Business

Unruly airplane passengers disrupting more flights, despite FAA’s zero-tolerance policy

With air travel recovering from the pandemic, a new study found that bad behavior among airline passengers has continued to rise.

A new analysis by the International Air Transport Assn. shows that unruly-passenger incidents on airplanes increased 47% from 2021 to 2022, from one incident per 835 flights to one incident per 568 flights.

Though incidents of physical abuse often draw the most attention, the most common types of incidents were “non-compliance, verbal abuse and intoxication,” according to the report. Other misdeeds included bringing outside alcoholic drinks into the cabin, failing to wear a seat belt and packing too much baggage.

Physical abuse incidents occurred on 1 in every 17,200 flights, a small fraction, but still an increase of 61% over the prior year. By comparison, the odds of a person being struck by lightning in their lifetime are 1 in 15,300, according to the National Weather Service.

The rise of incidents comes despite the Federal Aviation Administration issuing a zero-tolerance order in 2021 against unruly behavior. Instead of receiving warnings or being required to seek counseling, violators began to face criminal prosecution or fines of as much as $35,000. Airlines also have the authority to ban an unruly passenger from flying on their carrier in the future.

“Passengers and crew are entitled to a safe and hassle-free experience on board,” said IATA Deputy Director General Conrad Clifford. “While our professional crews are well trained to manage unruly passenger scenarios, there is no excuse for not following the instructions of the crew.”

The FAA said in April that it had sent 250 cases of unruly passengers to the FBI for potential criminal prosecution, including one in March, when a man tried to stab a flight attendant with a broken-off spoon.

FAA numbers showed that about two-thirds of unruly-passenger reports were related to face masks before April 2022, when a federal judge struck down masking requirements on planes and public transportation.

Incidents of passengers failing to comply with the flight crew, the most common category in 2022, were up 37% over 2021 and included smoking and vaping in lavatories, “failure to faster seat belts when instructed,” carrying on too much baggage or failing to store it, and consumption of outside alcohol on the plane, according to the IATA.

The data come from more than 20,000 reports submitted by some 40 airlines.

“No one wants to stop people having a good time when they go on holiday — but we all have a responsibility to behave with respect for other passengers and the crew,” said Clifford.

Business

Avian flu outbreak raises a disturbing question: Is our food system built on poop?

If it’s true that you are what you eat, then most beef-eating Americans consist of a smattering of poultry feathers, urine, feces, wood chips and chicken saliva, among other food items.

As epidemiologists scramble to figure out how dairy cows throughout the Midwest became infected with a strain of highly pathogenic avian flu — a disease that has decimated hundreds of millions of wild and farmed birds, as well as tens of thousands of mammals across the planet — they’re looking at a standard “recycling” practice employed by thousands of farmers across the country: The feeding of animal waste and parts to livestock raised for human consumption.

“It seems ghoulish, but it is a perfectly legal and common practice for chicken litter — the material that accumulates on the floor of chicken growing facilities — to be fed to cattle,” said Michael Hansen, a senior scientist with Consumers Union.

It is still unclear how the cows were infected — whether by contact with birds, or via feed made from litter waste — but litter has been associated with previous outbreaks of disease, including botulism.

Poultry litter causing the bovine cases of avian flu is considered “very unlikely, though not impossible” wrote Veronika Pfaeffle, in a joint statement from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration.

Poultry litter consists of manure, feathers, spilled feed and bedding material that accumulate on the floors of the buildings that house chickens and turkeys. It can contain disease-causing bacteria, viruses (including H5N1), antibiotics, toxic heavy metals, pesticides and even foreign objects such as dead rodents, birds, rocks, nails and glass.

It is typically mixed with hay or corn to make it palatable to livestock.

California bans the feeding of poultry litter to lactating dairy cows. However, it is legal to sell it as feed to beef and other cattle.

“It is a premium product used to help recycle waste into a sustainable product,” said Anja Raudabaugh, CEO of Western United Dairies. She said that although she could not make informed comments about its use outside of the state, “there is very little of it used here in California.”

California’s animal feed law — which applies to commercially sold feeds — requires that animal waste products sold for feed must contain no residues of pathogens, metals, pesticides or antibiotics.

The Department of Food and Agriculture’s Feed Program “inspects every California facility manufacturing dried poultry litter and reviews firms’ treatment verification records onsite,” said Steve Lyle, department spokesman.

However, it is unclear whether there are regulations addressing the private exchange or production of poultry litter or other animal waste for feed. Or how widespread the practice of feeding poultry waste to cattle is in the state or around the country.

It “was a common practice throughout the U.S. for many years,” said Lyle. “It is not a very common practice in California anymore.”

Chicken litter cannot be fed to lactating dairy cows under California law.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

According to Michael Payne, a researcher and outreach coordinator at the Western Institute of Food Safety and Security at UC Davis, there was at least one commercial processor of poultry litter in the state — Imperial Western Products, based in Coachella. That company was bought in 2022 by Arkansas’ Denali Water Solutions — which has had recent legal run-ins with environmental authorities in Missouri and Alabama over its handling of animal waste. It is unclear whether Imperial still produces feed from litter. An operator at the company directed calls to “corporate,” or Denali Water Solutions, which is owned by TPG Growth, a private equity firm. Denali did not provide comments for this story before publication.

The federal government does not regulate poultry litter in animal feed, and in many states — including Missouri, Alabama and Arkansas — there are no requirements or regulations regarding contamination or processing.

“The FDA may take regulatory action if it becomes aware of food safety concerns with poultry litter products intended for use in animal food in interstate commerce,” Pfaeffle said in the statement from both the USDA and FDA.

An online guide from the University of Missouri notes there are “no federal or Missouri regulations governing the use of poultry litter as a feed.” However, the guide’s authors urge users to employ “common sense.”

“Poultry litter should not be fed to dairy cattle or beef cattle less than 21 days before slaughter,” the guide notes, citing concerns about “residues of certain pharmaceuticals.”

Most other developed nations — including Canada, the United Kingdom and the countries within the European Union — have banned the practice. The FDA considered doing so in the U.S. in the mid-2000s.

For cattle farmers, the waste — which includes calcium, zinc and other minerals and vitamins — provides a cheap form of protein feed. For poultry farmers, the exchange allows them to divert the litter away from a landfill or from being burned.

In the 1980s, concerns about bovine spongiform encephalopathy — or mad cow disease — took hold across Europe, when cases of the incurable and invariably fatal neurodegenerative disease of cattle began to appear. The disease, which is caused by folded proteins known as prions, can transfer to people who eat the meat of infected cattle. In people, the disease is fatal and called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Just as cattle are fed poultry waste, chickens are often provided feeds that consist of cattle waste and renderings — creating a potential route for prions to re-enter the food supply. However, because the FDA mandates the removal of all tissues shown to carry the prions — such as brains and spinal cords — from poultry diets, the risk is reduced.

However, other more common pathogens are also found in poultry litter. In one 2019 study of litter used on farm fields as fertilizer, researchers found that every sample tested from U.S. broiler chickens carried E. coli strains resistant to more than seven antibiotics — including amoxicillin, ceftiofur, tetracycline, and sulfonamide.

It is unclear if the litter was heat treated before it was applied.

Raudabaugh said all poultry litter feed in California is kiln heated and exposed to temperatures that can kill bacteria, such as E. coli, and viruses, including H5N1.

“Firms are sampling and analyzing finished product for Salmonella regularly,” said Lyle, the state’s food and agriculture spokesman.

He noted that poultry is regularly tested for bird flu and that poultry waste from a flock infected with bird flu “cannot leave the premises until it has met CDFA requirements for ensuring the virus has been eliminated,” he said. “The premises is also tested and the quarantine is not released until the premises tests negative for highly pathogenic avian influenza.”

Lyle said cattle herds with “symptoms consistent” with bird flu infections “can be tested at the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory in consultation with the CDFA Animal Health Branch.”

He added that no symptomatic herds have been identified, “although one herd that lost pregnancies was tested and was negative” for the virus.

Business

Column: L.A.'s ultimate heartbreak industry isn’t Hollywood. It's local journalism

Whenever I think of the perilous state of local news, I think of Delicious Pizza in West Adams.

Great pizza! Small space, cool atmosphere. In the fall of 2017, I found myself there along with other journalism castoffs cursing the news gods.

I had just resigned as editor of OC Weekly after I refused to lay off half the staff. Daniel Hernandez was out of a job at VICE News after nearly four years there. Julia Wick had led the original LAist until its owner shut down the website because he claimed it wasn’t economically successful. Former LA Weekly editor-in-chief Mara Shalhoup was axed alongside most of her writers and editors after a new owner acquired the venerable alt-weekly.

Over beers and slices, we laughed and shared stories and fretted about the eternal erosion that is American journalism. None of us were about to give up on our beloved profession, though. There was talk of creating our own publication, but nothing serious. Instead, we hugged and went on to the rest of our lives.

Today, Mara is ProPublica’s South editor. Daniel edits The Times’ food section. Julia is on The Times’ 2024 election team. I’m a Times columnista, of course, frequently using Southern California’s past as a prism to understand what’s happening now and what might occur in the future.

And boy, does it not look good for local journalism — again.

Last month, the nonprofit Long Beach Post, which expertly covered the port city while the Press-Telegram atrophied, laid off nearly everyone. The publication’s board of directors maintained the move was necessary to save it from financial ruin — but former staffers insist it was retribution for their attempt to form a union.

Reporters for Knock LA, which focuses on social justice issues and law enforcement corruption, accused the publication’s sponsors, the leftist group Ground Game LA, of exiling them after they asked to spin off Knock into its own standalone entity.

For the record:

4:09 p.m. April 17, 2024An earlier version of this article said that Ground Game LA is the fiscal sponsor of Knock LA. Knock LA is part of Ground Game LA, and the two organizations share funding.

In the for-profit world, L.A. Taco, which centers food coverage while covering working class communities across Southern California, furloughed nearly everyone on its small team. Editor-in-chief Javier Cabral said they would be laid off if the publication isn’t able to hit 5,000 members by the end of April. (They were at 2,800 as of Monday). This follows the shuttering of one of California’s oldest continuously operating newspapers, the Santa Barbara News-Press, last year.

And, of course, there’s this paper. More than 100 of my colleagues were laid off last summer and earlier this year. Others took buyouts, and it seems recently that farewell emails from colleagues moving on to other jobs or retiring hit my mailbox daily.

It’s easy to portray what’s going on in local media as unprecedented and catastrophic, especially in the face of similar layoffs nationwide during an election year where accurate facts and nuanced coverage matter more than ever. But Southern California has always been an ossuary of failed publications done in by apathetic readership, clueless owners or a combination of both.

A 2006 rally at De La Guerra Plaza in front of the Santa Barbara News-Press newspaper’s offices. The newspaper, one of the oldest in California, ceased publishing last year.

(Michael A. Mariant / Associated Press)

Every generation in L.A. seems to suffer a journalism mass extinction event. In addition to what’s happening right now and what happened in 2017, there was the shuttering of two alt-weeklies, Los Angeles CityBeat and the Long Beach-based The District Weekly, at the turn of the aughts. I remember the demise of La Banda Elastica and Al Borde, two Spanish-language publications that focused on rock en español through the late 1990s and 2000s. Older folks will remember the end of the L.A. Herald Examiner in 1989, whose grandiose downtown headquarters are now used as a satellite campus by Arizona State University.

L.A.’s heartbreak industry isn’t Hollywood; it’s journalism. To paraphrase what the late A. Bartlett Giamatti said about baseball, it’s designed to break the hearts of those who work it.

You join the profession knowing that long hours, low pay and no respect from the public is the norm, yet you jump in anyway. You revel in your colleagues, your shared sense of mission and the stories you do — but then the reality of economics sets in, and you realize the good times won’t last. You wonder why readers don’t subscribe, why editors and publishers don’t innovate. You see co-workers lose their jobs or leave the profession — and then it’s your turn, one way or another.

It’s easy to armchair quarterback why publications fail. Blame technology, fragmented audiences, a lack of trust in news — it’s all of that, and more. But these conditions existed before photos appeared in newspapers, and will persist long after whatever Elon Musk inserts in our brains so we can’t quit X.

What’s going on in Southern California journalism is sadly familiar — yet not hopeless. There is something new with this generation of journalism orphans. In the past, we downed shots and mourned as our publications died. Now, to paraphrase another literary luminary, Dylan Thomas, reporters are not going gentle into that good night.

Long Beach Post and Times staffers have publicly protested against their bosses. Knock L.A.’s banished writers and editors are shaming their former benefactors online. L.A. Taco is asking for money like an NPR host during a fund drive pounding nitro cold brew.

“We went public with our dire situation, because how can you expect help if you don’t ask for it?” said Cabral, 35, who I’ve known since he was a teenager with his own food blog. “Journalism for me has always been a fleeting career in flux that pulls the rug right under you when you start to get comfortable.”

I wish all of these folks well as they try to make it, including my colleagues at The Times, which has been unionized since 2018 and where we’ve worked for almost a year and a half without a contract. But even if we all fail, the dream to do good journalism in Los Angeles will never die. More publications are already rising.

The Los Angeles Public Press is barely a year old but is already making an impact with its coverage of the San Fernando Valley and Southeast L.A. County. Caló News, which focuses on Latino issues, will launch its own initiative to cover southeast L.A. County this summer. Newsletters run by individuals are filling in news holes and getting subscribers in the process. Hyperlocal publications like The Eastsider and This Side of Hoover are still informing readers about their communities.

Last month, I attended a forum at City Club LA hosted by the nonprofit Latino Media Collaborative, which sponsors Caló News, about what it deemed a “crisis” in Southern California journalism. Among the speakers were former La Opinión publisher Monica C. Lozano and California Community Foundation Chief Executive Miguel A. Santana. The conference room was packed with reporters young and old hoping to plug into the millions of dollars that local and national philanthropic organizations are planning to spend on L.A.-focused news operations in the coming years.

I wish them well, too — because someone has to succeed in this cursed industry, right? Right?

Business

L.A. bookseller went to protect his kids from a fight. He was shot and paralyzed

Luis Hernandez was worried about his children shortly before he was shot in the back outside his business near MacArthur Park.

Now the 40-year-old may never walk again.

On April 6, Hernandez and his wife were closing up their store where they sell Christian literature, keychains, backpacks and other items when a car parked next to his vehicle.

Moments earlier, he’d placed his three children — ages 2, 4 and 8 — into his car in the 700 block of South Alvarado Street as his wife locked up the store. It was shortly before 9 p.m. As he walked back to his car, an argument broke out between a person on the sidewalk and a group of people in the car parked next to him.

He wanted to move his car and children away from where people were arguing. As he got in the car, someone fired a gun from inside the gray Toyota Camry parked next to him, according to the Los Angeles Police Department.

He was shot in the back, and the Camry drove away, police said.

Hernandez was rushed to Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, where doctors explained to his family that the bullet had struck his spine and he was paralyzed from the waist down, according to Nora Flores, Hernandez’s cousin.

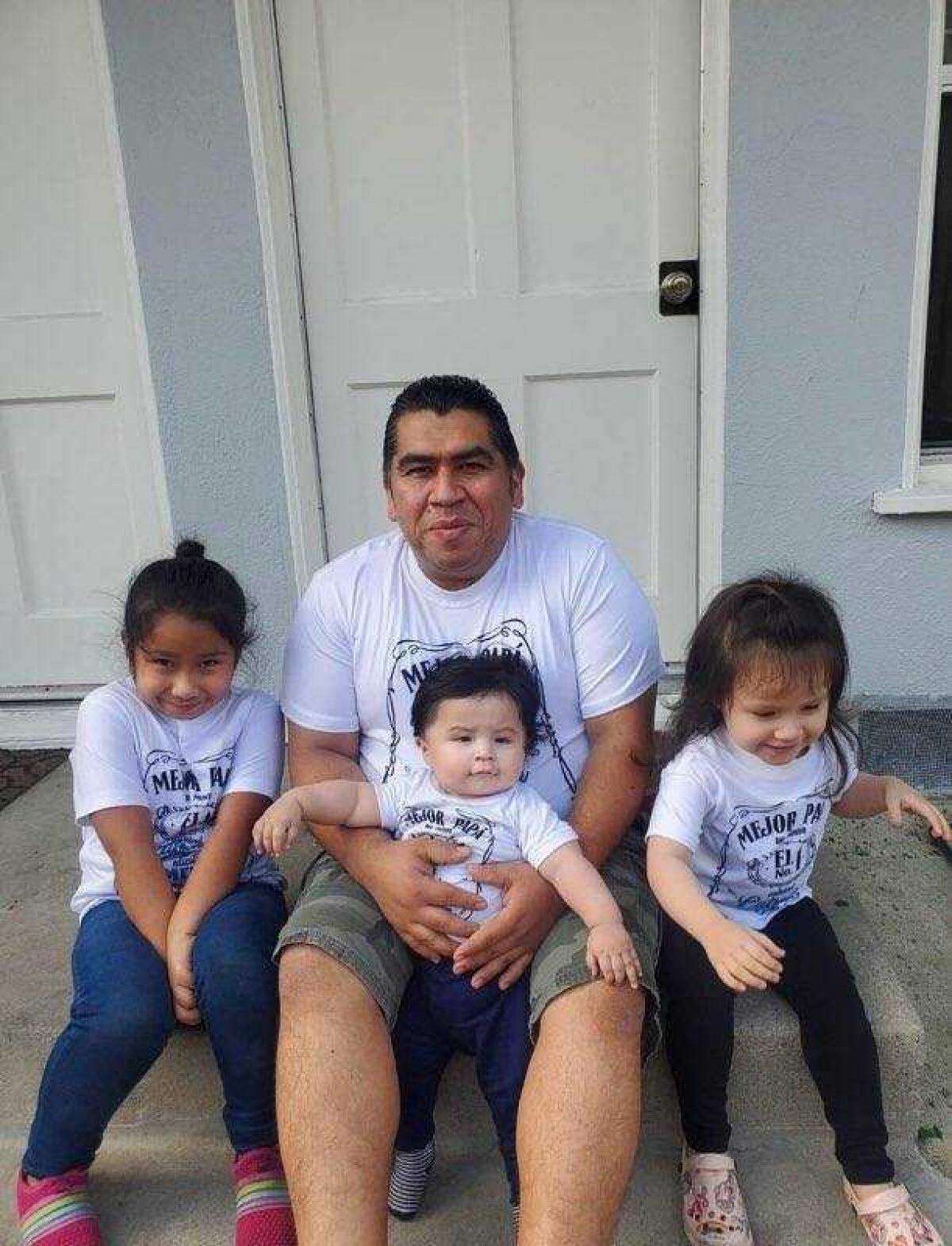

Luis Hernandez was shot in the back outside his business near MacArthur Park. Doctors say Hernandez is paralyzed from the waist down and no surgery will help.

(Courtesy of Nora Flores)

“They told us there was no other surgery they could do to reverse his condition,” Flores said. “We have faith that with physical therapy he can walk again. We’re trying to be very supportive.”

The people in the Camry are described as a man and woman and were last seen driving away, but there was no other information about the shooter or a motive, according to the LAPD.

“It just happened so fast,” said Hernandez’s wife, who does not want her name released because of safety concerns, as the suspects have not been identified.

Hernandez primarily works as a custodian and part-time at the store, which he opened about six years ago, according to Flores.

“He’s a very generous, kind person who is always willing to help. He’s a devoted father,” Flores said. “Whenever I see my cousin, I get happy, because his energy is always positive.”

Hernandez arrived in Los Angeles in 2007 from Tegucigalpa, Honduras. In his first two years in the United States, Hernandez lived with Flores’ family in L.A.

As a devout Christian, Hernandez volunteered most of his time at his church where he helped organize musical events and activities. He met his wife at church.

An undated photo of Hernandez with his three children, who were in the car with him when he was shot.

(Courtesy of Nora Flores)

Flores cannot understand why someone would shoot her cousin.

“He’s the furthest thing from someone who could be confused for a gang member,” she said.

She’s aware that Hernandez’s life is going to change forever. She set up a GoFundMe campaign to help pay for his medical expenses.

Hernandez is the sole provider in his family. They are trying to keep his spirits up, but he’s also trying his best to comfort his family.

“He’s telling us it’s going to be OK, he’s trying to assure the children,” his wife said.

Flores said: “I’m just thinking, of all the people in the world, why did this have to happen to him?”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Election Officials Continue To Face Violent Threats

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHope and anger in Gaza as talks to stop Israel’s war reconvene

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoSasquatch Sunset (2024) – Movie Review

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoThe Eclipse Across North America

-

Fitness1 week ago

This exercise has a huge effect on our health and longevity, but many of us ignore it

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoArizona Supreme Court rules that a near-total abortion ban from 1864 is enforceable

-

Uncategorized1 week ago

Uncategorized1 week agoANRABESS Women’s Casual Loose Sleeveless Jumpsuits Adjustbale Spaghetti Strap V Neck Harem Long Pants Overalls with Pockets

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoSponsored: Six Ways to Use Robinhood for Investing, Retirement Planning and More