News

Can indigenous knowledge help us design a more sustainable future?

On the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Iraq, a neighborhood referred to as the Ma’dan, or Marsh Arabs, reside in floating thatched villages as soon as so quite a few they have been dubbed the Mesopotamian Venice. Their properties — hand sculpted from qasab reeds — bear little resemblance to their Italian counterparts, however might they maintain classes for a way we construct extra ecologically sound Venices sooner or later?

Most of the Ma’dan have been compelled on to dry land in latest a long time resulting from droughts and deliberate drainage of the wetlands for political ends. However whereas their lifestyle is likely to be beneath menace, their ingenuity is lastly being recognised: with the elevated threat of flooding resulting from local weather change, the necessity for man-made islands is changing into a looming prospect — and designers and designers are on the lookout for options.

“The Ma’dan tradition affords a residing instance of how future water-based civilisations can reside sustainably and symbiotically,” says designer Julia Watson, who’s collaborating with the neighborhood on an set up for the Barbican’s exhibition Our Time on Earth, opening in London in Could. It’s certainly one of a collection of spring reveals taking a look at how conventional ecological data can nurture the well being of the planet, together with Gaining Floor at London’s Craft Council Gallery and the Bio27 design biennial in Ljubljana.

Watson factors to how the Ma’dan construct their islands atop fenced-off sections of residing reeds, which filter pollution from the water, defending its wealthy ecosystem. “Biodiversity is a constructing block on which these cultures float,” is how she described it in her 2019 ebook LoTek: Design by Radical Indigenism. They make all the pieces, from the islands themselves to homes and furnishings, from one pure materials, utilizing strategies honed over 5,000 years.

Whereas individuals within the west are unlikely to decamp to floating reed properties, the thought of working with nature, not in opposition to it, is gaining traction.

Our Time on Earth entails designers, scientists and artists and affords, the Barbican says, “visions and prospects for the way forward for all species”. Watson is working with the Ma’dan neighborhood, the Khasis hill tribe of north-eastern India — well-known for its residing bridges constituted of aerial roots of rubber fig bushes — and farmers in Bali recognized for his or her Subak water irrigation system that creates fertile rice terraces and bolsters the native ecosystem.

Multimedia set up “The Symbiocene”, made in collaboration with architect Smith Mordak of Buro Happold, will think about how city environments would possibly look in 2040 if we incorporate indigenous applied sciences.

The Barbican’s present comes at a second of reckoning for designers and designers. Lately, the main focus has been on utilizing pure assets higher and lowering emissions — pressing priorities when buildings and building create practically 40 per cent of world emissions, in keeping with the World Inexperienced Constructing Council. However, with biodiversity declining sooner than ever, the necessity for design to drive regeneration is crucial. Since 1970, we’ve got misplaced 68 per cent of mammal, chook, amphibian, reptile and fish populations, says the World Wildlife Fund’s Dwelling Planet Report 2020.

Indigenous peoples presently take care of about 80 per cent of world biodiversity, however are disproportionately affected by local weather change and extractive agriculture practices, pushed by the world’s starvation for supplies. A brand new UN Surroundings Programme report predicts will increase in wildfires, if greenhouse emissions proceed at their present charge, within the forests of Indonesia and the Amazon, which suffered report deforestation for the month of January.

The properties of the Ma’dan themselves have been largely destroyed by the drainage of the Mesopotamian marshlands that started within the Fifties for oil exploration and agriculture and continued within the Nineteen Nineties when Saddam Hussein focused the Ma’dan as political opponents. Within the aftermath of a Shia rebellion in opposition to his Ba’ath social gathering, he turned the world — the place lots of the rebels had retreated — right into a desert as a punishment.

Since 2003, it has been partially reflooded and restored and a number of the Ma’dan have rebuilt their properties, although the development of dams upriver and a collection of droughts imply their future on the water is fragile, as is the biodiversity of the wetlands.

However, a shift to extra planet-positive practices is starting within the design world. Final month the British Council introduced the 2023 British Pavilion on the Venice Structure Biennale will discover “non-extractive” design, taking a look at how diasporic craft cultures may be a part of an structure “constructed on rules of care and fairness over extraction and exploitation”.

In the meantime, 1,212 UK structure companies have signed as much as an initiative referred to as Architects Declare, pledging to design buildings with a constructive environmental influence. “We have to overcome the separation between man and nature that encourages extraction,” says co-founder Michael Pawlyn, founding father of Exploration Structure and an professional in biomimetic design, which imitates pure methods. His new ebook Flourish, co-written by Sarah Ichioka, is a name to arms for designers to seek out new types of artistic coexistence, “a lot as many Indigenous cultures have accomplished for millennia”.

Whereas it could be mistaken to say no indigenous neighborhood has ever overstepped nature’s boundaries, interdependence is embedded in some communities’ non secular beliefs. “We’re part of the land and nature, and our creation tales give attention to this,” says environmental scientist Jessica Hernandez of her Maya Ch’orti’ and Zapotec kin. “Because of this, we don’t ‘personal’ the land, however somewhat coexist with it as kinfolk.”

In her new ebook Contemporary Banana Leaves, she argues that western notions of conservation and creating nationwide parks have strengthened the separation between people and nature, whereas displacing indigenous peoples.

In the meantime, botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, requires a mutual flourishing between each in her best-selling ebook Braiding Sweetgrass, describing vegetation as items. “Turning into indigenous to a spot means residing as in case your youngsters’s future mattered, to care for the land as if our lives, each materials and non secular, trusted it,” she writes.

In her tales of indigenous knowledge, she recounts how black ash bushes, a declining species in Oklahoma, thrive the place Potawatomi basket makers harvest their supplies, creating areas within the forest cover for brand spanking new progress.

To stimulate such reciprocity at house, the primary query a designer ought to ask is “what supplies and options exist already in a spot?” says Pawlyn. “What’s particular in regards to the Ma’dan is how they’ve created a whole architectural language out of an plentiful native materials.”

He finds comparative promise in a brand new piece of British design ingenuity, Flat Home, a zero-carbon house in Cambridgeshire created for movie director Steve Barron by Follow Structure. It’s constituted of prefabricated panels of hemp — a fast-growing, insulating fibre that sequesters extra carbon than typical forestry, say the architects — cultivated on the encompassing farm. “Flat Home has a web constructive impact, somewhat than simply mitigating the detrimental influence of building.”

This intertwining of farming and making is seen in lots of rural communities worldwide, making certain extra balanced consumption. Within the Selaawi village, situated in Indonesia’s West Java Province, for instance, the identical individuals who harvest bamboo additionally weave it into baskets. They choose solely mature shoots as a result of they imagine slicing the youthful ones would have an effect on the entire household.

However as demand for this renewable materials prompts industrial farming, such ecological knowledge is being ignored. “It has affected the bamboo forests, and the varieties are lowering,” says an area artisan, Utang Mamad.

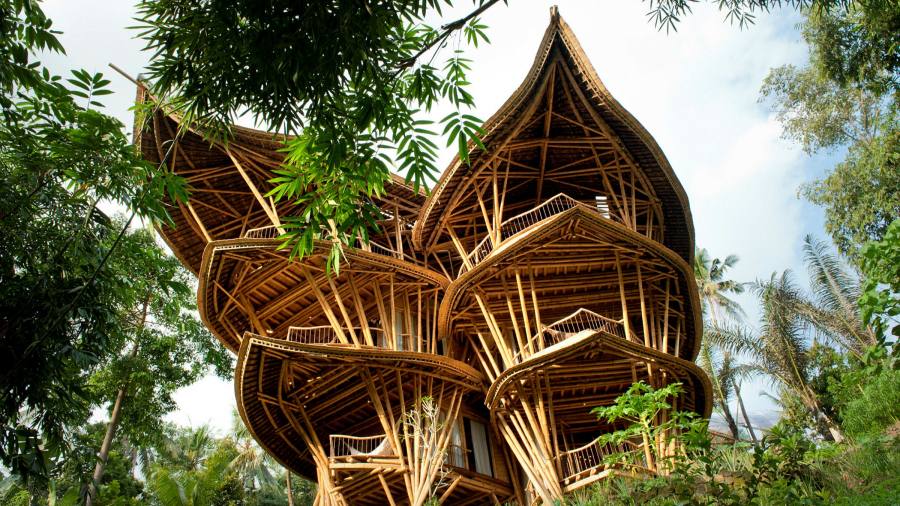

This data is heeded by Bali-based structure follow Ibuku, which builds bamboo properties that mix with their environments. Ibuku’s craftspeople solely use mature bamboo poles from Bali and Java “to create an incentive for the bamboo farmers to permit the youthful shoots to develop to maturity”. Right here, the intertwining of design and conventional ecological data (TEK) helps shift behaviour.

The Selaawi artisans are a part of “Making Nature”, a British Council-funded digital map of craft practices in Indonesia and the UK that profit native ecologies. It is going to be proven within the Crafts Council Gallery’s April exhibition Gaining Floor, exploring international craft practices in sync with nature.

The map reveals how British designers are re-engaging with vernacular practices to regenerate the land. In Cumbria, swill basket-maker Lorna Singleton coppices her oak from surrounding woodlands — a centuries-old follow that encourages progress and permits gentle into the forest flooring, boosting biodiversity. “It mimics the trampling impact that mammoths as soon as created,” she says.

In Kent, furnishings maker Sebastian Cox coppices 4 acres of historical woodland, seeing the timber as a byproduct of conservation. “Our furnishings tells the story of what accountable forestry might appear like,” he says.

Such concepts recall the land stewardry practices typically utilized by indigenous communities to stimulate progress. However because the artistic world wakes as much as the significance of inherited ecological knowledge and design applied sciences, how can we guarantee these most in danger from local weather change aren’t now exploited for his or her data?

“We have to keep away from a scenario the place we’re merely extracting their applied sciences from them,” says Julia Watson. To safeguard the mental property of the communities, the Barbican collaborators will take an oral “Oath of Understanding”, to be entered into via unalterable “sensible contracts” encoded on public blockchains.

It’s a fancy subject, says Jay Mistry, a ceramic artist and professor of environpsychological geography at Royal Holloway, College of London. “A key problem is illustration.” She is engaged on a Darwin Initiative-backed mission to combine conventional data into national coverage in Guyana. “I’m taking a look at how the methods indigenous peoples handle the surroundings may be introduced into the mainstream however, importantly, we’re making an attempt to make sure they’re a part of decision-making in order that they profit from it.”

Mistry is rejuvenating a number of the cultural and ecological data that disappeared throughout colonial occasions, specifically the pottery practices of Macushi and Wapishana. The outcomes — made utilizing wild clays fired at low temperatures in order that they’ll biodegrade — have impressed Mistry’s personal ceramics, which will likely be proven in Gaining Floor.

Globalisation has had related results in Mexico. Right here designer Fernando Laposse is making an attempt to reinstate native agricultural practices and enhance livelihoods. He creates sisal furnishings — bushy, characterful items that call to mind Cousin Itt — bought internationally, reminiscent of at London’s Sarah Myerscough Gallery. However these works are simply an offshoot of his conservation efforts within the area surrounding the village of Tonahuixtla.

“My design items are the final step in a collection of actions to cease land erosion,” he says. With native farmers, he’s reversing the injury attributable to chemical-heavy industrial farming — launched after the North American Free Commerce Settlement in 1994 — that turned fertile lands into deserts. They’ve planted agaves over 120 hectares utilizing a historic terracing system to create water and soil retention. Now life is returning and native individuals are employed to show the sisal fibres from the agaves into furnishings. “We’ve created a brand new craft that funds environmental restore.”

It’s an concept that curator Jane Withers calls “tremendous vernaculars” in her theme for Ljubljana’s Bio27 design biennial from Could, displaying Laposse’s enterprise, amongst others. “Removed from being nostalgic, it’s about recognising the worth of TEK as a catalyst for uplifting up to date design tradition in tune with nature in order that we are able to dismantle the poisonous values attributable to international growth and the pursuit of revenue first,” she says.

Withers is assembling teams of designers, ecologists and materials scientists to provide you with options for native Slovenian wants that draw on native and worldwide data. “Design has been in a silo for too lengthy,” she says.

Such pondering might permeate the realm of luxurious items too, with the LVMH group teaming up with London’s Central Saint Martins artwork faculty to launch a Regenerative Design MA in September. “It is going to be taught on-line so that individuals can establish issues of their native ecosystems and communities, then reply,” says Professor Carole Collet — concepts, one hopes, that can feed into LVMH manufacturers, which embrace Louis Vuitton and Dior.

However design schooling, concept sharing and collective motion are simply a part of the systemic change wanted to quell our extractive behaviour en masse. “If our financial fashions proceed to reward limitless progress, each species will likely be in hassle,” says Pawlyn. Boosting biodiversity is one thing through which we should always all be invested.

“Our Time on Earth” is on the Barbican, London, Could 5- August 29; barbican.org.uk

Comply with @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to seek out out about our newest tales first