Business

Will the Metaverse Be Entertaining? Ask South Korea.

In an enormous studio outdoors Seoul, technicians huddled in entrance of screens, watching cartoon Ok-pop singers — at the least one in every of whom had a tail — dance in entrance of a psychedelic backdrop. A lady with fairy wings fluttered by.

Everybody onscreen was actual, form of. The singers had human counterparts within the studio, remoted in cubicles, with headsets on their faces and joysticks in each fingers. Immersed in a digital world, they had been competing to grow to be a part of (hopefully) the subsequent massive Korean lady band.

The stakes had been excessive. Just a few of their opponents, after failing to make the lower, had been dropped into effervescent lava.

This, some say, is the way forward for leisure within the metaverse, delivered to you by South Korea, the world’s testing floor for all issues technological.

“There are lots of people who need to get into the metaverse, however it hasn’t reached important mass, users-wise, but,” mentioned Jung Yoon-hyuk, an affiliate professor at Korea College’s Faculty of Media and Communication. “Different locations need to enterprise into the metaverse, however to achieve success, you want to have good content material. In Korea, that content material is Ok-pop.”

Within the metaverse — no matter that’s, precisely — the conventional guidelines don’t apply. And the Korean leisure business is delving into the chances, assured that followers will fortunately observe.

Ok-pop teams have had digital counterparts for years. Karina, a real-life member of the band Aespa, could be seen on YouTube chatting along with her digital self, “ae-Karina,” in an trade that comes off as seamlessly as late-night TV.

The Korean firm Kakao Leisure desires to take issues additional. It’s working with a cell gaming firm, Netmarble, to develop a Ok-pop band known as Mave that exists solely in our on-line world, the place its 4 synthetic members will work together with real-life followers all over the world.

Kakao can also be behind “Lady’s Re:verse,” a Ok-pop-in-the-metaverse present, whose debut episode on streaming platforms this month was seen greater than one million occasions in three days. For each tasks, Kakao is considering album releases, model endorsements, video video games and digital comics, amongst different issues.

The origins. The phrase “metaverse” describes a totally realized digital world that exists past the one through which we dwell. It was coined by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel “Snow Crash,” and the idea was additional explored by Ernest Cline in his novel “Prepared Participant One.”

What Is the Metaverse, and Why Does It Matter?

In contrast with their Korean counterparts, media corporations in the US have solely engaged in “mild experimentation” with the metaverse to date, mentioned Andrew Wallenstein, the president and chief media analyst of Selection Intelligence Platform.

International locations like South Korea “are sometimes checked out like a take a look at mattress for the way the longer term goes to pan out,” Mr. Wallenstein mentioned. “If any development goes to maneuver from abroad to the U.S., I might put South Korea on the entrance of the road when it comes to who’s likeliest to be that springboard.”

South Korea’s experiments with digital leisure date again at the least 25 years, to the temporary life span of a man-made singer known as Adam. A baby of the ’90s, he was a pixelated creature of laptop graphics, with sweepy eye-covering bangs and a raspy voice that attempted a bit too exhausting to sound attractive. Adam disappeared from the general public eye after releasing an album in 1998.

However digital creations like him, or it, have been an indicator of Korean widespread tradition for a technology. At the moment, Korean “digital influencers” like Rozy and Lucy have Instagram followings within the six figures and promote very actual manufacturers, like Chevrolet and Gucci.

The influencers have been purposely made to look virtually actual, however not fairly; their near-human high quality is a part of their enchantment, mentioned Baik Seung-yup, Rozy’s creator.

“We need to create a brand new style of content material,” mentioned Mr. Baik, who estimated that about 70 % of the world’s digital influencers are Korean.

In line with McKinsey, greater than $120 billion was spent globally on growing metaverse know-how within the first 5 months of 2022. A lot of that got here from corporations working in the US, mentioned Matthew Ball, a tech entrepreneur who has written a ebook in regards to the metaverse.

The best-profile latest instance was when Fb renamed itself “Meta” in a multibillion-dollar try and embrace the subsequent digital frontier, solely to see its inventory tumble and its earnings decline.

The South Korean authorities is investing greater than $170 million to assist improvement efforts right here, forming what it calls a “metaverse alliance” that features a whole lot of corporations. Mr. Ball mentioned it is without doubt one of the most aggressive packages of its sort. However whereas South Korea could also be “leagues forward” with regards to artificial pop stars, whether or not its corporations are prone to take a number one position because the metaverse evolves “is an open query,” Mr. Ball mentioned.

Authorities backing for brand new applied sciences has paid off for South Korea prior to now. The nation constructed its fashionable economic system over the previous few many years on the backs of tech conglomerates and positioned a profitable wager on the cellphone business, laying the groundwork for it to grow to be what Bernie Cho, a music government in Seoul, known as “probably the most wired and wi-fi nation.”

Youngsters right here scroll by means of comics on telephones, devour numerous hours of Korean dramas and not using a cable field and zealously observe Ok-pop stars on social media and new platforms. On Zepeto and Weverse, followers work together with one another, generally as customizable avatars, and with their favourite bands.

Kakao Leisure — an arm of Kakao, South Korea’s do-everything tech firm — is billing Mave, its synthetic band in progress, as the primary Ok-pop group created completely inside the metaverse, utilizing machine studying, deep pretend, face swap and full 3-D manufacturing know-how. To present them international enchantment, the corporate desires the “women” of Mave to finally be capable of converse in, say, Portuguese with a Brazilian fan and Mandarin with somebody in Taiwan, fluently and convincingly.

The thought, mentioned Kang Sung-ku, a technical director for the venture, is that after such digital beings can simulate significant conversations, “no actual human will ever be lonely.”

Kakao’s singing present, “Lady’s Re:verse,” has a well-recognized reality-TV “survival” format: 30 singers, eradicated over time, till the final 5 standing type a band. However the contestants — all members of established Ok-pop bands or solo artists — compete, banter and hang around as avatars, in a digital world known as “W.” Their actual identities should not revealed till they go away the present (in some circumstances, by the use of the lava) or make it to the top.

There are few limits to the creativeness in “W,” which whisks its contestants from the open sea to a Versailles-like palace to a desert panorama. One avatar is a chocolate princess, born in a cocoa tree; one other has crimson satan horns. Pengsoo, a blunt-talking penguin mascot widespread in South Korea, is without doubt one of the judges.

The contestants had been concerned in creating their avatars, mentioned Son Su-jung, a producer for the present. She mentioned a part of the purpose was to provide Ok-pop singers — “idols,” as they’re known as — a break from the business’s relentless magnificence requirements, letting them be judged by their expertise, not their appears. (Although the avatars, it ought to maybe be mentioned, all have massive eyes and heart-shaped faces.)

The present additionally lets them drop their polished public personas, calm down and crack jokes. “Idols in the actual world are anticipated to be a product of perfection, however we hope that by means of this present, they’ll let go of these pressures,” Ms. Son mentioned.

At a latest taping, glitches had been nonetheless being ironed out. Help employees popped out and in of cubicles to assist singers fiddle with their tools. At the very least one mishap made it into the primary episode: “I can’t hear you!” a contestant yelled as a decide repeatedly requested her the identical query.

However some issues about actuality TV hadn’t modified. Even avatars, it seems, are inspired to snipe at their opponents.

“Take a look at the inexperienced mild,” a producer intoned by means of a microphone to a contestant, whose avatar stared again at him from the display.

“Who do you suppose did the worst?” he mentioned. “Discuss as in case you’re gossiping about somebody.”

Business

Avian flu outbreak raises a disturbing question: Is our food system built on poop?

If it’s true that you are what you eat, then most beef-eating Americans consist of a smattering of poultry feathers, urine, feces, wood chips and chicken saliva, among other food items.

As epidemiologists scramble to figure out how dairy cows throughout the Midwest became infected with a strain of highly pathogenic avian flu — a disease that has decimated hundreds of millions of wild and farmed birds, as well as tens of thousands of mammals across the planet — they’re looking at a standard “recycling” practice employed by thousands of farmers across the country: The feeding of animal waste and parts to livestock raised for human consumption.

“It seems ghoulish, but it is a perfectly legal and common practice for chicken litter — the material that accumulates on the floor of chicken growing facilities — to be fed to cattle,” said Michael Hansen, a senior scientist with Consumers Union.

It is still unclear how the cows were infected — whether by contact with birds, or via feed made from litter waste — but litter has been associated with previous outbreaks of disease, including botulism.

Poultry litter causing the bovine cases of avian flu is considered “very unlikely, though not impossible” wrote Veronika Pfaeffle, in a joint statement from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration.

Poultry litter consists of manure, feathers, spilled feed and bedding material that accumulate on the floors of the buildings that house chickens and turkeys. It can contain disease-causing bacteria, viruses (including H5N1), antibiotics, toxic heavy metals, pesticides and even foreign objects such as dead rodents, birds, rocks, nails and glass.

It is typically mixed with hay or corn to make it palatable to livestock.

California bans the feeding of poultry litter to lactating dairy cows. However, it is legal to sell it as feed to beef and other cattle.

“It is a premium product used to help recycle waste into a sustainable product,” said Anja Raudabaugh, CEO of Western United Dairies. She said that although she could not make informed comments about its use outside of the state, “there is very little of it used here in California.”

California’s animal feed law — which applies to commercially sold feeds — requires that animal waste products sold for feed must contain no residues of pathogens, metals, pesticides or antibiotics.

The Department of Food and Agriculture’s Feed Program “inspects every California facility manufacturing dried poultry litter and reviews firms’ treatment verification records onsite,” said Steve Lyle, department spokesman.

However, it is unclear whether there are regulations addressing the private exchange or production of poultry litter or other animal waste for feed. Or how widespread the practice of feeding poultry waste to cattle is in the state or around the country.

It “was a common practice throughout the U.S. for many years,” said Lyle. “It is not a very common practice in California anymore.”

Chicken litter cannot be fed to lactating dairy cows under California law.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

According to Michael Payne, a researcher and outreach coordinator at the Western Institute of Food Safety and Security at UC Davis, there was at least one commercial processor of poultry litter in the state — Imperial Western Products, based in Coachella. That company was bought in 2022 by Arkansas’ Denali Water Solutions — which has had recent legal run-ins with environmental authorities in Missouri and Alabama over its handling of animal waste. It is unclear whether Imperial still produces feed from litter. An operator at the company directed calls to “corporate,” or Denali Water Solutions, which is owned by TPG Growth, a private equity firm. Denali did not provide comments for this story before publication.

The federal government does not regulate poultry litter in animal feed, and in many states — including Missouri, Alabama and Arkansas — there are no requirements or regulations regarding contamination or processing.

“The FDA may take regulatory action if it becomes aware of food safety concerns with poultry litter products intended for use in animal food in interstate commerce,” Pfaeffle said in the statement from both the USDA and FDA.

An online guide from the University of Missouri notes there are “no federal or Missouri regulations governing the use of poultry litter as a feed.” However, the guide’s authors urge users to employ “common sense.”

“Poultry litter should not be fed to dairy cattle or beef cattle less than 21 days before slaughter,” the guide notes, citing concerns about “residues of certain pharmaceuticals.”

Most other developed nations — including Canada, the United Kingdom and the countries within the European Union — have banned the practice. The FDA considered doing so in the U.S. in the mid-2000s.

For cattle farmers, the waste — which includes calcium, zinc and other minerals and vitamins — provides a cheap form of protein feed. For poultry farmers, the exchange allows them to divert the litter away from a landfill or from being burned.

In the 1980s, concerns about bovine spongiform encephalopathy — or mad cow disease — took hold across Europe, when cases of the incurable and invariably fatal neurodegenerative disease of cattle began to appear. The disease, which is caused by folded proteins known as prions, can transfer to people who eat the meat of infected cattle. In people, the disease is fatal and called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Just as cattle are fed poultry waste, chickens are often provided feeds that consist of cattle waste and renderings — creating a potential route for prions to re-enter the food supply. However, because the FDA mandates the removal of all tissues shown to carry the prions — such as brains and spinal cords — from poultry diets, the risk is reduced.

However, other more common pathogens are also found in poultry litter. In one 2019 study of litter used on farm fields as fertilizer, researchers found that every sample tested from U.S. broiler chickens carried E. coli strains resistant to more than seven antibiotics — including amoxicillin, ceftiofur, tetracycline, and sulfonamide.

It is unclear if the litter was heat treated before it was applied.

Raudabaugh said all poultry litter feed in California is kiln heated and exposed to temperatures that can kill bacteria, such as E. coli, and viruses, including H5N1.

“Firms are sampling and analyzing finished product for Salmonella regularly,” said Lyle, the state’s food and agriculture spokesman.

He noted that poultry is regularly tested for bird flu and that poultry waste from a flock infected with bird flu “cannot leave the premises until it has met CDFA requirements for ensuring the virus has been eliminated,” he said. “The premises is also tested and the quarantine is not released until the premises tests negative for highly pathogenic avian influenza.”

Lyle said cattle herds with “symptoms consistent” with bird flu infections “can be tested at the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory in consultation with the CDFA Animal Health Branch.”

He added that no symptomatic herds have been identified, “although one herd that lost pregnancies was tested and was negative” for the virus.

Business

Column: L.A.'s ultimate heartbreak industry isn’t Hollywood. It's local journalism

Whenever I think of the perilous state of local news, I think of Delicious Pizza in West Adams.

Great pizza! Small space, cool atmosphere. In the fall of 2017, I found myself there along with other journalism castoffs cursing the news gods.

I had just resigned as editor of OC Weekly after I refused to lay off half the staff. Daniel Hernandez was out of a job at VICE News after nearly four years there. Julia Wick had led the original LAist until its owner shut down the website because he claimed it wasn’t economically successful. Former LA Weekly editor-in-chief Mara Shalhoup was axed alongside most of her writers and editors after a new owner acquired the venerable alt-weekly.

Over beers and slices, we laughed and shared stories and fretted about the eternal erosion that is American journalism. None of us were about to give up on our beloved profession, though. There was talk of creating our own publication, but nothing serious. Instead, we hugged and went on to the rest of our lives.

Today, Mara is ProPublica’s South editor. Daniel edits The Times’ food section. Julia is on The Times’ 2024 election team. I’m a Times columnista, of course, frequently using Southern California’s past as a prism to understand what’s happening now and what might occur in the future.

And boy, does it not look good for local journalism — again.

Last month, the nonprofit Long Beach Post, which expertly covered the port city while the Press-Telegram atrophied, laid off nearly everyone. The publication’s board of directors maintained the move was necessary to save it from financial ruin — but former staffers insist it was retribution for their attempt to form a union.

Reporters for Knock LA, which focuses on social justice issues and law enforcement corruption, accused the publication’s sponsors, the leftist group Ground Game LA, of exiling them after they asked to spin off Knock into its own standalone entity.

For the record:

4:09 p.m. April 17, 2024An earlier version of this article said that Ground Game LA is the fiscal sponsor of Knock LA. Knock LA is part of Ground Game LA, and the two organizations share funding.

In the for-profit world, L.A. Taco, which centers food coverage while covering working class communities across Southern California, furloughed nearly everyone on its small team. Editor-in-chief Javier Cabral said they would be laid off if the publication isn’t able to hit 5,000 members by the end of April. (They were at 2,800 as of Monday). This follows the shuttering of one of California’s oldest continuously operating newspapers, the Santa Barbara News-Press, last year.

And, of course, there’s this paper. More than 100 of my colleagues were laid off last summer and earlier this year. Others took buyouts, and it seems recently that farewell emails from colleagues moving on to other jobs or retiring hit my mailbox daily.

It’s easy to portray what’s going on in local media as unprecedented and catastrophic, especially in the face of similar layoffs nationwide during an election year where accurate facts and nuanced coverage matter more than ever. But Southern California has always been an ossuary of failed publications done in by apathetic readership, clueless owners or a combination of both.

A 2006 rally at De La Guerra Plaza in front of the Santa Barbara News-Press newspaper’s offices. The newspaper, one of the oldest in California, ceased publishing last year.

(Michael A. Mariant / Associated Press)

Every generation in L.A. seems to suffer a journalism mass extinction event. In addition to what’s happening right now and what happened in 2017, there was the shuttering of two alt-weeklies, Los Angeles CityBeat and the Long Beach-based The District Weekly, at the turn of the aughts. I remember the demise of La Banda Elastica and Al Borde, two Spanish-language publications that focused on rock en español through the late 1990s and 2000s. Older folks will remember the end of the L.A. Herald Examiner in 1989, whose grandiose downtown headquarters are now used as a satellite campus by Arizona State University.

L.A.’s heartbreak industry isn’t Hollywood; it’s journalism. To paraphrase what the late A. Bartlett Giamatti said about baseball, it’s designed to break the hearts of those who work it.

You join the profession knowing that long hours, low pay and no respect from the public is the norm, yet you jump in anyway. You revel in your colleagues, your shared sense of mission and the stories you do — but then the reality of economics sets in, and you realize the good times won’t last. You wonder why readers don’t subscribe, why editors and publishers don’t innovate. You see co-workers lose their jobs or leave the profession — and then it’s your turn, one way or another.

It’s easy to armchair quarterback why publications fail. Blame technology, fragmented audiences, a lack of trust in news — it’s all of that, and more. But these conditions existed before photos appeared in newspapers, and will persist long after whatever Elon Musk inserts in our brains so we can’t quit X.

What’s going on in Southern California journalism is sadly familiar — yet not hopeless. There is something new with this generation of journalism orphans. In the past, we downed shots and mourned as our publications died. Now, to paraphrase another literary luminary, Dylan Thomas, reporters are not going gentle into that good night.

Long Beach Post and Times staffers have publicly protested against their bosses. Knock L.A.’s banished writers and editors are shaming their former benefactors online. L.A. Taco is asking for money like an NPR host during a fund drive pounding nitro cold brew.

“We went public with our dire situation, because how can you expect help if you don’t ask for it?” said Cabral, 35, who I’ve known since he was a teenager with his own food blog. “Journalism for me has always been a fleeting career in flux that pulls the rug right under you when you start to get comfortable.”

I wish all of these folks well as they try to make it, including my colleagues at The Times, which has been unionized since 2018 and where we’ve worked for almost a year and a half without a contract. But even if we all fail, the dream to do good journalism in Los Angeles will never die. More publications are already rising.

The Los Angeles Public Press is barely a year old but is already making an impact with its coverage of the San Fernando Valley and Southeast L.A. County. Caló News, which focuses on Latino issues, will launch its own initiative to cover southeast L.A. County this summer. Newsletters run by individuals are filling in news holes and getting subscribers in the process. Hyperlocal publications like The Eastsider and This Side of Hoover are still informing readers about their communities.

Last month, I attended a forum at City Club LA hosted by the nonprofit Latino Media Collaborative, which sponsors Caló News, about what it deemed a “crisis” in Southern California journalism. Among the speakers were former La Opinión publisher Monica C. Lozano and California Community Foundation Chief Executive Miguel A. Santana. The conference room was packed with reporters young and old hoping to plug into the millions of dollars that local and national philanthropic organizations are planning to spend on L.A.-focused news operations in the coming years.

I wish them well, too — because someone has to succeed in this cursed industry, right? Right?

Business

L.A. bookseller went to protect his kids from a fight. He was shot and paralyzed

Luis Hernandez was worried about his children shortly before he was shot in the back outside his business near MacArthur Park.

Now the 40-year-old may never walk again.

On April 6, Hernandez and his wife were closing up their store where they sell Christian literature, keychains, backpacks and other items when a car parked next to his vehicle.

Moments earlier, he’d placed his three children — ages 2, 4 and 8 — into his car in the 700 block of South Alvarado Street as his wife locked up the store. It was shortly before 9 p.m. As he walked back to his car, an argument broke out between a person on the sidewalk and a group of people in the car parked next to him.

He wanted to move his car and children away from where people were arguing. As he got in the car, someone fired a gun from inside the gray Toyota Camry parked next to him, according to the Los Angeles Police Department.

He was shot in the back, and the Camry drove away, police said.

Hernandez was rushed to Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, where doctors explained to his family that the bullet had struck his spine and he was paralyzed from the waist down, according to Nora Flores, Hernandez’s cousin.

Luis Hernandez was shot in the back outside his business near MacArthur Park. Doctors say Hernandez is paralyzed from the waist down and no surgery will help.

(Courtesy of Nora Flores)

“They told us there was no other surgery they could do to reverse his condition,” Flores said. “We have faith that with physical therapy he can walk again. We’re trying to be very supportive.”

The people in the Camry are described as a man and woman and were last seen driving away, but there was no other information about the shooter or a motive, according to the LAPD.

“It just happened so fast,” said Hernandez’s wife, who does not want her name released because of safety concerns, as the suspects have not been identified.

Hernandez primarily works as a custodian and part-time at the store, which he opened about six years ago, according to Flores.

“He’s a very generous, kind person who is always willing to help. He’s a devoted father,” Flores said. “Whenever I see my cousin, I get happy, because his energy is always positive.”

Hernandez arrived in Los Angeles in 2007 from Tegucigalpa, Honduras. In his first two years in the United States, Hernandez lived with Flores’ family in L.A.

As a devout Christian, Hernandez volunteered most of his time at his church where he helped organize musical events and activities. He met his wife at church.

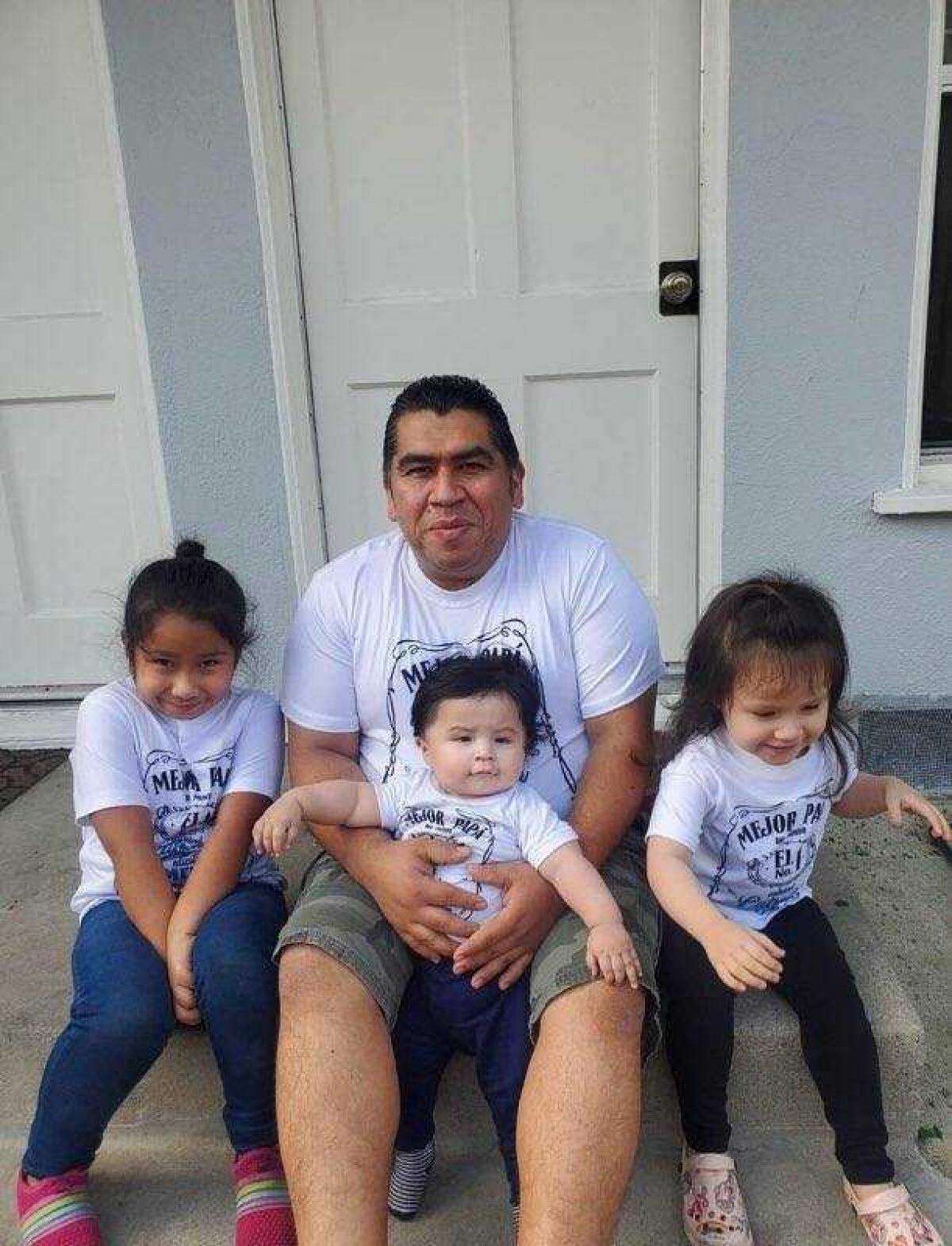

An undated photo of Hernandez with his three children, who were in the car with him when he was shot.

(Courtesy of Nora Flores)

Flores cannot understand why someone would shoot her cousin.

“He’s the furthest thing from someone who could be confused for a gang member,” she said.

She’s aware that Hernandez’s life is going to change forever. She set up a GoFundMe campaign to help pay for his medical expenses.

Hernandez is the sole provider in his family. They are trying to keep his spirits up, but he’s also trying his best to comfort his family.

“He’s telling us it’s going to be OK, he’s trying to assure the children,” his wife said.

Flores said: “I’m just thinking, of all the people in the world, why did this have to happen to him?”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Election Officials Continue To Face Violent Threats

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHope and anger in Gaza as talks to stop Israel’s war reconvene

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoSasquatch Sunset (2024) – Movie Review

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoThe Eclipse Across North America

-

Fitness1 week ago

This exercise has a huge effect on our health and longevity, but many of us ignore it

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoArizona Supreme Court rules that a near-total abortion ban from 1864 is enforceable

-

Uncategorized1 week ago

Uncategorized1 week agoANRABESS Women’s Casual Loose Sleeveless Jumpsuits Adjustbale Spaghetti Strap V Neck Harem Long Pants Overalls with Pockets

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoSponsored: Six Ways to Use Robinhood for Investing, Retirement Planning and More