Business

The WGA and AMPTP are talking again. Why the studios were motivated to return to the table

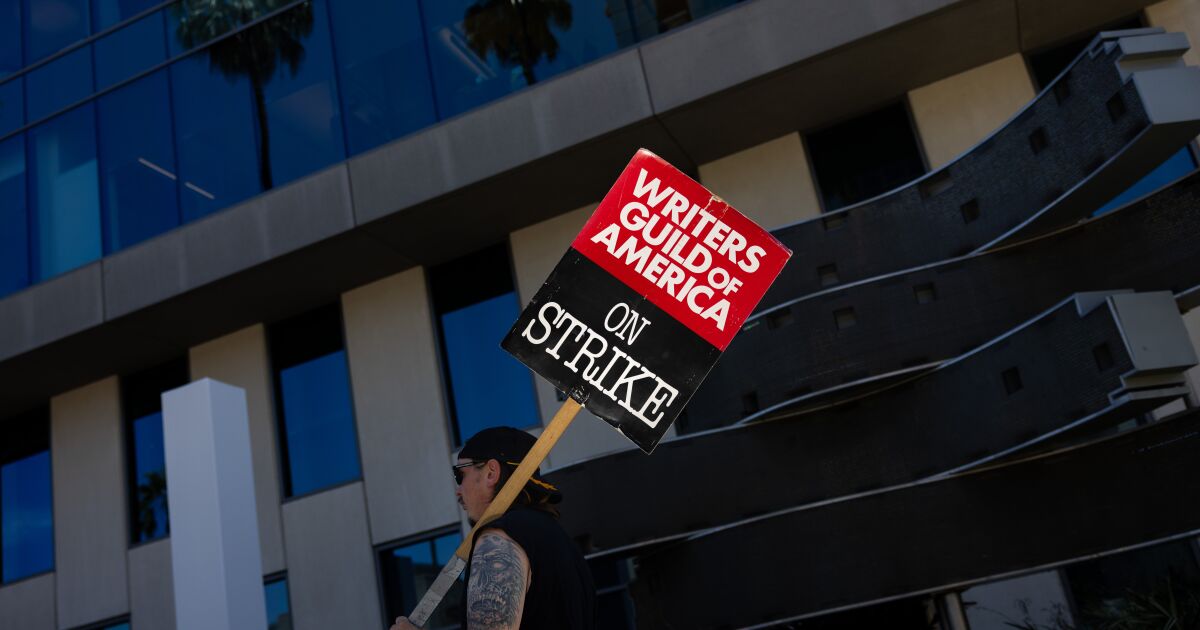

When film and television writers went on strike 108 days ago, most assumed the studios and streamers would hunker down for a long fight.

The companies, many of which are saddled with debt, could save money by cutting costly producer deals and pausing production of movies and TV shows. Industry news outlet Deadline quoted an anonymous executive who suggested that studios were ready to hold out until writers started losing their homes, which stoked outrage on picket lines.

As the negotiations resume, it’s still uncertain how much the Writers Guild of America and the studios are willing to bend to reach a compromise, or what precise shape a deal wouldtake. Sources close to the negotiations say the sides remain far apart on key issues.

But it’s become increasingly clear that the major studios and streamers, represented by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, are motivated to end the work stoppages that have roiled Hollywood. The SAG-AFTRA actors’ union joined the WGA by going on strike last month.

What changed? Several factors have prompted a new sense of urgency, according to interviews with multiple people close to the negotiations who were not authorized to comment.

The actors’ strike dramatically upped the stakes, wreaking havoc on production plans and creating more economic uncertainty for the major companies, including streaming giant Netflix, the Walt Disney Co., Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global and NBCUniversal.

The economic reverberations have been felt throughout the city, with businesses including prop houses and other small firms struggling to make ends meet, prompting politicians such as Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass to demand an end to the strikes.

“With each day that goes on, the economic damage is further intensified,” said Todd Holmes, associate professor of entertainment media management at Cal State Northridge, who estimated that the economic damage of the dual strikes on California was at least $3 billion so far and that it could balloon to $4 billion to $5 billion if the strikes were to stretch into October.

Media executives, many of whom remember the bruising writers’ strike 15 years ago, have insisted that they never wanted a prolonged fight, for these very reasons. The chief executives also recognized that they needed to be more involved after weeks of little progress.

Netflix co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos and Sony Pictures chief Tony Vinciquerra were initially among the most active executives to try to facilitate compromises, but in the last two weeks other leaders, including Universal’s Donna Langley and CBS Chief Executive George Cheeks — have helped to find common ground among the various companies.

Disney Chief Executive Bob Iger has also taken a more active role, along with producer and former studio chief Peter Chernin, who played a prominent role in the previous writers’ strike.

In recent weeks, movie studio executives have grown increasingly worried about the threat to their 2024 release slates. The studios need A-list talent to help them promote their projects, and they need to finish the ones in production. Sony recently pushed back the release of films including “Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse.”

“You don’t want to give the audience more reasons to leave,” said one veteran executive.

Streamers are also under pressure, but for their own reasons.

Netflix’s Sarandos has advocated for renewing talks, sources say, despite the fact that many writers blame his company for fueling the labor dispute, which some have dubbed the “Netflix strike.”

Also, the writers’ strike has shined a harsh light on labor tensions Netflix is facing in such countries as Korea, home of the popular series “Squid Game.” Korean artists, including actors and writers such as “Squid Game” creator Hwang Dong-hyuk, are pushing Netflix for more pay for creators — echoing demands of writers marching outside the company’s Sunset Boulevard offices.

In earnings presentations this year, Sarandos has struck a conciliatory tone, saying he was “super committed” to getting agreements done. Other executives have taken a similar tack to tamp down the rhetoric. Iger, who previously took heat for describing union demands as “not realistic,” more recently told investors that he was “personally committed” to finding solutions to the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes.

The alliance that represents the major studios met with the WGA negotiating committee Tuesday, during which the union responded to the companies’ latest proposals. The AMPTP declined to comment. The WGA has not commented on any of specifics of the alliance’s new offer.

Union members such as “The Wire” creator David Simon have warned fellow writers against trusting press leaks from studio sources, calling such disclosures “tactical.”

There has been movement on two major sticking points, sources said, raising hopes that the two sides might finally find a path to a deal.

The WGA has demanded that there be a minimum number of staffing for TV series writers’ rooms. Writers said they have suffered economically as the number of episodes in a season has gotten shorter on streaming services, with fewer writers involved in development.

Studios have attempted to address that issue in their latest proposal, which indicates a step forward. Variety reported that showrunners would get “significant authority to set the size of the staff,” factoring in a show’s budget. It is not clear, however, that such a system would sufficiently address the WGA’s concerns.

The topic is fraught for studios, in part, because they don’t want writers to set quotas on the number of people the companies must hire. Studio executives said some writer-producers have indicated that they want more flexibility to determine their own staffing needs.

Studio executives say they want a solution that would allow some leeway while providing more opportunities for early-career writers to be more involved in the process to learn what it takes to run a show.

Streamers also have been criticized by actors and writers for not providing enough data to explain how they determine success. Writers are seeking a payment system that would reward them financially in the event that their shows were to succeed. The studios offered to share data on how many hours people watched programs on streaming services, Bloomberg first reported.

Despite glimmers of hope, the strikes drag on.

Bryan Behar, a writer, executive producer and showrunner on “Fuller House,” posted on social media this week that while a lot of his enthusiasm had gone after 106 days of striking, his “resolve” hadn’t gone away.

“And it won’t,” Behar posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, with a selfie at the Fox lot. “Not until the AMPTP steps up to make a fair deal. Hasn’t happened yet.”