Lifestyle

‘That’s Why I Picked a Younger Man’

The day after Thanksgiving, my mother called, worried I was going to die. I had mistakenly told her that I had heartburn, so she left a long voice mail reminding me of how my father had heartburn before he died of a heart attack at 50 while playing racquetball.

She pleaded with me to get a checkup, to get my blood work done. “Did you know you’ve been gaining weight lately?” she said.

I knew.

Her voice started to break by the end of the message. I was her only son, and the men in her life tended to drop dead without warning, explanation or goodbye.

The day after my mother’s 80th birthday, her partner of more than 35 years, a man named Bing (who came after my father) died on a trip to Palm Springs with his friends, drowning alone in a hot tub at night with hypertension and alcohol as contributing factors.

Bing was like a father to me, yet he never imposed himself like stepfathers on TV. Even after he moved in when I was 5, he never disciplined me or gave fatherly lectures. Rather, he taught me how to fish on California’s Kern River and built me a huge treehouse in the backyard.

After Bing’s military burial by Marine veterans on a low hill outside of Bakersfield, my mother asked me to take her to Hawaii to visit her older sister who lives there with her daughter.

She had made a similar journey after my father died, a trip to paradise to get away from home and yet be close to the people who knew her partners and had stories to tell.

When my mother had explained Bing’s death to her neighbors of over 40 years, the husband said, “Isn’t that the second one you’ve lost?”

“He wasn’t supposed to die first!” she told me before our flight. “That’s why I picked a younger man; he wouldn’t do to me what your father did.”

This wasn’t the plan, for her or for me. Bing, just 73 when he died, was supposed to take care of her, keep the house in good shape and take out the trash.

In the 1960s, my mother and her sisters immigrated to Los Angeles after their home country of Indonesia fell into brutal conflict following Dutch decolonization. My mother had been raised with the belief that a woman’s job was to marry well and raise children. After my father died, she would often say, “No one taught me what to do if my husband kicked the bucket.”

As the only man left in her life, I flew her to Hawaii to heal her pain, and I used promises of beaches and snorkeling to persuade my husband to come too. I told him a vacation is what we need after all the sadness, and he sweetly agreed.

My aunt lives with my cousin and my cousin’s husband on the rainy Hilo side of the Big Island, where all the good hotels were booked, so the three of us ended up sharing one room in a motel with two beds and a struggling air-conditioner. It rained every day. When we weren’t visiting my relatives, we sat in bed eating takeout and watching TV.

My husband tried to stay cheerful, but the rain, my grieving mother and cramped quarters were a bit much. At night, my mother would cry out for Bing in her dreams.

I was desperate to make things better. My chest felt tight, but I ignored it. I wanted the healing to begin; this was Hawaii, after all. So we cut the visit to Hilo short, and I booked a condo on the sunny side of the island in Waikoloa.

As we drove over the crest of ancient volcanoes, the sun emerged, making the ocean glitter below. Our condo had two bedrooms and enough space to hide from each other, and it was on a golf course where wild turkeys roamed. That night, we fed them from our hands and felt some of the Hawaiian magic we had been looking for.

The next day, when we finally found ourselves on a white sandy beach, strange clouds began drifting overhead. They were dark and low and made me want to get somewhere safe.

Turns out a wildfire had broken out and strong winds were pushing the smoke our way. It became difficult to breathe, so we hunkered indoors watching the Tokyo Olympics.

“I didn’t come to Hawaii to watch TV,” my husband said on day two of the wildfire. We started arguing. My mother was grieving, and I felt like I couldn’t leave her alone. Yet I knew the trip was not turning out as promised.

Suddenly, all three of our phones blared an emergency message. Waikoloa Village, 15 minutes away by car, was being evacuated. We were told to prepare for possible evacuation too.

“Am I being punished by God?” my mother said, looking at the smoke. “Where do we evacuate to? The beach?” She sighed and went back to the TV, turning up the volume.

My husband marched into our bedroom and shut the door. He said that he was going out for a walk, that he didn’t care about the smoke, and that I better figure out something to do that wasn’t watching canoe races or horse jumps.

After he left, the tightness in my chest that I’d been trying to ignore sharpened and moved into my neck and jaw. I’d felt something like it before, but since Bing’s death, the pain had gotten worse. I thought it was my heart, but I couldn’t tell anyone. I was there to heal my mother and give my husband a romantic Hawaiian adventure.

I laid down on the bedroom carpet and covered my eyes with the palms of my hands. I focused on big slow breaths until finally the pain subsided and I could stand and join my mother on the couch.

She kept a running commentary on which Olympic athletes she liked and which were showoffs. It was a familiar rhythm that I remembered from childhood, just the two of us watching TV, talking about everything and nothing. Then she said, “Bing wasn’t your father, but he loved you like a son. He took care of us the best he could.”

“I know, Mom,” I said. “I know.”

The next day the firefighters got the upper hand and evacuation orders were lifted. We salvaged what we could of our final days and were grateful to go home.

Weeks later, I went to my doctor. He told me my chest pains were mini-panic attacks but that my heart was OK. “You need to manage your stress better,” he said. “Take more walks, get better sleep, maybe try losing some weight.”

I left wondering if he and my mother were talking about me. I thought about my father and Bing, both gone. My father’s fate had always hung over me like a warning. Now Bing’s fate warned me not to waste a single minute.

It had been sunny and warm at Bing’s funeral. I remembered sweating as a group of us carried his coffin from the hearse. Even though my mother was supposed to go back to her seat, she remained by Bing’s coffin after she went up to kiss it.

Bing had a world of friends at the funeral who we didn’t know — fishing buddies, high school classmates and service members. Without prompting, my mother embraced every mourner as they came to pay their respects, as if she knew them.

I went to stand next to her as she did this, feeling like I was intruding on some other family’s grief, and I was amazed by how my mother let it all out, crying and talking to so many strangers. This wasn’t a part of the plan, either. My mother had just done it, surprising herself as much as the rest of us.

“I don’t know why I’m standing here,” she said as she held hands with one of Bing’s friends. “We all loved him so much, and now he’s gone, but our love is still here.”

Only looking back did I realize that my panic attacks were borne from my need to control life’s calamities and the feeling that I was failing to fix what couldn’t be fixed.

I loved Bing; I was grieving, too, and I had kept the grief at bay by trying to heal the heartache of those around me. But the pain had to come out, and it would be mixed with love, confusion and anger, and that was OK.

Having lost the second love of her life, my mother was awash with pain. Yet there she was, teaching us how to grieve. And I had almost missed the lesson.

Lifestyle

The first 'Jinx' ended with a hot mic murder admission. 'Part Two' shocks as well

Robert Durst was arrested in 2015, the night before HBO televised the final episode of The Jinx. He was later convicted of murder, and died in prison in 2022.

HBO

hide caption

toggle caption

HBO

Robert Durst was arrested in 2015, the night before HBO televised the final episode of The Jinx. He was later convicted of murder, and died in prison in 2022.

HBO

In 2014, the producers of This American Life presented a podcast called “Serial,” examining the facts, and loose ends, involving a cold murder case. A year later, HBO followed with a TV equivalent: The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst. Together, those two wildly popular programs helped ignite the true-crime documentary and podcast craze – a genre that itself became so imitated that it was spoofed by Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building.

The Jinx recounted the story of Robert Durst – a wealthy man suspected, over many decades, of the murders of several people. The documentary series was made with Durst’s cooperation – specifically, several on-camera interviews with filmmaker Andrew Jarecki. The final episode climaxed with some stunning remarks made by Durst while he was alone and talking to himself, still wearing a hot mic.

Durst was arrested the night before HBO televised the final episode of The Jinx, and later was convicted of murder, and died in prison in 2022. On April 21, Jarecki returns to HBO with a sequel documentary series, The Jinx – Part Two, which also will stream on Max. I highly recommend you see the original Jinx, first if you haven’t – it’s available on most streaming sites. But it’s not required.

The Jinx – Part Two is amazing right from the start, because filmmaker Jarecki never stopped filming. In the original series, it was the accidental recording of Durst, muttering to himself in a bathroom after Jarecki confronted him with a damning piece of physical evidence, that helped lead to the wealthy man’s arrest. The Jinx – Part Two swoops right back in, using phone wiretaps recorded by prosecutors, interviews with investigators and even conversations with witnesses on both sides at the trial – some cooperative, some hostile.

The Jinx – Part Two starts its behind-the-scenes narrative just as the original Jinx is days away from premiering on HBO. Events are captured in real time, revealing themselves like elements in a thriller.

Halfway through the run of the original Jinx, Durst, watching from home, is feeling kind of cocky. But then, because of a spelling error in his handwriting that seems to connect him to an anonymous note sent to police after one murder, he shifts gears. FBI agents and Los Angeles district attorneys track him withdrawing large sums of money, then fleeing before the final episode – but as The Jinx – Part Two shows, he’s cleverly tracked down in a New Orleans hotel, and captured.

LA deputy district attorney John Lewin is the first to interrogate to Durst in a recording that we see in The Jinx – Part Two. What follows is a story with as many twists, turns and shockers as the original. Jarecki is as good an interviewer as he is a director, and what he gets out of his conversations with people – from Durst’s friends and lovers to his investigators and prosecutors – is unexpected, and sometimes is almost laughably candid.

As it turns out, there’s a great story in the continued telling of the Robert Durst saga – and there are some lessons to be learned, too. Don’t commit murder. If you DO commit murder, don’t cooperate with a documentary filmmaker. And if you DO kill someone, and talk about it on camera, learn how to spell.

Lifestyle

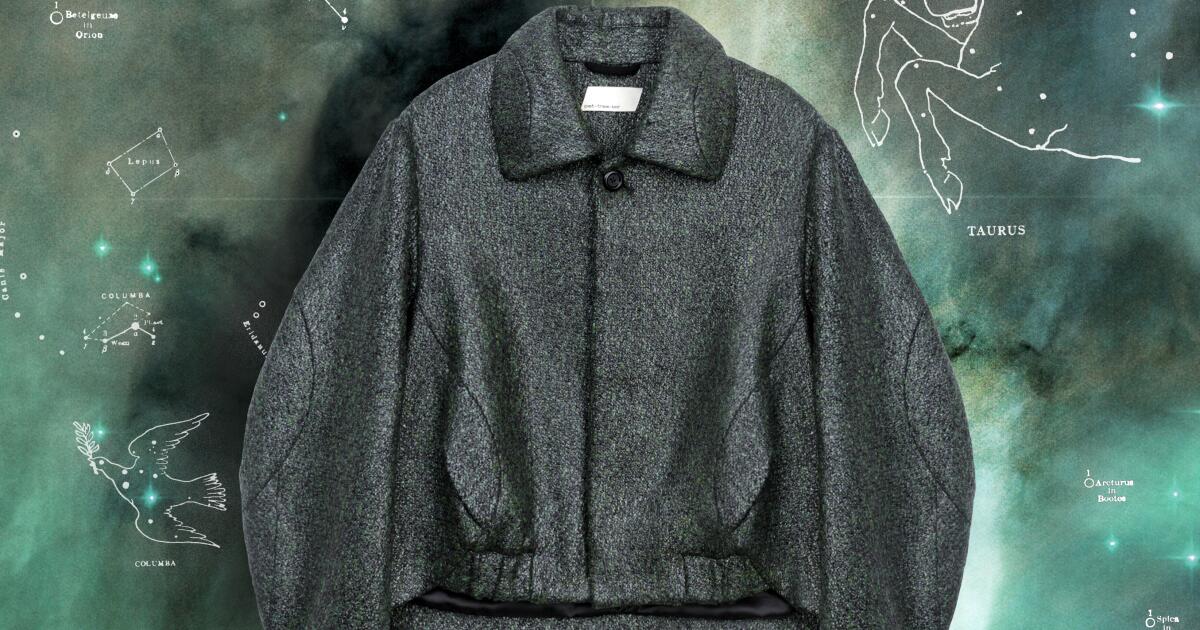

Here’s your fashion horoscope for what to wear this Taurus season

pet-tree-kor’s Green Helicteres Isora Jacket.

(Photo Illustration by Beth Hoeckel)

We find ourselves in that time of year dedicated to the most sensuous and worldly of the earth signs — that is, Taurus season. We are so grateful for our baby bulls, because they remind us that food, drink, sex and money exist to be experienced in all their glory. And what better way to indulge in all these things than by traveling? Liberate your carefully selected and impeccably preserved vintage designer purse strings (we’re talking Taurus, after all) and go somewhere.

The ritual of travel is as visceral as it is spiritual. It’s the sweat collecting under your collar while you speed-walk to your gate (just to make sure it’s there, right?) as much as it is a 4 a.m. kiss on a starry beach accessible only by motorcycle. And the ritual before the ritual — packing — becomes a delicate, fraught dance of selection, a personal curatorial Everest that requires the traveler to dream, first and foremost, of how rainy the breeze might be on the way up the Eiffel Tower, how they might dress for both a rooftop dinner and a volcanic hike just outside San Salvador, if they’ll long for a stiletto boot at the Beijing opera or be too entranced by the show to care that they brought the flats instead. The careful balance of environmental factors in wardrobe selection, however, comes secondary to the crown jewel of functionality: the all-purpose travel jacket.

Trip jacket selection is an art and a science, best done elegantly, with attention paid to form, function, aesthetics and viability — as a pillow when folded into fourths or eighths on a long-haul flight. It should be able to take you to a museum and a visit to the botanical gardens with street food in hand on the same day. For this, may I suggest pet-tree-kor’s Green Helicteres Isora Jacket. The Shanghai-based imprint’s name is a nod to “petrichor,” a functionally and mystically perfect word that exists solely to describe the divine perfume that greets your nostrils after a rain (a smell that, allegedly, humans can detect more astutely than a shark’s nose can detect blood).

This garment, rendered in a tweed blend with a gorgeously mossy sheen, is both architectural in its structure and fluid in its silhouette. It looks at once inviting and familiar — almost like your most gallant grandfather’s jacket from the days he used to go out dancing with your grandma — and polished and elegant. It wouldn’t look out of place in a cozy diner on a rainy night in San Francisco’s Chinatown or on a dewy morning at the Rhode Island beach house of your friend with generational wealth. The shade of the jacket is an oft-underrated neutral, pairing nicely with virtually any other piece in your suitcase, maybe even amethyst or royal blue too. The Helicteres isora, the jacket’s namesake, is a vibrant plant from northern Oceania whose leaves dry in tawny-green curlicues, like nature’s fractals.

And nature’s most esoteric fractal you shall be in your pet-tree-kor travel jacket, cruising through the liminal space of LAX on the way to your next adventure. Does your manic pixie dream girl complex fantasize about an ethereal-looking stranger mesmerized in reverie as they gaze upon the dapples of fluorescent Tom Bradley terminal lights reflecting off this sumptuously swamp-hued fabric? Mine too. For all the grounding and presence that resets our nervous systems, our earthly vessels would be naught without the dream of a shimmery green.

Goth Shakira is a digital conjurer based in Los Angeles.

Lifestyle

What's Making Us Happy: A guide to your weekend viewing, listening and gaming

This week, Taylor Swift delivered some tortured poets, Quentin Tarantino changed his mind, and at least one Oscars hangover went on and on and on.

Here’s what NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour crew was paying attention to — and what you should check out this weekend.

Koreaboo, on Audible

Audible has a romantic fiction podcast called KoreaBoo that is too cute. Shayla is an English expat in Korea and you expect her to do the stereotypical romance thing and fall in love with a K-Pop idol, but she ends up falling for her landlord’s son. It’s incredibly cute and sweet and funny. It’s written by Shenee Howard. The episodes are about half an hour long — super easy, delightful, and so cheery. — Joelle Monique

The Wiz on Broadway

Wayne Brady as The Wiz

Jeremy Daniel

hide caption

toggle caption

Jeremy Daniel

Wayne Brady as The Wiz

Jeremy Daniel

I am delighted to say that the revival of The Wiz has brought me so much joy. I saw it in previews and it just opened on Broadway. It is a multicultural, multicolored delight. Folks who go to see it will be clamoring for the cast recording album because, more than anything, I think what stuck with me is just the wonderful vocal arrangements and orchestrations from this new version. I think people will really enjoy it. — Soraya Nadia McDonald

Balatro

YouTube

Balatro is a deck building video game, which means it’s basically poker that you play by yourself. You’re dealt this hand, and then you try to build straights and flushes and things of a kind, etc. What makes it addictive is its elegant simplicity: Between hands you get a chance to buy random Jokers and other cards that do different things. And as you go through each run, the amount of points you can get, you have to earn on that hand increase. So, once you don’t make it, that’s it. You start over, your Jokers go away, you start from zero. You keep playing, and playing, and playing, because moments happen when the Jokers you have assembled interact with each other, and when they do, you see the points multiplying exponentially and you feel completely invulnerable. Producer Liz Metzger mentioned this game so I checked it out and when I looked up, it was the next day. — Glen Weldon

More recommendations from the Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter

by Linda Holmes

Don’t miss Elizabeth Blair’s piece for NPR marking the 50th anniversary of Redbone’s “Come And Get Your Love.” It was the first song by an all-Native and Mexican American band to make it into the Billboard Top 10, and she collects some terrific reminiscences. It’s a really good piece both to read and to listen to.

At six million views on YouTube, the dance video of the CDK Company interpreting Gotye’s “Somebody That I Used To Know” is hardly a hidden gem. But the choreography is fascinating, and it’s highly recommended if you’re in the mood for a little mind-blowing movement.

The Hulu series Under The Bridge is based on the true story of a Victoria, B.C. teenager who was killed after going off to meet a bunch of other teenagers. And while that’s a dynamic that’s been explored before (going back at least to River’s Edge), this is also an opportunity for recent devotees of Lily Gladstone to see her play the cop who’s determined to figure out what happened. Riley Keough plays a journalist who grew up in Victoria and has returned to write a book, only to get very much mixed up in the case.

Beth Novey adapted the Pop Culture Happy Hour segment “What’s Making Us Happy” for the Web. If you like these suggestions, consider signing up for our newsletter to get recommendations every week. And listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWhat to know about the Arizona Supreme Court's reinstatement of an 1864 near-total abortion ban

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans blast 'cry wolf' conservatives who tanked FISA renewal bill

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Biden Hosts Japan’s Prime Minister at the White House

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRomania bans gambling in small towns

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoKentucky governor vetoes sweeping criminal justice bill, says it would hike incarceration costs

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago'Very tense' situation as floods in Russia see thousands evacuated

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoArizona says century-old abortion ban can be enforced; EPA limits 'forever chemicals'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBiden, Japan leader Kishida announce stronger defence ties in state visit