Lifestyle

Weed changed this California town. Now artsy residents are all in on psychedelics

On a brisk mid-March night in the small Northern California town of Grass Valley, more than 100 people crowded around a Grateful Dead cover band in a drafty warehouse. They were an eccentric mix: aging hippies, hypebeast college kids and burners bundled in faux fur rainbow coats, swaying to guitar riffs. In the parking lot, people exchanged cigarettes, joints, pills and powders.

Scenes from a night at the Chambers Project, an art gallery curated by Brian Chambers in Grass Valley, California.

(Colin M. Day)

This is a typical night at the warehouse — home to an art gallery called the Chambers Project and a new nonprofit, Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT). It sits just off State Route 49 and shares its parking lot with a natural foods store. From the road, it can be identified only from its logo: an illuminati eye nestled into a pyramid, which sheds a tear into a river that vanishes into the horizon. The image was drawn by one of the most famous psychedelic artists, Rick Griffin, who created seven album covers for the Grateful Dead.

The logo was a taste of what awaited inside. Almost every corner of the warehouse was covered in trippy art. From the ceiling hung a twisted glass chandelier by Eric Dunn, its spiked lampshades mimicking the tendrils of a brain’s dendrites. On the walls were dozens of otherworldly paintings by Mario Martinez (a.k.a. MARS-1), who renders amorphous architecture straight out of science fiction. Behind the musicians, sculptures of bright pink disembodied legs and a matching pink unicorn in medieval armor add trippy ambience. Outside, projected onto the facade, was a kaleidoscopic video that overlaid cartoonish eyes, lightning bolts and sacred geometry.

Brian Chambers, founder and curator of the gallery, is the face of this event. The concert was part of the opening reception for his gallery’s new exhibition, “The Godfathers” — which showcases four artists who defined the art movement — and also the launch party for PACT, which he hopes will be a a community hub for the psychedelic-curious, whether that pertains to art, experimenting with substances, or educational programming about the two.

A recent PACT event included a benefit concert to raise money for a local marijuana farmer known as Uncle Jay, who’s battling cancer. This month, an exhibition of peyote paintings will donate proceeds to the Wixárika tribe of northwestern Mexico, California, Arizona and Texas — Indigenous people whose shamans famously guide people through spiritual peyote ceremonies.

They are also planning talks about major moments within psychedelic art history, a deep dive of blotter art, and a panel on magic mushrooms and their scientific properties.

“We have a community of care,” said Marci Hovanski, 48, who works at the natural foods store next door. “Brian’s bringing something so special, and it really just raises the whole frequency of the neighborhood.”

Mary Barry, 74, and her husband Jesus Ceballos, 72, have been attending Chambers’ art openings for years. Like many residents in Nevada County, where the biggest cash crop is marijuana, they moved to the quiet town 51 years ago to work on a friend’s weed farm and never left.

Ceballos wears a tangle of walrus beads over his tie-dye Grateful Dead T-shirt. He and Barry came tonight because they wanted to see the artwork and hear the Grateful Dead cover band. They’ve seen the original group play at least 50 shows, often timing the moment they dropped acid so they peaked at the song “Greensleeves.”

“If you’ve ever done psychedelics you feel comfortable in this environment. People recognize each other and they feel safe.”

— Marci Hovanski, Chambers Project patron

Grateful Dead shows were places for them to experiment with drugs, and Ceballos compares the Chambers Project to that environment. “The vibe here is very, very good,” he said.

In this way, Chambers’ nonprofit functions as a third space for the local community, especially those who dabble in psychedelics — substances like psilocybin (magic mushrooms), peyote, ayahuasca, DMT, LSD, ketamine and MDMA — that affect the mind and often cause hallucinations. Whether someone’s smoking weed to make art-viewing more pleasurable, dropping acid to enhance a concert experience, or dosing magic mushrooms to go on a path of self-discovery, Hovanski said the Chambers Project provides a nonjudgmental setting to do that.

“If you’ve ever done psychedelics, you feel comfortable in this environment,” Hovanski said. “People recognize each other and they feel safe.”

Even so, she said visiting the gallery is thrilling while sober too. “People can just go there and be themselves. It’s kind of magic. … It’s opened up a space that holds the rainbow. It’s like the end of the rainbow.”

The Chambers Project warehouse sits just off State Route 49 and is home to an art gallery and a new nonprofit, Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT).

(Colin M. Day)

Life after weed farms

After California legalized recreational marijuana in 2016, Grass Valley’s economy entered a recession. Many independent farmers couldn’t meet the regulation requirements for legal operation and shut down. Psychedelic culture, however, might be the ticket to Grass Valley’s recovery; through Chambers’ magnetism, more artists have been taking trips to this rural town on the Yuba River.

“Tourism is like the only thing we’ve got going,” Hovanski said. “Brian opened a light, a place for people to see love or care. That just opens the space for more creativity, more greatness.”

Before trekking to Grass Valley, I first met Chambers over Zoom in February. The 44-year-old gallerist has a long, gray beard. The day we spoke he wore a baseball cap embroidered with the illuminati eye from the Chambers Project logo. In the background was a large, red swirling canvas by MARS-1, a young artist whom Chambers has mentored. Positioned behind Chambers, it made him glow like a martian.

“This is a moment that I’ve been anticipating and waiting for,” he said.

He was referring to a cultural shift surrounding psychedelics. Many cities across the nation have decriminalized possession and in Oregon and Colorado, voters passed ballots that allowed for state-regulated psilocybin medical centers. Oregon opened its first psilocybin clinic in 2023, and so-called healing centers are slated to arrive in Colorado in 2025.

“This is a moment that I’ve been anticipating and waiting for.”

— Brian Chambers, founder of the Chambers Project and the nonprofit Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT)

In the meantime, cities are advocating for psychedelics use on the local level. In the last five years, possession of magic mushrooms has been decriminalized to varying degrees in cities across California, including Oakland, Santa Cruz, Arcata, San Francisco, Berkeley and Eureka.

Last October, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a state-wide bill that would have decriminalized various psychedelics. Legislators, in step with public opinion, have nevertheless continued their push to grant wider access to the substances. State Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) introduced a plan in February that would legalize psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Beyond the medical industry, psychedelic aesthetics are jumping from counterculture into the mainstream: There are now black light-lit bars that specialize in kava, a root plant that can produce low-level psychoactive effects; immersive art chains like Meow Wolf, which sells chromadepth glasses that mimic a trip by producing prismatic halos around lights; and even a brand new shroom festival in Denver, which will have mushroom grow kits for sale.

Artwork featured at the Chambers Project’s “Godfathers” exhibition.

(Colin M. Day)

A looming shift

Due to recent studies, including an FDA-backed statement that “psychedelic drugs show initial promise as potential treatments for mood, anxiety and substance use disorders,” the substances may be on the precipice of legalization in California and across the United States.

“Psychedelics are remarkable for their potential to elicit non-ordinary states of consciousness and ability to facilitate healing through experiences of profound transpersonal and mystical states,” said Barbara Chandler, a therapist and ketamine-assisted psychotherapist based in Truckee.

“These experiences can expand one’s sense of self and deepen one’s understanding of existence and connectedness,” she said.

Chambers sees the timing of PACT’s launch as a chance to take advantage of this shift. He wants the organization to be a resource for the new generation of people discovering these substances.

“People that are exploring it and getting into that side of life are doing it with an intention,” Chambers said. “They’re trying to use them as tools to get through it. I see enormous value in that, and I think it’s a beautiful thing.”

Chambers is alluding to the fact that recent research has shown that psychedelic-assisted therapy — when drugs are combined with psychotherapy or talk-therapy — can treat PTSD, depression and chronic pain. It’s possible this has helped destigmatize the drugs. A recent poll out of UC Berkeley shows that 61% of registered voters across America support regulated use of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Currently the federal government classifies all psychedelics as Schedule I controlled substances, meaning they have “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” But there are signs the FDA is getting closer to downgrading that status for psilocybin, LSD and MDMA. Compass Pathways and the Multidisciplinary Assn. for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) are among organizations that have entered phase III clinical trials with psilocybin and MDMA therapies. Experts say that’s the final hoop to clear before federal agencies acknowledge a drug’s medical potential and clear it for FDA-approved programs.

In June 2023, the FDA issued its first draft guidance for conducting psychedelic research. That will help scientists design studies that can lead to the drugs being approved for the market.

“The move by the FDA has researchers, advocates for veterans and others hopeful for the development of better medication for frequently diagnosed disorders,” Eric Licas reported for The Times in 2023.

Medical providers have already used legal loopholes to get certain illegal substances to patients. Ketamine, for example, is FDA-approved for anesthetic use, which allows clinics to obtain it. They can then turn around and administer it off-label, meaning they can use it for an unapproved treatment, which is legal so long as “it is based in sound medical evidence.” This workaround has helped roughly 500 to 750 ketamine clinics pop up around the country since 2020.

Artwork featured at the Chambers Project’s “Godfathers” exhibition.

(Colin M. Day)

Reaching a new generation

As a longtime user of psychedelic substances, Chambers sees legalization as the new gateway into his culture. He discovered psychedelic drugs in 1995 during his sophomore year of high school, when he said he showed up to his science class on LSD and became enthralled with an Alex Grey poster that hung in the classroom.

Beyond its mental effects, he was immediately drawn to the aesthetics — swirling colors, optical illusions and surreal depictions of cognition — associated with it. At age 15, he purchased his first piece of art, a “Bicycle Day” poster celebrating the discovery of LSD signed by the chemist who made it. Chambers, who said he earned a comfortable living in the marijuana industry, owns roughly 400 works of psychedelic art.

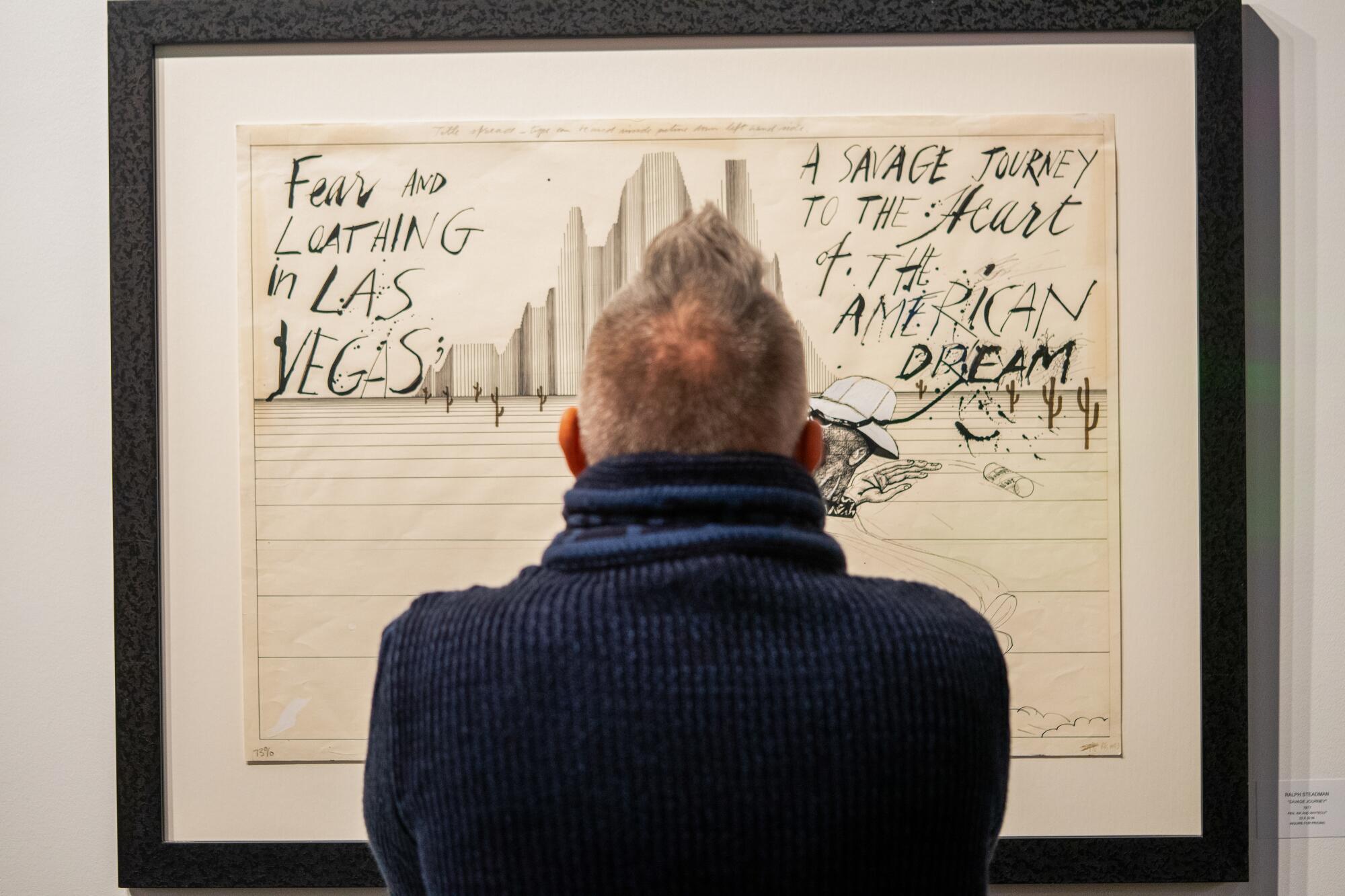

That candy-colored trove now rotates through the Chambers Project. The current “Godfathers” show (running until May 25) includes original pen-and-ink drawings that Ralph Steadman drew for Hunter S. Thompson’s seminal work of gonzo journalism, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”; Rick Griffin’s “flying eyeball,” which cemented itself into history when it appeared on a Jimi Hendrix Experience concert poster in 1968; the pop surrealist Roger Dean’s “Relayer,” a serpentine painting that became an album cover for the prog-rock band Yes; and ephemera from a gritty Manhattan venue called Psychic Solutions Gallery, founded by Jacaeber Kastor, that treated blotter papers as high art.

Brian Chambers, left; Jacaeber Kastor, right. Kastor is one of the artists in the exhibition and founded Psychedelic Solution Gallery, a gritty Manhattan venue that treated blotter papers as high art.

(Colin M. Day)

Since psychedelics have become less taboo, the interest in Chambers’ art collection has grown. He said he has sold work to the Pritzker family, which has placed a number of his pieces at its Grand Hyatt Hotel in San Francisco. Often deemed lowbrow, unserious and too commercial, a wider acceptance of magic mushrooms and ketamine among some pockets of the country also means that the art is no longer reserved for outcasts and hippies.

“We’re trying to make these world-class, globally known artists accessible to the common folk that don’t come from money or a serious art background,” Chambers said.

He supports artists like MARS-1, Damon Soule and Justin Lovato by providing them studio space, showing their work and selling it to his network of collectors. Chambers has also encouraged many of these artists to relocate to Grass Valley to be closer to the community he’s building.

Chambers met Soule, a 49-year-old artist known for drawing flowing grids as optical illusions, in 2009 in San Francisco. Five years later he made the move to the woods. Soule chatted with me over Zoom from his homemade art studio in April, where he relied on one bar of spotty cell service. Pixelated, he sat in front of plywood walls covered with black-and-white painting studies, an artsy recluse in his off-grid sanctuary.

“Artists tend to be individualistic and focused on their own little world,” he said. “Brian is a connection-maker. It’s good to be near someone who helps you meet other artists, other musicians, people who have parties and collaborative events.”

Scenes from a night at the Chambers Project, an art gallery curated by Brian Chambers.

(Bailey Whitehill)

Soule calls PACT “the clubhouse” because it’s always filled with a diverse set of creative people united by the profound experiences they had taking psychedelics.

When I spoke to Chambers, he was careful to clarify that, though he is a passionate advocate of psychedelics, PACT is not a medical organization, nor does it distribute substances. Instead, they focus on education by holding discussions with experts, historians and artists who help people understand how to safely consume drugs if they so desire.

Gagan Levy, a PACT board member and founder of We Are Guru, a creative agency that plays a large role in pushing for the legalization of psilocybin, believes PACT’s discussions are crucial for building a positive relationship with the drugs. He emphasizes the importance of “set and setting.” The phrase was coined by his mentor Ram Dass, the famed Harvard scientist and spiritual icon who conducted groundbreaking studies on psychedelics in the 1960s and wrote “Be Here Now.”

“We don’t have a Hunter S. Thompson, or ‘Fear and Loathing’ like that. We’re trying to recapture that, but in a totally new and weird way.”

— Woody Tuttle, Chambers Project patron

“What’s your mindset and the setting going into a psychedelic experience?” he asked. “Then, how do you have a mind-expanding experience, but, most importantly, how do you then integrate that into your life to be more fulfilled?”

Woody Tuttle, 21, traveled from Chico to attend the “Godfathers” opening. He said that because his generation lacks a true counterculture movement, his cohort sees psychedelics as more spiritual gateways to connecting with art, nature and other people. He said many of his peers are pairing their experiences with chants, intention-setting, spells and manifestation.

“We don’t have a Hunter S. Thompson, or ‘Fear and Loathing’ like that,” Tuttle said. “We’re trying to recapture that, but in a totally new and weird way.”

A Chambers Project visitor views artwork by “Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas” artist Ralph Steadman.

(Colin M. Day)

PACT cultivates an environment where people can discuss how psychedelics have provided them breakthroughs, healing and answers to personal questions.

“Integrating the psychedelic experience is as important as the experience itself,” the artist Soule said. “For me, art is the most direct way of transmuting all types of metaphysical spaces into the default world. It resonates with people by giving them a reflection of those shared places, states, mysteries.”

In Grass Valley, the community has embraced PACT and the Chambers Project. Their parties regularly sell out, the gallery has made the front page of the local newspaper more than once, and the Nevada County Arts Council has arranged private gallery tours for visitors.

By fostering a community around art, music and education, PACT hopes to transform this small, rural town into a preeminent hub for psychedelic culture.

“The art speaks for itself and it has really inspired a movement,” Chambers said.

Renée Reizman is an interdisciplinary writer, artist and educator based in Los Angeles. She researches the ways infrastructure impacts culture, community and environment. Find her work at @reneereizman.

Lifestyle

For filmmaker Chloé Zhao, creative life was never linear

In 2021, Zhao made history as the first woman of color to win the best director Oscar for her film Nomadland. Her Oscar-nominated drama Hamnet has made $70 million worldwide.

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

It took a very special kind of spirit to make Hamnet, which is nominated for best picture at this year’s Academy Awards. Chloé Zhao brought her uniquely sensitive, mind-body approach to directing the fictionalized story about how William Shakespeare was inspired to write his masterpiece Hamlet.

Zhao adapted the screenplay from a novel by Maggie O’Farrell, and for directing the film, she’s now nominated for an Oscar. She could make history by becoming the first woman to win the best director award more than once.

Zhao says she believes in ceremonies and rituals, in setting an intention, a mood, a vibration for any event. Before Hamnet premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, she led the audience in a guided meditation and a breathing exercise.

Zhao also likes to loosen up, like she did at a screening of Hamnet in Los Angeles last month, when she got the audience to get up and dance with her to a Rihanna song.

She, her cast and crew had regular dance parties during the production of Hamnet. So for our NPR photo shoot and interview at a Beverly Hills hotel, I invited her to share some music from her playlist. She chose a track she described as “drones and tones.”

Our photographer captured her in her filmy white gown, peeking contemplatively from behind the filmy white curtains of a balcony at the Waldorf Astoria.

Zhao says she believes in ceremonies and rituals, and makes them a part of her filmmaking process.

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

Then Zhao and I sat down to talk.

“I had a dream that we were doing this interview,” I told her. “And it started with a photo shoot, and there was a glass globe –”

“No way!” she gasped.

It so happens that on the desk next to us, was a small glass globe — perhaps a paperweight.

I told her that in my dream, she was looking through the globe at some projected images. “We were having fun and it was like we didn’t want it to stop,” I said.

“Oh, well, me and the globe and the lights on the wall: they’re all part of you,” Zhao said. “They’re your inner crystal ball, your inner Chloé.”

“Inner Chloé?” I asked. “What is the inner Chloé like?”

“I don’t know, you tell me,” she said. “Humbly, from my lineage and what I studied is that everything in a dream is a part of our own psyche.”

Dreams and symbols are very much a part of Zhao’s approach to filmmaking, which she describes as a magical and communal experience. She said it’s all part of her directing style.

Chloé Zhao used painting and dance to connect with actors on the set of her latest film Hamnet.

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

“If you’re captain of any ship, you are not just giving instructions; people are also looking to you energetically as well,” she explained. “Whether it’s calmness, it’s groundedness, it’s feeling safe: then everyone else is going to tune to you.” Zhao says it has taken many years to get to this awareness. Her own journey began 43 years ago in Beijing, where she was born. She moved to the U.S. as a teen, and studied film at New York University where Spike Lee was one of her teachers. She continued honing her craft at the Sundance Institute labs — along with her friend Ryan Coogler and other indie filmmakers.

Over the years, Zhao’s film catalogue has been eclectic — from her indie debut Songs My Brothers Taught Me, set on a Lakota Sioux reservation, to the big-budget Marvel superhero movie Eternals. She got her first best director Oscar in 2021 for the best picture winner Nomadland. Next up is a reboot of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

“A creative life,” she notes, “is not a linear experience for me.”

Zhao still lingers over the making of Hamnet, a very emotional story about the death of a child. During the production, Zhao says she used somatic and tantric exercises and rituals to open and close shooting days.

She also invited her lead actors Paul Mescal and Jessie Buckley to help her set the mood on set. They danced, they painted, they meditated together.

“She created an atmosphere where everybody who chose to step in to tell this story was there for a reason that was deeply within them,” actress Jessie Buckley told me.

Buckley is a leading contender for this year’s best actress Oscar. She said that to prepare for her very intense role as William Shakespeare’s wife, Zhao asked her to write down her dreams “as a kind of access point, to gently stir the waters of where I was feeling.”

Buckley sent Zhao her writings, and also music she felt was “a tone and texture of that essence.”

That kind of became the ritual of how they worked together, Buckley said. “And not just the cast were moving together, but the crew were and the camera was really creating dynamics and a collective unconscious.”

Filmmaker and Hamnet producer Steven Spielberg calls Zhao’s empathy her superpower.

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Bethany Mollenkof for NPR

That was incredibly useful for creating Hamnet — a story about communal grief. Steven Spielberg, who co-produced the film, called Zhao’s empathy her superpower.

“In every glance, in every pause and every touch, in every tear, in every single moment of this film, every choice that Chloé made is evidence of her fearlessness,” Spielberg said when awarding Zhao a Directors Guild of America award. “In Hamnet, Chloé also shows us that there can be life after grief.”

Zhao says it took five years and a midlife crisis for her to develop the emotional tools she used to make Hamnet.

“I hope it could give people a two-hour little ceremony,” she told me. “And in the end, I hope that a point of contact can be made. That means that there’s a heart opening. But it will be painful, right? Because when your heart opens, you feel all the things you usually don’t feel. And then a catharsis can emerge.”

As our interview time came to a close, I told Zhao I have my own little ritual at the end of every interview; I record a few minutes of room tone, the ambient sound of the space we’re in. It’s for production purposes, to smooth out the audio.

Zhao knew just what I meant. She told me a story about her late friend Michael “Wolf” Snyder who was her sound recordist for Nomadland. “He said to me, ‘I don’t always need it, but just so you know, I am going to watch you. And when I tell that you are a little frazzled, I’m going to ask for a room tone … just to give you space.’” she recalled. “‘And if you feel like you need the silence space, you just look at me, nod. I’ll come ask for a room tone.’”

I closed our interview ceremony with that moment of silence, a moment of peace, for director Chloé Zhao.

Lifestyle

This spring, have a tea ceremony inside of an art installation and shop the latest Givenchy

Givenchy by Sarah Burton introduces the Snatch

Givenchy’s “The Snatch” handbag.

(Marc Piasecki / Getty Images)

Echoing the designer’s ready-to-wear sculptural designs, the Snatch from Givenchy by Sarah Burton is sensually shaped by the contours of the person who carries it. Its supple leather, fluid silhouette and three sizes allow it to slip effortlessly and intimately into the hand, over the shoulder or across the body. Now available. givenchy.com

Guess Jeans opens new L.A. store

Guess Jeans store interior.

(Josh Cho)

In a move familiar to many millennials these days, Guess Jeans has returned home in its 45th year. The new flagship store in West Hollywood is both a return to its California roots and an envisioning of its future still ahead. While the brand may be an established icon, the store boldly reimagines the retail space as a living laboratory for design, craftsmanship and collaboration, with dedicated workshop and customization spaces. 8700 Melrose Ave., Los Angeles. guess.com

Louis Vuitton’s new Color Blossom collection

Louis Vuitton’s new Color Blossom collection highlights sodalite.

(Louis Vuitton)

Taylor Swift’s sky may be opalite, but the starry blue hues in the new jewels of Louis Vuitton’s Color Blossom collection belong to sodalite. Rarely used in jewelry, the dark navy of sodalite adds an unexpected layer of depth to Color Blossom’s existing luminous gemstone lineup. Sun and star motifs rendered in gold enhance the gem’s night sky coloring, while the classic flower designs celebrate the 130th anniversary of the Louis Vuitton Monogram. Sodalite pieces available March 6, entire collection available April 4. louisvuitton.com

Loro Piana debuts Library of Knits

Loro Piana’s Library of Knits comes in over 20 shades.

(Lora Piana)

L.A.’s (many) winter showers bring spring wildflowers, and a bouquet of Loro Piana’s new Library of Knits fits right into the vibrant spectacle. The exquisitely soft cashmere pieces in classic styles now come in over 20 shades inspired by Sergio Loro Piana’s personal wardrobe. With a spectrum ranging from blues and greens to corals and creams, it’s hard to choose just one for a frolic in the fields. Now available. loropiana.com

Margesherwood X Peanuts

The Margesherwood X Peanuts collaboration features instantly recognizable motifs.

(Marge Sherwood)

Love is famously in the air this time of year, apparently even for cartoon characters. This enduring love is illustrated (literally) in the Margesherwood X Peanuts collaboration. Inspired by the heart-fluttering love letters Sally writes to Linus, the designs feature instantly recognizable motifs that marry the Peanuts’ charm with Margesherwood’s refined silhouettes. The zig-zag of that famous yellow shirt winkingly graces a crescent baguette, while the black stripes of Linus’s red red shirt wrap around a slouchy shoulder bag. For the true heads and lovers, there’s even a petite hobo emblazoned with Sally’s pet name for Linus: “FOR MY SWEET BABBOO.” Now available. margesherwood.com

Ryan Preciado at Hollyhock House

Ryan Preciado’s site-responsive “Diary of a Fly” at Hollyhock House features Oaxacan-woven textiles.

(Roman Koval)

Ryan Preciado’s new site-responsive installation at Hollyhock House, “Diary of a Fly,” is titled after a late-1930s musical composition by Béla Bartók that imitates the frenzied pace of a fly — a fitting name since his show reconceptualizes the experience of the springtime pest flitting around a house. Instead of hovering around overripe fruit or stalking a trash can long neglected, however, viewers are invited to take in Preciado’s Oaxacan-woven textiles and brightly colored sculptures situated throughout the city’s only UNESCO World Heritage Site. Open through April 25. 4800 Hollywood Blvd., Los Angeles. hollyhockhouse.org

Veronica Fernandez at Anat Ebgi

Veronica Fernanadez’s “Prey” filters childhood memories through experience and emotion.

(Veronica Fernandez)

In the figurative paintings of Veronica Fernandez’s first solo exhibition, “Prey,” the artist’s childhood is recalled through dreamlike and fantastical scenes, with memories filtered through experience and emotion. Many of her works place a child at the center of the scene among family, friends and caretakers, who usually appear shadow-like at the edges of the paintings. As a kid, Fernandez endured periods of homelessness. But rather than depict a childhood of adversity, her paintings empower the kids within them to claim their own space, imbuing her memories with strength and light. Open through April 4. 6150 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles. anatebgi.com

Dior launches J’Adore Intense

Dior’s J’Adore Intense captures the scent of solar flowers with Rihanna as its muse.

(J’Adore)

Florals for spring can be groundbreaking, especially when they’re created with none other than Rihanna as their muse. Dior’s J’Adore Intense captures the scent of solar flowers — jasmine, ylang-ylang, rose, violet — right before they burst into fruit. The result is a warm, bold, addictive fragrance that drips with sensuality and femininity, down to the curves of its signature gold and glass figure-eight amphora. In other words, it’s Rihanna in a bottle. Available now. dior.com

Rocky’s Matcha X Oscar Tuazon at Morán Morán

Rocky’s Matcha hosts Japanese tea ceremonies in an ensō-inspired tea house from Oscar Tuazon at Morán Morán.

(Stade New York)

The single, uninhibited brushstroke of the ensō, the circular form in Zen art, serves as a record of a moment. Commissioned by Rocky’s Matcha, Oscar Tuazon’s “Circle House” at Morán Morán shares both the ensō’s form and its call to mindfulness. In the artist’s tea house, constructed from cardboard, wood and tatami mats, architecture is inseparable from ritual: visitors will soon be able to partake in a Japanese tea ceremony inside the installation, thereby participating in a choreography of attention not unlike the act of gliding an ink brush across a sheet of washi. Open through December 31. 641 N. Western Ave. Los Angeles. Subscribe to rocky’s newsletter for tea ceremony information. rockysmatcha.com and moranmorangallery.com

Celebrate Mr. Wash’s new book, “Artists in Space”

Celebrate the launch of Mr. Wash’s new book of studio visits and interviews with other L.A. artists.

(Mr Wash)

Make your first BBQ of the season a meaningful one at the Art By Wash Studio & Community Center, where Compton artist and criminal justice advocate, Mr. Wash, will celebrate the release of his book “Artists in Space.” Proceeds from the book, which features interviews and studio visits with 20 Angeleno residents, go toward establishing the new community center where individuals returning home from incarceration will have access to art classes, creative residencies and housing. Mr. Wash will be in conversation with Patrisse Culllors and Evan Pricco (co-publisher and founder of the Unibrow) as well as displaying new works. The event is on March 7 from 2-6 p.m. 15 W. Rosecrans Ave., Compton. artbywash.com

Lifestyle

‘Hamnet’ star Jessie Buckley looks for the ‘shadowy bits’ of her characters

Jessie Buckley has been nominated for an Academy Award for best actress for her portrayal of William Shakespeare’s wife in Hamnet.

Kate Green/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Kate Green/Getty Images

Actor Jessie Buckley says she’s always been drawn to the “shadowy bits” of her characters — aspects that are disobedient, or “too much.” Perhaps that’s what led her to play Agnes, the wife of William Shakespeare, in Hamnet.

Buckley says the film, which is based on Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, offered a chance to counter a common narrative about the playwright’s wife: that she “had kept him back from his genius,” Buckley says.

But, she adds, “What Maggie O’Farrell so brilliantly did, not just with Agnes and Shakespeare’s wife, but also with Hamnet, their son, was to bring these people … and give them status beside this great man. … [And] give the full landscape of what it is to be a woman.”

The film is nominated for eight Academy Awards, including best actress for Buckley. In it, she plays a woman deeply connected to nature, who faces conflicts in her marriage, as well as the death of their son Hamnet.

Buckley found out she was pregnant a week after the film wrapped. She’s since given birth to her first child, a daughter.

“The thing that this story offered me, that brought me into this next chapter of my life as a mother was tenderness,” she says. “A mother’s tenderness is ferocious. To love, to birth is no joke. To be born is no joke. And the minute something’s born into the world, you’re always in the precipice of life and death. That’s our path. … I wanted to be a mother so much that that overrode the thought of being afraid of it.”

Jessie Buckley stars as Agnes and Joe Alwyn plays her brother Bartholomew in Hamnet.

Courtesy of Focus Features/Courtesy of Focus Features

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Focus Features/Courtesy of Focus Features

Interview highlights

On filming the scene where she howls in grief when her son dies

I didn’t know that that was going to happen or come out, it wasn’t in the script. I think really [director] Chloé [Zhao] asked all of us to dare to be as present as possible. Of course, leading up to it, you’re aware this scene is coming, but that scene doesn’t stand on its own. By the time I’d met that scene, I had developed such a deep bond with Jacobi Jupe, who plays Hamnet, and [co-stars] Paul [Mescal] and Emily Watson, and all the children and we really were a family. And Jacobi Jupe who plays Hamnet is such an incredible little actor and an incredible soul, and we really were a team. …

The death of a child is unfathomable. I don’t know where it begins and ends. Out of utter respect, I tried to touch an imaginary truth of it in our story as best I could, but there’s no way to define that kind of grief. I’m sure it’s different for so many people. And in that moment, all I had was my imagination but also this relationship that was right in front of me with this little boy and that’s what came out of that.

On what inspired her to pursue singing growing up

I grew up around a lot of music. My mom is a harpist and a singer and my dad has always been passionate about music, so it was always something in our house and always something that was encouraged. … Early on, I have very strong memories of seeing and hearing my mom sing in church and this quite intense mercurial conversation that would happen between her, the story and the people that would listen to her. And at the end of it, something had been cracked between them and these strangers would come up with tears in their eyes. And I guess I saw the power of storytelling through my mom’s singing at a very young age, and that was definitely something that made me think I want to do that.

On her first big break performing as a teen on the BBC singing competition I’d Do Anything — and being criticized by judges about her physical appearance

I was raw. I hadn’t trained. I had a lot to learn and to grow in. I was only 17. I think there was part of their criticism which I think was destructive and unfair when it became about my awkwardness, or they would say I was masculine and send me to kind of a femininity school. … They sent me to [the musical production of] Chicago to put heels on and a leotard and learn how to walk in high heels, which was pretty humiliating, to be honest, and I’m sad about that because I think I was discovering myself as a young woman in the world and wasn’t fully formed. … I was different. I was wild, I had a lot of feeling inside me. I could hardly keep my hands beside myself and I think to kind of criticize a body of a young woman at that time and to make her feel conscious of that was lazy and, I think, boring.

On filming parts of the 2026 film The Bride! while pregnant

I really loved working when I was pregnant. I thought it was a pretty wild experience, especially because I was playing Mary Shelley and I was talking about [this] monstrosity, and here I was with two heartbeats inside me. Becoming a mom and being pregnant did something, I think, for me. My experience of it, it’s so real that it really focuses [me to be] allergic to fake or to disconnection.

Since my daughter has come and I know what that connection is and the real feeling of being in a relationship with somebody … as an actress, it’s very exciting to recognize that in yourself and really take ownership of yourself.

I’m excited to go back and work on this other side of becoming a mother in so many ways, because I’ve shed 10 layers of skin by loving more and experiencing life in such a new way with my daughter. I’m also scared to work again because it’s hard to be a mother and to work. That’s like a constant tug because I love what I do and I’m passionate and I want to continue to grow and learn and fill those spaces that are yet to be filled — and also be a mother. And I think every mother can recognize that tug.

On the possibility of bringing her daughter to travel with her as she works

I haven’t filmed for nearly a year and I cannot wait. I’m hungry to create again. And my daughter will come with me. She’s seven months, so at the moment she can travel with us and it’s a beautiful life. And she meets all these amazing people and I have a feeling that she loves life and that’s a great thing to see in a child. And I hope that’s something that I’ve imparted to her in the short time that she’s been on this earth is that life is beautiful and great and complex and alive and there’s no part of you that needs to be less in your life. You might have to work it out, but it’s worth it.

Lauren Krenzel and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Denver, CO6 days ago

Denver, CO6 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Louisiana1 week ago

Louisiana1 week agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Oregon4 days ago

Oregon4 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Florida2 days ago

Florida2 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoArturia’s FX Collection 6 adds two new effects and a $99 intro version

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: How Lunar New Year Traditions Take Root Across America