even asked the fire department if they could start a controlled fire on the property to test it all out. (They said no.)

Tavangarian built a career designing multimillion-dollar luxury homes in Los Angeles, but after the Palisades fire destroyed 13 of his works — including his family’s home — he found another calling: how to design a house that can handle what the Santa Monica Mountains throw at it. And how to do it quickly and affordably.

Water tanks form part of a backup water supply in a newly built fire-resistant home in Pacific Palisades.

“Nature is so powerful,” he said, sitting on a couch in the new house, which he built for his adult twin daughters. “We are guests living in that environment and expecting, ‘Oh, nature is going to be really kind to me.’ No, it’s not. It does what it’s supposed to do.”

Tavangarian watched the Jan. 1 Lachman fire from his property not far from here; a week later that fire rekindled, grew into the Palisades fire, and burned through his house. But the painful details of the fire — the missteps of the fire department, the empty reservoir — didn’t matter when it came to deciding how to rebuild, he said. The reality is, many fires have burned in these mountains. Many more will.

A sprinkler on the roof is part of a house-wide sprinkler system.

For the architect, who has spent much of his 45-year career designing for luxury, hardening a home against wildfire has brought a new kind of luxury to his homes: peace of mind.

It’s a sentiment that resonates with fire survivors: Tavangarian says he’s received considerable interest from other property owners in the Palisades looking to rebuild their houses.

The metal shutters and advanced outdoor sprinkler system are the flashiest parts of Tavangarian’s home hardening project, and the efficacy of these adaptations is still up for debate. Because the measures have not yet been widely adopted, there are few studies exploring how much or little they protect homes in real-world fires.

Architect Ardie Tavangarian inside the house he designed.

Anecdotal evidence has indicated the effectiveness of sprinklers can vary significantly based on the setup and the conditions during the fire. Extreme wind, for example, can make them less effective. Lab studies have generally found shutters can reduce the risk of windows shattering.

These measures aren’t cheap, either. Sprinkler systems can cost north of $100,000, for example. However, Tavangarian said when all was said and done, the home he built for his daughters cost around $700 per square foot — less than what Palisades residents said they expected to pay, but more than what Altadena residents expected for their rebuilds.

Tavangarian also hopes to see insurers increasingly consider the home-hardening measures property owners take when writing policies, which he said could potentially offset the extra cost in a decade or less. As he explored getting insurance for the new home, one insurer quoted him $80,000 a year. After he convinced the company to visit the property, it lowered the quote to just $13,000, he said.

The house includes metal heat shields that can drop down if a fire approaches.

The home also has essentially all of the other less flashy — but much cheaper and well-proven — home hardening measures recommended by fire professionals: The underside of the roof’s overhang is closed off — a common place embers enter a home. The roof, where burning embers can accumulate, is made of fire-resistant material. The windows, vulnerable to shattering in extreme heat, are made of a toughened glass. There is virtually no vegetation within the first five feet of the home.

When asked if he felt he had compromised on design, comfort or aesthetics for the extra protection — one of the many concerns Californians have with the state’s draft “Zone Zero” requirements that may significantly limit vegetation within five feet of a home — Tavangarian simply said, “You be the judge.”

Science

Commentary: My toothache led to a painful discovery: The dental care system is full of cavities as you age

I had a nagging toothache recently, and it led to an even more painful revelation.

If you X-rayed the state of oral health care in the United States, particularly for people 65 and older, the picture would be full of cavities.

“It’s probably worse than you can even imagine,” said Elizabeth Mertz, a UC San Francisco professor and Healthforce Center researcher who studies barriers to dental care for seniors.

Mertz once referred to the snaggletoothed, gap-filled oral health care system — which isn’t really a system at all — as “a mess.”

But let me get back to my toothache, while I reach for some painkiller. It had been bothering me for a couple of weeks, so I went to see my dentist, hoping for the best and preparing for the worst, having had two extractions in less than two years.

Let’s make it a trifecta.

My dentist said a molar needed to be yanked because of a cellular breakdown called resorption, and a periodontist in his office recommended a bone graft and probably an implant. The whole process would take several months and cost roughly the price of a swell vacation.

I’m lucky to have a great dentist and dental coverage through my employer, but as anyone with a private plan knows, dental insurance can barely be called insurance. It’s fine for cleanings and basic preventive routines. But for more complicated and expensive procedures — which multiply as you age — you can be on the hook for half the cost, if you’re covered at all, with annual payout caps in the $1,500 range.

“The No. 1 reason for delayed dental care,” said Mertz, “is out-of-pocket costs.”

So I wondered if cost-wise, it would be better to dump my medical and dental coverage and switch to a Medicare plan that costs extra — Medicare Advantage — but includes dental care options. Almost in unison, my two dentists advised against that because Medicare supplemental plans can be so limited.

Sorting it all out can be confusing and time-consuming, and nobody warns you in advance that aging itself is a job, the benefits are lousy, and the specialty care you’ll need most — dental, vision, hearing and long-term care — are not covered in the basic package. It’s as if Medicare was designed by pranksters, and we’re paying the price now as the percentage of the 65-and-up population explodes.

So what are people supposed to do as they get older and their teeth get looser?

A retired friend told me that she and her husband don’t have dental insurance because it costs too much and covers too little, and it turns out they’re not alone. By some estimates, half of U.S. residents 65 and older have no dental insurance.

That’s actually not a bad option, said Mertz, given the cost of insurance premiums and co-pays, along with the caps. And even if you’ve got insurance, a lot of dentists don’t accept it because the reimbursements have stagnated as their costs have spiked.

But without insurance, a lot of people simply don’t go to the dentist until they have to, and that can be dangerous.

“Dental problems are very clearly associated with diabetes,” as well as heart problems and other health issues, said Paul Glassman, associate dean of the California Northstate University dentistry school.

There is one other option, and Mertz referred to it as dental tourism, saying that Mexico and Costa Rica are popular destinations for U.S. residents.

“You can get a week’s vacation and dental work and still come out ahead of what you’d be paying in the U.S.,” she said.

Tijuana dentist Dr. Oscar Ceballos told me that roughly 80% of his patients are from north of the border, and come from as far away as Florida, Wisconsin and Alaska. He has patients in their 80s and 90s who have been returning for years because in the U.S. their insurance was expensive, the coverage was limited and out-of-pocket expenses were unaffordable.

“For example, a dental implant in California is around $3,000-$5,000,” Ceballos said. At his office, depending on the specifics, the same service “is like $1,500 to $2,500.” The cost is lower because personnel, office rent and other overhead costs are cheaper than in the U.S., Ceballos said.

As we spoke by phone, Ceballos peeked into his waiting room and said three patients were from the U.S. He handed his cellphone to one of them, San Diegan John Lane, who said he’s been going south of the border for nine years.

“The primary reason is the quality of the care,” said Lane, who told me he refers to himself as 39, “with almost 40 years of additional” time on the clock.

Ceballos is “conscientious and he has facilities that are as clean and sterile and as medically up to date as anything you’d find in the U.S.,” said Lane, who had driven his wife down from San Diego for a new crown.

“The cost is 50% less than what it would be in the U.S.,” said Lane, and sometimes the savings is even greater than that.

Come this summer, Lane may be seeing even more Californians in Ceballos’ waiting room.

“Proposed funding cuts to the Medi-Cal Dental program would have devastating impacts on our state’s most vulnerable residents,” said dentist Robert Hanlon, president of the California Dental Assn.

Dental student Somkene Okwuego smiles after completing her work on patient Jimmy Stewart, 83, who receives affordable dental work at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC on the USC campus in Los Angeles on February 26, 2026.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Under Proposition 56’s tobacco tax in 2016, supplemental reimbursements to dentists have been in place, but those increases could be wiped out under a budget-cutting proposal. Only about 40% of the state’s dentists accept Medi-Cal payments as it is, and Hanlon told me a CDA survey indicates that half would stop accepting Medi-Cal patients and many others will accept fewer patients.

“It’s appalling that when the cost of providing healthcare is at an all-time high, the state is considering cutting program funding back to 1990s levels,” Hanlon said. “These cuts … will force patients to forgo or delay basic dental care, driving completely preventable emergencies into already overcrowded emergency departments.”

Somkene Okwuego, who as a child in South L.A. was occasionally a patient at USC’s Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry clinic, will graduate from the school in just a few months.

I first wrote about Okwuego three years ago, after she got an undergrad degree in gerontology, and she told me a few days ago that many of her dental patients are elderly and have Medi-Cal or no insurance at all. She has also worked at a Skid Row dental clinic, and plans after graduation to work at a clinic where dental care is free or discounted.

Okwuego said “fixing the smiles” of her patients is a privilege and boosts their self-image, which can help “when they’re trying to get jobs.” When I dropped by to see her Thursday, she was with 83-year-old patient Jimmy Stewart.

Stewart, an Army veteran, told me he had trouble getting dental care at the VA and had gone years without seeing a dentist before a friend recommended the Ostrow clinic. He said he’s had extractions and top-quality restorative care at USC, with the work covered by his Medi-Cal insurance.

I told Stewart there could be some Medi-Cal cuts in the works this summer.

“I’d be screwed,” he said.

Him and a lot of other people.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO6 days ago

Denver, CO6 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Florida2 days ago

Florida2 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoArturia’s FX Collection 6 adds two new effects and a $99 intro version

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: How Lunar New Year Traditions Take Root Across America